Proposal (907) to South

American Classification Committee

Split Red-eyed Vireo (Vireo olivaceus) into two species

Note from Remsen: Below is a proposal that was passed by NACC and is posted here with

permission from its authors. It was

included in the 59th Supplement (Chesser If it passes, it would

result in SACC treating boreal migrant populations as one species: Red-eyed

Vireo (V. olivaceus) and Chivi Vireo (V. chivi).

Background: Current taxonomy recognizes the Red-eyed Vireo

(Vireo olivaceus) as one species with

two allopatric groups during the breeding season, which become sympatric during

the nonbreeding season (AOU 1998). Ridgway (1904) referred to the species as

monospecific, but a long history of debate has surrounded this species and the

complex of related species. The two allopatric groups are known as olivaceus and chivi. The olivaceus group

includes one or two migratory subspecies that breed in North America and spend

the winter in South America. The chivi group

includes nine subspecies from South America that consist of sedentary and

migratory populations (Cimprich et al. 2000). The

main reasons why both groups have been referred to as subspecies are their

subtle plumage differences and the eye color of adults, which is red in olivaceus and brown in chivi (Johnson and Zink 1985).

Johnson and Zink (1985), using starch gel

electrophoresis, showed that the two geographically disjunct groups of the

Red-eyed Vireo are conspecific. In that study they included 17 olivaceus samples from North America, 14

chivi samples from Paraguay (only the

diversus subspecies), 1 sample of V. flavoviridis, and 1 sample of Cyclarhis gujanesis as an outgroup.

Subsequently, Slager et al. (2014) reconstructed a phylogeny of the Vireonidae

family using the complete mitochondrial gene ND2, which suggests that the two

disjunct groups of V. olivaceus do

not represent sister clades. In their phylogeny, the North American lineage is

more closely related to populations of V.

flavoviridis from Yucatán, Mexico, whereas the South American lineage is

more closely related to V. altiloquus.

Slager et al. (2014) concluded that the reciprocal monophyly recovered by

Johnson and Zink (1985) might represent an artifact of incomplete taxon

sampling. However, they recommended analyses using more loci to fully resolve

the species relationships.

New Information:

Battey and Klicka (2017) published a

phylogenetic study of the Red-eyed Vireo species complex. The aim of this study

was to identify cryptic species and to assess rates of gene flow in a lineage

that includes migratory species that alternate between sympatry and allopatry

during an annual cycle. Battey and Klicka (2017) analyzed 40 individuals and 6

species of Vireo, which included four

members of the Red-eyed Vireo complex: V.

olivaceus, V. flavoviridis, V. altiloquus, and V. magister; and two outgroup taxa: V. gilvus, and V. plumbeus

