Proposal (865) to South American Classification Committee

Elevate Catharus

dryas maculatus to species rank

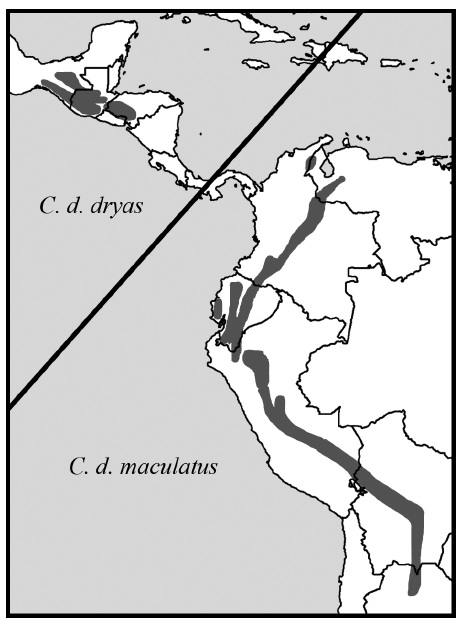

Background: This proposal is

based on the SACC footnote for the species currently listed as Catharus

dryas (Turdidae):

5cc. Halley

et al. (2017) provided evidence that the South American maculatus subspecies

group should be treated as a separate species from (extralimital) nominate

subspecies group from Middle America. SACC proposal

badly needed.

During

the 1850s, two species were recognized by Gould (1855) and Sclater (1858),

diagnosed by their coloration within the genus Catharus (= Malacocichla):

C. dryas in Central America and C. maculatus in South America,

respectively. However, Salvin and Godman (1879) proposed that C. maculatus

should be treated a subspecies of C. dryas, because variation they

proposed that variation in coloration between the two could be due to

post-mortem fading. This suggestion was adopted in all subsequent

classifications, from Hellmayr (1934) through Dickinson & Christidis

(2014). i.e. a single species with two disjunct subspecies. Below is

distribution of the species with the two disjunct subspecies separated by the

dark line (taken from Halley et al. 2017, which is based on NatureServe

InfoNatura)

New

Information:

