Proposal (868) to South American Classification Committee

Treat

Lepidocolaptes layardi as a subspecies of L. fuscicapillus

Effect on South American CL: If adopted, this proposal would lump two taxa of the genus Lepidocolaptes

presently considered species and would thus recognize the polytypic species L.

fuscicapillus (with nominate and layardi subspecies).

Background: Proposal 620 (2013) proposed the elevation to species rank of all taxa included in

the species previously named Lineated Woodcreeper (Lepidocolaptes

albolineatus). This proposal was adopted in 2014 and has subsequently been

taken over in several worldwide taxonomic lists. (For the background until that

date, see the proposal.)

New information:

1. Proposal 620 states in the background info: “taxa fuscicapillus

and layardi being very distinct vocally, hence suggesting that the

polytypic L. albolineatus may include more than a single species

(Marantz et al. 2003).” However, what is described in this reference for fuscicapillus

is in fact the voice of the (then undescribed) fatimalimae. On the

contrary, they describe the voice of madeirae (=present fuscicapillus)

and layardi as being the same.

2. Proposal 620 states in the new information: “Vocally, these five

molecular clades/taxa have also proved to be very distinct, further supporting

their treatment as independent species (Rodrigues et al. 2013).” However, the

‘proof’ given in Rodrigues et al. (2013) for vocal difference between fuscicapillus

and layardi is nowhere to be found in the text (this publication is in

fact about the description of the new taxon fatimalimae, and only the

vocal difference of this taxon vs. all others is detailed. There is, however, a

single picture of ‘representative sonograms’ that suggests a difference in

voice between fuscicapillus and layardi (see also further) and a

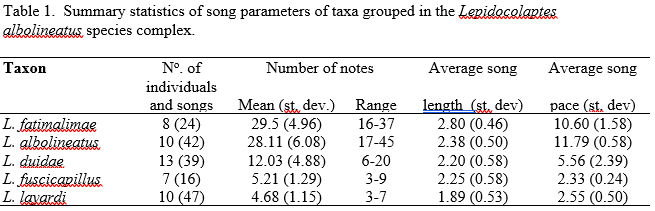

Table 1 in Supplementary Information. I am not sure if this supplementary

information is still available on-line somewhere, for which I copy it here:

From this Table, it is clear that the measured sound

parameters show no significant differences for the taxa fuscicapillus

and layardi (at most a slight difference in song duration with

considerable overlap).

3. Boesman (2016) made a brief analysis of the voice of the Lineated

Woodcreeper complex. As no clear vocal differences could be found between fuscicapillus

and layardi, the specific sonogram depicted in Rodrigues et al. (2013)

was traced back to the original recording. When depicting with appropriate

amplitude levels, the note shape appeared to be quite different and more in

line with other sonograms of both fuscicapillus and layardi (with

note shapes slightly dependent on excitement level of the bird).

4. Independently, Minns (2016) also catalogued all existing xeno-canto

recordings. He states: “The song of layardi is similar to that of its

neighbour fuscicapillus and I was not able to readily distinguish

between them.”

From the above, I believe there is at present no

indication at all that voice of fuscicapillus and layardi shows

anything more than some minor differences.

Rodrigues et al. (2013) also supplied genetic

information (albeit, similar to the vocal information, also in a very condensed

way without providing much detail). From the figure 1 it appears that fuscicapillus

and layardi are the two (sister) taxa which have the smallest genetic

divergence.

Analysis and Recommendation: We have thus here two taxa which at most show some minor morphological

and vocal differences, and which have a considerable mtDNA divergence, which,

however, is the smallest compared to other members of the complex (the latter

additionally DO show significant vocal differences among them as confirmed in

Boesman (2016) and Minns (2016) !).

From the comments of the SACC members on proposal 620,

I deduce that the vocal difference was the main argument to split Lepidocolaptes

albolineatus into four species. With the new information presented here,

this vocal difference is no longer present for the taxa fuscicapillus

and layardi.

Whether the genetic divergence in itself is sufficient

argument to maintain both taxa as full species obviously depends on which

criteria are used. Accepting BSC species level purely on a moderate mtDNA

divergence for two populations separated by a geographical barrier seems at

least rather adventurous and may open the discussion what to do with many other

similar cases.

