Proposal (873) to South American Classification Committee

Modify

species limits in Forpus: (A) Treat Forpus crassirostris as a separate species from F. xanthopterygius, and (B) Treat Forpus spengeli as a separate species from F. passerinus

Background: The distinctive,

morphologically homogeneous Parrotlet genus Forpus

is usually treated as being comprised of seven species (e.g. Forshaw 1973,

Sibley and Monroe 1993, Dickinson 2003, Dickinson and Remsen 2013, Clements et

al. 2019), although Peters (1937) only recognized five. Most are allopatric,

with only one species (F. modestus)

overlapping broadly geographically with other species. All are sexually dichromatic,

and most are polytypic. Not surprisingly, species limits have long been

contentious, and nomenclatural issues have caused further confusion (e.g.,

Collar 1997, Juniper and Parr 1998, Whitney and Pacheco 1999, SACC proposal #4).

The most widespread species as currently

recognized by most authorities is Blue-winged Parrotlet Forpus xanthopterygius. Its member taxa were often treated as three

different species: F. xanthopterygius

(= vivida); F. crassirostris; and F.

spengeli (e.g. Ridgway 1916, Cory 1918), while others (e.g., Hellmayr 1907,

Peters 1937) considered them all races of Green-rumped Parrotlet Forpus passerinus. Gyldenstolpe (1945,

not seen), however, showed that crassirostris

and passerinus are narrowly

parapatric in western Brazil, without evidence of intergradation (Juniper and

Parr 1998, Whitney and Pacheco 1999), and on this basis and their obviously

different rump colors, he and subsequent authors have mostly treated them as

separate species (although with crassirostris

as a subspecies of xanthopterygius).

Collar (1997) and Juniper and Parr (1998) have suggested that spengeli may be more closely related to

or conspecific with the broadly allopatric Mexican Parrotlet Forpus cyanopygius. For a more in-depth

summary of the taxonomic history of F.

xanthopterygius, see Bocalini and

Silveira (2015).

New information:

Smith

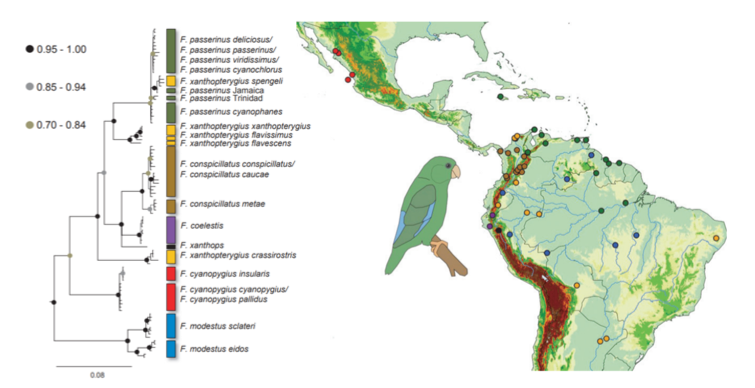

et al. (2013), in a phylogenetic analysis of mtDNA and nuclear loci of all

species and most subspecies of Forpus,

found that spengeli of northern

coastal Colombia is embedded (on the basis of mtDNA only, no nuclear data being

available) within F. passerinus

rather than F. xanthopterygius (see

their Fig. 1 below). Thus, although Dickinson (2003) had treated spengeli as a subspecies of xanthopterygius, Dickinson and Remsen

(2013) treated it as a race of passerinus,

and Remsen et al. (2020) provide the rationale. However, this treatment does

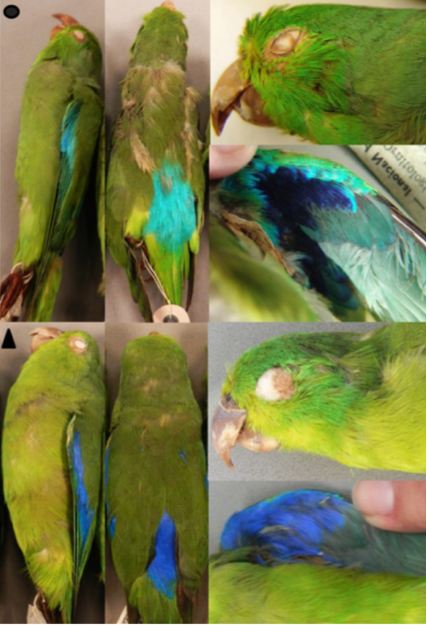

not address the seemingly considerable morphological disparity between spengeli and other subspecies of passerinus, especially F. p. cyanophanes of arid north-eastern

