Proposal (829) to South American Classification Committee

Merge Oceanodroma into Hydrobates

Note from Remsen (May

2019): This proposal is a

spinoff of Shawn Billerman’s proposal to NACC, which

was passed unanimously. The proposal is

self-explanatory. The taxa that would be

affected in the SACC classification are as follows:

Oceanodroma

microsoma Least Storm-Petrel (NB)

Oceanodroma

tethys Wedge-rumped Storm-Petrel

Oceanodroma

castro Band-rumped Storm-Petrel

Oceanodroma

leucorhoa Leach's Storm-Petrel (NB)

Oceanodroma

markhami Markham's Storm-Petrel

Oceanodroma

hornbyi Ringed Storm-Petrel

Oceanodroma

melania Black Storm-Petrel (NB)

_________________________________________________________________________-

Merge the

storm-petrel genus Oceanodroma into Hydrobates

Background and New

Information:

The

northern storm-petrels, Hydrobatidae, are currently placed into two genera, Hydrobates and Oceanodroma. The genus Hydrobates

includes only a single species, the European Storm Petrel (Hydrobates pelagicus), whereas all other species of northern

storm-petrel are placed in the genus Oceanodroma.

Although there are still relatively few studies that look at the phylogenetic

relationships of the storm-petrels, recent work has shown that Oceanodroma is paraphyletic with respect

to Hydrobates, with the European

Storm-petrel embedded within the larger Oceanodroma

(Kennedy and Page 2002, Penhallurick and Wink 2004, Robertson et al. 2011, Wallace et al. 2017). Most studies have found

that the European Storm-Petrel is sister to Fork-tailed Storm-Petrel (O. furcata) (Robertson et al. 2011, Wallace et al. 2017; Fig. 1). As a result of the

paraphyly of Oceanodroma, most

taxonomic authorities (e.g.,

Dickinson and Remsen 2013) have merged the two genera, with Hydrobates Boie, 1822, having priority

over Oceanodroma Reichenbach, 1853.