It is clear that the Tapajos (and Tele Pires) river is

an important geographical barrier, which has led to isolation and speciation in

quite some cases. This in itself however can’t be an argument. After all, Duida

Woodcreeper L. duidae also occurs on both sides of the Rio Negro, an

equally important geographical barrier while at the other hand, it is only

separated from L. albolineatus by the ‘small’ Rio Branco.

Therefore, I propose to reconsider the decision taken

in 2013, would recommend lumping the two taxa and recognize the polytypic

species L. fuscicapillus (with nominate and layardi subspecies).

As for the English name, del Hoyo and Collar (2016)

lump both taxa as a single species and have given it the name Dusky-capped

Woodcreeper (reflecting its scientific name).

Literature cited

Boesman,

P. (2016). Notes on the vocalizations of Lineated Woodcreeper (Lepidocolaptes

albolineatus). HBW Alive Ornithological Note 84. In: Handbook of the Birds

of the World Alive. Lynx Edicions, Barcelona. https://static.birdsoftheworld.org/on84_lineated_woodcreeper.pdf DOI: 10.2173/bow-on.100084

del

Hoyo, J., Collar, N.J. (2016). HBW and BirdLife

International illustrated checklist of the birds of the world. Volume 2:

Passerines. Lynx Edicions, Barcelona.

Rodrigues,

E. B., Aleixo, A., Whittaker, A., and Naka, L. N. (2013). Molecular systematics and taxonomic revision

of the Lineated Woodcreeper complex (Lepidocolaptes albolineatus:

Dendrocolaptidae), with description of a new species from southwestern

Amazonia. In J. del Hoyo, A. Elliott, J.

Sargatal & D. Christie (Eds.), Handbook of the Birds of the World. Special Volume: New Species and Global Index,

pp.248-252. Lynx Edicions, Barcelona.

Marantz,

C., A. Aleixo, L. R. Bevier and M. A. Patten (2003). Family Dendrocolaptidae

(Woodcreepers). Pp. 358-447 in: del Hoyo, J., A. Elliott, and D. A. Christie

(eds.) (2003). Handbook of the Birds of the World. Volume 8: Broadbills to

Tapaculos. Lynx Edicions, Barcelona.

Minns,

J. (2016) Delineating the Lepidocolaptes albolineatus complex. https://www.xeno-canto.org/article/198

Peter

Boesman, July 2020.

Comments

from Remsen:

“YES (depending on comments by others). The

evidence above convinces me that the evidence for the split was over-stated and

not independently analyzed by us as thoroughly as it should have been. With respect to genetic differences, when

restricted to a few neutral loci from a few individuals within taxa of a

monophyletic group, in my viewpoint they are irrelevant to taxon rank.”

Comments from Whitney: “I appreciate with

this well-explained argument of Peter’s, and certainly concur that layardi

is minimally differentiated (if at all) from fuscicapillus. This case is similar to those of other

"HBW woodcreeper" cases (Campylorhamphus, Dendrocolaptes) in

which sample sizes of data used in diagnostic analyses, phenotypic and genetic,

were inadequate (regardless of the conclusions drawn from them).”

Comments

from Claramunt:

“YES. The previous splitting of this species

was done without critical evidence.”

Comments from Robbins: “YES, given Peter Boesman's assessment.”

Comments from Stiles: “YES. Strong vocal similarity and weak genetic

separation without evidence of reciprocal monophyly combine to make its species

status unsustainable.”

Comments from Areta: “YES. The Lepidocolaptes seem to be quite geographically variable in plumage,

but these differences are not paralleled by differences in vocalizations. This

provides an interesting comparison to the case of Lepidocolaptes squamatus/falcinellus in relation to the level of

isolation and the roles of rivers in promoting/maintaining differentiation.

Comments solicited from Jorge Pérez-Éman:

“This

proposal aims to lump Lepidocolaptes

fuscicapillus and L. layardi into

a single polytypic species (L.

fuscicapillus), partially reverting the decision to split L. albolineatus into five species,

including recently described L.

fatimalimae (Rodrigues et al. (2013), Proposal 620). In this proposal,

Boesman argues that data to consider layardi

different from fuscicapillus is

unavailable, and makes the following points:

“1. Early

statements about the large differences between fuscicapillus and layardi

vocalizations were influenced by the known distribution of both taxa by that

time (Marantz et al. 2003). The currently known distribution for each taxon in

the entire L. albolineatus complex is

now better understood by the work of Rodrigues et al. (2013) and, as pointed

out by Boesman, such differences referred to fatimalimae (and not fuscicapillus)

and layardi.

