Proposal (872) to South American Classification Committee

Change

species limits in Magnificent Frigatebird Fregata

magnificens

Background: The frigatebirds, with

their great plumage similarity among comparable ages and sexes, as well as the

very different immature stages over a period of several years, have long been

the subjects of taxonomic confusion. Few avian groups with so few species can

have had so many words, photos, and illustrations dedicated solely (and often

futilely) to their identification. Nevertheless, many early authors thought a

single species inhabited pan-tropical oceans, and though several taxa had by

then been named, only two species were recognized in the Catalogue of the Birds in the British Museum (Ogilvie-Grant 1898).

Two forms, a larger and smaller one, were recognized to occur on the Galapagos

by Ridgway (1897), but Rothschild and Hartert (1899) believed they intergraded

completely and therefore were not worthy even of subspecies status, until

Mathews (1914), on the basis of study of British Museum specimens, recognized

that two distinct frigatebird taxa breed in the Galapagos Islands. Among the

several new Fregata taxa he described

from around the tropics was Fregata minor

magnificens Mathews, 1914, which he considered a subspecies of Great

Frigatebird F. minor (Mathews 1914,

1915). Rothschild (1917) then reconsidered his earlier position and clarified

that magnificens should be treated as

a separate species, not a subspecies of minor.

Since then, magnificens and minor have been generally recognized as

full species that are mostly allopatric except on the Galapagos, and subsequent

authors have generally recognized five species of frigatebird (e.g., Lowe

1924). Two or three subspecies are often recognized for F. magnificens, the nominate in the Galapagos, rothschildi in most of the rest of the range, and lowei for the

highly isolated population of the Cape Verde Islands (Swarth 1933, AOU 1957,

del Hoyo and Collar 2014). In many other treatments, including most recent

ones, however, magnificens is treated

as monotypic (AOU 1931, Hellmayr and Conover 1948, Dorst and Mougin 1979,

Dickinson and Remsen 2013, Clements et al. 2019, Gill et al. 2020). The AOU

(e.g., AOU 1889, 1895, 1910) long recognized just a single regional species,

now known as the Magnificent Frigatebird F.

magnificens, but three species are now included in the expanded NACC region

(AOU 1983, Chesser et al. 2019), and four in the SACC region (Remsen et al.

2020).

New information: Hailer et al. (2011)

found that over most of their New World range, F. magnificens has high levels of gene flow, including across the

Isthmus of Panama, which usually serves as a barrier to other taxa of seabirds.

However, despite predictions based on the extraordinary vagility of

frigatebirds, the Galapagos population was found to be strongly genetically

differentiated from the other populations (see screenshots below of Figs. 2 and

3 from Hailer et al. 2011). The Galapagos population must therefore have been

genetically isolated for at least a few hundred thousand years (Hailer et al.

2011).

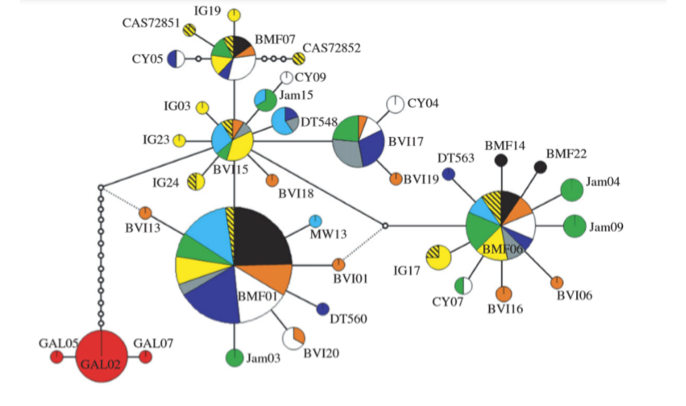

Fig.

2 from Hailer et al. (2011). Parsimony network of mtDNA sequences, Galapagos in

red.

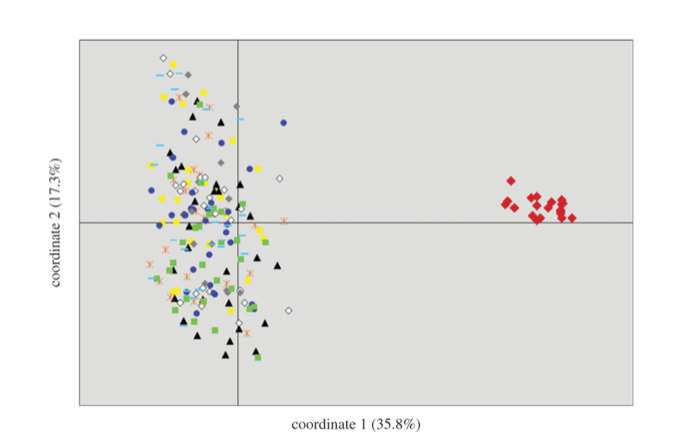

Fig.

