Proposal (864) to South American Classification Committee

Elevate Podiceps occipitalis juninensis to species rank

Background. The form of

Silvery Grebe from the Central Andes was originally named as a subspecies, and

indeed bears close resemblance to the nominate race of Patagonia, except when

the latter is in its striking breeding plumage. Lacking a distinct non-breeding

plumage, juninensis is actually more

similar to Junín Grebe Podiceps

taczanowskii in all adult plumages except for its smaller overall size but

relatively longer wings, to the extent that specimens can be difficult to

distinguish even in the hand (Peters and Griswold 1943). Until recently, juninensis has generally been treated as

a subspecies, although Chubb (1919) treated it as Podiceps juninensis,

without further comment but citing Ogilvie-Grant (1898) who, however, had

clearly captioned his account, which followed that of P. occipitalis, “Subsp. a.

Podicepes juninensis”.

New Information. More recently, some authors have suggested that juninensis may be better treated as a full species, and del Hoyo

and Collar (2014) split juninensis on

the grounds of morphology, non-migratory behavior, lack of distinct breeding

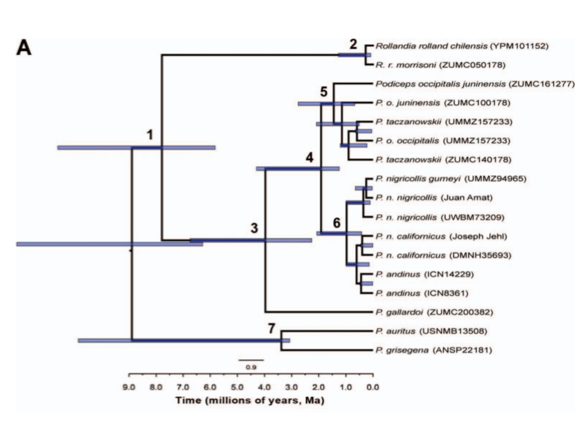

plumage, and higher-pitched voice. In a phylogeny of cytb and COI (see screenshot below), Ogawa et al. (2015) found that juninensis, taczanowskii, and occipitalis

formed a clade, but that the two samples of juninensis

(which were not reciprocally monophyletic) were basal to the clade containing taczanowskii, with the single sample of

nominate occipitalis embedded within taczanowskii. Ogawa et al. (2015)

suggested that the lack of reciprocal monophyly between the two juninensis samples may be due to the

isolated Colombian Andes population possibly being a genetically distinct

undescribed taxon. In any case, according to this phylogeny, juninensis is less closely related to taczanowskii and occipitalis than the latter two are to each other, and the

estimated age of divergence between juninensis

and taczanowskii + occipitalis is a little more than 1.5

myr.

Fig. 2A of Ogawa et al. (2015).

Conclusions. The case of P. occipitalis juninensis seems a

somewhat analogous situation to Andean Teal Anas

andium and Puna Teal Spatula puna,

which are now considered full species by SACC (Remsen et al. 2020), and a

stronger case for species status than the Colombian Grebe P. andinus, which is embedded within Eared Grebe P. nigricollis as currently recognized.

Proposed Changes. A YES vote for Part A of this proposal (strongly recommended) would be

for the treatment of juninensis as a

full species, Podiceps juninensis.

As for English names (if A passes), ‘Northern

Silvery Grebe’ was used for P. juninensis

and ‘Southern Silvery Grebe’ for P.

occipitalis by del Hoyo and Collar (2014); they are apt and have gained

currently through HBW/BLI and e.g. Guevara et al. (2016), but they are a bit

long and bland. The group names used by Clements et al. (2019) are ‘Andean’ and

‘Patagonian’, respectively; if used in combination with ‘Silvery’, ‘Patagonian

Silvery Grebe’ is overlong with 9 syllables. Only two grebes are widespread in

the Andes, and only one is widespread yet a breeding near-endemic to Patagonia

(though Great Grebe Podiceps major comes

close). A hybrid option would be ‘Andean Grebe’ and ‘Silvery Grebe’, which has

the advantage of retaining the name of the most widespread form.