Colombia (between the Santa Marta and Perijá mountains). These two appear to be

essentially parapatric, but cyanophanes

has conspicuous, extensive violet-blue on upper- and underwing coverts, quite

unlike those of spengeli (see photo below),

which also has a brilliant turquoise rump (vs. green in cyanophanes). In addition, this change to species attribution of spengeli appears to have been made

solely on the basis of mtDNA.

Smith

et al. (2013) also found evidence that crassirostris

is sister to the clade comprised of most Forpus

taxa, except modestus and cyanopygius. This result was strongly

supported on the mtDNA tree but not well supported in the nuclear DNA and

species tree.

Fig.

1 of Smith et al., mtDNA

Fig.

3 of Smith et al., species tree

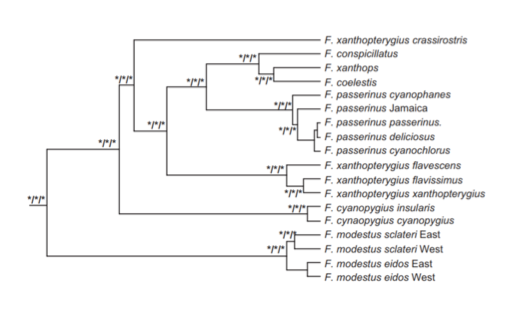

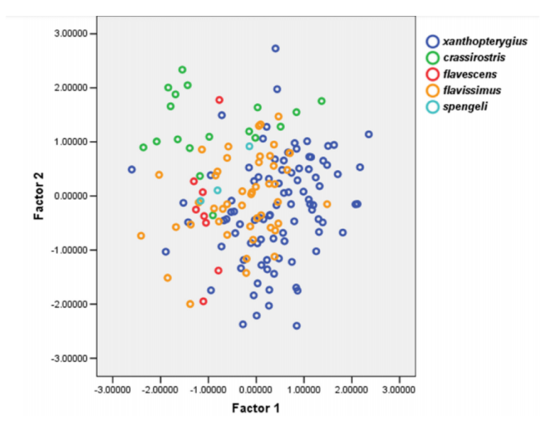

Bocalini

and Silveira (2015) analyzed geographic variation in morphology of 518

specimens of the F. xanthopterygius

complex, and concluded that spengeli

should be considered a distinct species (see their Fig. 1 below). However,

their study did not evaluate the possibility that spengeli may be conspecific with F. passerinus. They also considered that crassirostris (along with the other subspecies of xanthopterygius traditionally

recognized) is not diagnosable phenotypically and should thus be considered a

synonym of F. xanthopterygius, which

they treat as monotypic (Bocalini and Silveira 2015). However, they did confirm

that crassirostris is smaller overall

than the nominate (with overlap, see their Fig. 3 below), which they attribute

to Bergmann’s Rule, given its more northerly (Southern Hemisphere) range.

However, they did not place this finding in context of other ecogeographic

studies, and it does not seem clear from the literature that Bergmann’s Rule

applies in any consistent way to fauna of tropical and subtropical

lowlands. Also, Bocalini and Silveira

(2015) did not address the other morphological differences summarized in Cooper

(1973): “like xanthopterygius, but

all blue markings paler; primary-coverts pale greyish violet-blue contrasting

with darker violet-blue secondary-coverts; upper mandible compressed laterally

at the centre”, or its relatively large bill (Hellmayr 1907) so their study

does not negate the putative existence of these differences.

Fig.

1 (part) from Bocalini and Silveira (2015); spengeli

above, xanthopterygius below

Fig.

3 from Bocalini and Silveira (2015); Factor 1 is a general size axis and Factor

2 is mainly influenced by culmen length.