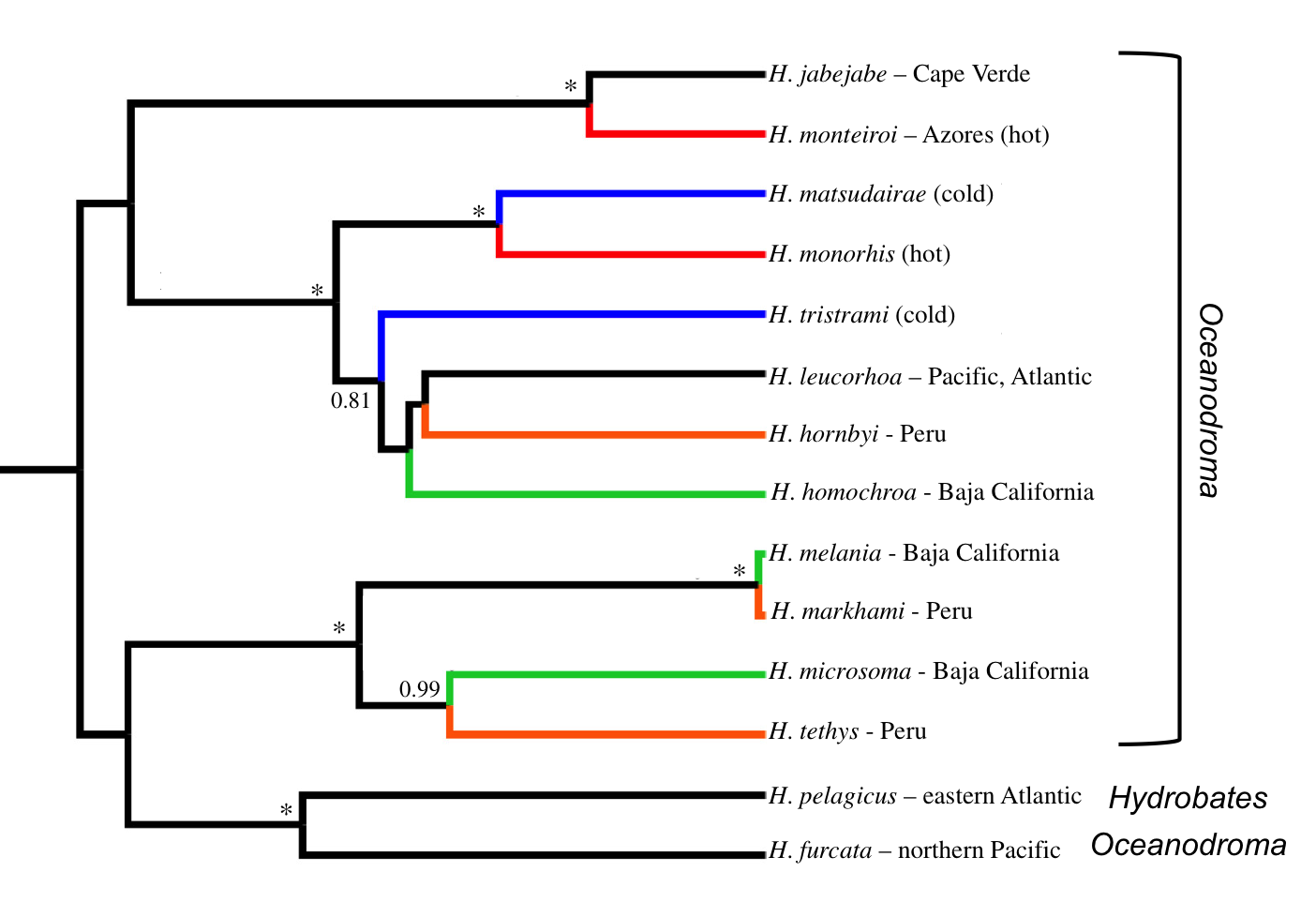

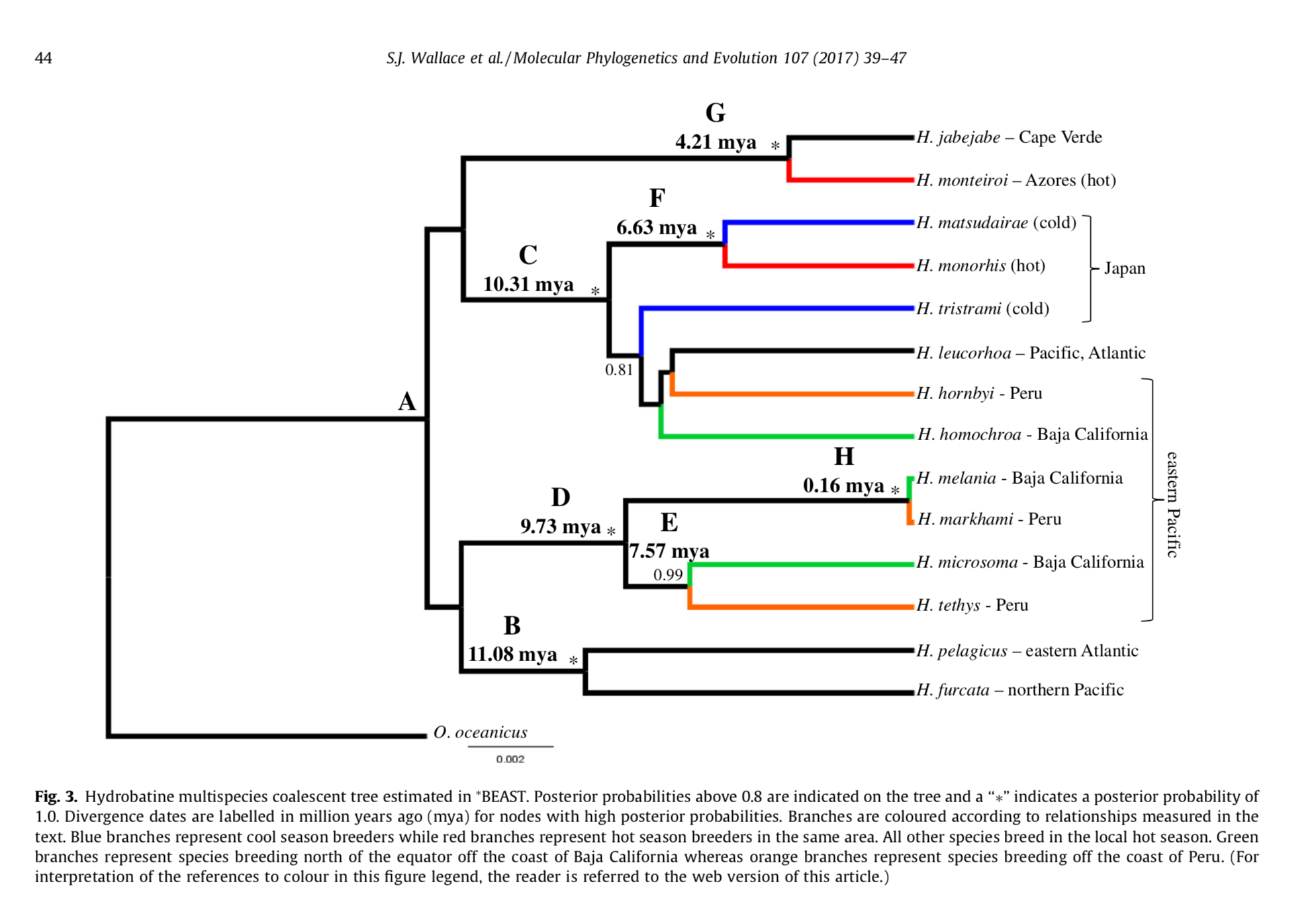

Figure 1. Bayesian phylogeny

(based on sequence data from cytochrome-b

and 5 nuclear introns), where ‘*’ indicates posterior probabilities of 1.0

and all posterior probabilities above 0.8 are given. Note that Hydrobates pelagicus is sister to Oceanodroma furcata, which is in turn

sister to a clade of New World Oceanodroma.

This larger clade is in turn sister to the rest of the Oceanodroma. Adapted from Wallace et al. 2017.

Although

the European Storm-Petrel is often found to be sister to Fork-tailed

Storm-Petrel, most other relationships within the family are not well resolved,

making it difficult to speculate on any well-supported clades within the family

(Robertson et al. 2011, Wallace et al. 2017).

Recommendation:

Based

on the findings of several recent molecular phylogenies (Penhallurick and Wink

2004, Robertson et al. 2011, Wallace et al. 2017), I recommend merging the

genus Oceanodroma with Hydrobates, given that Oceanodroma is paraphyletic with respect

to Hydrobates and that Hydrobates has priority. At this time, I

propose no change in the linear sequence of the family given the lack of

resolution of many relationships. This would result in the following changes to

the AOS Checklist:

European

Storm-Petrel (Hydrobates pelagicus)

Fork-tailed

Storm-Petrel (Hydrobates furcata)

Ringed

