Proposal (908) to South

American Classification Committee

Split

Barn Owl (Tyto alba) into three species

Note from Remsen: Below is a proposal that was rejected by NACC and is posted here

with permission from its authors. If it

passes, it would change the classification of our species to: American Barn-Owl

(Tyto furcata).

Background:

Taxonomic references currently recognize from

one to four species in the Barn Owl (Tyto

alba) species complex. The AOS recognizes one cosmopolitan species (AOU

1998), as does HBW, which additionally groups 28 subspecies into eight species

groups (del Hoyo & Collar 2014). Clements et al. (2016) differentiate T. deroepstorffi (Andaman

Islands) from T. alba, whereas the

Howard and Moore Checklist recognizes three species: T. alba, T. deliculata, and T.

deroepstorffi (Dickinson & Remsen Jr. 2013).

The IOC (Gill & Donsker 2018) recognizes four species of barn owl:

· T. alba (Western Barn Owl), 10 subspecies, widespread in Africa and Europe

· T. furcata (American Barn Owl), 12 subspecies, widespread in North, Middle, and

South America

· T. javanica (Eastern Barn Owl), 7 subspecies, distributed from south and

southeast Asia to Australasia and southwestern Pacific

· T. deroepstorffi (Andaman Masked Owl), from the Andaman Islands

A different subset of three allopatric species

has been recognized based on molecular phylogenies derived from sequences of

the mitochondrial cytb gene and the

nuclear RAG-1 gene (Wink et al.

2009): the Common Barn Owl, T.alba, which has ten subspecies distributed in Africa,

Eurasia, and South-east Asia; the American Barn Owl, T.furcata, with at least five

subspecies from North, Central, and South America; and the Australian Barn Owl,

T. deliculata,

with at least four subspecies restricted to the easternmost part of Southeast

Asia, Australia, New Zealand, and Polynesia (Alibadian

et al. 2016). Morphological traits such as overall size, plumage coloration and

pattern, amount of feathering on the tarsus, and power of tarsus and toes have

been proposed to correlate with the three-species subdivision (Alibadian et al. 2016).

New Information:

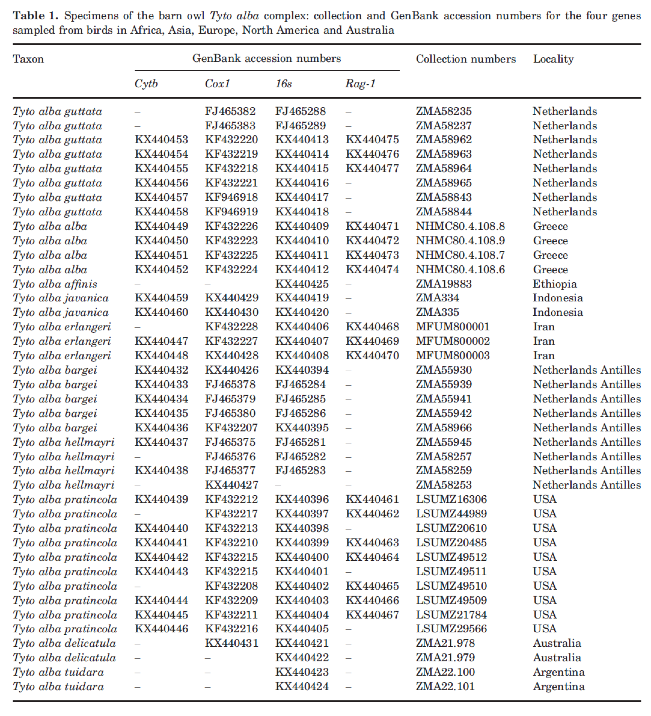

Alibadian et al. (2016) published a molecular study of systematic relationships

within the Barn Owl species complex, and estimated the timing of divergence

events. Alibadian et al. (2016) analyzed 40 samples

belonging to ten taxa, which included populations distributed across the world

(Table 1). They obtained sequences of three mitochondrial genes, cyt b (620

bp), CO1 (660 bp), 16S (568 bp), and one nuclear gene, RAG-1 (990 bp). They

inferred a maximum likelihood phylogenetic tree (RAxML v. 7.0.4) and a Bayesian

inference tree (MrBayes v. 3.2). They also conducted a molecular dating

analysis (BEAST v. 1.8), an estimation analysis of the ancestral distribution

of the three groups (LAGRANGE), and statistical analyses of ecological niche

overlap (MAXENT v. 2.0, ENMTOOLS).