“2.

Rodrigues et al. (2013) provided a molecular phylogeny and stated that the five

monophyletic lineages obtained from this hypothesis proved to be very distinct

vocally. However, Boesman rightly points out that Rodrigues et al. (2013)

focused only on the differences between fatimalimae

and the other taxa, and no detailed analyses were done on the other four taxa (albolineatus, duidae, fuscicapillus and

layardi). He goes further and

indicates that no clear vocal differences were found between fuscicapillus and layardi, and back this up with some general and qualitative

comparative vocal analyses done within this complex (Boesman 2016, Minns 2016).

“I totally

agree with Boesman in relation to these general comments. Rodrigues et al.

(2013) focused on the description of fatimalimae

and consequently, a proposal to split L.

albolineatus into five taxa was not really well supported by their data and

analyses. I think the authors did a great job to better understand the

diversity and distribution of taxa within this species complex, but I don´t

know if by omission or by constraints provided by HBW publishers, there is not

enough information to evaluate the validity of such split. As early reviewers

of Proposal 620 indicated, I was really frustrated trying to find details

associated to detailed information on skin vouchers, recordings and tissues

used in the study. First, the map included in the article is not clear and

details are impossible to see and, second, I am still looking for the

Supplementary Information (besides the Table S1 provided by Boesman). This

information should be readily available to readers/reviewers and it is

particularly relevant when taxonomic changes are proposed. In particular, I

missed a more complete treatment of the morphological variation (although some

of the Zimmer’s [1934] concerns on morphological variation were partly solved

by description of fatimalimae),

including patterns in contact zones among different taxa. Same goes for vocal

and molecular variation. For example, available information for both

morphological/molecular (Rodrigues et al. 2013) and vocal data (Minns 2016)

suggest sympatry in Bolivia, but hybridization has not yet been assessed. A

more thorough specimen evaluation in this region would have provided with a

stronger support to some of their proposed splits by confirming sympatry

without hybridization. Similarly, what are the patterns on both sides of the

Madeira, Tapajos or Teles Pires rivers? These areas have been known to show

complex patterns of phenotypic/molecular variation in other taxa and clear

definition of species/taxon limits should take this into account.

“Boesman´s

criticism on vocalizations analyses done by Rodrigues et al.(2013) are worth to

expand here. The description of L.

fatimalimae vocalizations and their differences to all other taxa within

the L. albolineatus complex are very

detailed and complete. However, there is no similar analysis done with other

taxa vocalizations and the only results shown are included both in Table S1 and

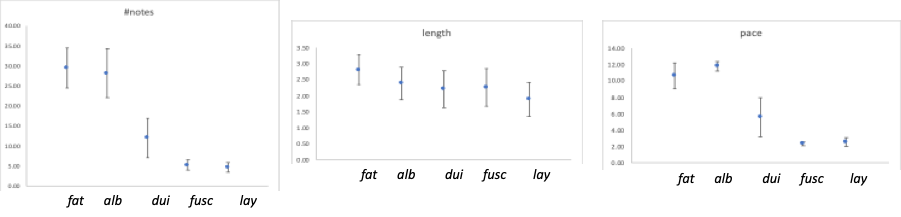

a figure with spectrograms of songs for each taxon. I am providing plots for each

of the vocal characters included in Table S1 to better visualize patterns

(Figure 1).

“Figure 1.

Vocal characters used to compare taxa within the Lepidocolaptes albolineatus species complex (Rodrigues et al.

2013). Number of notes, song length (seconds) and pace (number of notes per

second) data are extracted from Table 1 included in the Supplementary

Information of the HBW Special Volume. Dots represent means and error bars one

standard deviation. Taxa abbreviations: fat

= fatimalimae, alb = albolineatus, dui = duidae, fusc = fuscicapillus, lay = layardi).

“As you can

see, and clearly pointed out by Boesman, these data show no differences between

fatimalimae and albolineatus, or between fuscicapillus

and layardi vocalizations for any of

the three variables. It is also interesting that the first three taxa show a

larger variation in these characters than the last two and, given this

variation, duidae slightly overlaps

with both fuscicapillus and layardi. In fact, songs of these three

taxa were found to be similar by Marantz et al. (2003) describing them as

“slowing, descending series of clear whistles” differing mainly in number of

notes and pace. Moreover, characters such as note shape, frequency, inter-note

intervals and the acceleration/deceleration pattern, useful in the comparisons

with fatimalimae, were not used by

Rodrigues et al. (2013) in these other taxa but certainly should prove useful.