Donegan

et al. (2016) reexamined the question of whether spengeli should be split from xanthopterygius

under the view that the best yardstick is whether differences exceed those

between sympatric species of the same genus. From examination of AMNH specimens

(see their Figs. 3-4, below) they determined that differences between spengeli and xanthopterygius were substantial, especially compared to those

between F. modestus and F. xanthopterygius, and in addition

noted that spengeli is found in drier

habitat. They also compared spengeli

with F. passerinus viridissimus at AMNH (see their Fig. 5

below) and noted further plumage distinctions, and they discussed the potential

for a contact zone between viridissimus

and spengeli and the lack of clear

evidence for intergradation (Donegan et al. 2016).

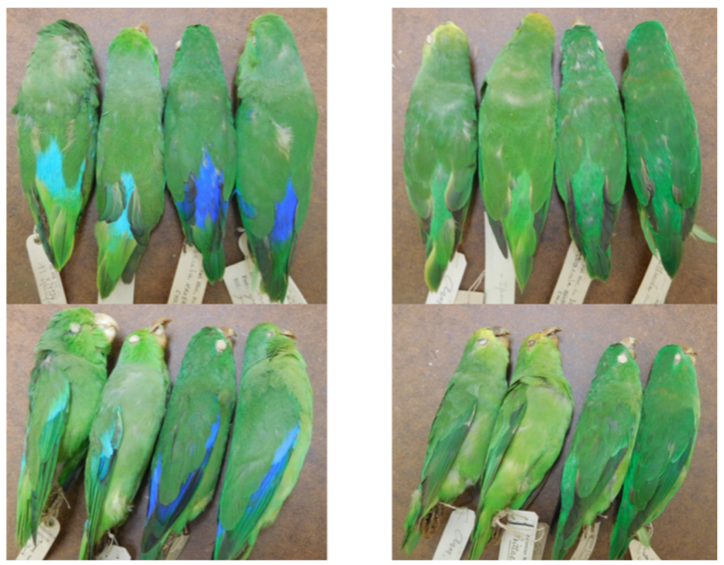

Fig.

5 from Donegan et al. (2016). In each, the two specimens on the left are F. passerinus viridissimus and the two

on the right are spengeli.

In

summary, although mtDNA places spengeli

within the F. passerinus clade, and

it clearly does not belong with F.

xanthopterygius, it is as distinctive morphologically as most other Forpus treated as species and it appears

to be parapatric, without reported intergradation to my knowledge, with the

quite different-looking F. passerinus

cyanophanes. Although SACC (Remsen et al. 2020) treats spengeli as a subspecies of passerinus,

Clements et al. (2019) maintain it within xanthopterygius,

and del Hoyo and Collar (2014) and Gill and Donsker (2015) consider spengeli a full species, the aptly

descriptive Turquoise-winged Parrotlet.

And,

although crassirostris (including the

sometimes recognized ollalai of

east-central Amazonas) is only subtly distinct in plumage, the mtDNA tree

places it as sister to most other Forpus (except

modestus and cyanopygius, and it differs from other taxa of F. xanthopterygius in its smaller size but relatively larger bill,

but with a reportedly laterally compressed culmen. Although other authors

maintain crassirostris within xanthopterygius, Gill and Donsker (2015)

consider it a full species (as was done by Ridgway 1916 and Cory 1918),

adopting the common name Large-billed Parrotlet from Cory (1918) for crassirostris.

Another

option would be to reunite all these taxa (xanthopterygius

s.l. + passerinus s.l.) under Forpus passerinus,

as in Hellmayr (1907) and Peters (1937), but that is argued against by the

greater morphological disparity of such a grouping relative to other Forpus species, the greater branch

length on the mtDNA tree than between the undisputed species in the coelestis + xanthops and conspicillatus clade,

and the two zones of apparent parapatry (between spengeli and cyanophanes

in northeastern Colombia and between crassirostris

and Forpus passerinus deliciosus in

Amazonas).

Effect on AOS-SACC

area:

This

proposal would elevate up to two subspecies endemic to South America to species

status.

Voting:

A YES vote on (A) would be to split crassirostris from F. passerinus.

IF (A)

passes, a YES vote on (B1) would be to adopt the English name Large-billed

Parrotlet for F. crassirostris.

