Proposal (879) to South American Classification Committee

Treat

Saltator coerulescens as two or three species

Effect

on SACC list:

Saltator coerulescens would be split into three species.

Background:

Paynter

(1970) treated Saltator coerulescens (with 13 different subspecies) as a

single species ranging from Mexico to Uruguay. In his Venezuela guide, Hilty

(2003) included a taxonomic note indicating that the Middle American grandis

subspecies group may be a separate species from the nominate South American

Saltator coerulescens group (a return to the classification of W. Deppe

1830). Hilty (2003) also mentioned that vocal differences within South America

may indicate additional species. Similar suggestions were also made elsewhere

(Ridgely & Tudor 2009, del Hoyo et al. 2011). In the absence of any further

study, all modern taxonomies however continued to treat Grayish Saltator as a

single species (until recently).

New

information:

Genetic

data:

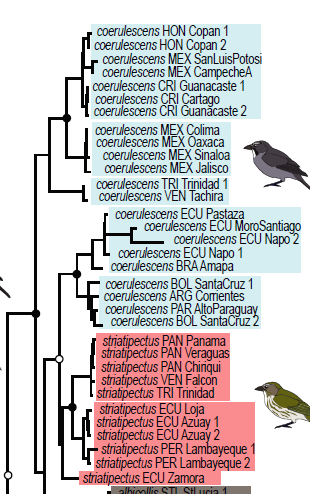

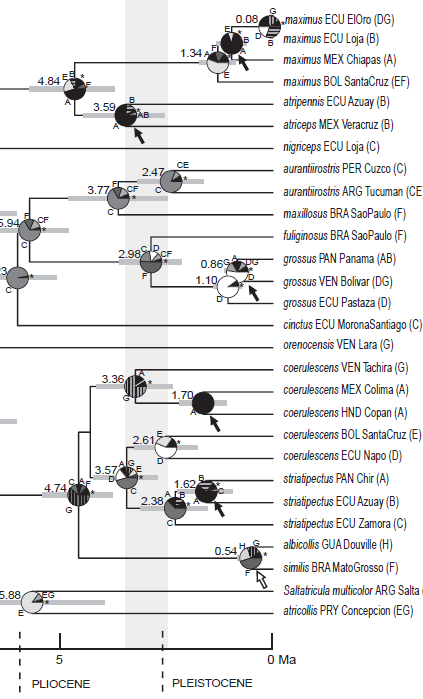

Chaves et al. (2013) presented a phylogeny of the genus Saltator. All

presently recognized species were found as monophyletic groups, with the

exception of S. coerulescens.

The

Amazonian group (coerulescens group) was found sister to Streaked

Saltator S. striatipectus (making the present broadly defined S. coerulescens

paraphyletic), whereas the Middle American grandis group was found

sister to the Caribbean group of northern South-America (the olivascens

group). Divergence times were estimated to be >3 million years in both

cases.

Chaves

et al. (2013) pointed out that taxonomically grouping the streaked vs

non-streaked taxa is in fact contradictory to his genetic findings, and

recommended additional research to better understand this apparent anomaly

(while putting forward as possible hypothesis that a parallel evolution leading

twice to a streaked plumage may be explained by a paedomorphic condition).

Vocal

data:

Boesman (2016) made a brief vocal analysis (without having learnt about the

findings of Chaves et al.) and found three clear vocal groups:

· The northern (or Middle

America) group (including vigorsii, plumbiceps, grandis,

yucatanensis, hesperis and brevicaudus)

· The Caribbean group

(including plumbeus, brewsteri and olivascens)

· The Southern (or

Amazonian) group (including azarae, mutus,

superciliaris and coerulescens)

The

Caribbean group differs from both other groups by the lack of long, slurred

notes, lack of a second song type, slower pace of stuttered song, etc. (The

fact that this group lacks a whistled song is possibly an evolutionary

adaptation to differ from the largely sympatric Streaked Saltator S.

striatipectus). The Amazonian group differs from the Northern group based

on a stuttered song with repeated notes (# of repeats) and a whistled song with

fewer notes and upslurred ending.

These

findings are very much congruent with Chaves’ findings of three groups

(including also the fact that the Amazonian group seems vocally closer to S.

striaticeps).

Morphological

data: del

Hoyo & Collar (2016) analyzed morphological differences, and concluded

these were small. The northern group typically has a longer white eyebrow and

more rufous-brown belly, and the Caribbean group has a more whitish central

belly.

Discussion:

Although

in the past two allopatric species have been suggested, it would seem that in

fact rather three clear groups are involved (a split of Middle American vs.

