Proposal (830) to South American

Classification Committee

Transfer Picoides fumigatus and all Veniliornis to Dryobates

Note from Remsen (May 2019): This proposal is a spinoff of Shawn Billerman’s proposal

to NACC, included below. NACC (Chesser

et al. 2018) went with the second option, namely an expanded Dryobates. The taxa that would be affected in the SACC

classification is Picoides fumigatus

and all Veniliornis. Below is a version of my synopsis for SACC

for why an expanded Dryobates is the

best option.

New phylogenetic data require either the resurrection of Leuconotopicus or dramatic expansion of Dryobates Boie 1826. I favor the latter. This entire group shares many plumage and

vocal characters. Replace the browns of Veniliornis

with blacker plumage and you repeat many of the plumage patterns and vocal

characters of northern species in this group (Clade 4 in the figure below). Furthermore, fumigatus masqueraded as a Veniliornis

for its entire taxonomic history, because it was brown and tropical, until DNA

sequence data revealed that it was a "Picoides". That Leuconotopicus

fumigatus was never suspected of

being anything but a Veniliornis

tells you all you need to know about phenotypic similarity in this group. At a more familiar level to non-South

Americans, extra-limital Hairy Woodpecker would be in Leuconotopicus, whereas Downy Woodpecker would be in Dryobates s.s. Although plumage

mimicry is likely involved in driving some of the similarity between these two

(just as in Campephilus and Dryocopus), no one ever suspected that

they Hairy and Downy were not congeners based on overall plumage and vocal

characters (in contrast to Campephilus

and Dryocopus).

Phenotypic considerations aside, what seals the deal for me

is the time-calibrated phylogeny of Shakya et al., which predicts that this

radiation is just 7 million years old, i.e. well within the age boundaries associated

with taxa treated at the rank of genus, including widely recognized genera in

the same Shakya et al. tree. In fact,

the node that would define Dryobates s.l.

would be only slightly older than the nodes that define the other two genera in

the group, Dendrocopos and Dendropicos, neither of which contain

groups treated as separate genera and both of which contain internal nodes

older than those that define the 3 proposed genera.

Because classification at this level is to some degree subjective,

I find it more useful to recognize a single genus that has speciated

extensively and that shares many characters among component species than to

recognize three genera, the composition of one of which (Leuconotopicus) doesn't seem to make much "sense", at

least initially (e.g. borealis, fumigatus, and villosus in same genus).

Recommendation: I recommend a YES on

this, to follow NACC and Billerman’s option 2 below.

Van Remsen, May 2019

_________________________________________________________________________-

Revise generic

assignments of woodpeckers of the genus Picoides

Background:

Based

largely on the phylogeny of the pied woodpeckers from Fuchs and Pons (2015), as

well as the findings of Weibel and Moore (2002a, 2002b) and Winkler et al. (2014), Proposal 2016-A-4

proposed that the genus Picoides be

split into three genera (Picoides,

Dryobates, and Leuconotopicus).

This proposal did not pass, with most “no” votes opting to wait for additional

studies, several of which were known to be in the works.

The

following species were included in 2016-A-4 and are considered in this

proposal:

Picoides scalaris

Picoides nuttallii

Picoides pubescens

Picoides fumigatus

Picoides villosus

Picoides arizonae

Picoides stricklandi

Picoides borealis

Picoides albolarvatus

Picoides dorsalis

Picoides arcticus

New Information:

Two

papers that support the findings of Fuchs and Pons (2015) were recently

published: a supertree of the family Picidae (Dufort 2016) and a comprehensive

phylogeny of 203 of the 217 species of woodpeckers based on 6 genes (3 mtDNA

loci, one Z-linked gene, and 2 autosomal loci; Shakya et al. 2017). Both studies largely corroborate the results of Fuchs

and Pons (2015), supporting the finding that the Picoides of North America are paraphyletic and should be split into

3 genera.