IF (A) passes, a YES

vote on (B2) would be to retain the English name Blue-winged Parrotlet for the

more widely distributed F.

xanthopterygius s.s.

A YES vote on (C) would be to split spengeli from F. xanthopterygius.

If (A) passes, a YES vote on (D1) would be to

adopt the English name Turquoise-winged Parrotlet for F. spengeli.

If (A) passes, a YES

vote on (D2) would be to retain the English name Green-rumped Parrotlet for the

much more widely distributed F.

passerinus s.s.

Literature Cited:

Bocalini, F., and L. F. Silveira (2015). Morphological variability and

taxonomy of the Blue-winged Parrotlet Forpus

xanthopterygius (Psittacidae). Revista Brasileira de Ornitologia

23(1):64–75.

Clements, J. F., T. S. Schulenberg, M. J. Iliff,

S. M. Billerman, T. A. Fredericks, B. L. Sullivan, and C. L. Wood (2019). The

eBird/Clements Checklist of Birds of the World: v2019. Downloaded from https://www.birds.cornell.edu/clementschecklist/download/

Collar, N. (1997).

Family Psittacidae (Parrots). In del Hoyo, J., A. Elliot, and J. Sargatal

(Editors). Handbook of the Birds of the World. Volume 4. Sandgrouse to Cuckoos.

Lynx Edicions, Barcelona.

Cory, C. B. (1918).

Catalogue of Birds of the Americas. Part 2 No. 1. Field Museum of Natural

History Zoological Series 13(197).

del Hoyo, J., and N. J.

Collar (2014). HBW and BirdLife International Illustrated Checklist of the

Birds of the World. Volume 1: Non-passerines. Lynx Edicions, Barcelona.

Dickinson, E. C.

(Editor) (2003). The Howard and Moore Complete Checklist of the Birds of the World.

Revised and enlarged 3rd edition. Christopher Helm, London.

Dickinson, E. C., and

J. V. Remsen, Jr. (Editors) (2013). The Howard and Moore Complete Checklist of

the Birds of the World. 4th edition. Volume One. Non-passerines.

Aves Press Ltd., Eastbourne, UK.

Donegan, T., J. C.

Verhelst, T. Ellery, O. Cortés-Herrera, and P. Salaman (2016). Revision of the

status of bird species occurring or reported in Colombia 2016 and assessment of

BirdLife International’s new parrot taxonomy. Conservación Colombiana No.

24:12-36.

Forshaw, W. T. (1973).

Parrots of the World. Doubleday, Garden City, New York.

Gill, F., and D.

Donsker (Editors) (2015). IOC World Bird List (v 5.3). http://www.worldbirdnames.org/

Gyldenstolpe, N.

(1945). The bird fauna of Rio Juruá in Western Brazil. Kongliga Svenska

Vetenskaps-Akademeins Handlingar 22(3):1-338.

Hellmayr, C. E. (1907).

Another contribution to the ornithology of the lower Amazons. Novitates

Zoologicae 14:1-39.

Juniper, T., and M.

Parr (1998). Parrots. A Guide to the Parrots of the World. Pica Press, Sussex,

UK.

Peters, J. L. (1937). Check-list of the Birds of the World. Volume

3. Harvard University Press, Cambridge, Massachusetts.

Remsen, J. V., Jr., J. I. Areta, C. D. Cadena, S. Claramunt, A.

Jaramillo, J. F. Pacheco, J. Perez Emán, M. B. Robbins, F. G. Stiles D. F.

Stotz, and K. J. Zimmer (Version 11 February 2020). A Classification of the

Bird Species of South America. American Ornithological Society. http://www.museum.lsu.edu/~Remsen/SACCBaseline.htm

Ridgway, R. (1916). The

birds of North and Middle America. Bulletin of the United States National

Museum No. 50 Part 8.

Sibley, C. G., and B.

L. Monroe, Jr. (1993). A World Checklist of Birds. Yale University Press, New

Haven, Connecticut.

Smith, B. T., C. C. Ribas, B. M. Whitney, B. E. Hernández-Baños, and J.