Thus, the authors only “proof” for differences are the “representative”

spectrograms included in their Figure 3. I use quotation marks in

representative because we are just forced to believe or to doubt if those

spectrograms are really typical or not (as no data on variation is included in

the article). In fact, spectrograms provided for fuscicapillus and layardi

are clearly different but, as discussed for Boesman (2016), such differences

depend on how they are presented. As Boesman, I tracked both recordings in

Macauley Library and they clearly are not as different as presented in

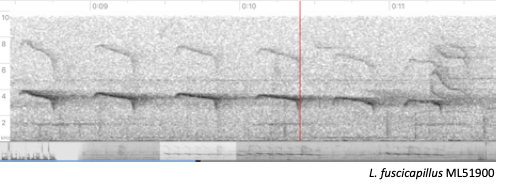

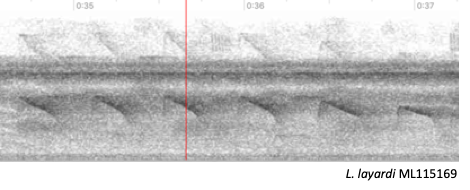

Rodrigues et al. (2013) (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Spectrograms of songs of L. fuscicapillus

(left) and L. layardi (right).

“Song by fuscicapillus shown in Figure 2

(ML51900) is the same depicted in Figure 3 of Rodrigues et al. (2013). It is

not just different but it is also more representative of this taxon songs

(which could be checked reviewing recordings available both in Macaulay Library

and XenoCanto). On the other hand, I am showing a recording of layardi that is not the same as shown in

Rodrigues et al. (2013) as the one shown by the authors is from a bird on

breeding condition (courtship, display or copulation) based on information

provided by the recordist (Curtis Marantz), and such condition might exaggerate

some of the note shapes. When both song spectrograms are visually compared it

is clear they are not as different as portrayed in Rodrigues et al. (2013).

“Consequently,

based on morphological and vocal information, Rodrigues et al. (2013) do not

provide enough information to make any evaluation of the status of the complete

L. albolineatus complex and, more

specifically for this proposal, of the separation of fuscicapillus and layardi.

Boesman (2016) and Minns (2016) qualitative comments are not complete either.

Besides statements/descriptions suggesting that vocalizations of fuscicapillus and layardi are not clearly distinguishable, no formal vocal analysis

was included. Major comparisons are done focusing mostly on albolineatus and fatimalimae, but I am missing an analysis among all taxa, and

quantitative and qualitative comparisons among duidae, fuscicapillus and

layardi are needed. Such comparisons

should have a clear criteria to define what we consider a species under the BSC

used by this committee. Vocalization thresholds are not fixed and could vary

depending on the species groups compared. Additionally, some taxa might not

differ in their loudsongs but their calls might be important to keep

reproductive isolation.

“The last point I would like to

mention refer to the phylogenetic hypothesis and its interpretation. In this

proposal, Boesman states “it appears that fuscicapillus

and layardi are the two (sister)

taxa which have the smallest genetic divergence”. Similarly, Rodrigues

et al. (2013) indicated in their Figure 1 “numbers refer to posterior

probabilities values and genetic distances between sister groups

associated with the labeled nodes”. It is important to understand that the

phylogenetic hypothesis included in Rodrigues et al. (2013) do not show

any sister relationships among fatimalimae,

duidae, fuscicapillus and layardi.

It only shows albolineatus as

potential sister taxon to a unresolved group (polytomy) formed by these four

taxa. Additionally, regardless of the relevance (or lack of) of genetic

divergence for taxonomic decisions, fuscicapillus

and layardi do not show the smallest

genetic divergence, as such divergence is the same among all taxa included in

the polytomy, as clearly indicated in Figure 1 of Rodrigues et al. (2013). The

lack of evidence for sister taxon relationship between fuscicapillus and layardi

is a clear limitation to lump these taxa into a single species. What if fuscicapillus, for example, turned out

to be closer related to duidae? Would

we be asking the same questions?

“As molecular variation within

lineages was not shown by Rodrigues et al. (2013), I downloaded from GenBank

all sequences used in this study plus the ones used by Arbelaez-Cortes et al.

