Proposal (885) to South

American Classification Committee

Revise the generic classification of the

Xolmiini

Two recent studies proposed alternative generic

classifications for the Xolmiini: Ohlson et al 2020 and Chesser et al 2020.

Their proposals were largely coincident but differed in how broad the genus Nengetus should be. Our subproposals

here broadly coincide with these two papers but differ in the treatment of Nengetus.

We recommend a YES vote to all of the

subproposals.

A) Include

pyrope in Pyrope (YES) or do something else (NO)

The highly distinctive Patagonian forest pyrope was found as stemming from a deep

node in both studies, supporting the recognition of the old genus Pyrope, of which it is the type species.

B) Include

rufipennis in Cnemarchus (YES) or leave in Polioxolmis

(NO)

Both species in this clade are rather elongated,

upright-perching, high-altitude specialists that deliver shrill whistles and

share the same tail pattern. We favor merging them in a single genus, which

would emphasize the common theme between them in plumage, habitat associations

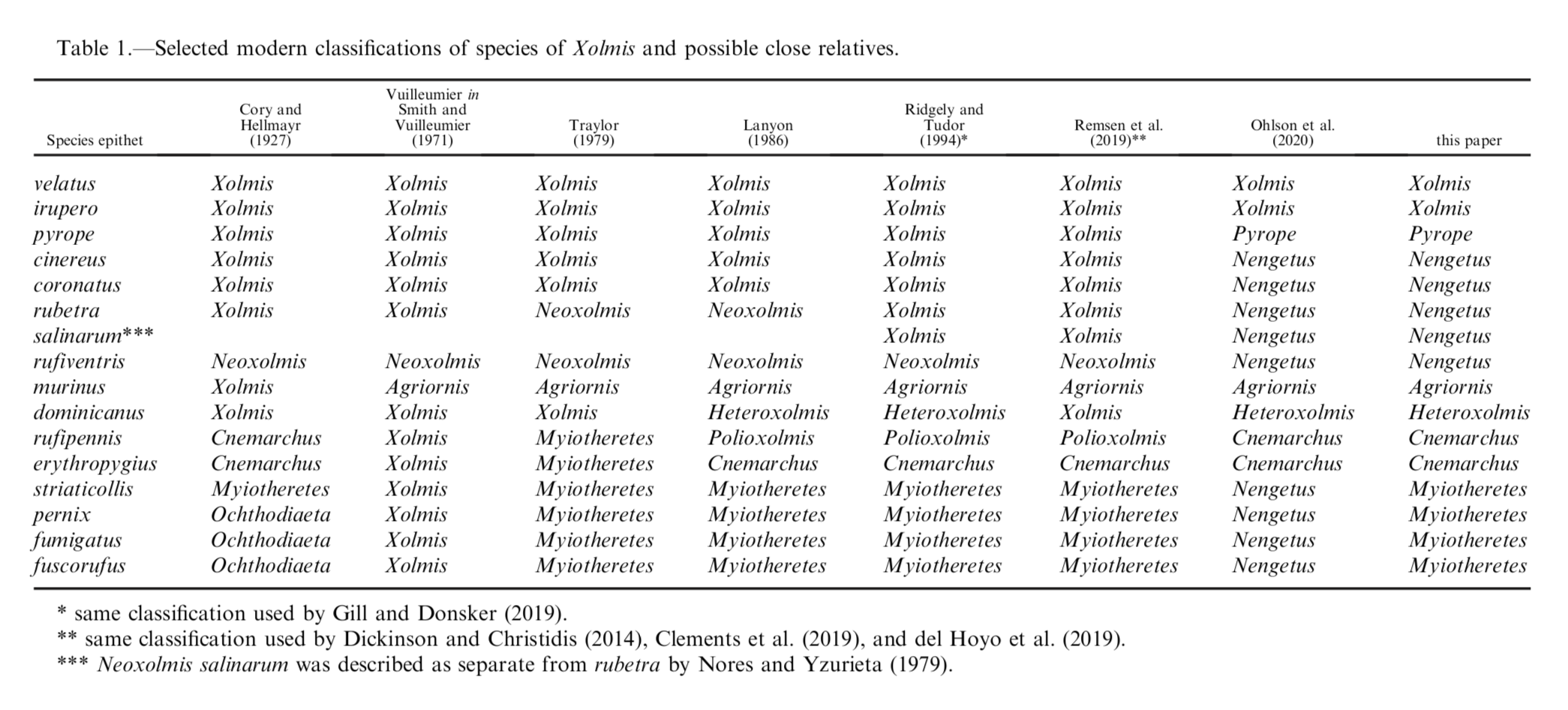

and vocalizations. This treatment has been followed in the past (see table from

Chesser et al 2020).

C)

Restrict Xolmis to irupero and velata (YES) or do something else (NO)

This is a rather straightforward decision, as

both species formed a coherent clade in both studies and the type species of Xolmis is irupero.

D) Use Myiotheretes for 4 species (YES) or

merge Myiotheretes under Nengetus (NO).

Myiotheretes is a very homogeneous genus comprising four

Andean species of reddish/brownish birds that deliver simple monotone flat

whistles and inhabit the tree-line zone. The continued recognition of Myiotheretes implies stability and is

consistent with the recovery of this clade in both studies.

Ohlson

et al. (2020) proposed to merge Myiotheretes

in an expanded (and heterogeneous) Nengetus,

stemming from the placement of cinereus

in their phylogeny. However, this merger is not consistent with the position of

cinereus in the work by Chesser et al.

(2020) and would create a large and very heterogeneous grouping of birds. The

best way out of this is to recognize Myiotheretes,

which would imply no change in our classification.

E) Use Nengetus only for cinereus and Neoxolmis

for coronatus, rubetra, salinarum, and rufiventris (YES) or use Nengetus for all the taxa (NO)