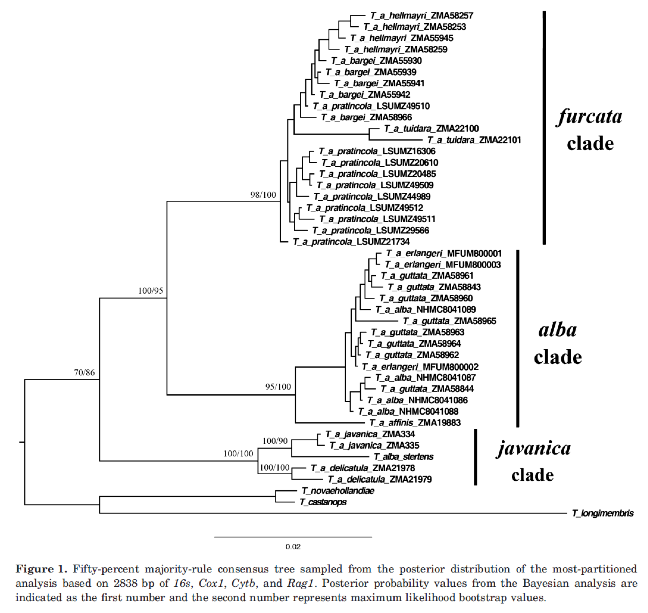

Phylogenetic analyses revealed three main

clades with strong geographic structure. The first group, the furcata clade, included subspecies from

mainland North and South America and Curaçao (T. a. pratincola, T. a. hellmayri, T. a. tuidara,

T. a. bargei). The second group, the alba clade, included subspecies from the

Netherlands, Greece, Iran, and Ethiopia (T.

a. guttata, T. a. alba, T. a. erlangeri, T. a.

affinis). The third group, the javanica

clade, contained samples from Indonesia, India, and Australia (T. a. javanica, T. a. stertens,

T. a. deliculata) (see tree below). The dating

analysis indicated that the Barn Owl complex originated during the Middle

Miocene, and the biogeographical reconstruction suggested an origin in the Old

World. A low amount of ecological niche overlap was estimated among all three

lineages.

Alibadian et al. (2016) proposed that the taxonomy of Tyto alba be redefined and that at least three species should be

recognized. However, because not all T.

alba subspecies were included in the study, the authors established the

species limits based mainly on the geographic distribution of the subspecies

sampled. The authors proposed restricting the specific epithet alba to populations from the

Afrotropical and Palearctic regions to at least eastern Iran. They suggested

elevating the furcata clade

(populations from Nearctic and Neotropical regions, including at least part of

the Caribbean) to species status under the name Tyto furcata. The javanica clade,

including populations from Indonesia, India, and Australia (T. a. javanica, T. a. stertens,

T. a. deliculata), was proposed for elevation

under the name Tyto javanica, because

the name javanica has priority over deliculata.

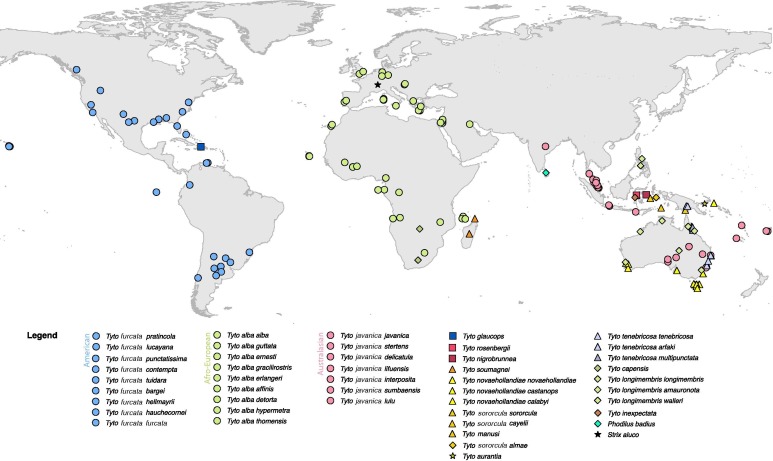

Uva et al. (2018) published another molecular study of the systematic

relationships of the barn owls and relatives, estimated divergence times using

fossil calibrations, and reconstructed ancestral ranges. Uva

et al. (2018) analyzed 179 genetically different individuals belonging to 16

species of Tyto and 1 species of Phodilus, which

included over 30 subspecies distributed worldwide (see map below). They

obtained sequences of five mitochondrial markers (ND6, CO1, control region,

cytochrome b, and 16S) and two nuclear markers (C-MOS and RAG-1). They inferred

maximum likelihood phylogenetic (RAxML) and Bayesian inference trees (BEAST v.