3 from Hailer et al. (2011). PCA of microsatellite genotypes, Galapagos in red.

Further,

in a study of population structure primarily of Atlantic and Caribbean

populations, Nuss et al. (2016) found that, although

Brazilian and Caribbean populations were genetically isolated from one another,

the geographically interposed population from French Guiana (Grand Connétable) shared haplotypes with both regions. As shown

by Hailer et al. (2011), the Galapagos population had highly divergent

haplotypes (see screenshot of Fig. 2 from Nuss et al.

2016, below). In a study of Mexican F.

magnificens populations, Rocha-Olivares and González-Jaramillo (2014) found

lower levels of gene flow between colonies and especially between ocean basins

than did Hailer et al. (2011), and offered explanations for this discrepancy,

including more individuals sampled, more peripheral sampling locations, and

greater geographical distances in their more recent study.

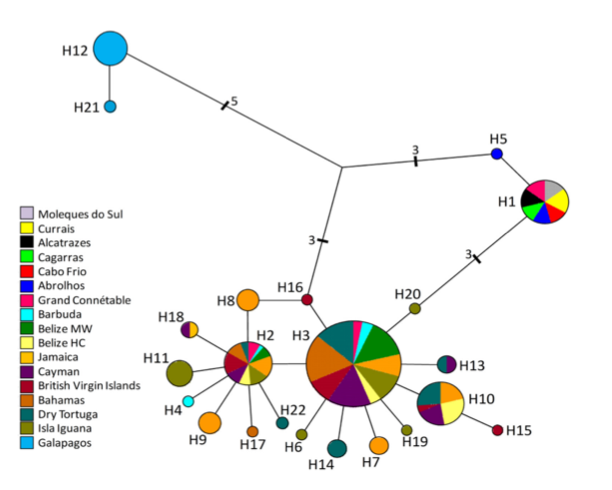

Fig.

2 from Nuss et al. (2016). Median-joining network,

mtDNA haplotypes.

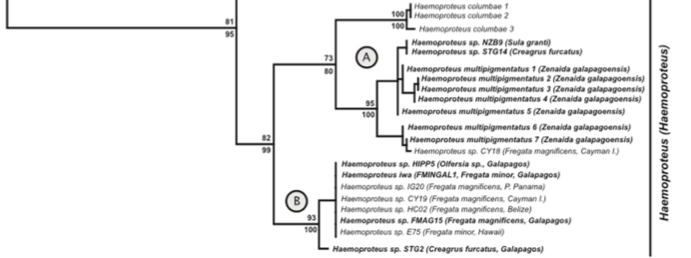

Despite

the genetic divergence of the Galapagos F.

magnificens population, the same

haemoprotean parasite, Haemoproteus iwo,

occurs in F. minor as well as F. m. magnificens from Galapagos and

multiple localities within the range of F.

m. rothschildi (Clade B of Fig. 1 in Levin et al. 2011, see screenshot

below). This non-congruence in divergence levels between parasite and host

suggests that transfer by hippoboscid flies (e.g. Olfersia) may take place between non-breeding frigatebirds at

communal roosts, as well as at colonies. There is some movement of non-breeding

Galapagos Magnificent Frigatebirds to Central America, where dead or emaciated

birds banded in the Galapagos have been recovered (according to a pers. comm.

in Hailer et al. 2011, details not provided). The haemoprotean parasite’s lack

of divergence may be considered confirmatory of the mixing of frigatebird

populations outside of the breeding colonies.

Fig.

1 of Levin et al. (2011). Relevant part of ML tree of haemosporidian cytb.

Several

external measurements taken of Magnificent Frigatebirds (5 of each sex from the

Galapagos, 11 and 16 from non-Galapagos specimens) corroborated that, in wing

and inner and outer tail dimensions, and culmen of females, the Galapagos

population is significantly larger (Hailer et al. 2011). My informal inspection

of many eBird photos (selecting only those in non-foreshortened view) seems to

confirm that the tail is relatively longer in Galapagos birds. Otherwise, I

cannot see any plumage or soft part color differences and am unaware of any

that have been reliably suggested.

