Proposal (825) to South American

Classification Committee

Treat Sarkidiornis sylvicola as a separate species from Sarkidiornis melanotos

The American Comb-Duck, Sarkidiornis

sylvicola has been treated since the 19th century (including Hellmayr and

Peters [as Sarkidiornis carunculatus]) as a species apart from the

"African" Duck Sarkidiornis melanotos until Delacour &

Mayr (1945 Wilson Bull, 57: 3-55) treated as subspecies.

The reasons for this

subordination are as follows (Delacour & Mayr 1945: 28):

"The Comb Duck (Sarkidiornis melanotos)

includes two well-marked subspecies, one (melanotos) extending from

Africa to south-east Asia…, the other (carunculatus) inhabiting South

America. We have observed at Clères that the racial

hybrids are not intermediate. In such hybrid broods some birds look like pure melanotos

and others like pure carunculatus."

This subordination to

the Old World taxon was adopted by Meyer de Schauensee (1966. The species of

birds of South America), Blake (1977. Manual of Neotropical Birds), and the AOU

(1998. Check-list of North American Birds), but not by Wetmore (1965. The Birds

of the Republic of Panama), Kear (2005 Ducks, Geese and Swans), or Hoyo &

Collar (2014. HBW and BirdLife International Illustrated Checklist of the Birds

of the World).

In his phylogenetic

classification and a general listing of taxa, Livezey (1997. Annals of Carnegie

Museum 66 (4): 457-496) recognizes Sarkidiornis sylvicola as an

independent species emphasizing the contrasting coloring of the sides and

flanks, gray in S. melanotos and black in S. sylvicola.

The Delacour hybrids

were obtained (artificially?) in his particular zoo, in Clères,

Normandy, France. Generally, the

resulting hybrids have intermediate parental characteristics. I cannot comment on the meaning of

non-intermediate hybrids in BSC. However, this curious resilience of characters

seems to favor the independence of these phenotypes. Regardless, hybridization in captivity is not

a valid basis for considering two taxa to be conspecific under any modern version

of the BSC.

There may be other diagnostic

differences between sylvicola and melanotos. Apparently, sylvicola has smaller

dimensions in both sexes (at least, on average) than melanotos. The

calls (the species is basically mute) appear to be lower-pitched, with more

bass, in melanotos; however, the sampling (Xeno-canto) is very small.

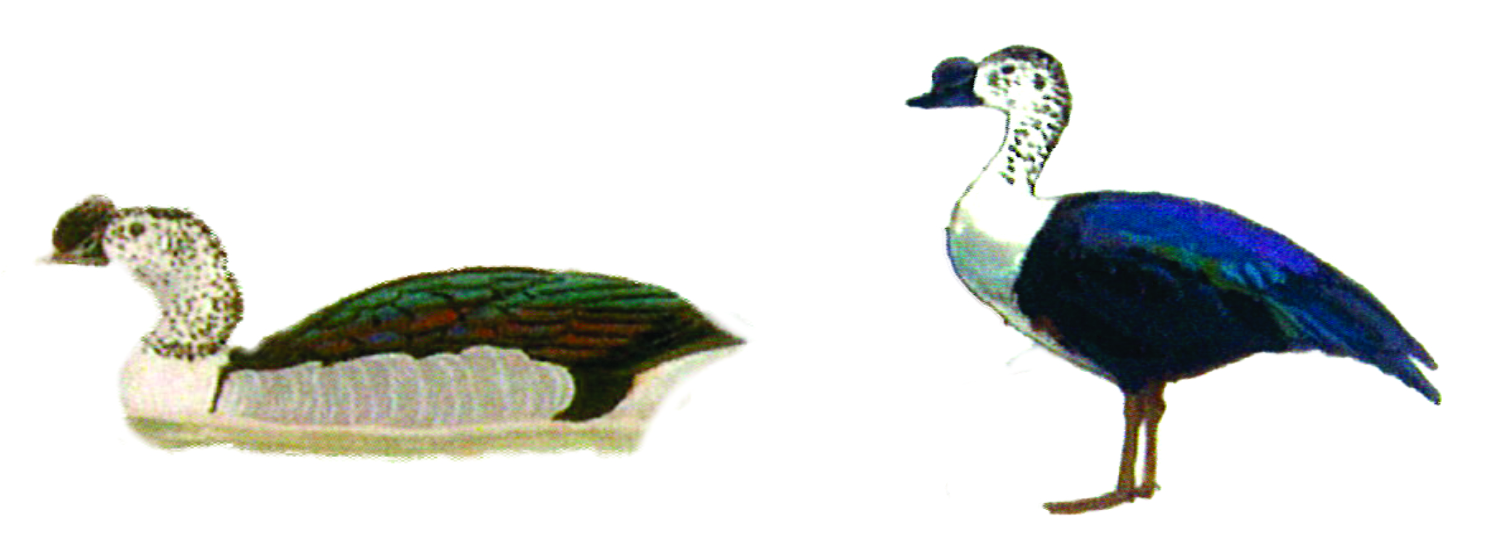

My vote is in support of

the split, considering the well-marked differences between these two. See

illustration below:

Fernando Pacheco, May

2019

Comments from Claramunt:

“YES. Tough

call. However, these birds are much more similar than what those illustrations

suggest. Check the illustrations in the HBW instead (see below). Basically, the main difference is black versus

grayish flanks. However, sylvicola

is also smaller, and del Hoyo & Collar (2014) mentioned the shape of the

comb, which seems slightly different, but a more detailed analysis would be

desirable.

“That

they hybridize in captivity is not evidence of potential free interbreeding in

the wild. The statement about hybrids being similar to one or the other parent

suggests that the main distinguishing character, the color of the flanks, is

produced by a single Mendelian gene. However, the differences between the two

taxa are not restricted to a single gene, as there are size differences. In

addition, flank color (and maybe comb shape) may be involved in sexual

selection and potentially species recognition. Taken together, I think that

elevating sylvicola to species is reasonable, pending some falsifying

evidence of reproductive compatibility or genomic homogeneity.”

sylvicola:

melanotos:

Comments

from Stiles: “YES; as noted by Santiago, the original reason for

lumping them was ill-founded.”

Comments

from Robbins:

“YES, for recognizing Sarkidiornis

sylvicola as a species based on the rather dramatic morphological

differences. As others have noted, captive hybridity is meaningless for

assessing species limits, especially with regard to waterfowl.”

Comments from Zimmer: “YES”. As noted in the Proposal,

and by the comments from others on the committee, hybridization in captivity,

particularly with a notoriously promiscuous group like waterfowl, is

meaningless in establishing species limits.

The plumage differences are fairly dramatic, and there are accompanying

mensural differences as well as likely differences in comb size and shape, all

of which trumps the flimsy basis for lumping these taxa in the first place, in

my opinion.”

Comments

from Jaramillo: “YES – Particularly as waterfowl are abnormally

uniform, not tending to show much geographic variation, other than in species

that have culturally mitigated migration routes (geese).”

Comments

from Remsen: “YES, but largely because the initial rationale for

the lump was based on nearly irrelevant captive breeding. By the way, this one is screaming out for a

genetic analysis not for classification but for estimating the age of the

split. These two really do not seem to

differ very much, phenotypically, thus suggesting a relatively recent split,

i.e. transoceanic dispersal. I wish we

had comparative information on displays and voice on which to evaluate this one

in terms of species rank.”