Addressing

some of the concerns of the committee from 2016, these studies (1) place the

pied woodpeckers sampled by Fuchs and Pons (2015) into a broader context of

other members of Picidae (notably sampling additional species of Veniliornis, which largely renders two

large clades of Picoides paraphyletic);

and (2) sample additional loci, providing greater confidence for important

nodes relevant to the revision of

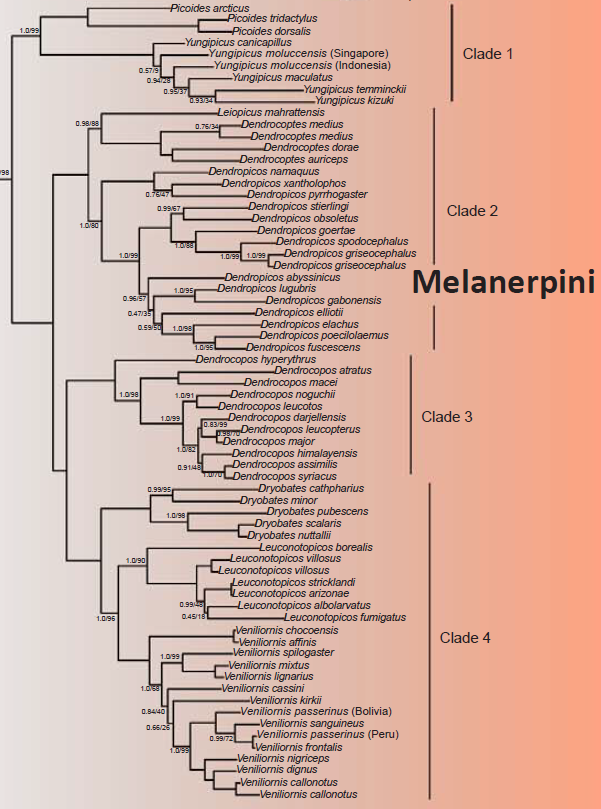

Figure 1: Part of Fig. 1 from Shakya et al. (2017), showing the relevant

subset of their phylogeny. This is a Bayesian tree based on mtDNA and nuclear

sequence data. Posterior probabilities less than 1.0 and bootstrap values less

than 100% are shown next to nodes. Nodes without values have posterior

probabilities of 1.0 and bootstrap values of 100%.

Picoides. Species of Picoides in the current NACC classification form 3 clades in all

recent phylogenies (Fig. 1; Fuchs and Pons 2015, Dunfort 2016, Shakya et al. 2017). The “three-toed”

woodpeckers (P. dorsalis and P. arcticus) are sister to a clade of

Asian woodpeckers previously in the genus Dendrocopos

(Yungipicus in Shakya et al. 2017). These two clades are in

turn sister to the remaining species of Dendrocopos,

Picoides, Veniliornis, and Dendropicos.

In Shakya et al. 2017, this

relationship received very high support, whereas Dufort 2016 found high to

moderate support for this relationship. The other North American species of Picoides are further split between two

clades, which are not sisters. Instead, fumigatus,

villosus, arizonae, stricklandi, borealis,

and albolarvatus form a

well-supported clade, which is sister to a large and well-supported clade of Veniliornis (represented on the North

American checklist only by V. kirkii).

These two well-supported clades are in turn sister to the remaining North

American species of Picoides (pubescens, nuttallii, and scalaris), which form a clade that also

includes two Eurasian species of Dendrocopos

(minor and cathpharius).

Recommendation:

(1)

Based on these well-supported molecular phylogenies of the Picoides, I recommend following the taxonomic suggestions of Fuchs

and Pons (2015), which were also followed by the two more recent woodpecker

studies (Dufort 2016, Shakya et al.

2017). This included resurrecting two genera, Leuconotopicus and Dryobates.