1.8.4) and constructed a haplotype network of the Common Barn Owl based on the

cyt-b sequences (TCS, POPart).

Figure 1. Sample location map - sample

locations, legend following the classification of Gill and

Donsker (2018). When samples were missing precise locations, approximate

coordinates were given.

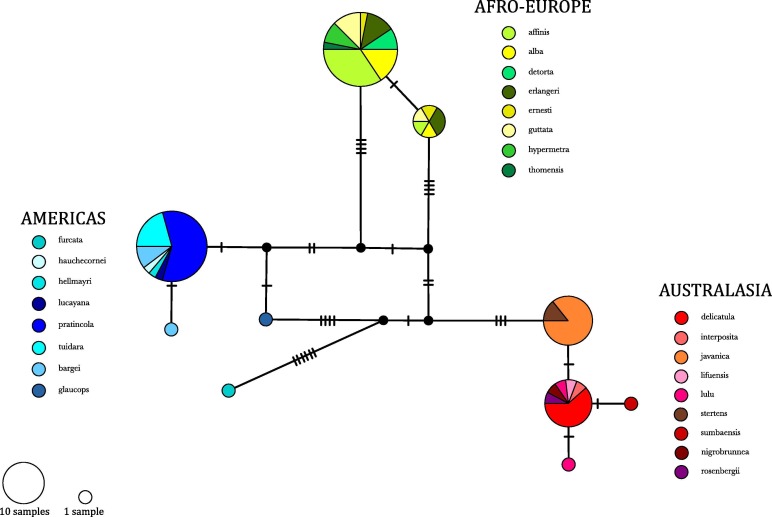

Phylogenetic and haplotype network analyses

(Figure 3) recovered three main lineages within the Common Barn Owl group,

which differed by 5.82 to 9.33% in cyt-b sequence, supporting the results from Alibadian et al. (2016). The scientific and common names used

by Uva et al. (2018) followed the IOC World Bird

List.

· Australasian clade: samples of the Eastern Barn Owl, T. javanica, from Australia and

Indonesia, including the Sulawesi Masked Owl, T. rosenbergii, T. javanica from India, Malaysia and Java, and T. nigrobrunnea.

· American clade: samples of the American Barn Owl T. furcata, and the Ashy-faced Owl, T. glaucops. This group also includes a subclade of two island

endemics from Galapagos (T. f.

punctatissima) and Hispaniola (T. g.

glaucops).

· Afro-European clade: samples of the crown group of all Western Barn

Owls, T. alba, and the São Tomé Barn

Owl, T. a. thomensis.

Figure 3. Genetic structure within

the Common Barn Owl group, including all taxa nested within the three major

clades - TSC haplotype networks drawn for cyt-b sequences, following the

classification in Gill and Donsker (2018).

The dating analysis indicated that the Barn

Owl complex originated during the Late Miocene (ca. 6 mya). The biogeographical

reconstruction suggested an origin in the Australasian and African regions.

Uva et al. (2018) concluded that the Common Barn Owl consists of three

evolutionary units, as in Alibadian et al. (2016),

and indicated that three species should be recognized:

· African and European populations: Tyto

alba, Western Barn Owl

· North, Cental and South American

populations: Tyto furcata, American

Barn Owl

· South and southeastern Asian and Australian populations: Tyto javanica, Eastern Barn Owl

Recommendation:

We recommend splitting Tyto

alba into three species to better reflect the evolutionary trajectory of

the clade. The phylogenetic evidence suggests geographic and genetic isolation

of the three lineages (Wink et al. 2009, Nijman & Alibadian

2013, Alibadian et al. 2016, Uva

et al. 2018), in addition to their correlated morphological traits (Alibadian et al. 2016).