As in the case of Myiotheretes, the rather obscure genus Nengetus is again at the center of conflict. Both studies advocate

a rather broad use for Nengetus, but

we believe this is not good for two reasons 1) it creates too heterogeneous

groupings and 2) it disrupts stability.

Reasons

for restricting usage of Nengetus for

cinereus

The type of Nengetus

is cinereus, a widespread species

with distinctive plumage that lives in open savanna areas. This distinctiveness

is also evident in the deep genetic divergence with other species in the clade.

Besides these aspects, cinereus does

not walk on the ground regularly or at all (unlike the other species usually

placed in Neoxolmis) and inhabits

more humid and generally lowland areas (reaching higher altitude in southern

Brazil, a pattern exhibited by many "Pampas" birds), whereas the

other species are all exclusive to arid areas mostly in the extreme southern

portion of the continent. Finally, the position of cinereus might be open to discussion (see contrasting results in

Ohlson et al 2020 and Chesser et al 2020 discussed also in Subproposal D); thus,

we do not recommend expanding Nengetus

any further beyond its type species, cinereus.

Reasons

for placing four species in Neoxolmis

The four species that would be included in Neoxolmis (rufiventris, rubetra, salinarum and coronatus) are all species of dry, extreme areas that regularly

walk on the ground (less often in coronatus).

Their nests are made of sticks on the ground or in shrubs are remarkably

similar, as are their eggs. They form a monophyletic group in both the Ohlson

et al. (2020) and Chesser et al. (2020) studies. Traylor (1979) and Lanyon

(1986) already recognized a close relationship of rufiventris+rubetra/salinarum

when placing them together in the genus Neoxolmis

(see table from Chesser et al 2020 above). In sum, they form a far more

coherent grouping when cinereus is

excluded. Moreover, using Neoxolmis

has the advantage of using a name that has already been in wide use and which

recognizes that they are in some way akin to "Xolmis". Having direct field experience with all the Xolmiini

species, and with 3/4 species being endemic breeders to Argentina, we are

convinced that using Neoxolmis is the

best possible solution, which is consistent with genetic evidence, supported by

field data and which best serves stability.