Under this new classification, Dryobates

would include pubescens, nuttallii,

and scalaris, whereas Leuconotopicus would include fumigatus, villosus, arizonae, stricklandi, borealis, and albolarvatus. Both arcticus

and dorsalis would be retained in Picoides. Adopting these changes would

also require revision to the linear sequence on the checklist. I propose the

following linear sequence:

Sphyrapicus

Xiphidiopicus

Picoides arcticus

Picoides dorsalis

Dendrocopos major

Dryobates pubescens

Dryobates scalaris

Dryobates nuttallii

Leuconotopicus borealis

Leuconotopicus villosus

Leuconotopicus arizonae

Leuconotopicus stricklandi

Leuconotopicus albolarvatus

Leuconotopicus fumigatus

Veniliornis kirkii

(2)

A second option for revising the generic limits of Picoides is available but not recommended. Under this option, arcticus and dorsalis would again be the only species of Picoides in North America, but all other members would be included

in an expanded Dryobates, which would

include pubescens/scalaris/nuttallii, all

of Veniliornis, and all the members

of the borealis/villosus/arizonae/stricklandi/albolarvatus/fumigatus

clade. The genus Dryobates 1826

has priority over Veniliornis 1854

and Leuconotopicus 1845. This

arrangement would eliminate the need for multiple genera of morphologically

similar species. The linear sequence would be the same as the one shown above,

except Dryobates would replace Leuconotopicus and Veniliornis.

Literature

Cited:

Dufort, M. J.

(2016). An augmented supermatrix phylogeny of the avian family Picidae reveals

uncertainty deep in the family tree. Molecular

Phylogenetics and Evolution, 94:

313-326

Fuchs, J. and J.

M. Pons (2015). A new classification of the pied woodpeckers assemblage

(Dendropicini: Picidae) based on a comprehensive multi-locus phylogeny. Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution, 88: 28-37

Shakya, S. B., J.

Fuchs, J Pons, and F. H. Sheldon (2017). Tapping the woodpecker tree for

evolutionary insight. Molecular

Phylogenetics and Evolution, 116:

182-191

Weibel, A. C. and

W. S. Moore (2002a). Molecular phylogeny of a cosmopolitan group of woodpeckers

(genus Picoides) based on COI and cyt

b mitochondrial gene sequences. Molecular

Phylogenetics and Evolution, 22:

65-75

Weibel, A. C. and

W. S. Moore (2002b). A test of a mitochondrial gene-based phylogeny of

woodpeckers (genus Picoides) using an

independent nuclear gene, β-fibrinogen intron 7. Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution, 22: 247-257

Winkler, H., A.

Gamauf, F. Nittinger, and E. Haring (2014). Relationships of Old World

woodpeckers (Aves: Picidae) – new insights and taxonomic implications. Annalen des Naturhistorischen Museums in

Wien B, 116: 69-86

Submitted by: Shawn M.

Billerman

Date of Proposal: 16 January 2018

Comments

from Stiles: “YES, to option 2 all three clades in Dryobates (to maintain relatively

similar genus ages in at least this part of Picidae).”

Comments from Claramunt: “YES. It will be traumatic for many of us to abandon

the traditional Veniliornis

for so many species but, at the end,

I think that it is the best solution; better than dealing with what seem to be

arbitrary divisions from an phenotypic standpoint, or the pain of using “Leuconotopicus.”

A large genus of small woodpeckers, so be it. As far as I can see, this lumping

will not incur in any problem of homonymy.”

Comments from Pacheco:

“YES. Following that

adopted by the NACC.”

Comments from Zimmer: “YES” (with a big gulp!) to Option 2, which, although “traumatic” as

Santiago suggests, is still more palatable to me than Option 1, for all of the

reasons stated by Van.”

Comments

from Jaramillo:

“NO – This group is difficult to deal with morphologically due to both possible

mimicry and convergence, as well as coloration that correlates with

tropical/temperate differences in tree bark color and darkness. As such, each

one of the clades is nearly impossible to adequately categorize. It is a unique

situation given the oddities of what affects plumage coloration in this group.

As such, I would give the genetic clades a higher degree of importance in

making the judgement of separating these groups, which are seemingly

undefinable! In essence the tools we usually use are not available to us, and

there is what appears to be a mismatch between morphology and clade. So, I am

inclined to separate them based on the genetic clade rather than lump them all

into a huge big mess that is no more informative than the smaller groups that each

deserve a genus name.”