Storm-Petrel (Hydrobates hornbyi)

Swinhoe’s

Storm-Petrel (Hydrobates monorhis)

Leach’s

Storm-Petrel (Hydrobates leucorhoa)

Townsend’s

Storm-Petrel (Hydrobates socorroensis)

Ainley’s

Storm-Petrel (Hydrobates cheimomnestes)

Ashy

Storm-Petrel (Hydrobates homochroa)

Band-rumped

Storm-Petrel (Hydrobates castro)

Wedge-rumped

Storm-Petrel (Hydrobates tethys)

Black

Storm-Petrel (Hydrobates melania)

Guadalupe

Storm-Petrel (Hydrobates macrodactyla)

Markham’s

Storm-Petrel (Hydrobates markhami)

Tristram’s

Storm-Petrel (Hydrobates tristrami)

Least

Storm-Petrel (Hydrobates microsoma)

References

Kennedy, M., and R.D.M.

Page. 2002. Seabird supertrees: combining partial estimates of Procellariiform

phylogeny. The Auk, 119: 88-108.

Penhallurick, J., and

M. Wink. 2004. Analysis of the taxonomy and nomenclature of the

Procellariiformes based on complete nucleotide sequences of the mitochondrial

cytochrome b gene. Emu, 104:125-147.

Robertson, B.C., B.M.

Stephenson, and S.J. Goldstien. 2011. When

rediscovery is not enough: taxonomic uncertainty hinders conservation of a

critically endangered bird. Molecular

Phylogenetics and Evolution, 61: 949-952 .

Wallace, W.J., J.A.

Morris-Pocock, J. González-Solís, P. Quillfeldt, and

V.L. Friesen. 2017. A phylogenetic test of sympatric speciation in the Hydrobatinae

(Aves: Procellariiformes). Molecular

Phylogenetics and Evolution, 107:39-47.