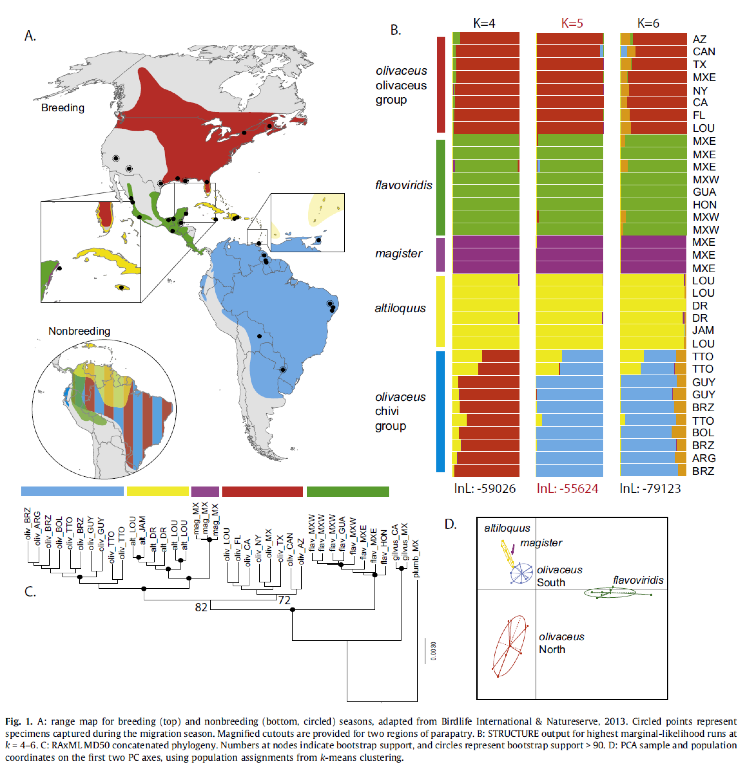

(Figure 1). They obtained genetic data following the ddRADseq

protocol, which resulted in a final dataset of 38 individuals with an average

of 13,323 loci per individual. They inferred a maximum likelihood phylogenetic

tree(RAxML v8) and a species tree (SNAPP v. 1.3). They also conducted

clustering analysis (STRUCTURE), Principal Components Analysis (Adegenet), and admixture analysis using D statistics.

Phylogenetic analyses revealed that northern

and southern olivaceus are

paraphyletic, with South American breeders more closely related to the

Caribbean taxa altiloquus and magister than to their North American

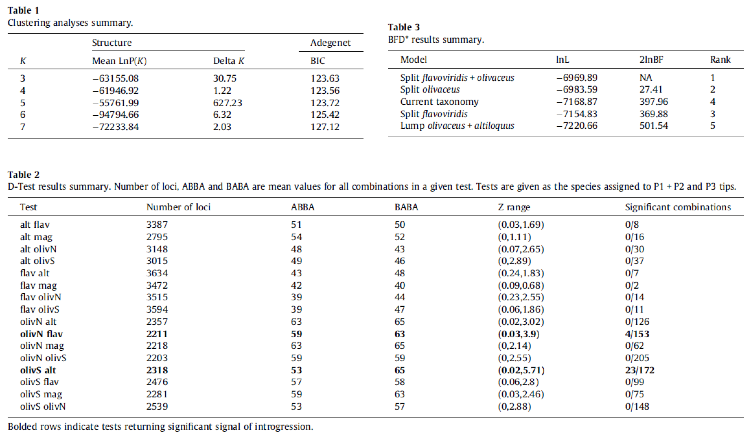

conspecifics. The STRUCTURE analysis favored a five-population model (Table 1)

that split northern and southern olivaceus.

It should be noted that both clustering analyses, STRUCTURE and Adegenet, showed a tendency to lump northern and southern olivaceus when run at k = 4.

D statistics did not support significant

introgression between northern and southern olivaceus

populations. The Bayes factor delimitation analysis favored the models that

split northern and southern olivaceus

(Tables 2 and 3).

Battey and Klicka (2017) concluded that olivaceus includes two genetically

divergent lineages breeding in disjunct ranges. Life history, in addition to

genetics, also supports splitting the species. Northern (olivaceus) and southern (chivi)

populations are non-monophyletic, do not exchange genes, and have different

direction and timing of migration, which are heritable life-history traits and

confer reproductive isolation between the groups. The authors propose elevating

the chivi group (all populations

breeding in South America) to species status under the English name Chivi

Vireo, based on the scientific name.

Recommendation:

We recommend splitting Vireo olivaceus into two species.

North

American populations: Vireo olivaceus,

Red-eyed Vireo

South

American populations: Vireo chivi,

Chivi Vireo

Literature Cited:

American Ornithologists' Union.

1998. Check-list of North American birds. 7th edition. Washington, D.C.:

American Ornithologists' Union.

Battey, C. J. and J. Klicka. 2017.

Cryptic speciation and gene flow in a migratory songbird species complex:

insights from the Red-Eyed Vireo (Vireo olivaceus). Molecular

Phylogenetics and Evolution113:67-75.