South American taxa would not amend paraphyly nor accommodate vocal

differences, and thus despite earlier suggestions is not recommendable).

The

Middle American group is allopatric, but the case of the two South American

groups is more intriguing. These seem to meet both along the lower east slopes

of the east Andes, and north of the Amazon delta. In both regions they are

likely parapatric, but this requires further study (a situation identical to

e.g. C. cyanoides vs. C. rothschildii along the Andes,

where exact boundaries and possible interaction also still need to be

uncovered). In both contact zones, there

seems to be a clear-cut (and identical) change in voice, which eliminates the

possibility of some type of ‘ring species’ based on voice.

Since

the Boesman (2016) analysis, a few additional sound recordings have been

deposited on-line from the contact

zones, further confirming the sharp vocal transition along the Andes:

ML59164651 is just north of the rio Meta (at a distance of c 30km from XC327455

!), is of the ‘Caribbean group’ and further indicates parapatry. (No new

recordings from the eastern contact zone).

Learnt

voice in oscine passerines calls for some caution, but it should be noted that

in the genus Saltator, several other clear-cut cases are based on vocal

differences between related species pairs (and confirmed by genetics) for which

prior classifications based on morphology were not always in accordance (e.g. S.

nigriceps vs S. aurantiirostris; Boesman 2016b).

Genetically,

calculated time of divergence of the three groups was comparable to the widely

accepted species pairs S. grossus vs S. fuliginosus, S. atripennis

vs S atriceps or S. aurantiirostris vs. S. maxillosus (all pairwise

sister species). A weakness is that the Caribbean group was only analyzed by

two (admittedly widely separated) samples and that Bayesian PP<0.75.

Ideally,

to make this case more robust, besides more extensive genetic sampling,

play-back experiments could be added (although e.g. playing the whistled song

of Amazonian group to Caribbean group is in fact about the same as playing song

of the sympatric Streaked Saltator, with predictable result).

Furthermore,

study of the situation in the contact zones of the 2 South-American groups

would allow for a better assessment of interactions between both groups. The

fact that such potential contact exists (twice) without any indication of

clinal variation at the other hand is a strong argument absent when dealing

with allopatric populations.

It

would thus seem that the following viable taxonomic options exist:

· Retain the present

treatment while awaiting more research, accepting paraphyly and highly

divergent vocal groups within a single species

· Split the southern

group, thus creating two monophyletic groups, but still having a

(northern/Caribbean) species with two very distinct vocal groups

· Split into three

species, all monophyletic and with distinct voice

Southern

Grayish Saltator is the English common name given by Hilty (2003) presumably

for all taxa in South America (but confusingly he described the range from

Mexico to Uruguay), and by deduction the Middle American group may be called Northern Grayish

Saltator. Del Hoyo & Collar (2016) recognized three species, and named them

Northern Grey Saltator, Caribbean Grey Saltator, and Amazonian Grey Saltator.

By keeping Grey (or Gray) in the name, the link with the former name Grayish is

retained. ‘Caribbean’ is not very precise for a bird with a range well inland,

but Caribbean Hornero, for example, has been used as well elsewhere, and the

name ‘Northern’ is not an option here, with ‘Guianan’ not correct either etc.

‘Amazonian’ is also somewhat ‘stretched’ given the range of that group reaches

the Chaco of Argentina. ‘Southern’ is an alternative.

Proposal:

A.

Split

S. coerulescens into two monophyletic species: S. grandis (including also vigorsii, plumbiceps,

yucatanensis, hesperis, brevicaudus,

plumbeus, brewsteri and olivascens) and Amazonian S. coerulescens

(including also azarae, mutus and

superciliaris)

B.

If

A is accepted, split S. grandis into two species: Middle American S.

grandis (including also vigorsii, plumbiceps, yucatanensis, hesperis,

brevicaudus) and Caribbean S. olivascens

(including also plumbeus and brewsteri)

C.

Give

English common names respectively as Northern Gray Saltator, Caribbean Gray

Saltator (if B is accepted) and Southern Gray Saltator (if NO, please provide

alternative)

Literature:

Boesman, P. (2016).

Notes on the vocalizations of Greyish Saltator (Saltator coerulescens).

HBW Alive Ornithological Note 395. In: Handbook of the Birds of the World

Alive. Lynx Edicions, Barcelona. https://doi.org/10.2173/bow-on.100395 https://static.birdsoftheworld.org/on395_greyish_saltator.pdf

Boesman, P. (2016b).

Notes on the vocalizations of Black-cowled Saltator (Saltator nigriceps).