(2012, Zoologica Scripta) for their study on Lepidocolaptes molecular systematics, to run a Maximum Likelihood

phylogenetic analysis (Figure 3). The phylogenetic hypothesis for the genus Lepidocolaptes, using same gene and

sequences (plus the ones for the rest of species), clearly suggests that the

story is more complex. L. albolineatus

might be related to other taxa within the genus though there is a total lack of

resolution at the base of the tree with few robust relationships among taxa.

Each lineage, however, is strongly supported, and layardi shows a well-supported structure with two groups diverging

in 2% for that gene (ND2). Unfortunately, I don´t have information about

localities to explore if there is any geographical signal in such pattern.

Thus, not only the evolutionary history of this group is more complex than we

thought but also the lack of strong support for any phylogenetic relationships

suggests caution before any taxonomic rearrangement is proposed, both for the L. albolineatus species complex and,

particularly, regarding the taxonomic status of both fuscicapillus and layardi.

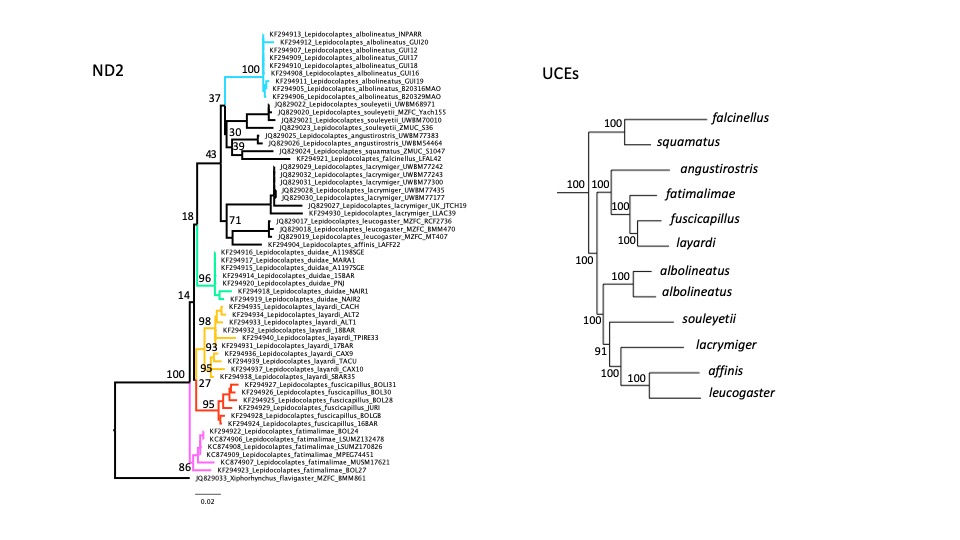

Figure 3. Phylogenetic hypotheses of the genus Lepidocolaptes based on the ND2 gene

(left) and Ultraconserved Elements (UCEs) (Harvey et al. in review; right). The

ND2 hypothesis shows in color each of the five currently recognized taxa for

the L. albolineatus species complex.

Both hypotheses show bootstrap support values based on Maximum Likelihood

analyses.

“Additional but still unpublished

evidence is provided by upcoming suboscine phylogeny by Harvey et al. (in

review) (kindly provided by Mike Harvey). A Maximum Likelihood analysis based

on genomic sequences (UCEs) resulted in a well-resolved phylogeny showing a

polyphyletic L. albolineatus species

complex and suggesting that fuscicapillus

and layardi are sister taxa (Figure

3). This phylogenetic

hypothesis is, by the way, congruent with the previous two-species taxonomy of

this group (albolineatus/fuscicapillus; Cory & Hellmayr 1925,

Catalogue of Birds of the Americas). Though

genomic data are not immune to analytical problems, and this phylogeny only

includes one individual/taxon, at least we have some evidence that fuscicapillus and layardi might be sister taxa. I say “might” because until duidae is not included we are missing an

essential part of the picture.

“In

summary, splitting or lumping fuscicapillus

and layardi into two or just a single

species requires evidence that has not been available to review. A thorough

morphological and vocal analyses should be made available considering the

geographical distribution of each taxa, contact zones (if any), and the potential

geographical variation suggested by the ND2 gene hypothesis (for layardi). Evidence to split the complete

species complex was not thorough or available and, definitely, neither

morphological nor vocal evidence were available to consider these two taxa as

different species. Lumping them back into a single species also requires

evidence. Even when more thorough analyses might eventually show they do not

differ either morphologically or vocally, there is no available information

indicating fuscicapillus and layardi are sister taxa (until duidae is included in phylogenetic

analysis). Additionally, geographical distribution of layardi is congruent with many other Amazonian taxa and a large

genetic divergence (even for just one mitochondrial gene) suggest some sort of

isolation, a pattern that needs to be further explored (looking for potential

causes of the lack of congruence between phenotypic/molecular characters).