We think that, based on the deep genetic divergence

and plumage differences, the Argentine endemic breeder coronatus may merit a new genus. However, no such genus name is

available and at present it seems easier and less disrupting to place it in Neoxolmis together with the other

species in this clade of austral birds.

F)

Recognize Syrtidicola for fluviatilis (YES) or keep in Muscisaxicola (NO)

A deep divergence time, possible sister

relationship to Satrapa and

morphological and ecological differences (e.g., very short tail, lowland

inhabitant of riverine sand bars) lead Chesser et al. (2020) to describe a new

genus for fluviatilis.

G)

Sequence. The sequence we need to adopt would be this one

(YES) or another one (NO):

Muscisaxicola

fluviatilis

Little

Ground-Tyrant

--- Syrtidicola

Muscisaxicola

maculirostris

Spot-billed

Ground-Tyrant

Muscisaxicola

griseus

Taczanowski's

Ground-Tyrant

Muscisaxicola

juninensis Puna

Ground-Tyrant

Muscisaxicola

cinereus

Cinereous

Ground-Tyrant

Muscisaxicola

albifrons White-fronted

Ground-Tyrant

Muscisaxicola

flavinucha

Ochre-naped

Ground-Tyrant

Muscisaxicola

rufivertex

Rufous-naped

Ground-Tyrant

Muscisaxicola

maclovianus

Dark-faced

Ground-Tyrant

Muscisaxicola

albilora

White-browed

Ground-Tyrant

Muscisaxicola

alpinus

Plain-capped

Ground-Tyrant

Muscisaxicola

capistratus

Cinnamon-bellied

Ground-Tyrant

Muscisaxicola

frontalis

Black-fronted

Ground-Tyrant

Cnemarchus

erythropygius

Red-rumped

Bush-Tyrant

Polioxolmis

rufipennis

Rufous-webbed

Bush-Tyrant

--- Cnemarchus

Xolmis

pyrope

Fire-eyed

Diucon --- Pyrope

Xolmis

velatus

White-rumped

Monjita

Xolmis

irupero

White Monjita

Xolmis

cinereus

Gray Monjita --- Nengetus

Xolmis

coronatus

Black-crowned

Monjita

--- Neoxolmis

Xolmis

salinarum

Salinas Monjita --- Neoxolmis

Xolmis

rubetra

Rusty-backed

Monjita

--- Neoxolmis

Neoxolmis

rufiventris

Chocolate-vented

Tyrant ---Neoxolmis

Agriornis

montanus

Black-billed

Shrike-Tyrant

Agriornis

albicauda

White-tailed

Shrike-Tyrant

Agriornis

lividus

Great

Shrike-Tyrant

Agriornis

micropterus

Gray-bellied Shrike-Tyrant

Agriornis

murinus

Lesser

Shrike-Tyrant

Myiotheretes

striaticollis

Streak-throated

Bush-Tyrant

Myiotheretes

pernix

Santa Marta

Bush-Tyrant

Myiotheretes

fumigatus

Smoky

Bush-Tyrant

Myiotheretes

fuscorufus

Rufous-bellied

Bush-Tyrant

H)

Recognize Heteroxolmis. The Black-and-white Monjita was found to not even belong in the

Xolmiini, so a return to the genus Heteroxolmis

is warranted. It was found to be more closely related to other "warm"

grassland specialists (Alectrurus

spp. and Gubernetes yetapa) in the

Fluvicolini. Ohlson et al 2020 stated:

"Recognize Heteroxolmis Lanyon, 1986 (type = Tyrannus dominicanus (Vieillot) for Xolmis dominicanus and remove it from Xolmini

to Fluvicolini. The distinctiveness of dominicanus

from other Xolmis species was

recognized by Lanyon (1986) based on morphological characters of the nasal

capsule and syrinx, but he regarded the two genera as close relatives. Among the character states that

motivated a separation from Xolmis is

a fully ossified nasal capsule, including alinasal

walls and turbinals, which is also found in Alectrurus

Vieillot, Gubernetes Such, Fluvicola Swainson and Arundinicola d’Orbigny (Lanyon 1986). As

the gender of Heteroxolmis is

feminine (see Lanyon 1986, fig. 24), the name of the species becomes Heteroxolmis dominicana.”