HBW Alive Ornithological Note 440. In: Handbook of the Birds of the World

Alive. Lynx Edicions, Barcelona. https://doi.org/10.2173/bow-on.100440 https://static.birdsoftheworld.org/on440_black-cowled_saltator.pdf

Chaves, J.A., Hidalgo,

J.R. and Klicka, J. (2013). Biogeography and evolutionary history of the

Neotropical genus Saltator (Aves: Thraupini). Journal of Biogeography.

40(11): 2180–2190.

Del Hoyo, J., Elliott, A.

and Christie, D. (2011). Handbook of the Birds of the World Vol. 16. Lynx Edicions.

Barcelona.

Del Hoyo, J. &

Collar, N. (2016). Illustrated checklist of the Birds of the World. Lynx Edicions.

Barcelona.

Hilty, S.L. (2003). Birds

of Venezuela. Christopher Helm, London

Ridgely, R.S. and

Tudor, G. (2009). Field Guide to the Songbirds of South America: The

Passerines. University of Texas Press, Austin, Texas.

Paynter, R. A.,

JR. (1970). Subfamily Cardinalinae. Pp.

216-245 in "Check-list of birds of the World, Vol. 13" (R. A. Paynter

Jr., ed.). Museum of Comparative Zoology, Cambridge, Massachusetts

Peter Boesman, August

2020

Comments

from Areta:

“A. YES. The genetic

differentiation, with coerulescens as

sister to the vocally and morphologically different striatipectus support the split.

“B. YES. The depth of

the split between olivascens and grandis is similar to that between coerulescens and striatipectus, and although they are less divergent in plumage,

their vocalizations and amount of genetic differentiation argue in favor of

this split as well.

“C. NO. Unfortunately,

I am not allowed to vote. These compound names are awful and should be avoided,

while the imply a relationship that does not exist. I would go with something

along the lines of:

Cinnamon-bellied Saltator --- S. grandis

Drab-bellied Saltator --- S. olivascens

Grayish Saltator --- S. coerulescens

“I

don´t see any need to change the name of the nominate taxon, which is also the

most widespread.”

Comments

from Stiles:

“A: YES to splitting grandis from coerulescens: genetics, distributions

and vocalizations provide strong support. B: YES to the further split of olivascens from coerulescens: genetics, vocalizations and considerable evidence for

parapatry, albeit with only a small difference in plumage seem sufficient for

this split, which also resolves the paraphyly of coerulescens. C. E-names: I like Nacho’s suggestion for these.”

Comments

from Robbins:

“Given the genetic and vocal data, YES, to both A & B for recognizing grandis

and olivascens as species.”

Comments

on English names from Josh Beck: “I strongly agree that proposed names are misleading with

respect to relationships that don't exist. I like Nacho's novel name of

Cinnamon-bellied for grandis, but I would like to suggest that Caribbean

Saltator might be a better name than Drab-bellied for olivascens. The

name Caribbean Gray(ish) Saltator is already in use

in a few places (BirdLife, EcoRegistros, and as the

group name for olivascens in Clements/EBird/BotW).

Drab-bellied is not really all that informative/unique in a genus full of

fairly drab bellied birds. But mostly, it seems a more useful name in that it

ties the species to its distribution. To me it reminds me of the names

"Rio Suno, Rio de Janeiro, and Yungas Antwrens" vs "Gray,

Leaden, and Slaty." There's nothing really wrong with the colors for

names, but the three geographically inspired names tell you a lot more right

off the bat. One could follow that logic to suggest that Guianan Saltator might

be an even better name based on the range of olivascens, but with

precedent for Caribbean Gray Saltator, it seems Caribbean Saltator is a less

disruptive choice than Guianan.”

Comments from Zimmer: “A. YES to splitting Middle American + Northern

SA subspecies in this complex from “Amazonian” or southern coerulescens (including azarae,

mutus and superciliaris,

based upon genetics, voice, and morphology as outlined in the Proposal. (B) YES to further splitting Caribbean S. olivascens (including plumbeus and brewsteri) from the Middle American S. grandis group (including vigorsii, plumbiceps, yucatanensis, hesperis,

and brevicaudus).