(1)

Afrotropical and Palaearctic populations: Tyto

alba, Western Barn Owl

(2) American

populations: Tyto furcata, American

Barn Owl

(3) Eastern

Asian and Australian populations: Tyto

javanica, Eastern Barn Owl

The recommended English names are based on

those proposed by Uva et al. (2018), which are

currently used by the IOC World Bird List (Gill & Donsker 2018).

Literature Cited:

Alibadian M., N. Alaei-Kakhki, O. Mirshamsi,

V. Nijman, and A. Roulin. 2016. Phylogeny,

biogeography, and diversification of barn owls (Aves: Strigiformes). Biological Journal of the Linnean Society

119, 904-918.

American Ornithologists' Union. 1998. Check-list

of North American birds. 7th edition. Washington, D.C.: American

Ornithologists' Union.

Clements J. F., T. S. Schulenberg,

M. J. Iliff, D. Roberson, T. A. Fredericks, B. L. Sullivan, and C. L. Wood.

2017. The eBird/Clements checklist of birds of the world: v2016. Downloaded

from http://www.birds.cornell.edu/clementschecklist/download/

del Hoyo J., and N.J. Collar.

2014. HBW and BirdLife International Illustrated Checklist of the Birds of the

World, Volume 1 Lynx Edicions in association with BirdLife International,

Barcelona, Spain and Cambridge, UK.

Dickinson E.C., and J. V. Remsen

Jr. 2013. The Howard and Moore Complete Checklist of the Birds of the World –

Volume 1 Non-Passerines. Aves Press, Eastbourne, UK.

Gill F., and D. Donsker. 2018. IOC

World Bird List (v 8.1), DOI: 10.14344/IOC.ML.8.1.

Nijman V., and M. Alibadian. 2013. DNA barcoding as a tool for elucidating

species delimitation in wide-ranging species as illustrated by owls (Tytonidae

and Strigidae). Zoological Science 30,

1005-1009.

Uva V., M. Päckert, A. Cibois, L. Fumagalli,

and A. Roulin. 2018. Comprehensive molecular

phylogeny of barn owls and relatives (Family: Tytonidae), and their six major

Pleistocene radiations. Molecular

Phylogenetics and Evolution. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ympev.2018.03.013

Wink M., A. A. Elsayed,

H. Sauer-Gurth, and J. Gonzalez. 2009. Molecular

phylogeny of owls (Strigiformes) inferred from DNA sequences of the

mitochondrial cytochrome b and the nuclear RAG-1 gene. Ardea 97, 581-591.

Submitted

by: Rosa Alicia

Jiménez and Carla Cicero, Museum of Vertebrate Zoology (to SACC in February

2021)

Comments from Remsen

[this is what I wrote on the NACC proposal]: “--- NO!!! It’s great to see this

proposal because we really need to evaluate all this given the new data, and

IOC and HBW splits. However, this split

is based on degree of genetic divergence of (presumably) neutral loci. It is homologous to bar-coding rationale. Because genetic divergence is measured on a

continuous scale, there is no conceptual basis for calling a split “deep” or

“shallow” or whatever. Yes, there are

three lineages, not surprising for such a widespread species, but are there any

consequences relevant to BSC species limits in the divergence at neutral

loci? Otherwise, all we would be doing

is instituting subjective thresholds on genetic differentiation of loci that by

definition are assumed to be irrelevant to the biology of the birds

involved. The morphological traits said

to be associated with each lineage are interesting but as far as I can tell

just geographic variation largely irrelevant to species limits.

“I cannot think of a single

modern analysis of species limits in any owl (or caprimulgid) that isn’t

anchored in vocal differences. Barriers

to free gene flow are exceptionally strongly correlated with vocal differences

in nocturnal birds. It is widely known

that plumage differences are basically irrelevant in these nocturnal birds (for

obvious reasons, including that some species have strikingly different color morphs). So, how can a proposal in 2018 NOT

concentrate on voice? Until vocal

differences, if any, are elucidated, we shouldn’t even be considering this

split in my opinion, for the reputation of our Committee.

“Not one YES voter has produced a coherent rationale for this split;

some have written that the in press paper (with first and last names of authors

reversed, and at least two run-on sentences … typical MPE) that tipped

the scales, but did not explain why.