Cimprich, D. A., F. R. Moore, and M. P. Guilfoyle. 2000. Red-eyed Vireo (Vireo olivaceus). The Birds of North America (P. G. Rodewald, Ed.). Cornell

Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, NY. https://birdsna-org.libproxy.berkeley.edu/Species-Account/bna/species/reevir/

Johnson, N. K. and R. M. Zink.

1985. Relationships among Red-eyed, Yellow-green, and Chivi vireos. Wilson

Bulletin 97:421-435.

Ridgway, R. 1904. The birds of

North and Middle America. Bulletin of the U.S. National Museum, no. 50, part 3.

Slager, D. L., C.J. Battey, R. W.

Bryson Jr., G. Voelker, and J. Klicka, 2014. A multilocus phylogeny of a major

new world avian radiation: the Vireonidae. Molecular Phylogenetics and

Evolution 80:95-104.

Submitted by: Rosa Alicia Jiménez and Carla Cicero, Museum

of Vertebrate Zoology (to SACC February 2021)

Comments from Remsen [this is what I wrote on the NACC

proposal]:

“YES. The conclusions assume that

all South American vireos are part of the V. chivi complex. As noted in the paper, the V. chivi

group consists of highly migratory and totally sedentary subspecies, the latter

largely restricted to riverine habitats (and thus the range map in the paper

vastly over-states the actual range and especially the continuity of the

breeding distribution). Yet the paper

treats this complex as a monolithic unit based on what looks like only 9

geographic samples from what appears to be no more than 4 subspecies (for some

reason I cannot access Table 1 in Supplemental Material), none of them from

northwestern South America, where 4 unsampled subspecies also include isolated

trans-Andean caucae and griseobarbatus. Thus, the taxon-sampling failed to include

the majority of diversity in the complex (although Dave Slager’s

paper covers this better). The

assumption that these are all to closer nominate chivi than anything

else is probably safe but rests on traditional but untested boundaries in the

complex. So, I worry. The conclusion (that olivaceus is

paraphyletic with respect altiloquus depends entirely on one node in

Fig. 1C, and yet the support for monophyly of the morphologically uniform olivaceus

group is weak. Finally, altiloquus

itself consists of 6 subspecies, of which no more than 2 were sampled.

So,

I asked Mike Harvey for an assessment of that node, and his response (quoted

here with permission) soothes my reservations:

“First off, I would perhaps put less stock in the concatenated tree

than the STRUCTURE results and perhaps the SNAPP tree. As you know, trees from

concatenated genes can produce wonky results when gene trees are heterogeneous.

We have reason to expect the gene trees in this case are heterogeneous, both

because the mtDNA tree differs dramatically from the nuclear trees (suggesting

at least some past horizontal gene flow) and because the nodes in the

concatenated tree that are poorly supported are near each other deep in the

tree, suggestive of mixed signals due to competing topologies in that part of

the tree. However, although the likely explanation for those low support values

is ancient hybridization, this occurred well in the past and I don't think it

in any way indicates that northern and southern olivaceus are not

distinct. The STRUCTURE results suggest no recent admixture between the two

populations, and the SNAPP tree suggests they aren't sister at most of the

genome. Given strong support for the monophyly of (S olivaceus+altiloquus+magister)

in both concatenated and SNAPP trees, I doubt there has been any admixture

between the two olivaceus populations since olivaceus split from altiloquus and

magister, thus they are unlikely to be sister at any part of the genome.

The only small caveat here is that the sample sizes of individuals aren't huge,

although they aren't horrible either. I doubt the inferences about olivaceus

would change even with more individuals.”

Also, note that treating V.

gracilirostris as a species likely makes broadly defined V. chivi a

paraphyletic taxon

Comments

from Lane:

“A reluctant YES. The Harvey assessment of the trees

seems to support the age of the split of North American Vireo olivaceus and

South American V. chivi groups, but as noted by Van, it is

incredibly frustrating that Battey and Klicka (2017) ignored samples from along

the Amazon and NW South America (despite there being plenty of samples

available!). These populations would be very informative to include if only to

see what structure they would add to the chivi clade. The Slager et al

(2014) tree uses more samples, but has some strange and conflicting tree

topologies with respect to the monophyly of V. flavoviridis and

all remaining forms of the "V. olivaceus" clade!