(C) NO to the proposed compound English names of “Northern Grayish Saltator”,

“Caribbean Grayish Saltator” and “Southern Grayish Saltator”. The compound names, although somewhat bland,

are descriptive enough of the distributions of the three groups, but my

objection lies in the genetics, which tell us that the southern coerulescens-group is sister to Streaked

Saltator, making the broader coerulescens-group

currently defining Grayish Saltator paraphyletic. Thus, it would seem inappropriate to use

“Grayish Saltator” as a group name, when the implied group relationship doesn’t

exist. Normally, I would want to steer

clear of retaining the parental English name for one of the “daughters” in a

3-way split, but given that, in this case, the nominate taxon is the most

widespread, and, technically, the other two species resulting from the split

are not true daughters, perhaps retention of “Grayish Saltator” for post-split coerulescens is the best course, as

Nacho suggests. I also rather like

Nacho’s suggestion of “Cinnamon-bellied Saltator” for the grandis-group. For the olivascens-group, I would suggest either

Olive-gray Saltator or Gray-olive Saltator, which is perhaps more descriptive

than “Drab-bellied”, would square nicely with the species epithet, and would

also provide a link to its former status as part of “Grayish” Saltator.”

Comments from Bonaccorso: “A. NO. From the Chaves et

al. (2013) tree, it is not completely clear that the Caribbean clade is most

closely related to the Middle American clade; they probably are, but there is

no support for the node that unites those two clades. Also, their vocalizations

are different enough to suggest they are both good biological species.

“B. YES. Given the phylogenetic uncertainty about the

relationship between the Caribbean and the Middle American clade, it makes more

sense to recognize three species of Saltator (S. grandis, S.

olivascens, and S. coerulescens). All three species are easily

differentiated by song, make sense geographically. The relationships between

the Caribbean clade and other clades in Saltator will not change that.”

Comments

from Jaramillo:

“A. YES. B. YES. Vocal and genetic data

suggests this is the way to go. I am impressed that the vocal change is clear

at the contact zones, although I realize data is minimal still at the contact

zones. C – NO.

“I

would not keep Grayish Saltator as that will really cause confusion over time

in this case. How about just shortening to Gray Saltator? Remember names do not

need to be perfect. Cerulean is another option, but perhaps that is too much of

a stretch. I like Cinnamon-bellied. However, I think it is a big stretch to use

Caribbean for olivascens as someone who is novel to this situation will

not be looking for it in Colombia and Venezuela, but in Cuba and Puerto Rico if

you use Caribbean. Again, with leniency to names that are not perfect but at

the same not entirely incorrect why not Olivaceous Saltator? Given the region,

and Simon Bolivar’s wish for a “Gran Colombia” one could propose Gran Colombian

Saltator, just throwing spaghetti at the wall here to see what sticks. Having

some fun. Suggestions in the quest of good, memorable and simple names:

Cinnamon-bellied Saltator --- S. grandis

Olivaceous Saltator --- S. olivascens

Gray Saltator --- S. coerulescens

Comments

from Lane:

“Comments by Lane: A) YES. B) YES. C) NO to the

proposed names by the proposal. I am inclined to use the names suggested by

Alvaro, but perhaps modify his coerulescens name to "Blue-gray

Saltator" to better distinguish it from "Grayish" and to better

square with the blue implication of the scientific name.”

Comments from Pacheco: “YES, for A and B. Considering

the genetic and vocal data, I vote to recognize both grandis and olivascens

as full species.”

Comments from Claramunt: “NO. Given the morphological

similarity, I think we should be more cautious. The relevant nodes in the ND2

tree are not strongly supported, so I think that the evidence for the paraphyly

of coerulescens is not strong. Note also that there are no samples from

nowhere near a putative contact zone in Colombia. The closest samples are in

Ecuador and Venezuela. I would like to see some nuclear data and/or samples

from Colombia, and/or a more rigorous analysis of the match between mtDNA and

songs.”

Comments from Remsen: “A and B. NO.

Declaring paraphyly based on an ND2 gene tree is just not acceptable,

especially when the sampling is haphazard and not designed to detect gene flow

near contact zones. Even so, as pointed

out by Elisa and Santiago, support for the important nodes is not strong. This is a nice preliminary study that should

set the stage for a more rigorous project that focuses on contact zones. As for the vocal data, they are indeed

suggestive in that they map onto the genetic data fairly well. But again, I’d

like to see a full-blown analysis with samples from near contact zones as well

as playback trials. Peter has set the

stage for a more formal analysis. I am

tempted to vote YES just because I think the proposed species limits are

probably a better match for the limited published data than treating them all

as conspecific. But this group is

complex and deserves a well-designed study with better genetic data, samples

from the contact zones, and playback experiments, and comparisons including striatipectus

and albicollis.

C. NO. The compound names

(with or without hyphens) imply a monophyletic group, when in fact their

potential non-monophyly is the basis for part of the proposal. As for some of the suggestions, “Grayish” is

DOA. The nominate form may have a larger

distribution, but even S. grandis sensu stricto has a large distribution

that includes basically all Middle American countries (and likely therefore has

more citations in literature). We need a

separate proposal on English names if the taxonomic proposal passes.”