Klicka (2013). Identifying biases at different spatial and temporal scales of

diversification: a case study in the Neotropical parrotlet genus Forpus. Molecular Ecology

22:483–494.

Whitney, B. M., and J. E. Pacheco (1999). The valid name for Blue-winged

Parrotlet and designation of the lectotype of Psittaculus xanthopterygius Spix, 1824. Bulletin of the British

Ornithologists’ Club 119:211-214.

Pamela

C. Rasmussen, August 2020

Comments

from Areta:

“A) YES. To be consistent with recognition of other species in Forpus.

The relatively deep divergence of crassirostris

and the lack of monophyly this implies for xanthopterygius

makes this the only reasonable alternative at hand without a major overhaul of

taxonomy in Forpus.

“B)

NO. Smith et al (2012) found that spengeli

is a taxon more closely related to (and embedded within) passerinus as currently delineated. Given the minor genetic

differentiation, the not really impressive plumage differences, and the

difficulty in understanding what the plumage differences might mean in a genus

characterized by complicated plumage variation that does not clearly correspond

with phylogenetic relationships, I prefer to leave spengeli within passerinus.”

Comments

from Stiles:

“YES to A: recognizing crassirostris as

a species. YES to B1 and B2 (E-names). C: YES to this split as well, and YES to

B1 and B2 (E-names). The genetics, morphology and distributions fit well.”

Comments

from Robbins:

“A) YES, to recognizing crassirostris as a species based on the Smith et

al. genetic data. C) NO, to spengeli as a species, as I agree with

comments by Nacho.”

Comments

from Zimmer:

“(A) YES, using the

“yardstick” of differentiation seen in other recognized species of Forpus.

“(B1) YES for adopting

the English name of Large-billed Parrotlet for F. crassirostris.

“(B2) YES for retaining

the familiar English name of Blue-winged Parrotlet for the more widely

distributed F. xanthopterygius sensu stricto.

“(C) I’m a little confused here, because I thought

the molecular data showed spengeli to

be embedded within passerinus, which

is where I thought we currently treat it.

Yet, in the Voting instructions at the end of the Proposal, it is stated

that a “YES vote on (C) would be to split spengeli from F. xanthopterygius” (bold-face mine). I can only assume this is an error, since the

title of the Proposal reads “(B) Treat Forpus

spengeli as a separate species from F. passerinus.” Going with that assumption, then we would

appear to have a conflict between the molecular data and what are, to me,

fairly clear plumage distinctions that are at least on a par with the

distinctions between other recognized species of Forpus. Given that conflict, I am tentatively

persuaded by the described parapatry between spengeli and cyanophanes

without evidence of intergradation. So,

a tentative “YES” for splitting spengeli

from passerinus, and treating it as a

distinct species.

“(D1) YES to

establishing Turquoise-winged Parrotlet as the English name for a split spengeli.

“(D2) YES” for

retaining Green-rumped Parrotlet for the widespread F. passerinus.”

Comments

from Pacheco:

“As Kevin has already warned, the proposal's title

and its recommendations are not perfectly aligned. Having said that, my votes

are:

“A – NO, tentatively. Although there is evidence by mtDNA that crassirostris

is clearly distinct, I am concerned about the alleged lack of diagnosability

pointed out by Bocalini and Silveira (2015).

“C – YES, tentatively. Clarifying that this “yes” is for splitting

spengeli from passerinus, and treating it as a separate species.”

Comments from Claramunt:

“A. YES. Given the conservative plumage of this genus, I think that

the mtDNA evidence is compelling.

“C. YES. I think there is a chance that the lack of reciprocally

monophyly between spengeli and passerinus is artifactual. Further

analyses are needed, but I give spengeli the benefit of the doubt.”

Comments from Lane:

“A) YES. I should

note that Vitor Piacentini sent me a private email that made me hesitate by

suggesting that two forms of Forpus might be involved within the Amazon

of northern Peru, based on orbital skin color and iris color in the photos

available in Macaulay Library. I am not sure if these character states are

necessarily taxon-driven but rather may be age-driven (or perhaps even just effects

of lighting, etc.). If the characters are taxon driven--meaning there could be

two "xanthopterygius-types" in northern Peru, then we'd have

to be very careful we apply the name "crassirostris"

correctly! But after reviewing photos on Macaulay again, I am thinking that

this may be entirely either age-driven or lighting effects, and not taxonomic

characters at all (in addition, I would expect there to be vocal characters

that would offset with two potentially sympatric Forpus, but I am

unaware of any beyond those between F. xanthopterygius/crassirostris and

F. modestus). So I will say YES, but wonder if there may be a more

complicated issue in western Amazonia?