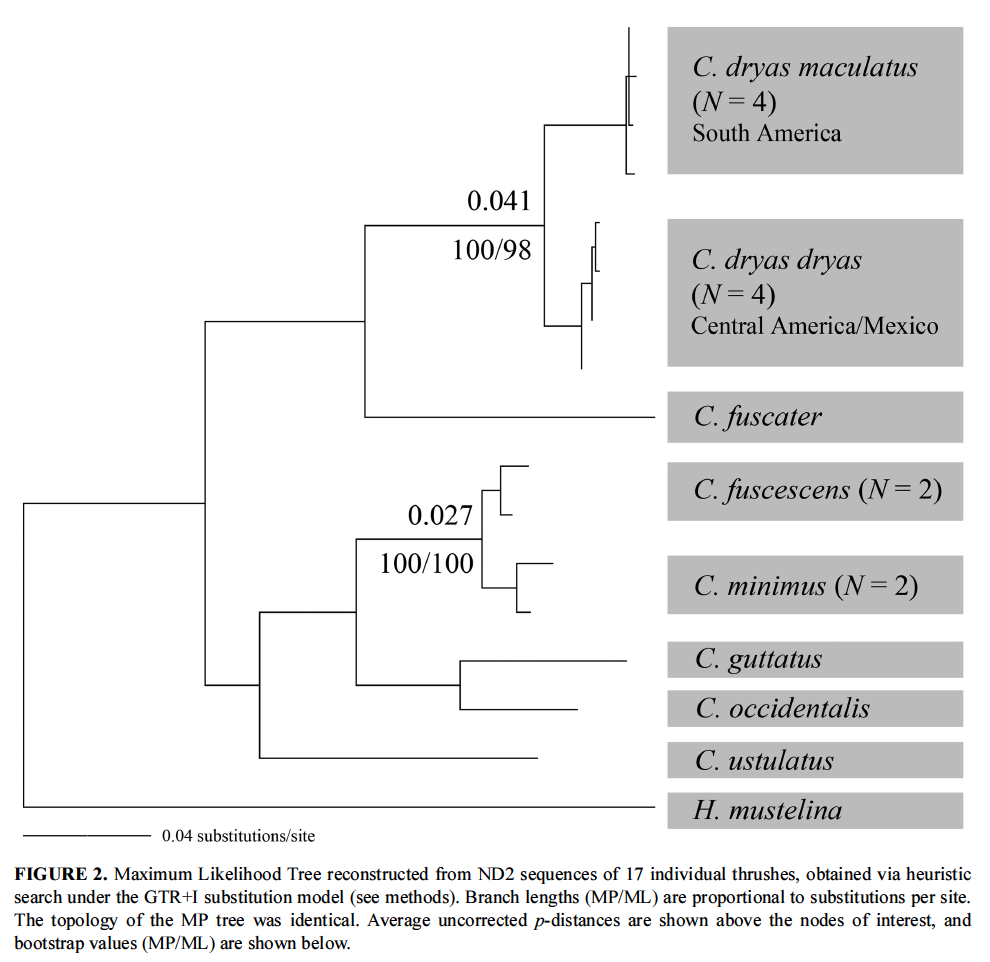

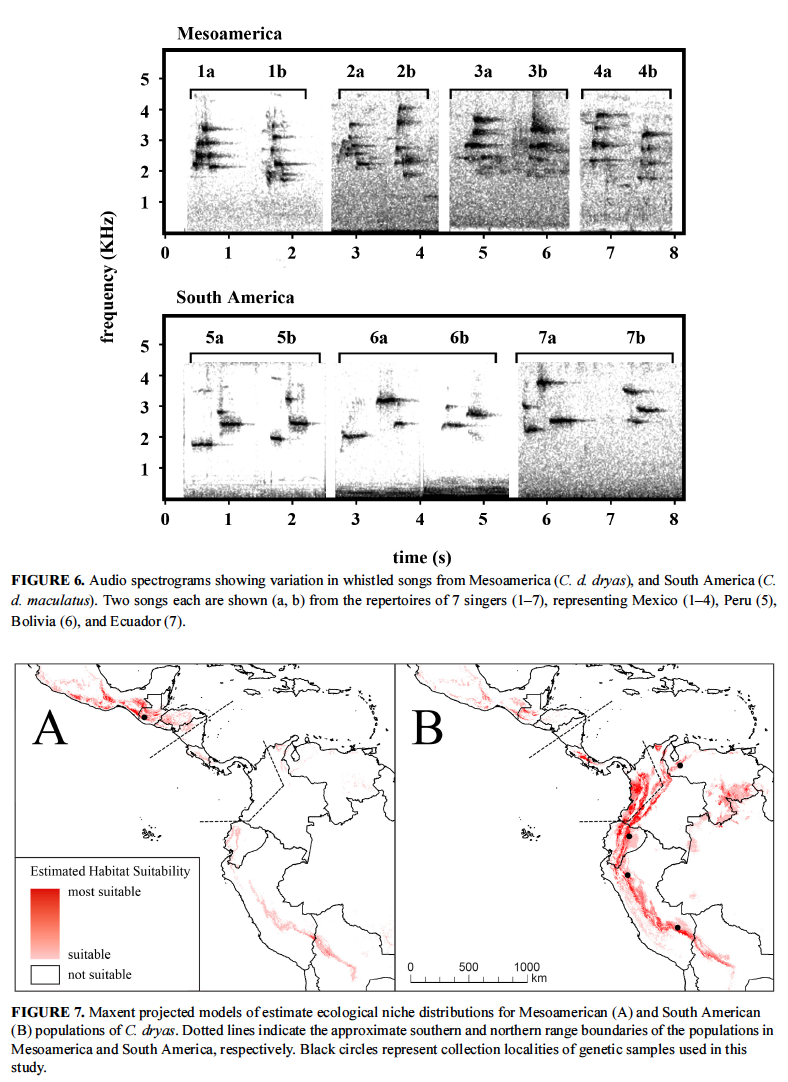

Recent research by Halley et al. (2017) provided multiple lines of evidence

to support the treatment of the two populations as separate species. The two species were 100% diagnosable by