Thus, if voting yes for A please vote on Part

B for either ‘Northern Silvery Grebe’ and ‘Southern Silvery Grebe’; ‘Andean

Grebe’ and ‘Patagonian Grebe’, ‘Andean Grebe’ and ‘Silvery Grebe’, or a

suggested permutation of these.

References.

Chubb, C. (1919). Notes on collections of

birds in the British Museum, from Ecuador, Peru, Bolivia, and Argentina. Part

II. Podicipediformes―Accipitriformes. Ibis 1919: 256–290.

Clements, J. F., T. S. Schulenberg, M. J.

Iliff, S. M. Billerman, T. A. Fredericks, B. L. Sullivan, and C. L. Wood

(2019). The eBird/Clements Checklist of Birds of the World: v2019. Downloaded

from https://www.birds.cornell.edu/clementschecklist/download

del Hoyo., J., and N. J. Collar (2016). HBW

and BirdLife International Illustrated Checklist of the Birds of the World.

Volume 2: Passerines. Lynx Edicions, Barcelona.

Guevara, E. A., T. Santander G., A. Soria, and

P.-Y. Henry (2016). Status of the Northern Silvery Grebe Podiceps juninensis in the northern Andes: recent changes in

distribution, population trends and conservation needs. Bird Conservation

International 26: 466–475.

Ogawa, L. M., P. C. Pulgarin, D. A. Vance, J.

Fjeldså, and M. van Tuinen (2015). Opposing demographic histories reveal rapid

evolution in grebes (Aves: Podicipedidae). The Auk: Ornithological Advances

132: 771–786.

Ogilvie-Grant, W. R. (1898). Catalogue of the

Birds in the British Museum. Vol. 26.

Steganopodes (Cormorants, Gannets, Frigate-Birds, Tropic-Birds, and

Pelicans), Pygopodes (Divers and Grebes), Alcae (Auks), and Impennes

(Penguins). Trustees, London.

Peters, J. L., and J. A. Griswold, Jr. 1943.

Birds of the Harvard Peruvian Expedition. Bulletin of the Museum of Comparative

Zoology 92: 280–327.

Remsen, J. V., Jr., J. I. Areta, C. D. Cadena,

S. Claramunt, A. Jaramillo, J. F. Pacheco, J. Perez Emán, M. B. Robbins, F. G.

Stiles, D. F. Stotz, and K. J. Zimmer (Version 11 February 2020). A

Classification of the Bird Species of South America. American Ornithological

Society. http://www.museum.lsu.edu/~Remsen/SACCBaseline.htm

Pamela C. Rasmussen,

July 2020

Note on

Remsen for voting: Unless one of the proposed English names gets a 2/3 majority

from English name subcommittee, I’ll convert the results into a separate

proposal that uses the winner of this vote as the starting point.

Comments

from Robbins: “YES. To help evaluate differences in breeding plumage that Pam

mentions, I'm pasting in a few eBird checklists that have unequivocal birds in

breeding plumage of each occipitalis taxon:

https://nam04.safelinks.protection.outlook.com/?url=https%3A%2F%2Febird.org%2Fchecklist%2FS53665186&data=02%7C01%7Cnajames%40lsu.edu%7C0be9fe96f39849361d5808d82cb33ded%7C2d4dad3f50ae47d983a09ae2b1f466f8%7C0%7C0%7C637308495634499516&sdata=6R4NxdoQRxrfS7%2BrYz2jJc2kiSOU2E6SAeOGySkqpxM%3D&reserved=0

https://nam04.safelinks.protection.outlook.com/?url=https%3A%2F%2Febird.org%2Fchecklist%2FS21087057&data=02%7C01%7Cnajames%40lsu.edu%7C0be9fe96f39849361d5808d82cb33ded%7C2d4dad3f50ae47d983a09ae2b1f466f8%7C0%7C0%7C637308495634499516&sdata=wQPsnycmZqoHkAg6HxWoeKEHgSONWV2rX2G4KhRkD7Y%3D&reserved=0