Unfortunately, there is no basis to keep the current treatment (i.e., different

species) and lumping them appears to be the available practical solution for

the time being (meaning that a change in taxonomic status is not based on

demonstration they belong to one species or that each lineage does not

represent a single species).”

Comments

solicited from Mario Cohn-Haft: “I don’t really have much of substance to add on this

one based on my personal experience. Basically, I believe that the songs are

virtually indistinguishable between layardi and fuscicapillus. But as I reread the Rodrigues et al. paper and

other evidence called to bear, I am a bit mystified by:

“1)

the rather different looking sonograms between the two in the Rodrigues et al. HBW

paper— I’m curious (but not enough to look them up) to hear those particular

cuts that are graphed. The fuscicapillus

is pictured very faintly even in the strongest parts of the song, so it’s

actually conceivable that the higher peak in layardi notes are actually

made in that cut too, but were filtered out of the figure! And even if not, not sure how different that

would sound. In any case, most cuts of

both spp. sound pretty much identical to me, and in my days of greater activity

in se Amazonia, I never made a distinction between e and w of the Tapajós

birds, but was acutely aware that the 4 quadrants of the Amazon (formed by Negro,

Solimões/Amazon, Madeira) each had different sounding albolineatus types—

i.e., the 4 taxa that everyone’s comfortable with.

“2)

I don’t understand the phrase "the fuscicapillus group is vocally

heterogeneous, with taxa fuscicapillus and layardi being very

distinct vocally, hence suggesting that the polytypic L. albolineatus may

include more than a single species” in the intro of Rodrigues et al. Is that supposed to mean that the two differ

from one another, or that they (as a unit) differ from the rest? It seems like an odd statement to put in the

intro as is, and yet seems to have been picked up in the SACC deliberations

repeatedly as if it were a conclusion.

“It’s

not all that unusual for allospecies to have similar songs, but to differ in

calls or in overall repertoire or in the use of the same repertoire in

different behavioral contexts, so having the same song doesn’t put me off

species distinctiveness automatically. But

it definitely puts up a red flag.

“The

genetic difference, however, seems convincing to me. Yes they’re the most recent split. but the

data, as presented, indicate two nice reciprocally monophyletic groups with a

substantial percent divergence. That

suggests they really are not mixing and that to me is pretty strong evidence of

species status. But similar cases have

proved with subsequent genomic analyses to have lots of gene flow, and

reinterpretation has been necessary. So,

I’d feel a lot more comfortable seeing genomic analyses.

“Sampling

is obviously an important issue. In the

pdf of the article, I can’t make out from the map which localities were

sequenced. I’d sure like to see more

samples and from more strategic localities. Even not being able to distinguish the

different kinds of sample points in the figure, I can see that the potential

contact zone was not well sampled, which seems like an important lacuna for

concluding anything.”

“Finally,

even if the species hold up as distinct, it’s not clear whether the names are

right. The type locality of fuscicapillus,

if I’m reading the map right, is from near to where a contact zone should be

expected. Interestingly, it's also not

far from localities with both (!) fatimalimae and fuscicapillus. That sympatry in itself is interesting (as

mentioned by one of the reviewers of the proposal) and could point either to

sympatry strengthening the species status of the former, or to a zone where potentially

all 3 taxa come into contact and could mix, and where modern analyses should be

focused.

“In

all, rejecting species status for layardi is basically a conservative

move and seems reasonable to me. Not

because there’s strong evidence that it’s not a species, but because there is

still a lack of strong evidence that it is.”

Comments

solicited from Jason Weir: "I have not analyzed the contact zone between Lepidocolaptes [fuscicapillus] layardi and L. [f.] fuscicapillus,

so I can only offer an opinion based on

other contact zones we have analyzed for woodcreepers in this region.