genetic, vocal, morphometric, and plumage characters. Furthermore, Ecological

Niche Modeling indicates divergent ecological niches (see below figures from

Halley et al. 2017 of the genetic, whistled song and ENM evidence). Halley et al. (2017) found that the two

groups were reciprocally monophyletic (although N=8 individuals sampled) sister

species, with independent and divergent evolutionary lineages including

different ecologies.

Recommendation: Based on the recent

data provided by Halley et al. (2017), we divide this proposal into two

parts, for each of which we recommend a YES:

A. Treat the South

American population of the current Catharus dryas (in SACC) as a

separate species, Catharus maculatus.

B. Change the English

name of the South American species to Sclater’s Nightingale-Thrush, as in

Hellmayr (1934), as pointed out by Halley et al. (2017). Although the Middle

America species is not in the scope of SACC, a change must be also considered

by NACC for Catharus dryas (sensu stricto), possibly with the

English name Gould's Nightingale-Thrush (Gould 1855) as in Hellmayr (1934). The

rationale to discontinue use of “Spotted” name is well-justified by Halley et

al. (2017), because at least five other species in the genus are spotted in

adult plumage (and all juveniles indeed are spotted).

Pertinent

literature:

Gould, J. 1855.

Description of a new bird from Guatemala, forming the type of a new genus.

Proceedings of the Zoological Society, 22, 285.

Halley, M. R., J. C.

Klicka, P. R. S. Clee, And J. D. Weckstein.

2017. Restoring the species

status of Catharus maculatus (Aves: Turdidae), a secretive Andean

thrush, with a critique of the yardstick approach to species delimitation. Zootaxa 4276: 387–404.

Hellmayr, C.E. 1934.

Catalogue of birds of the Americas and the adjacent islands in Field Museum of

Natural History, including all species and subspecies known to occur in North

America, Mexico, Central America, the West Indies, and islands of the Caribbean

Sea, the Galapagos Archipelago and other islands which may be included on

account of their faunal affinities. Field Museum of Natural History, Zoological

Series, 13 (7), 1–531.

Salvin, O. and F. D.

Godman. 1879. Biologia Centrali-Americana. Vol. 1. Aves. R.H. Porter, London,

512 pp

Sclater, P.L. 1858.

Notes on a collection of birds received by M. Verreaux of Paris from the Rio

Napo in the Republic of Ecuador. Proceedings of the Zoological Society of

London, 26, 59–78.

Natalia J. Pérez-Amaya

and Orlando Acevedo-Charry, July 2020

Comments

from Robbins: “YES. The Halley et al. (2014) paper clearly demonstrates that

Mexican and Central American birds are distinct in multiple parameters from

South American birds. Thus, I vote to

recognize nominate and maculatus as species.”

Comments from Areta: “YES. A comprehensive data set

that provides compelling evidence of two species. The reciprocal monophyly and

the differences in vocalizations are to me the two most important lines of

evidence of the many provided by Halley et al. (2017).”

Comments from Claramunt: “YES. Subtle but diagnostic plumage and song differences plus some

morphometric differentiation and reciprocal mitochondrial-lineage monophyly

provide good evidence for species status.

Comments from Stiles: “YES -- maculatus

clearly deserves species status, and Sclater's N-thrush seems OK as an E-name.”

Comments

from Bonaccorso:

“YES. The phylogenetic evidence separates both taxa

with good support, and the genetic divergence between them is much higher than

that between C. fuscescens and C. minimus. Also, there is a

substantial geographic gap between both, which suggests that gene flow is

absent. Together with differences in plumage, voice, morphology, and ecological

niche, I think that species status is clear-cut.”

Comments from Pacheco: “YES. Multiple evidence converges

on the treatment of these two taxa as separate species.”