https://nam04.safelinks.protection.outlook.com/?url=https%3A%2F%2Febird.org%2Fchecklist%2FS27026845&data=02%7C01%7Cnajames%40lsu.edu%7C0be9fe96f39849361d5808d82cb33ded%7C2d4dad3f50ae47d983a09ae2b1f466f8%7C0%7C0%7C637308495634499516&sdata=WqHSsDBIw8M5ekx0vkRj6EjesMSRrHCv400LXYNqNfo%3D&reserved=0

https://nam04.safelinks.protection.outlook.com/?url=https%3A%2F%2Febird.org%2Fchecklist%2FS65088774&data=02%7C01%7Cnajames%40lsu.edu%7C0be9fe96f39849361d5808d82cb33ded%7C2d4dad3f50ae47d983a09ae2b1f466f8%7C0%7C0%7C637308495634499516&sdata=XQB8bob9XAr662Hr7y%2FQOelM2OfoMIU6njscz6cZ0M4%3D&reserved=0

Comments from Areta: “NO. The issue with these grebes is not

so easy from my perspective, and while there are extremes of (mostly)

geographically structured morphological variation that have been usually

recognized as juninensis, taczanowskii, and occipitalis, I

feel that more information is needed to recognize juninensis as a full species. The situation might be more fluid

than what current studies show, and we may be jumping the gun by simplifying

the case.

“It is worth noting

that in several paragraphs Ogawa et al. 2015 refer to "incipient

species" and not to "full species" when mentioning taczanowskii and andinus. The first two paragraphs of the discussion show the

careful approach of the authors when dealing with taxonomic treatment of these

forms. And the last paragraph of Ogawa et al. 2015 (p.781) indicates that

"we conclude that the now extinct P. andinus represented a newly

established lineage and incipient species among Podicipedidae. Furthermore, and

consistent with a tendency for rapid speciation in grebes, P. andinus may represent one of several incipient species, as is

indicated by DNA barcode data on P.

taczanowskii (Junin Grebe; this study) and the Aechmophorus occidentalis–A.

clarkii (Western Grebe– Clark’s Grebe) complex"

“First of all, Thomas

Valqui first and myself later found many individuals at Lake Junin (where taczanowskii and juninensis coexist) that were difficult to identify to species.

This may suggest that there is ongoing hybridization between them (perhaps

triggered by the recent population declines in taczanowskii? for which see Valqui 1994. Or perhaps this was always

the case?). I am unaware of published information in this regard.