Comments

from Areta:

“NO, i.e. yes to option 1. I am very

uncomfortable with merging everything in Dryobates, which makes the

genus a large dumping bag. Biogeographically, Dryobates is an Holarctic

genus, Leuconotopicus

is essentially a Mesoamerican/North American clade with a single species (fumigatus,

very different from all Veniliornis!) extending into South America, while Veniliornis

is essentially a South American clade. Anyone could take those study units and

make fruitful comparative research. This improved three-genera level taxonomy

should help further studies in search of common patterns and to uncover shared

traits that have remained undiscovered.

“Endorsing

the lumping of genera under a massive genus in the XXI Century is difficult to

swallow for me, especially when no attempts have been made to find common

themes in members of each grouping (i.e., Dryobates, Leuconotopicus

and Veniliornis).

The same happened before with the Hydropsalis proposal, and we

finally retained several genera instead of a massive Hydropsalis based on their

shared traits. In sum, merging everything in Dryobates may seem comfortable,

but seems to be comfortable only because no attempt has been made to

characterize or understand its underlying clades.”

“Finally, in the name of stability,

keeping usage of Veniliornis

for South American taxa is desirable. I find the three genera solution (two of

which would occur in South America) the best one by far.”

Comments

from Bonaccorso:

“YES. Although I am quite

reluctant given the arguments by Nacho (I do really like biogeographically

consistent clades) and, like Santiago, I will hate to lose Veniliornis,

absence of clear diagnostic morphological characters make it difficult to

justify three different genera. In a more practical issue, although not the

most important point is that if NACC already adopted this merge, we will create

a great lot of confusion for people that is not well aware of these two

different "ways" of classifying birds.”

Additional comments from

Remsen: “Concerning the loss

of Veniliornis mentioned by several, I point out again that no one to my

knowledge was ever made uncomfortable by the former inclusion of fumigatus

in Veniliornis and its subsequent deportation to Picoides (SACC

proposal 263). I disagree with Nacho that expanded Dryobates

doesn’t share common themes – see my first paragraph. At the anecdotal level, I remembering

thinking during my first experiences with Veniliornis that they were

remarkably similar to North American Downy, Ladder-backed, and Nuttall’s

woodpeckers in call note, long call, size, foraging behavior, and plumage

pattern, and wondering aloud why they were placed in a separate genus. The most

colorful species are strictly at tropical latitudes, a widespread pattern in

birds. The comparison to an expanded Hydropsalis

actually illustrates my point, namely the latter would have been unacceptably

heterogeneous in every way. The

hyperbole of portraying this merger as some sort of “retro” move overlooks the

fact that the number of species in a genus is not predetermined, that expanded Dryobates

has roughly the same number of species as Picumnus, that within-genus

heterogeneity is expected even within genera with fewer species, and that newly

circumscribed Dryobates is similar in age to other woodpecker groups

recognized as congeners, which in turn facilitates, rather than hinders,

comparative analyses. Within many or

most woodpecker genera, different clades show different biogeographic patterns

and have different ecologies; that they are not named genera does not prevent

among-group analyses, as demonstrated in numerous published comparative analyses

that name their units ‘Clade 1, Clade 2, Clade 3’ etc, even if no handy

subgeneric names are available (as in broad Dryobates). An expanded Dryobates is less

heterogeneous than is currently broadly defined Melanerpes, even if

outliers such as lewis and candidus were removed.”

Comments

from Stotz:

“NO I have come to prefer the 3 genus

approach. The expanded Dryobates

hides a lot of interesting evolution that would be more apparent with the

recognition of 3 genera. The 3 genera

make sense biogeographically. The cases

of plumage convergence within the complex like villosus and pubescens

get lost in the big genus, the oddity of fumigatus belonging with black

and white species, and black and white mixtus and lignarius

belong with the brown Veniliornis is lost. I just think there is more useful information

with 3 genera.”