“B1) YES to

accepting Large-billed Parrotlet as English name for F. crassirostris.

“B2) NO to

retaining "Blue-winged Parrotlet" for restricted F. xanthopterygius.

Even though Smith and all showed that crassirostris is not sister to xanthopterygius,

it occupies a huge portion of the range (I think? This is not really clear to

me. I guess it is the western Amazonian form, if not more widespread?) of that

species sensu lato. So I think it would be confusing to retain that name for

the sensu stricto version. Thus, a new name would be necessary by my

estimation. Hellmayr isn't very helpful in providing a reasonable name for the

form sensu stricto, so a novel name may be the best move. I would propose

something like "Cerrado Parrotlet", but that's just a first attempt,

and without fully understanding where the break between the two species occurs,

and their preferred habitats.

“C) YES

“D1) YES to

accepting Turquoise-winged Parrotlet as English name for F. spengeli.”

“D2) YES to retaining Green-rumped Parrotlet for restricted F.

passerinus.”

Comments from Remsen:

“A) YES, reluctantly. I suppose the genetic data are solid (N=4 crassirostris

samples; nDNA shows same basic pattern as mtDNA), but those same data found spengeli

embedded in passerinus – so something is fishy. But I share Fernando’s concern. Contrary to statements in the proposal, Bocalini

and Silveira (2015) did measure culmen length and bill width, and mean

differences are about 0.4 and 0.1 mm respectively; even so, culmen width was

the main influence on Factor 2, yet crassirostris does not occupy

discrete morphospace.

“B1) YES,

reluctantly. Large-billed has some

history and syncs with the scientific name, but the Bocalini-Silveira analysis

indicates that this is a trend, not a real character. Does this bird stand out in the field as

having a larger bill than other Forpus in the group? Could applying this name be misleading?”

“B2) NO! For the same reasons as outlined by Dan

above. Crassirostris is not some

peripheral isolate but rather occurs in 4 countries in western Amazonia. For those of us who have worked there, this

is the taxon we called Blue-winged Parrotlet.

“C) YES. Parapatry

with no sign of gene flow is sufficient evidence for species rank for any taxa,

and as quantified by the Bocalini-Silveira analysis, this taxon is fairly

distinctive by Forpus standards.

“D1) YES - Turquoise-winged

Parrotlet already in use and a good name.

“D2) YES. In contrast to the crassirostris

situation, spengeli is a peripheral taxon with a vastly smaller range.

Comments

from Schulenberg on B1 and B2: “As far as Forpus

crassirostris and Forpus xanthopterygius are concerned, I

vote NO on both 'Large-billed' (crassirostris) and 'Blue-winged'

(retaining this name for xanthopterygius). 'Large-billed' just isn't a

great name to begin with, given that the difference in bill size between

nominate crassirostris and the other taxa is not large and or consistent

a difference (as noted by Van: "crassirostris does not occupy

discrete morphospace"). I wonder if anyone would accept something like

'Riparian Parrotlet' (similar to the case of Riparian Antbird Cercomacroides

fuscicauda), in a nod to the fact that it occupies open, river edge

habitats (and now, of course, a lot of second growth etc.). this habitat

preference isn't unique in the genus, but ... we're going to be limited by

color-based names, and 'Amazonian Parrotlet' already is taken (Nannopsittaca

dachilleae). or can anyone come up with anything better? otherwise, crassirostris

occupies a large enough geographic range that retaining 'Blue-winged' doesn't

seem wise to me. I don't think 'Cerrado Parrotlet' would work well, since I

take it that the range of Forpus xanthopterygius extends to west

to Beni, and for that matter well outside of the cerrado in eastern Brazil.

would 'Blue-rumped Parrotlet' work? I think that's been used before for Mexican

Parrotlet Forpus cyanopygius, but perhaps sufficiently long ago

that it wouldn't be a problem. or any other ideas?