The

authors of the above studies are in general agreement that sex-biased dispersal

(with males exhibiting site fidelity) and female mate choice for the complex

male mating rituals of frigatebirds is most likely to explain the patterns

seen, especially the genetic distinctness of the Galapagos population. However,

none presented or referenced any data on differences in e.g. display or

vocalizations. I located only one online recording from the Galapagos, which

did not prove useful, though there must be recordings in compilations and

private collections. It seems apparent that isolating mechanisms beyond simple

geographical isolation must be operating, otherwise the Galapagos population

would be experiencing gene flow with mainland birds.

The

Cape Verde population named F. m. lowei has not been included in the above studies, but

as of 2012 only one bird of each sex appeared to be present at the former

colony (Suarez et al. 2012), due to persecution. These authors indicated their

intention to conduct genetic and mensural analysis of the distinctiveness of

this virtually extinct and highly isolated population.

Note

that Olson (2017) has recently espoused treatment of Lesser Frigatebird Fregata ariel as two species, as the

form trinitatis now restricted to

Trindade Island and known from St. Helena by fossils has different proportions

(stouter wing and bill) and putative plumage differences in immature stages.

There are parallels with the case of Magnificent Frigatebird, but genetic data

that would bolster the case for specific status of trinitatis appear to be lacking. A proposal (SACC#768, https://www.museum.lsu.edu/~Remsen/SACCprop768.htm) to split trinitatis was rejected in favor of

further evidence.

Effect on AOS-NACC and

SACC areas: If

split, the Galapagos population would retain the specific epithet magnificens, and thus the widespread

frigatebird of the Americas would become Fregata

rothschildi. There would also obviously be English name issues. In addition,

there are evidently records of Galapagos birds from somewhere in Central

America, so details would have to be located for the NACC area, and a new

species added to both regional checklists.

It

should be added that, even if this proposal does not pass, this species clearly

should not be considered monotypic by global checklist authorities.

Recommendations:

Although

it would be ideal if there were behavioral studies and analyses of the

courtship display vocalization repertoire that established the existence of

premating isolating mechanisms between Galapagos and mainland birds, these are

not available to my knowledge. What we do know is that there is little if any

gene flow, despite movement of at least some non-breeding individuals from the

Galapagos to the mainland, which I take to be prima facie evidence that

speciation has occurred. Please vote separately for each option.

A.

A YES vote for (A) would be to split F.

m. magnificens, with the resultant daughter species F. magnificens of the Galapagos and F. rothschildi in the remainder of the range (whether or not lowei of Cape

Verde is recognized).

If

(A) passes, English name issues arise. Obviously, Magnificent Frigatebird could

be retained for the vastly more widespread rothschildi

but it would no doubt cause confusion, given the retention of magnificens by the Galapagos form.

(Consider though that we have all learned to live with Great Frigatebird being Fregata minor, while Lesser is F. ariel.) Another option might be

American Frigatebird, but of course Galapagos are part of the Americas, and in

fact American Man-O-War Bird was used by Hellmayr and Conover (1948) for their

monotypic, widespread F. magnificens

(including the Galapagos population). I recommend retention of Magnificent

though as being the least disruptive option.

B.

A YES vote for (B) would be to retain Magnificent Frigatebird for Fregata rothschildi.

Galapagos

Frigatebird would be my suggestion for F.

magnificens s.s.

C. A YES vote for (C) would be for Galapagos

Frigatebird F. magnificens.

Literature Cited:

American

Ornithologists’ Union (1889). Check-list of North American Birds. First Edition,

Abridged. American Ornithologists’ Union.

American

Ornithologists’ Union (1895). Check-list of North American Birds. Second

Edition, Revised. American Ornithologists’ Union.

American

Ornithologists’ Union (1910). Check-list of North American Birds. Third

Edition. American Ornithologists’ Union.

American

Ornithologists’ Union (1931). Check-list of North American Birds. Fourth

Edition. American Ornithologists’ Union.

American

Ornithologists’ Union (1957). Check-list of North American Birds. Fifth

Edition. American Ornithologists’ Union.

American

Ornithologists’ Union (1983). Check-list of North American Birds. Sixth

Edition. American Ornithologists’ Union.

Chesser, R. T., K. J. Burns, C. Cicero, J. L. Dunn, A. W. Kratter, I. J.