Comments from Zimmer: “A) YES.

Halley et al. (2014), using multiple data sets, demonstrates

conclusively that South American maculatus

should be considered a species distinct from Mexican/Central American dryas.

(B) “YES” to using “Sclater’s Nightingale-Thrush” as the English name

for maculatus. This would represent not only the

resurrection of a name used by Hellmayr, but it would also be nicely

symmetrical should NACC revert to “Gould’s Nightingale-Thrush for dryas, as has been suggested.”

Comments

from David Donsker: “If we’re going to try to avoid

the obvious eponyms, Gould’s and Sclater’s Nightingale-Thrush, for the two

species it’s a bit tricky.

“I see that the SACC wants to avoid “spotted” since that’s

used for the parent species and since that feature doesn’t help distinguish

either of the two daughters much from virtually all of the other Catharus

thrushes.

“But adopting the adjective “maculated,” for the South

American species, a direct borrowing from the Latin epithet maculatus, might

be helpful. That adjective, which essentially means the same as “spotted”, but

at least to me has a shade of meaning that suggests more obvious, heavier, or

larger spots, might be acceptable. So, perhaps Maculated Nightingale-Thrush for

C. maculatus would do.

“The Middle American species is trickier, for sure.

Translations of none of the species or subspecies Latin epithets is

particularly helpful. One is an eponym, another a localized toponym and the

species epithet, dryas, which I assume refers to “oak” in this case, doesn’t

really describe its favored habitat, I believe.

“When stumped, I like to see what these

species are called in the languages other than English that may apply.

According to Howell & Web, the Spanish name for C. dryas is Zorzalito Pechiamarillo,

“Yellow-chested Thrush".

Using that name as a model, Yellow-throated Nightingale-Thrush wouldn’t be bad.

No other Catharus has a clear

yellow throat, and the clear yellow throat distinguishes it from C.

maculatus which has a dark or heavily-spotted throat.

“That would open the door for another choice for C. maculatus:

Spot-throated Nightingale-Thrush. This name might be a more preferable choice

than “Maculated Nightingale-Thrush”, which invokes the unfamiliar and

uncommonly used adjective ‘maculated’.

“So, these are my

best shots:

C. dryas Yellow-throated Nightingale-Thrush

C. maculatus Spot-throated Nightingale-Thrush or Maculated Nightingale-Thrush”

“I'd like

to clarify why I've recommended ‘Yellow-throated’ rather than ‘Yellow-chested/breasted’

for C. dryas because it does affect the rationale for the English name

suggestion ‘Spot-throated Thrush’ which was an alternative choice submitted for

C. maculatus. It's not to

rigorously describe the extent of yellow on the underparts of C. dryas,

but rather to focus on a plumage characteristic that distinguishes C. dryas

from the very similar C. maculatus. Both have yellowish breasts,

but it's the clear yellow throat of the former as opposed to the spotted throat of the latter that is a

feature which sets them apart in this regard.

“Similarly

the name ‘Spot-throated’ Thrush for C. maculatus is not to

suggest that the spots are only limited to the throat, only to contrast their

distribution in that species to the clear yellow throat of C. dryas.”

Comments

from Lane:

“A) Yes. The vocal differences between this group and

the dryas group are notable, and given the geographic distance between

them, it seems like the isolation of the two must have been long. B) NO. I am

heartbroken to consider using Eponyms for these two stunning thrushes, arguably

the most attractive in the Americas! Their startlingly peach-colored breasts--a

color that fades quickly after death, and so not appreciated by most

museum-based ornithologists until the latter part of the 20th century!--would

seem a character worthy of use in a name for one. Alternatively, "maculatus"

can translate to "speckled" which still aptly describes the

unique plumage (within the tropical Catharus, anyway). I can understand

David Donsker's interest in focusing on the throats

of the two sister species, but similarly to calling Pheucticus chrysogaster

"Golden-bellied Grosbeak," this seems to me a bit too myopic when the

average observer is taking in these two glorious birds. I would probably prefer

"Speckled Nightingale-Thrush" for C. maculatus, and

float some more glitzy name such as "Glowing Nightingale-Thrush" or

"Sunset Nightingale-Thrush" some such to NACC for C. dryas.