“On the other hand, I'm perfectly fine with 'Turquoise-winged' for

spengeli, and with retaining 'Green-rumped' for passerinus.”

Comments

from Jaramillo on B1 and B2: I read Tom's comments, and like

that Riparian name. I will change my votes on the two.

F. crassirostris - NO to

Large-billed. Yes to Riparian if that is put forward.

F. xanthopterygius – NO, as it seems like we are going down the need to

get a new name put forward, I will help it get there more quickly then.

Comments from Donsker on on B1 and B2: “I recommend using the English names "Large-billed"

Parrotlet for F. crassirostris and “Cobalt-rumped Parrotlet” for F.

xanthopterygius.

“Although the

name Large-billed Parrotlet may not be at all helpful for diagnosis, the name

is at least a reasonable translation of the Latin species epithet, which may be

as useful a reason as any other to use it. (Thick-billed Parrotlet would be a

better translation, but I feat that’s too close to Thick-billed Parrot and is probably

best avoided). Besides the English name Large-billed Parrotlet has an

established history of usage at least traceable back to Brabourne & Chubb and

to Cory.

“I’d favor

changing the English name of F. xanthopterygius to avoid the potential

for confusion that Dan and Van have both expressed. “Blue-winged” Parrotlet is

the well-established English name for both the western Amazonian crassirostris

and the eastern Brazilian/Bolivian xanthopterygius. This becomes even more confusing given the unsettled

history of the scientific name applied to Blue-winged Parrotlet (sensu lato),

which has bounced around between F. crassirostris and F. xanthopterygius

over the mid to late 20th century.

But there is no other suitable historical English name for this form that

I am aware of. It’s a dilemma. I like Tom’s suggestion of Blue-rumped Parrotlet,

but I don’t think it would be wise to use it given the association of that name

with Mexican Parrotlet. But perhaps a

similarly constructed name? So, I’d propose Cobalt-rumped Parrotlet. "Cobalt" is a reasonable modifier for the

shade of the dark blue rump of this species. This has been variously described as

"rich blue" (Ridgely et al. 2016); ”violet-blue" (Forshaw &

Knight 2010); "cobalt-blue" (Juniper & Parr 1998); and

"azul-colbalto" (F. x. flavissimus) or

"azul-violeta" (nominate xanthoptergius)

(Grantsau 2010).”

Additional comments

from Remsen:

“I’m switching from Y to N on crassirostris just to force a

reconsideration of these names.”

Comments

from Bonaccorso:

“A. YES. The branch that conducts to F. x. crassirostris

is among the deepest in Forpus and is supported by both mitochondrial

and nuclear data.

“B. NO. Forpus passerinus spengeli is well within F.

passerinus to be considered another species. Until data on other characters

suggest that they are reproductively isolated from other F. passerinus,

they should remain as part of F. passerinus.”

Comments

from Stiles:

“This proposal (Forpus parrotlets) suffered from a confusion between the

proposal (A: split crassirostris from xanthopterygius, and

C: split spengeli from passerinus), and the way the voting

chart was given (A: split crassirostris from passerinus, and

C: split spengeli from xanthopterygius). Fortunately, the E-name proposals of the voting

chart under A and C got it right, and I am assuming that people followed

the proposal regarding the splits, although several simply said YES or

NO without specifying. Here are the splits: A passed 9:1. C passed 7:3. Because

some people did not vote on E-names, nothing reached quorum but both

Green-rumped for passerinus and Turquoise-winged for spengeli were

5:0 for YES. Large-billed was 3YES: 2NO for crassirostris, with two YES for

Riparian; for xanthopterygius, YES votes were 2 for Blue-winged, 1 for

Cerrado(?), 1 for Cobalt-winged (a late-comer, but I’m willing to switch to it

as well (so give it 2). This stalemate prompted taking up the issue again in

Proposal 900 (see below).”

Comments

from David Donsker:

B and D: “NO. to all I’d support "Riparian"

Parrotlet” for F. crassirostris and “Cobalt-rumped Parrotlet” for F. xanthopterygius.”