Lovette, P. C. Rasmussen, J. V. Remsen, Jr., D. F. Stotz, and K. Winker (2019).

Check-list of North American Birds (online). American Ornithological Society. http://checklist.americanornithology.org/taxa

Clements, J. F., T. S. Schulenberg, M. J. Iliff,

S. M. Billerman, T. A. Fredericks, B. L. Sullivan, and C. L. Wood (2019). The

eBird/Clements Checklist of Birds of the World: v2019. Downloaded from https://www.birds.cornell.edu/clementschecklist/download/

del Hoyo, J., and N. J.

Collar (2016). HBW and BirdLife International Illustrated Checklist of the

Birds of the World. Volume 2: Passerines. Lynx Edicions, Barcelona.

Dorst, J., and J.-L.

Mougin (1979). Order Pelecaniformes.

Pp. 155–193 in: Mayr, E. and G. W. Cottrell (Editors). Check-list of the Birds

of the World. Volume 1, Ed. 2. Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA.

Dickinson, E. C., and

J. V. Remsen, Jr. (Editors) (2013). The Howard and Moore Complete Checklist of

the Birds of the World. 4th edition. Volume One. Non-passerines.

Aves Press Ltd., Eastbourne, UK.

Gill, F., D. Donsker,

and P. C. Rasmussen (Editors) (2020). IOC World Bird List (v 10.2). DOI

10.14344/IOC.ML.10.2. http://www.worldbirdnames.org/

Hailer, F., E. A.

Schreiber, J. M. Miller, I. I. Levin, P. G. Parker, R. T. Chesser, and R. C.

Fleischer (2011). Long-term isolation of a highly mobile seabird on the

Galapagos. Proceedings of the Royal Society B 278:817–825.

Hellmayr, C. E., and B.

Conover (1948). Catalogue of Birds of the Americas and Adjacent Islands. Vol.

13, Part I, No. 2. Publication 615, Field Museum of Natural History, Chicago.

Levin, I. I., G.

Valkiunas, D. Santiago-Alarcon, L. L. Cruz, Tatjana A. Iezhova, S. L. O’Brien,

F. Hailer, D. Dearborn, E. A. Schreiber, R. C. Fleischer, R. E. Ricklefs, and

P. G. Parker (2011). Hippoboscid-transmitted Haemoproteus parasites (Haemosporida) infect Galapagos pelecaniform

birds: evidence from molecular and morphological studies, with a description of

Haemoproteus iwa. International

Journal for Parasitology 41:1019–1027.

Lopez-Suarez, P., C. Hazevoet, and L. Palma (2012). Has the Magnificent

Frigatebird Fregata magnificens in

the Cape Verde Islands reached the end of the road? Zoologia Caboverdiana

3:82–86.

Lowe, P. R. (1924).

Some notes on the Fregatidae. Novitates Zoologicae 31:299–313.

Mathews, G. M. (1914).

On the species and subspecies of the genus Fregata.

The Austral Avian Record 2:117–121.

Mathews, G. M. (1915).

The Birds of Australia. Volume 4. Witherby, London.

Nuss, A., C. J. Carlos, I.

B. Moreno, and N. J. R. Fagundes (2016). Population genetic structure of the

Magnificent Frigatebird Fregata

magnificens (Aves, Suliformes) breeding colonies in the Western Atlantic

Ocean. PLoS ONE 11:e0149834.

Ogilvie-Grant, W. R. (1898). Catalogue of the Birds in the British

Museum. Vol. 26. Trustees, London.

Olson, S. L. (2017) Species rank for the critically endangered Atlantic

Lesser Frigatebird (Fregata trinitatis).

Wilson Journal of Ornithology 129:661–675.

Remsen, J. V., Jr., J. I. Areta, C. D. Cadena, S. Claramunt, A.

Jaramillo, J. F. Pacheco, J. Perez Emán, M. B. Robbins, F. G. Stiles D. F.

Stotz, and K. J. Zimmer (Version 11 February 2020). A Classification of the

Bird Species of South America. American Ornithological Society.

http://www.museum.lsu.edu/~Remsen/SACCBaseline.htm

Ridgway, R. (1897). Birds of the Galapagos Archipelago. No. 1116.

Proceedings of the United States National Museum 19:459–670.

Rocha-Olivares, A. and

M. González-Jaramillo (2014). Population genetic structure of Mexican

Magnificent Frigatebirds: an integrative analysis of the influence of

reproductive behavior and sex-biased dispersal. Revista Mexicana de

Biodiversidad 85:532–545.