Submitted by: Shawn M. Billerman

Date of Proposal: 3 December 2018

Comments from Jaramillo: NO. This is what I sent NACC on

this proposal:

“Dear

committee members, I wanted to reach out and make sure you were aware of a

potential issue in the data brought forward in the current proposal: Merge the

storm-petrel genus Oceanodroma into Hydrobates. The issue has to do with the

placement of markhami (Markham’s

Storm-Petrel) as sister to, and essentially equivalent to Black Storm-Petrel (melania) in Wallace et al. 2017 (Molecular

Phylogenetics and Evolution, 107:39-47). In Table 2 you will see that the

divergence between these two species is very small, with “0” being included in

the range of divergence possibilities. The problem is that in reality,

biologically, and in every way other than both being storm-petrels and all

dark, the two are very different. This is an incredibly surprising result!! I am

quite sure that the reason for this is that the Peruvian specimen of markhami that is used (noted as soft

tissue in Table 1) is actually a non-breeding melania. Oceanodroma melania

is very common in Peruvian waters and recently field observers have noted that

they can be more common than markhami

there. This is recent information that is available due to good digital photos,

historically it was assumed that markhami

was the “default” large dark storm petrel in those waters. I noted this

potential error to Vicki Friesen, she replied with this note:

‘As I’m sure you know, Markham’s storm-petrels are (or

were) hard to sample, hence the use of a museum specimen. This specimen came

from the Academy of Natural Sciences in Philadelphia (specimen number 11751).

We didn’t actually see it, but trusted the expertise of the biologists and

curators who collected and preserved it. We would definitely be interested in

re-visiting the systematics of this species (and any others represented only

toe pads in our study) if new samples could be collected. Thank you for

contacting us. – Vicki’

“As

it stands it is likely that no genetic information exists for markhami, and its relationships are

therefore still unclear. I am willing to bet that it will be in the group that

it most closely resembles in flight style, coloration etc, which is with Clade

B, the one that includes leucorrhoa.

If future proposals consider re-arranging the sequence of the storm petrels,

and I think there is ample reason to do so with available data, do take into

consideration that markhami is almost

certainly not closely related to melania.

“Finally,

I ask you to consider that merging the entire family into one genus creates a

rather uninformative genus! Some of these nodes are thought to be over 11 mya,

and there are some clear and well-defined clades within the family. I would

suggest that it would be better to separate them out into 4-5 genera to better

represent and segment the diversity within the family. For example, the Halocyptena genus (melania, tethys, microsoma) shares a distribution in the

Eastern Pacific, they also have particularly long tarsi for northern storm

petrels, as well as very dark chocolate colored plumage lacking the gray tones

(when fresh) of other all dark storm-petrels. Note that white in the rump is

not an informative character for storm petrels. The pale ulnar bar on these

species is restricted to the greater coverts, while on typical Oceanodroma the ulnar bar extends to the

bend of the wing and on to the distal median and lesser coverts. The very long

legs of melania, was distinctive

enough that previously it was classified in its own genus (Loomelania), I think that Halocyptena

predates it for the group name, however. I would predict that once other

details such as voice can be added to the dataset, the cohesiveness of this

genus will become even more clear cut. Similarly, the Band-rumped storm-petrels

would make a good genus, one that has a wide distribution in the northern

hemisphere and probably contains more species than currently understood. The

main clade would remain as Oceanodroma,

and I would provisionally include markhami

in there. Finally, the more contentious issue would be if one lumps but furcata and pelagicus in one genus (Hydrobates)

or a different genus is chosen for furcata.

The two are a clade but they are not particularly closely related. In any case,

this multi-genus organization would make for a much more informative way to

subdivide the family. Creating a one genus family, for a group which is both

highly widespread in distribution and holds relatively old lineages does not

make much sense.

Comments

from Stiles:

“NO, as it stands. If branch lengths are any indication of lineage ages, there

are two genus-level groupings here: the group from melania through furcata (perhaps excluding markhami as stated by Alvaro), and the

“other Oceanodroma” (jabejabe through homochroa). The former group would be Hydrobates. Because the type species of Oceanodroma is furcata,

another name would be needed for the latter; Cymochorea Coues 1864, type species leucorhoa, seems the most likely name.”

Comments

from Robbins:

“NO, based on comments by both Alvaro and Gary.”