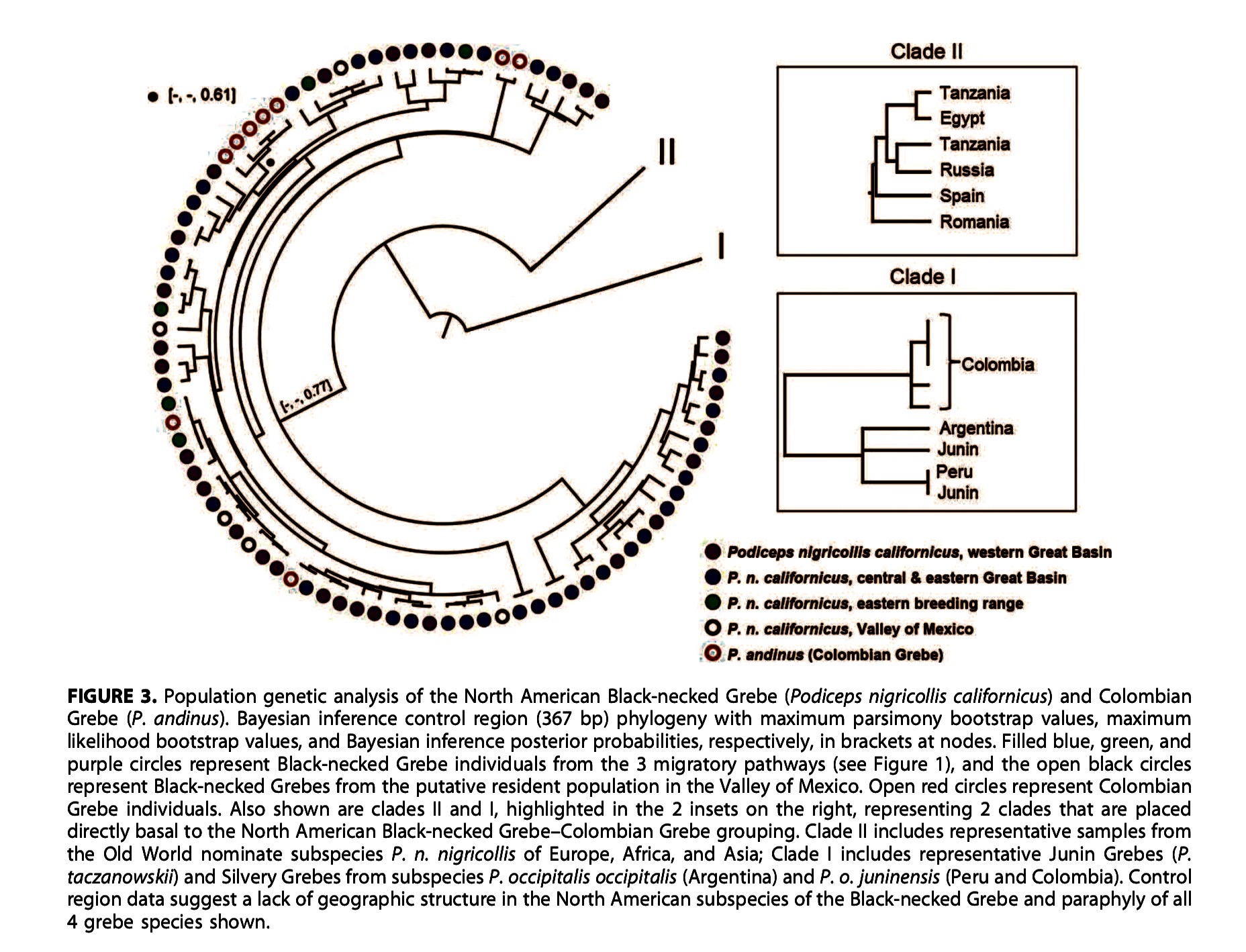

“Second, the

phylogenetic relationships shown in the Cyt-b+COI tree differ from the control

region (Figure 3 in Ogawa et al. 2015). If we focus on the Cyt-b+COI tree, then

both taczanowskii and juninensis would be non-monophyletic:

with one juninensis (from Lake Junin) being more closely related

to occipitalis+taczanowskii than to the other juninensis

(from Lagunillas); similarly, the clade of occipitalis+taczanwoskii shows that the single

sample of occipitalis is more closely

related to a taczanowskii than to the

other sample of taczanowskii. In

looking at the control region inset (Clade I), the Colombian birds seem more

distinct than juninensis, occipitalis and taczanowskii from Peru and Argentina, while the relationships among

the latter three differ from those in the Cyt-b+COI tree: there is a polytomy

involving occipitalis (Argentina), taczanowskii (Junin) and a clade

including one taczanowskii (Junin)

and one juninensis (Peru). Thus, for

different reasons, taczanowskii and juninensis are not monophyletic in both

datasets. The only solid conclusion that I can draw from Ogawa et al. (2015) is

that genetic differentiation between juninensis,

taczanowskii and occipitalis is reduced, and that more samples and further genetic

analyses are needed to understand how genetic variation parses out among. I do

not think that paper provides compelling evidence for a split (and the paper

itself does not claim this).