Rothschild, W. (1917). On the genus Fregata.

Novitates Zoologicae 22:145–146.

Swarth, H. S. (1933).

Frigate-birds of the west American coast. Condor 35: 148–150.

Pamela

C. Rasmussen, August 2020

Comments

from Areta:

“NO. The fact that there are some minor morphological measurements and an

unimpressive 0.88% of genetic divergence seems not enough to split magnificens from rothschildi. It certainly is

interesting that there is no apparent gene flow between Panamanian Pacific

populations and the Galapagos, which one might well prima facie expect based on

the high vagility of frigatebirds. But

the lack of gene flow does not necessarily equates with the existence of a

separate species. The connectivity seems

much better in the Caribbean than on the Pacific, so the patterns of flow on

the Caribbean are not that surprising. I would like to see what happens when

populations breeding further south along the Pacific (e.g., in Ecuador) are

sampled. Will they show evidence of gene flow? Will they reduce the level of

genetic differentiation thought to exist between continental and Galapagos

populations?”

Comments

from Stiles:

“NO, for now. The complete distinction in haplotypes clearly indicates no

interbreeding between the Galápagos and all mainland populations studied so

far. Given that magnificens s. l.

breeds on islands along the Pacific coast at least from Costa Rica south to

Peru, genetic data from these populations would seem to be the missing piece in

the puzzle. Although I think that Pam is probably right, I would prefer to

await data from these populations. (At least in Costa Rica, occasional

individuals of Fregata do cross over

the country between the Caribbean and the Pacific).”

Comments

from Claramunt:

“NO. Very suggestive of species status but I agree

with Nacho that populations along the coast of Ecuador should be evaluated

before making such a traumatic change.

Comments

from Robbins:

“NO. I agree that Pacific populations in

Central and northern South America should be sampled to provide a better

picture before making a change.”

Comments from Zimmer: “NO

for now. As others have already

expressed, I think we need more sampling from more sites along the Pacific

Coast of the Americas to sort out the nature of gene flow and ascertain what

the bottlenecks are. Meanwhile, some

concrete evidence of potential premating isolating mechanisms (such as in

display/courtship vocalizations) between Galapagos birds and other populations

of magnificens, would be particularly

helpful.”

Comments from Remsen: “NO. Divergence in mtDNA is insufficient evidence

for species rank. Nor does lack of gene

flow between allopatric BREEDING populations, in my opinion, even in something

as vagile as Fregata; parapatric or sympatric, yes, then lack of gene

flow is prima facie evidence of speciation.

Nor does slightly larger body size.

Even taken together, the evidence is insufficient. Further, as pointed out by several above, the

geographic sampling scheme is inadequate.

The “bar” for species limits is pretty low in Fregata, but I

don’t see any evidence that the bar has been reached in this case.”

Comments

from Pacheco:

“NO. The suggestion of Nacho seems reasonable to me

that “key” populations along the coast of Ecuador should be assessed before

making a major change.”

Comments from Lane: “NO. As others have pointed out,

I think there are too many unsampled populations to put this case to rest.”

Comments from Jaramillo: “NO – An analysis of display and voice

needs to be done, given that flying around with a big red inflatable pouch

while making vibrating sounds is a pretty major and obvious display that these

birds use to secure a mate. I think that there should be some differences in

display once analyzed if the Galapagos birds are a different species. Note that

they are sympatric with Great Frigatebirds on some of the islands, so there

will be a “standard” for difference in displays in two clear-cut species

breeding side by side.

“Another thing to consider is that Magnificents are a species that is a nearshore marine bird.

They are not truly pelagic as Great Frigates and other species in the genus. So

it is possible that while in our heads we may think of frigatebirds as being

highly mobile, these birds may be resident and may never move farther away than

100 km from the islands. So this alone could create the lack of gene flow. Most

other populations are somewhat near adjacent populations, and island groups are

not nearly as isolated as the Galapagos.”

Comments from Bonaccorso: “NO. Although I think that the

mitochondrial DNA and microsatellite data are very convincing. That level of

genetic divergence in a population of birds from Galapagos and, especially, in

vagile organisms as Fregata, seems like very good evidence of

reproductive isolation. However, I think this proposal should include a

systematic comparison of measurements and, more importantly, courtship

vocalizations between the Galapagos population and other populations.”