Comments

from Remsen:

“NO. In a reversal of my vote and comments in NACC, which were flawed because I

did not consult the original paper, which has a figure not presented in the

proposal:

“This shows that regardless of

resolution within clades, genetic support is strong for recognition of four

clades as genera, all of which are predicted to be evolving separately since

the Miocene, i.e. older than most groups we label as genera. The importance of treating them as genera is

to emphasize the morphological conservatism in this group relative to other

avian lineages, and thus emphasize one of the most important features of

storm-petrel evolution. One problem with

this is that “markhami” is actually a melania sample, as

indicated in Alvaro’s comments (yet another example of why double-checking ID

of vouchers is important!). Thus,

placement of markhami would be based on educated guesswork. Another problem is that a new genus would

need to be named for extralimital monteiroi-jabejabe

(“not our problem”); tentative inclusion in Clade C would be the solution

NACC could follow. However, I prefer

sorting out the markhami problem than obscuring 10 my-old diversity in

one broad genus. For what it’s worth,

Mathews named four additional genera in the group, including Loomelania, which was still used by AOU

(1957). A new proposal recognizing

multiple genera would need to sort out the nomenclature carefully.”

Comments from Claramunt: “YES. The molecular data is robust and I don’t see any

way of subdividing this family into clear and logical genus-level taxa. It is

also premature to base any subdivision on divergence times; the same paper

presents much younger estimates as plausible alternatives. Subdividing these

storm petrels into multiple genera will not only create a discrepancy with NACC

but also, I think, will produce confusion and frustration among users of the

classification. Maybe in the future we can consider a proposal for subdividing

this family, but at this point, the only option is to lump Oceanodroma into Hydrobates. Otherwise, for how long will we be maintaining a

paraphyletic

Oceanodroma?”

Additional comments from Remsen:

“YES, reversing my vote, based on Santiago’s comments, which actually reflect

the comments of most NACC members. Until

all the details are sorted out, including a thorough investigation of the

backbone nomenclature, I prefer maintaining a single broad genus rather than

trying to do an adequate job re-arranging generic limits within the context of

a SACC proposal. Looking forward to a

publication that does this properly.”

Comments from Schulenberg: “Hydrobates (the older name) apparently is embedded in Oceanodroma.

One solution is to recognize a single

genus (Hydrobates) for all (e.g., Dickinson and Remsen 2103, del Hoyo

and Collar 2014, NACC, my own preference), or one can opt to partition these

species into multiple genera (from two up to perhaps six genera).

“One suggestion I have is anyone who votes NO on the single genus

solution ought to specify exactly what they see as the desirable number of

genera to recognize.

“More importantly, SACC should recognize that accepting putting

some species into Hydrobates while retaining others in Oceanodroma

is not a option that is on the table. the type

species of Oceanodroma is furcata, which apparently is sister to Hydrobates

- so Oceanodroma disappears no matter what.

“At some point the nomenclatural experts will need to be

consulted. my take - and I don't bill myself as a nomenclatural expert - is

that the most likely options (based on Figure 3 in Wallace et al. 2017 - I

haven't checked other relevant papers) - include:

“two genera:

Hydrobates: pelagicus, furcatus,

tethys, melania, microsoma

Cymochorea Coues 1864, type leucorhoa:

hornbyi, leucorrhoa, socorroensis, cheimomnestes, monorhis,

homochroa, castro, monteiroi, jabejabe,

matsudairae, tristrami

Hydrobates in turn could be

split into two genera:

Hydrobates: pelagicus, furcatus

Halocyptena Coues 1864, type microsoma:

tethys, melania, microsoma

or into three

genera:

Hydrobates: pelagicus, furcatus

Halocyptena: tethys, microsoma

Loomelania Mathews 1934, type melania:

melania

and Cymochorea also could be split

into two genera:

Cymochorea: hornbyi, leucorrhoa, socorroensis,

cheimomnestes, monorhis, homochroa, matsudairae, tristrami

Thalobata Matthews 1943, type species castro:

castro, monteiroi, jabejabe

“or three genera

Cymochorea: hornbyi, leucorrhoa,

socorroensis, cheimomnestes, homochroa, tristrami

Thalobata: castro, monteiroi,

jabejabe

Pacificodroma Bianchi 1913, type

species monorhis: monorhis, matsudairae

“or, again, there's nothing wrong with classifying all in Hydrobates

and walking away.”

Additional

comments from Robbins:

“After reviewing this again following Tom's comments,

I feel at a minimum two genera should be recognized because of the very deep

split, i.e., Hydrobates and Cymochorea. Obviously, if one wants to atomize things, one

could recognize 4 or even 6 (why go that far as it starts to become meaningless

to communicate relationships).

What should be considered regarding

Tom's suggestion of recognizing a single genus vs multiple genera is how is the

timing of the various branches of this clade compared to other currently

recognized seabird genera? That is we

should attempt to be consistent in what we call a genus if time is considered a

parameter in defining genera.”