Xolmis dominicanus Black-and-white Monjita --- Heteroxolmis

A YES

vote would resolve Xolmis dominicanus

as Heteroxolmis dominicana and place

it in the sequence between Alectrurus

and Gubernetes.

Nacho Areta & Mark Pearman, September 2020

References

Chesser, R.T., M. G. Harvey,

R. T. Brumfield and E.P. Derryberry (2020) A revised classification of the

Xolmiini (Aves: Tyrannidae: Fluvicolinae), including a new genus for

Muscisaxicola fluviatilis. Proceedings of the Biological Society of Washington

133:35–48

Ohlson J.I., M. Irestedt,

H. Batalha Filho, P.G.P. Ericson and J.

Fjeldså (2020) A revised classification of the fluvicoline

tyrant flycatchers (Passeriformes, Tyrannidae, Fluvicolinae). Zootaxa 4747:

167–176

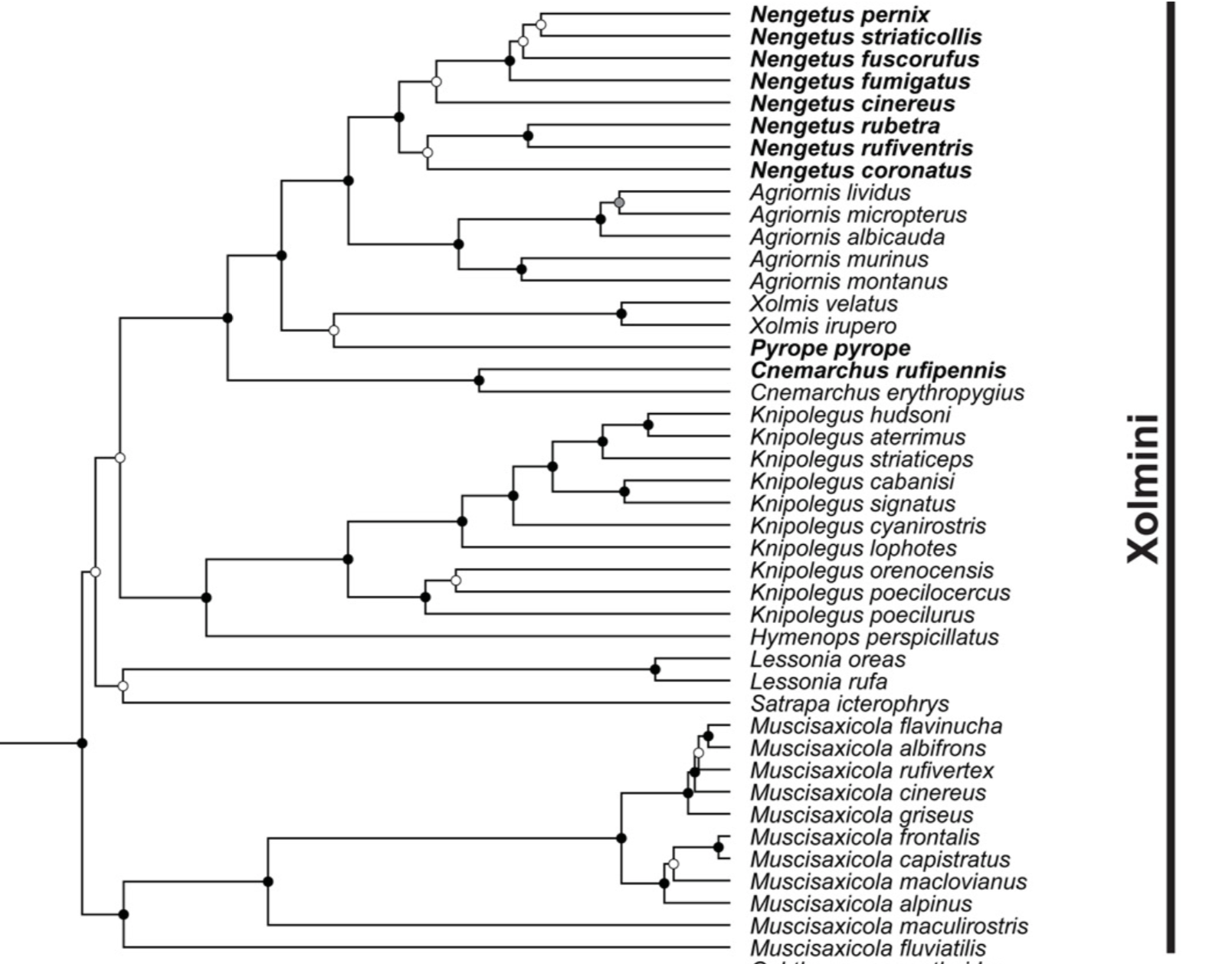

Tree from

Ohlson et al 2020

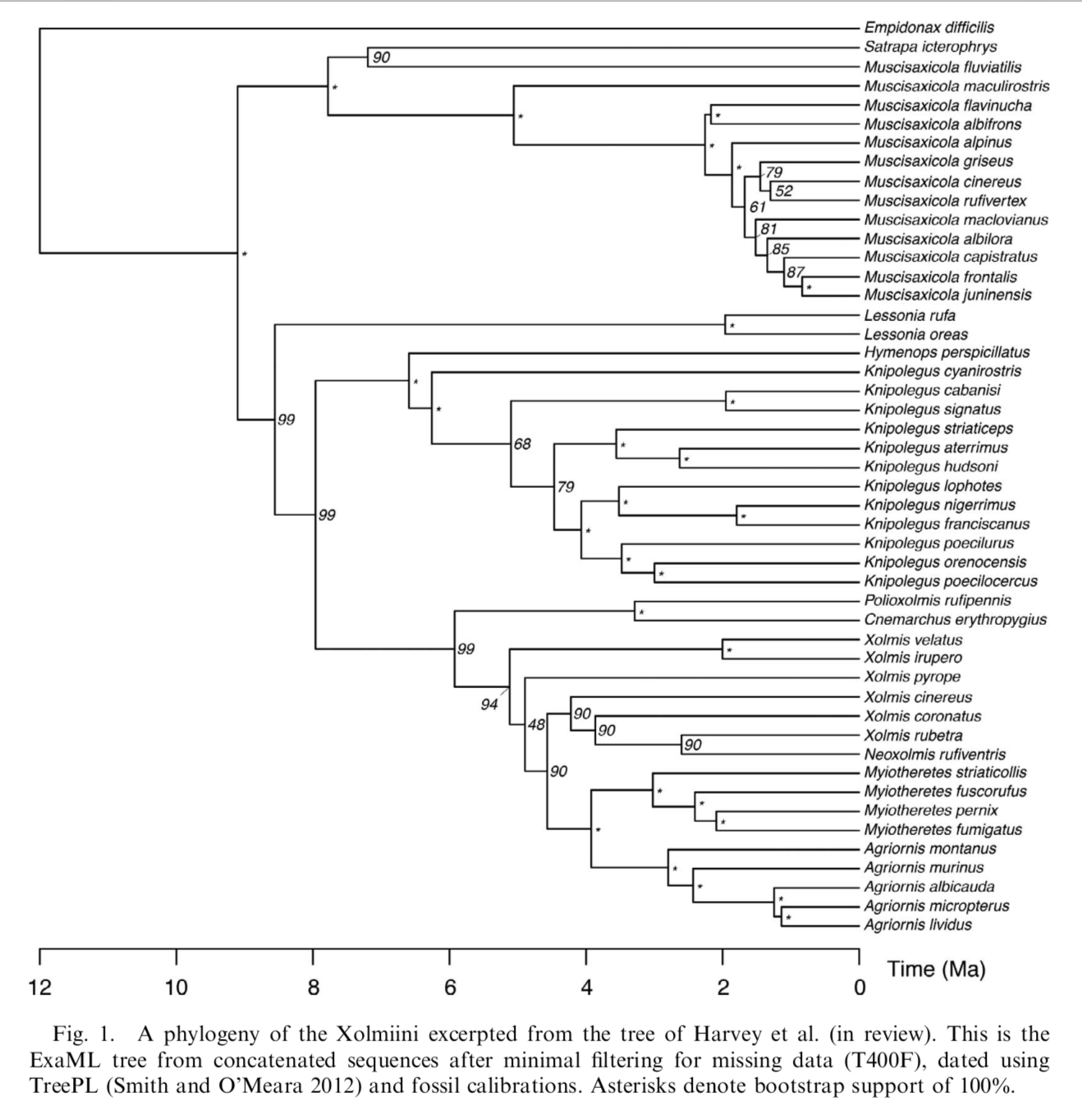

Tree from

Chesser et al 2020

Table from

Chesser et al 2020

Comments

from Robbins:

“YES to all proposals except E. With

regard to E, looking at the genetic data it does not make sense to break up

this clade by separating cinereus from the others. If one was going to apply a consistent

treatment (note the branch length of coronatus is similar to cinereus),

one either treats these as three different genera or all the same. The latter seems more reasonable to me.”

Comments

from Stiles:

“YES to all. When behavior, ecology and biogeography