Subspecies of Dendrocincla fuliginosa, Glyphorynchus, as well as Xiphorhynchus

elegans/spixii that come into

contact in this headwater region (Rio Teles Pires) all have very narrow hybrid

zones. I consider them all to be excellent biological species on the basis of

intrinsic postzygotic isolation rather than premating isolation which, based on

vocal divergence is presumably lacking (Dendrocincla

fuliginosa) or weak to moderate

(Xiphorhynchus elegans/spixii), and does not prevent extensive interbreeding

at the contact zone. Each of these species pairs is > 5% GTR-gamma distance

in cytochrome b. In contrast, genomic data I generated for a younger pair

(<4% GTR-gamma distance in cytochrome B) of woodcreeper subspecies from the Xiphorhynchus guttatoides group

demonstrates a very broad hybrid zone here and while they would be considered a

phylogenetic species and have been considered species in the past, it certainly

is not reproductively isolated. Contact

zones are unlikely to occur for all Amazonian taxa and studying those that do

exists takes considerable effort, thus I think it is prudent to extrapolate

evidence we have for the timeline to postzygotic reproductive isolation observed

in currently published hybrid zones to taxa like L. [fuscicapillus] layardi.

Given my hybrid zone data, I suspect

that even in the absence of vocal differentiation, I would recognize

woodcreeper taxa in this region that are > 5% diverged as likely possessing

strong intrinsic postzygotic isolation and I would have no hesitation defining

them as likely representing biological species on this basis. Less than 5%

divergence would require more careful consideration and in the absence of

strong vocal differentiation I would favor taxonomic lumping."

Comments from Pacheco: “YES. I agree that the split of

these two taxa was a misinterpretation and that the available vocal data points

to a very close relationship.”

Comments from Bonaccorso: “YES. The evidence supports

lumping these two taxa into one.”

Comments from Zimmer: “YES, but with reservations about how to

interpret the genetic data and phylogenetic hypothesis, given that, as

correctly pointed out by Jorge, the paper by Rodrigues et al. (2013) does not

resolve the issue of sister relationships among fatimalimae, duidae, fuscicapillus and layardi. The evidence

presented does not unambiguously make the case for splitting fuscicapillus and layardi, but neither does it prove that they should be lumped. We are left in the position of not knowing

what we don’t know. I think the

interpretation that Rodrigues et al. (2013) were focused primarily on

documenting the distinctiveness of fatimalimae

is correct. Remember that there was

confusion in the literature over the subspecific identity of populations from

west of the Madeira – these were attributed by Peters to fuscicapillus, despite the fact that fuscicapillus was described in 1868 from Mato Grosso, east of the

Madeira. The population from the Madeira-Tapajós interfluve, was described in

1919 from Porto Velho, on the east bank of the Madeira in Rondônia, as

subspecies madeirae. Andy Whittaker hit on the fact that birds

from the west bank of the Madeira in Brazil sounded the same as birds on the

rio Javari (Brazil-Peru border) [all purported to be fuscicapillus according to Peters] but distinctly different from

birds from the east bank of the Madeira in Mato Grosso and Rondônia, the

respective type localities for fuscicapillus

and “madeirae”. Songs of birds from those type localities

sounded identical, and it didn’t make sense from the standpoint of biogeography

that there were two identical sounding subspecies occurring on the east bank of

the Madeira in Mato Grosso and Rondônia.

Marantz, et al. (2003 in HBW Volume 8), had apparently reached that

conclusion, and restricted the range of fuscicapillus

to west of the Madeira, seemingly overlooking that the type specimen was from

the east bank. All of this led Whittaker

and his eventual co-authors to conclude that “madeirae” was a junior synonym of fuscicapillus, that it occurred only east of the Madeira, and that

the form with a different voice that was widespread west of the Madeira, lacked

a formal name, and that is the taxon

novum which Rodrigues et al. (2013) described as fatimalimae. I would agree

with Mario Cohn-Haft that the Lepidocolaptes

occurring in the four quadrants of Amazonia:

1) albolineatus in the NE; 2) duidae in the NW; 3) fatimalimae in the SW; and 4) fuscicapillus + layardi in the SE all

sound distinctly different from one another (although there was no adequate

analysis in Rodrigues et al. [2013] to demonstrate this), but that there is no

real distinction between the voices of birds on either side of the Tapajós (fuscicapillus to the west and layardi to the east). Given that, I’m fine with taking a

conservative approach and lumping layardi

into fuscicapillus (which has

priority), despite my aforementioned reservations regarding the genetic data

and associated phylogenetic hypotheses.”

Comments by Lane: “YES. I think Peter has laid out

a strong case for lumping L. layardi into L. fuscicapillus.”