Additional

comments from Claramunt: “I don’t think that even a two-genera solution is

warranted for two important reasons:

“1) We don’t know the basal split. The base of

the tree is, essentially, a polytomy. There is no statistical support for the

basal relationships that are resolved in some of the trees.

“2) We don’t know how old the genus

is. Wallace et al. estimates range from 5 to 22 million years. In addition, it

is obvious that the evolutionary clock is ticking slower in these petrels, so

the use of the absolute age is not completely justified as a yardstick.”

Comments

from Pacheco:

“YES. Because NACC has adopted the single-genus

treatment in agreement with Santiago’s comments, the reasons for arrangement in

two or more genera become less obvious.”

Comments

from Stotz:

“YES. This might not be the best answer,

but I think it is the only approach we can currently justify.”

Comments

from Bonaccorso:

“YES. At least for now. Even if the basal split lacks

support. Naming four genera without solving sampling issues would generate more

instability.”

Comments

from Areta:

“NO. I agree with Alvaro and with Van´s first comments. Having a single-genus

family including multiple species (limits of which are in need of further

study) with fairly deep divergence times makes no sense to me: it hides

whatever is shared by species groups and does not facilitate meaningful

communication, nor helps condense what is known of these birds (two important

features of any classification). This proposal has no analysis or suggestion of

other alternatives, and no attempt at all to put biological or morphological

data in the game, as such, it is an unbalanced view whose outcome will most

likely be the merging of everything under a single genus. Voting NO is

uncomfortable because it leaves a paraphyletic Oceanodroma, but I see no reasonable and solid alternative

proposed.

“I

am in no position to propose in how many genera the family Hydrobatidae could

be reasonably split because a) it is a daunting work that should be done with

deep biological knowledge of the birds, b) it demands careful examination of

nomenclatural facts, c) there are more taxa that need to be sampled, and d) it

should be published as a review paper dealing with the pros and cons of

different classification schemes. Recently, Howell & Zufelt (2019) used a

three genera approach with Thalobata,

Halocyptena and Hydrobates (I thank Quillén Vidoz for sharing images of this book).

“Regarding

stability, lumping everything in no way serves stability better than other

alternatives. It just sweeps complexity (and knowledge) under the carpet. To be

sure, yes, a single Hydrobates genus

including all species is consistent with phylogenetic information. But is this

useful?

“I

am seeing that several molecular phylogenetic works lead to proposals that

favor the creation of large genera. However, these proposals seldom attempt to

analyze uniting features of smaller units that could be reasonably separated at

the genus level (a largely subjective decision, we know). In my view,

classifications should integrate these data into a useful research and

communication device, and my take is that just looking at trees without

understanding the birds will not produce the best possible classification.

Maybe the single-genus option is informative enough and other options do not

add anything meaningful, but Alvaro´s comments, Howell & Zufelt ´s 2019

book and the level of genetic differentiation suggest that there are several

features to be uncovered to subdivide Hydrobatidae into genera. Indeed, looking

at the original descriptions of those old names would be an excellent starting

point. But this should be done comparatively, integrating modern evidence,

etc., and not by me in a vote on a proposal. I am sure that Steve Howell can

contribute loads of ideas and information here. The tension between the recognition

of multiple smallish genera and single large genera needs to be sorted out

based on integrative evidence. I do not see such an integration here, and so I

feel uncomfortable with the proposal and with the options debated so far.

“Howell,

S.N.G. & Zufelt K (2019) Oceanic birds of the World. Princeton University

Press, NJ.”

Comments

from Zimmer:

“YES. I’m in

broad agreement with Alvaro and others that lumping everything into Hydrobates

would mask some pretty deep divisions, and that there are some pretty

significant biological/ecological/biogeographical (and, almost certainly vocal)

distinctions between these storm-petrels that are worthy of recognition at the

generic level. However, I think that any

such novel classification needs its own separate proposal, and that proposal

needs to be based upon some published analysis that integrates multiple data

sets (i.e. not just the genetic data). Meanwhile,

I think it is far preferable to recognize a single, overly broad genus that at

least is monophyletic, rather than continue with a classification that also

conceals considerable variation, while also being demonstrably paraphyletic.”

Additional

comments from Stiles:

“I change to YES to sinking Oceanodroma into Hydrobates

… if only to preserve monophyly. Hopefully someone like Alvaro can get

together with a genetics lab and resolve the basal polytomy and incorporate

data on plumage, flight, and vocalizations to get a good robust phylogeny!”