are combined, I agree with Kevin that cinereus is best separated in a

monotypic Nengetus.”

Comments from Lane: “A) YES. B) NO. These two species

don't strike me as being all that similar in their behaviors, particularly the

Kestrel-like hovering that is so characteristic of Polioxolmis. I would

prefer to keep them as two monotypic genera. C) YES. D) YES. E) YES. F) YES

(emphatically!). G) YES. H) YES.”

Comments from Claramunt: “YES to all.

“After going back and forth on E, I ended up liking the proposed

solution: a monotypic Nengetus plus a diverse Neoxolmis.

Morphology, plumage and behavior are not of much use here as there is no

satisfactory way of subdividing the entire clade based on these. Excluding cinerea

doesn’t make the remaining Neoxolmis a nice homogeneous bunch. And even

separating coronata does not solve the issue, as rufiventris is fairly different

from rubetra and salinarum. What persuaded me at the end was the

argument of nomenclatural stability. This is because: 1) the resurrection of

the obscure Nengetus would affect only a single species (cinerea);

2) At least rufiventris, and rubetra and salinarum

according to some classifications, would retain their traditional generic

names; 3) The nomenclature would not change even if cinerea is found to

be closer to Myiotheretes (as in Ohlson et al.). So, at the end,

stability prevailed over my dislike for monotypic genera.”

Comments from Jaramillo:

“A. YES – The loss of Pyrope

never quite sat well with me; this new dataset correlates with the fact that

this is quite a different bird from typical Xolmis.

B. No – I agree with

Dan, that they should be left as monotypic genera.

C. YES – is it velata

or velatus though?

D. YES – retain Myiotheretes

for the 4 species, retaining a well-defined and morphologically cohesive genus.

E. YES – I hesitated,

thinking that coronatus perhaps deserved to be separate. However, it is

already in Xolmis with various of the other species that will now go to Neoxolmis

and I was OK with that. Definitely cinereus is the odd one out here, a

rather shrike like species, quite unlike the rest.

F. YES – and note that

I would be amenable to a separate genus for maculirostris as well. Not

only due to the different morphology of that bird, but a distinct voice, unlike

the very vocally simple Muscisaxicola (in the strict sense)

G. YES – adopt the new sequence.

H. YES – rather unexpected in some ways. It was

always different, but I would have expected it was a relative to true Xolmis

as we knew it. The membership in the grassland tyrants makes a certain amount

of logic as well.”

Comments from Pacheco: “YES to all proposals except E,

for consistency with the adoption of expanded Nengetus implemented by

CBRO.”

Comments from Remsen: “YES to all, except that using

the Chesser et al. tree, Xolmis must precede Pyrope following

standard conventions.”