Just my two cents.”

Comments from Schulenberg: “B. YES. I have a vote, via SACC,

on the English name for Catharus maculatus. I don't have a vote on the

English name for Catharus dryas, which is a question for NACC;

but I hope that some of the discussions on this page filter up to NACC when

this comes before them. So, with regard to what I guess is SACC Proposal 865B

(English name for Catharus maculatus), I am fully on board with David's

suggestion of Spot-throated Nightingale-Thrush: put me down for a big YES.

“As far as Catharus dryas is concerned, I'm also happy with

the direction that David pointed us in by focusing on the base color of the

underparts of Catharus dryas. I'm also glad that David steered clear of

'Yellow-chested'. Whatever the merits of this formulation in terms of the

fidelity of the translation. '[color]-chested' in English bird names usually

refers to a discrete and high contrast patch of color on the upper breast:

think of Black-chested Tyrant, Black-chested Buzzard-Eagle, White-chested

Swift, Blue-chested Hummingbird, and so on. This clearly is not appropriate for

the nightingale-thrush.

“The next best options that I can think of then

are 'Yellow-throated' or 'Yellow-breasted'. '[Color]-throated' can refer either

to a patch of color limited to or closely centered on the throat, as in

Blue-throated Macaw or Chestnut-throated Seedeater; or, less commonly, it is

used for color patterns that include not only the throat but also the upper

breast (Yellow-throated Toucan) or even most of the underparts (Yellow-throated

Antwren). '[Color]-breasted' usually refers to a pattern where the throat and

breast are the same color (many examples, e.g. Ash-breasted Tit-Tyrant),

although much less commonly it refers to a color that is different from that of

the throat (such as Orange-breasted Bunting). David went with 'Yellow-throated'

at least in part to contrast this to 'Spot-throated' for maculatus. My

guess is that this point may be too subtle in light of the broader picture of

how -throated vs – breasted are used. That said, I could live with either

formulation, but my preference would be 'Yellow-breasted' , as I see this as

more consistent with how the color pattern of the underparts of Catharus

dryas typically is described in bird names".

Comments from Remsen: “A. YES, based on the vocal

differences. The rest of the information

used to support species rank by Halley et al. is insufficient without the vocal

data. Morphological diagnosability

serves only to show that they are valid taxa, species or subspecies. To use “reciprocal monophyly” as a criterion

when there is a grand total of 4 individuals from each population is nearly

ludicrous. The awesome-sounding

criterion “reciprocal monophyly” is greatly over-rated in my opinion. This criterion is always one additional

sample away from being reversed, and given the presence of rare alleles, small

samples are simply insufficient to assess reciprocal monophyly. Additionally, unless those samples come from

the populations closest to each other, the interpretation must be cautious –

those samples are the ones most likely to reflect shared alleles due to past

gene flow. As for niche modelling data

…. numerous taxa treated as species have populations that occupy radically

different niches. Differences in habitat

preferences etc. among populations within taxa that are universally treated as

species, often without any subspecies designation, are rampant -- -this is just

a widespread feature of many bird populations and has no taxonomic value. Biologically interesting, of course, but

taxonomically irrelevant in my opinion.”

“B. NO. I like Donsker’s names better, and I think we need a separate

proposal on English names, submitted simultaneously to SACC and NACC. Further, I might be in favor of an eponym for

someone not yet honored or intimately tied to the species beyond a

description. But Sclater already has two

eponymous English names (Sclater’s Antwren, Sclater’s Tyrannulet) as well as 11

species epithets in scientific names (sclateri) on the SACC list. He was an important contributor to the

taxonomy of birds but has already been profusely honored. Finally, if there were not distinctive

phenotypic characters from which to derive a name, that would be one thing, but

this distinctive species is loaded with color and pattern.”