“To conclude, I find

the genetic data presented in Ogawa et al. (2015) as insufficient evidence to

elevate juninensis to species. A

stronger case for the split could possibly be made by integrating vocalizations

(there are no published analyses, not even spectrograms), differences in

plumage patterns (indeed, taczanowskii

is more similar to juninensis than to

occipitalis) and geographic

distributions while assessing for the existence of intermediates in a

comparative phylogenetic framework (this is missing, as no one has really

looked into this). The plumage differences between juninensis/taczanowskii

and occipitalis seem clear, but are

not as marked as those between undisputed species. As Alvaro mentioned for

Chile, occipitalis and juninensis also overlap to some extent

in the Puna of NW Argentina, but no one (to my knowledge) has studied the

situation in detail. Until solid genetic and natural history data is properly

analyzed, I prefer to err on the side of caution by leaving juninensis as an arguably quite

diagnostic subspecies of occipitalis.

In the long run, the evidence may show that occipitalis

and juninensis are different species,

but this evidence should be gathered systematically, carefully analyzed and

published. At present, I see many gaps, conflicting data and key unanswered

questions to make this decision.

“See: Valqui,

T. (1994) The extinction of the Junin Flightless Grebe? Cotinga 1:

42–44.”

Comments

from Jaramillo:

“YES. Additional

information on these from Chile: On several occasions we have seen occipitalis

in flocks of juninensis in Lake Chungara up by the Peru/Bolivian

borders. Steve Howell has also found them up there in flocks of juninensis.

This is in the October-November time frame, so breeding season. Note that there

is a well-documented record of occipitalis in southern Peru. Apart from

the golden plumes, look at the dark throat and chin which juninensis

will not show. This is a September record, so pre-breeding season for occipitalis. https://nam04.safelinks.protection.outlook.com/?url=https%3A%2F%2Febird.org%2Fchecklist%2FS48454501&data=02%7C01%7Cnajames%40lsu.edu%7C47c87a67084743b1da2008d82cdfaea8%7C2d4dad3f50ae47d983a09ae2b1f466f8%7C0%7C1%7C637308686527250172&sdata=MV6m%2FzrQxA50OX1ezO6LZWWnfRMMxopJ2yCC4fzyxVI%3D&reserved=0

“There is no way to assess what is going on, other that there is

sometimes sympatry during the early part of the breeding season (on Chungara we

see nests of juninensis in Oct-Nov). The occipitalis may be

migrants that will leave, I don't know? I assume that is the case. There is no

evidence of hybridization that we know of. But do keep in mind that occipitalis,

unlike juninensis, is highly migratory. Migration and distinct change

from a breeding to a non-breeding plumage is of interest, versus juninensis

that looks about the same year round and is resident.”

Comments from Claramunt: “NO. Differences in facial

patterns are very suggestive, I admit I was tempted to vote YES, but we need

some minimal analysis of the geographic distribution of the character to

evaluate the potential existence of intermediate populations. And then, the Ogawa

et al. paper shows a very complicated picture of mitochondrial relationships

with no clear genetic clades coinciding with taxonomy nor with phenotypic

similarity, suggesting no clear separation of species-level lineages, including

taczanowskii. I could not find the DNA sequences in GenBank, so no

chance of doing some further analyses (strange, I think The Auk requires

publication of sequences). Rather than splitting juninensis, these

results rise the question of whether taczanowskii should be considered a

separate species (cf. also Nacho’s comment).”

Additional comments from Jaramillo: “I was

looking through where the closest points of contact may be between these two

forms, and seeing if I could come up with some imagery. An interesting record I found is this one from

Jujuy in January with both forms together. Apart from the throat coloration differences,

and the golden plumes versus silvery the crown/nape contrast is another

difference. The form juninensis

has a darker crown, not as contrasting as on occipitalis. They also look

different from behind. In any case, I thought this record of sympatry would be

interesting:

Additional comments from Claramunt: “Alvaro,

I hear you. Phenotypically, they seem

two different species, in my mind. But the genetic data suggest a different

scenario. The facial pattern may be the

result of a single (or just minimal) genetic difference in a background of

genomic uniformity (or at least not diverging).