Comments from Oscar Johnson solicited by Remsen: “You're definitely right that this is just a gene tree, so it

should clearly be interpreted with caution. Additional data from next-gen

nuclear data will likely change some of the results, but looking at some recent

studies that have included both mtDNA and next-gen nuclear data for the same

samples, the mtDNA often gets quite close to the latter. So, I do think that

mtDNA provide a reasonable estimate of relationships (with caveats) and are a

good first pass at a phylogeny that can be useful in taxonomic decisions. MtDNA

will give conflicting signals (vs next-gen) in cases of recent introgression

(haploid, matrilineal, etc) or with incomplete lineage sorting (gene

tree/species tree), but it does seem to do a good job of clustering populations

and estimating relative divergence times. Having many fewer base pairs to work

with does usually lead to lower support across the phylogeny, too. For examples

of the similarities between mtDNA and next-gen phylogenies, check out the

recent Aphelocoma papers from the McCormack lab, Ethan Linck's WEFL paper (buried in supplemental), or my Epinecrophylla

paper.

“For

this Saltator paper, I would trust, for example, that there are two deeply

diverged clades in coerulescens. The paraphyly of coerulescens

could be due to gene tree/species tree conflict or insufficient signal in the

mtDNA, but there is clearly a deep genetic separation across the Andes that is

indicative of two species. I wouldn't be surprised if a study of nuclear data

found coerulescens to be monophyletic with a deep split across the

Andes. In that larger clade, I would say you've got four divergent genetic

groups (each reasonably called species), but the relationships between them are

poorly resolved (note low statistical support for many branches): two coerulescens

with a split across the Andes, striatipectus, and albicollis/similis.

Albicollis and similis are clearly very closely related (which is

quite amazing, in my opinion), despite the geographic separation and clear

morphological differences.

“The

situation with maximus is weird. there are clearly two deeply diverged

clades suggestive of species, but the western Ecuador populations cluster with

the Amazonian birds. I would be hesitant to split maximus, despite the

deep divergence, as that result suggests that something interesting is going on

in Colombia (unsampled), either with genetically intermediate populations that

would "fill in" that deep divergence or with secondary contact

somewhere between the closest samples in the study (western Ecuador and western

Panama). By "filling in" the

relationships for maximus, I mean that there could be additional deeply

diverged clades in Colombia. It wouldn't change the fact that there is a deep

divergence within the species. I think you would just need to get more

information on where exactly those populations come back into contact.”

“For some of the other groups:

“S. grossus and S. fuliginosus are clearly very closely related, or

hybridized relatively recently. Maybe same species? More data probably needed.

“There are really not enough samples or statistical support

to make any inferences about maxillosus and aurantiirostris,

especially given reports of hybridization between these taxa. That's a

situation that would need lots of nuclear data.”

“Regarding plumage/vocalizations, yes,

hopefully those line up with the major genetic breaks, which would provide

additional evidence for species status.”

Comments

from Stiles:

“Splitting up Saltator coerulescens. Three groups had both genetic and

vocal support (again, thanks to Peter Boesman): call them M (Middle American grandis

and sspp.), C (the ± Caribbean olivaceus and sspp.) and A (Amazonian

coerulescens). Maintaining all in

a single species is not an option because this leaves the species (Grayish

Saltator) parapatric. Additional data: M is isolated geographically; probable

parapatry exists between C and A). The proposal to split M from C+A passed 7-3;

the proposal to split the two South American clades C and A passed 8-2. The

problems derive from the derivation of E-names for the three groups. I’d

suggest presenting the options here as two slates: geography, with the names

Middle American (or Northern), Caribbean and Amazonian) vs. color differences:

Cinnamon-bellied for grandis, Drab-bellied or Olive-gray (or

Olivaceous?) for olivaceus, and Grayish (retaining the name for the

original species), Blue-gray or Leaden (another option, perhaps more accurate

and eliminating “gray” from the name) for coerulescens. First, vote for

the slates: geography vs. color – if one of these gets a clear majority, then

present the options for each of the species, perhaps numbering the options in

order of preference for each (where two or more options have been suggested).”

Comments

solicited from Don Roberson: “After reading the material, I quite like a combo of Alvaro's

names plus Dan Lane's modification of the nominate, and off the cuff I think

the following list is fine: short names, generally aimed at i.d. points, and a

new name for the nominate that includes the concept of "gray/grey".

Cinnamon-bellied Saltator --- S. grandis

Olivaceous Saltator --- S. olivascens

Blue-gray Saltator --- S. coerulescens”