“The morphology and voices of the populations of Vireo chivi

I know suggest that there is far more to the story than just splitting V.

olivaceus into two species and being done with it. Indeed, populations

currently considered nominate "chivi" are quite variable

themselves (leading me to wonder how many unrecognized taxa there are?). The

type locality of chivi is western Paraguay (not SE Brazil, as I would

have guessed, which is actually subspecies diversus), and thus the name

is probably best applied to the migratory population of the drier interior

Chaco and Chiquitano woodlands and nearby Andean foothills of Paraguay,

Bolivia, and Argentina. There are populations farther west in intermontane

valleys that are variably migratory (particularly in the more deciduous

valleys) and resident (in more humid valleys such as the Urubamba at Machu

Picchu) that are generally considered "chivi" for lack of any

additional names. Interestingly, to my ears, songs differ strongly between

birds from Santa Cruz, Bolivia, and birds east into Brazil (Minas Gerais and

Sao Paulo, which share a rapid quavering character in song elements with Santa

Cruz), and those that breed in deciduous forests of La Paz, around Machu

Picchu, and the deciduous valley of the Mantaro farther north in Peru. The

resident solimoensis of the main Amazonian

tributaries is comparatively distinctive again, giving a particularly slow

paced song with little variation in song elements. Interestingly, I think most

South American forms differ from Nearctic-breeding olivaceus in having

less diversity and complexity in song elements and generally slower delivery of

notes, although this appears not to be the case for the two forms from NW Peru

and S Ecuador (which sound much more like V. flavoviridis fide

Moore et al.'s Ecuador bird song DVD). I'd be interested to know if others

familiar with singing South American birds have noticed the same?”

Comments

from Areta:

“YES. I agree with concerns expressed by Van and Dan. Although there is more

complexity in South America than what available studies show, it seems

untenable to keep olivaceus and chivi as part of the same species.

Whether the remainder of South American "Chivi" vireos really belong

to the Chivi-group and whether more species can be recognized remain as open

tasks. The situation in Ecuador and Peru (with cis and trans Andean

populations, lowland resident, northern and southern migrants, including taxa griseobarbatus, solimoensis, pectoralis, olivaceus and

chivi) seems particularly complex and

begs for more rigorous studies of seasonality, vocalizations and genetics (see

for example Ridgely & Greenfield 2001 Volume 1, and Schulenberg et al.

2007).”

Comments

from Bonaccorso:

“YES. It makes sense a lot of sense from the

genetic data; these clades are not even monophyletic! These data, together with

the information about the natural history of these broad groups, complete the

picture of two different lineages. I agree that there is a lot of additional

complexity in South America, but I doubt it will mean reverting this change. We

just need a better understanding of diversity within Vireo chivi.”

Comments

from Stiles:

“YES, the split V. chivi from V. olivaceus, clearly justified by

the genetic data. That the data presented might miss differentiation in the chivi

group is another story, but genetic samples (or recently-taken specimens

for toepads from several countries, including Colombia, are available, so

enough material is available for the asking to do a decent job of writing the

next chapter!”

Comments

from Claramunt:

“YES. The genetic evidence is convincing, in

particular the fact that olivaceus and chivi are not even sister

species.”

Comments

from Robbins:

“YES,

based on the Battey and Klicka genetic data, this is a straightforward decision

for recognizing olivaceus as a separate species from chivi.

However, as all of us know who have worked across the SA continent, there are

very likely more cryptic species to recognize within chivi. This is a

first step.”

Comments

from Pacheco:

“YES. Although the sample coverage of the work is not

as wide as it could be, I am of the opinion that the molecular data are consistent

with the treatment of two species/two lineages.”

Comments

from Jaramillo:

“YES, it is a start. I would think the migrant vs

resident populations are going to show some interesting dynamics. They look

visually quite different as well, although I have only seen a few of the

residents.”