The genetic basis of the trait may not

allow for intermediate forms and interbreeding may be invisible. Then the presence of both phenotypes

in a single population can be interpreted as a local polymorphism and a

confirmation that the two phenotypes behave, socially, as a single species. The point is that, without additional data, we

cannot interpret co-occurrence as evidence of reproductive isolation.

“If they are breeding sympatrically, observing whether pairs sort

out by phenotype or whether there are phenotypic intermediates would be very

informative.”

Comments

solicited from Jon Fjeldså: “I am glad to see that you take up the ranking of these

grebes, as I was quite irritated to see P. occipitalis and juninensis

being split in The HBW/BirdLife illustrated checklist. However, I can probably blame myself, since

nearly 40 years ago I myself published some evidence for splitting them (see

Fjeldså J 1982. Some behaviour patterns of four closely related grebes, Podiceps

nigricollis, P. gallardoi, P. occipitalis

and P. taczanowskii, with reflections on phylogeny and adaptive

aspects of the evolution of displays. Dansk Orn. Foren. Tidsskr. 76: 37-68. Here, I described some differences in displays

and calls between silvery grebes in Peru and southern Patagonia. However, these populations are far apart, and

I really don't know how much variation there could be in behavior within the

large intervening area. In fact, there seems to be a good deal of flexibility

in grebe behavior, in whether they use face-to-face dancing or parallel rushes

or 'barging'.

“Since

then, I discovered perfectly intermediate specimens (between occipitalis

and juninensis) in museum material from around Coquimbo in Chile. This

suggested a rather narrow zone of genetic mixing in the zone of contact between

southern and northern morphotypes, but in fact there are also indications of

geneflow over deeper time since juninensis birds from northern Chile,

Bolivia and southern Peru (Puno, Arequipa) generally have somewhat

golden/brass-like luster to the ear plumes (but white throats), in contrast to

dull greyish-brown ear-plumes in all populations from Junín and Ancash through

Ecuador and Colombia. So clearly there is a rather gradual transition in

morphology between occipitalis and juninensis (but no detectable

difference between Junín-Ancash and the northern Andes).

“The

result by Ogawa et al. was surprising (note that I was co-author here), because

of the genetic break between specimens from the south+Junín+Ancash and the

northern Andes. So there is a discordance between morphological and molecular

signals here. I think many more genetic samples are needed (with multiple

markers for telling apart effects of gene flow and ancestral polymorphism)

before we can tell whether there is a basis for splitting up the Silvery Grebe.

With present techniques, it should be quite straight-forward to obtain adequate

genetic data (broad geographical sampling) from toepads of museum specimens,

with no need for collecting fresh samples.

“P.

taczanowskii is another issue. Although placed next to an occipitalis

sample in the Fig. by Ogawa et al., there is no doubt from my old work in Junín

that this population, which probably originated during a period of glacial

isolation in the Junín Basin, is reproductively isolated from juninensis.

P. juninensis and taczanowskii may sometimes display together,

but using rituals that have nothing to do with pair formation (but rather a

sign of mild/ritualized aggression), and in many contexts, for instance during

foraging, they decidedly avoid one another. They are clearly aware that they are

different. I am rather skeptical about

claims of intergradation by the two species in lake Junín. On the contrary, my morpho-data (in several

publications) indicate divergence (ecological character displacement), but I

have seen one bird that could be an hybrid (but casual hybrids are also known

between occipitalis and gallardoi, and between other well-marked

grebe species). To check if there could have been a recent breakdown in the

genetic integrity of taczanowskii I checked photos available on Google

(assuming that most of these have been uploaded in recent years). One bird

labelled as taczanowskii was a clear occipitalis, 3 were

difficult to identify (because of angle of view, or resolution), but 71 were

clearly taczanowskii. Therefore, I don't see any evidence of

hybridization but rather think that some people have difficulties with

identifying the species. Again: more genetic data are needed. Ogawa et al.

provided some indication that isolated local populations of grebes can rapidly

diverge and evolve their own integrity, although they are nested within

widespread species in phylogenies using few genetic markers.

“There

is no reference to any of my old papers (1980s) on Peruvian grebes in the reference

list to Proposal 864 (reprints of these should be deposited in several American

museums, and at least they are summarized in my 2004 book 'The Grebes' from

Oxford Univ. Press).

“My

conclusion: Keep occipitalis and juninensis as one species and

maintain taczanowskii (as well as andinus, based on the arguments

provided by Ogawa et al.) (a separate question is then whether Podiceps nigricollis

should be split up with separate species in the Nearctic and in the Old World

(and maybe a third species in South Africa).

“I

hope this is useful for your decision.”

Comments

from Bonaccorso:

“NO. The case is complicated in so many dimensions

(plumage, vocalizations, natural history, distributions) and so unclear

regarding phylogenetic evidence (e.g. cytb and COI vs. control region) that I

think that elevating this taxon to species requires a paper on its own. As said

before, a systematic revision of all qualitative and quantitative evidence and,

probably, more genetic information will be needed to make an informed decision.”

Comments from Pacheco: “NO. Further studies may show

that occipitalis and juninensis are different species, but this

evidence still needs to be collected in the key areas and analyzed in an

integrated manner. As highlighted by Nacho, the article by Ogawa et al. does

not provide convincing evidence for a division.”

Comments from Zimmer: “NO. I was on the fence with this one, mainly

due to occipitalis being migratory

and having distinct breeding and non-breeding plumages, in contrast to juninensis. However, after considering comments from

several other committee members, and, in particular, Jon Fjeldså, I am

persuaded that we simply don’t know enough about what is going on to justify

splitting at this time.”

Additional

comments from Jaramillo: “I realize that I am against the tide here, but that is

fine. I think longer term with more data we will sort this one out as two

species. There seem to be some unusual aspects in grebes that I certainly do

not understand. Aechmophorus grebes breed sympatrically, sometimes

hybridize but actually tend to mate assortatively from what I understand. Vocal

differences are there, but minor really, plumage and bill color differences

consistent but minor. Podiceps nigricollis has these relatively large

genetic differences between populations (New World and Old World separated 1

million years ago), yet little morphological, or at least plumage differences.

In the New World we have three examples at least of flightlessness developing,

and for the most part the plumage of these birds has remained (at least 2 of 3)

quite similar if not nearly identical to the flying sister species. In all

cases the sister is sympatric with the flightless population. It is a mystery

to me how this happens, was it sympatric speciation? If so, how come the

plumages are so conserved? Then we have the rather spectacular array of

face/neck ornamentation in this group, and often a molt into a dull

non-breeding plumage. Surely these ornaments are of some use, some purpose and

some use in pair formation.

“In any case, I considered Santiago’s points

and I do not think that this is what is going on. I do not think that this is a

morph, or at least a situation where hybrids may go undetected due to a genetic

situation where intermediates would not be expressed. As I looked at more

photos, there does seem to be a zone where you can find intermediates, and

Fjeldså noted this as well. I am not sure about his interpretation of a wide

zone of gene flow. But there is a contact zone, and certainly some hybridization.

As such perhaps some would suggest that this be studied in more context, and

that is reasonable. But at this point the differences in ecology, display

features (breeding plumes), resident vs migrant situation, and seemingly little

or a narrow zone of interbreeding. I am sticking with my YES vote to split

these two.”

Comments from Remsen: “NO. Alvaro may be correct, but this is a

complicated case that needs more research before we make a change, as noted by

several comments above, including Jon’s, whose input is much appreciated.”