Vera et al. presented great data on relationships among Tyto,

with much broader taxon-sampling than the previous paper. However, their taxonomic conclusions are

weakly supported and probably would not have survived a bird journal

review. It’s basically a set of gene

trees, combined, and as stated clearly by the authors, the paraphyly is driven

by mtDNA: “our tree

topology is largely dominated by the signal of mitochondrial markers”. The authors themselves noted: “All these pitfalls have to be kept in mind

for any taxonomic conclusions drawn from newly established phylogenetic

hypotheses in the following, because gene-tree topologies depend on the

combined effects of introgression, incomplete lineage sorting and faulty

taxonomy.” Further, the paraphyly itself is the consequence of

peripheral speciation: three insular taxa currently ranked as species (our

T. glaucops, T. nigrobrunnea from the Sula Islands, T. rosenbergii from Sulawesi). If these insular spinoff taxa did not exist, Then

There Would Be No Paraphyly. For

this and other reasons, use of the monophyly criterion at the population level

is a misapplication of Hennigian principles; Hennig

himself did not use the term monophyly at the species level because, using an

early schematic diagram of incomplete lineage sorting, he showed why species

are not necessarily monophyletic.

“The most interesting finding is that the distinctive T. a.

punctatissima from the Galapagos is the likely sister of Hispaniolan T.

glaucops (yet another Galapagos-Gr. Antilles connection), and in my

opinion, requires a proposal to split punctatissima. Otherwise, all we have is three lineages

corresponding to three major areas.

“The authors’ rationale for the split of Barn Owl into three species is

based (in addition to the paraphyly that they themselves were cautious about)

on the existence of three monophyletic lineages corresponding to three major

regions. This is a typical pattern that

provides no basis for assigning taxon rank.

Although I can’t seem to find where in the text the authors present the

actual genetic distances among them (presented in an unavailable table in

online supplementary material), it is clear that the reasoning is basically

bar-coder rationale. For example, they

regard the split of Osprey into four species as a given because they are

genetically “well-differentiated species”, when the actual % sequence

divergences (1.5-2.6% in Monti et al. 2015) are small; these would be at the

low end of % sequence divergences among populations of Andean or Amazonian

birds separated by rivers.

“The plumage differences among the populations are minor, and perhaps

less than those among subspecies within the three major groups. Regardless, plumages in owls are essentially

meaningless in terms of species limits.

Owls are notorious for color phases, geographic variation, and

individual variation that are not considered relevant to species limits. I think there might be more individual

variation in Glaucidium brasilianum than among these Barn Owl

populations.

“What about voice? A cruise

through what I can find on xeno-canto indicates that the eerie hissing screech

that we are all familiar with in our Barn Owl is also the primary vocalization

of European birds (“Western Barn-Owl”):

England: https://www.xeno-canto.org/186611

Belgium: https://www.xeno-canto.org/235525

Netherlands: https://www.xeno-canto.org/384166

“African birds (also “Western Barn-Owl”) sound similar:

Senegal: https://www.xeno-canto.org/237647

“So do Indian birds (“Eastern Barn-Owl”), at least superficially:

India: https://www.xeno-canto.org/species/Tyto-alba?pg=3

“And just so you know, here’s a

recording from distant Argentina, which sounds to me just like those here in

the USA: https://www.xeno-canto.org/species/Tyto-alba?pg=3

“Perhaps an actual formal analysis would find some consistent,

diagnostic differences among these complex screeches, but the burden-of-proof

in my opinion is showing the differences.

Then, do the differences make a difference to the owls themselves? At the other potential extreme, maybe all Tyto sound alike. If that’s the case, then this needs to be

addressed explicitly.

“Finally, if this proposal somehow passes (despite

not a single committee member explaining why it should), a separate proposal on

English names should be required: is “American Barn-Owl” really the way we want

to go for a species found throughout the Western Hemisphere? Sure, Europeans regard all that as “the

Americas”, but it makes me queasy.

Eastern and Western are out of our purview, but are to be lackluster in

the extreme.

Comments

from Lane:

“NO. I think Van makes some very important points in

his review of the situation here. Overall, I find such genetically driven cases

unconvincing for splits without further correlating characters to back them up.

Voice, as Van points out, seems an obvious character set for a nocturnal group

of birds. That said, I must admit that I am unable to detect an obvious

distinction in the voices of T. "alba" and T. glaucops

(but the latter has only 2 available recordings--of the same individuals--on

XC), two populations we *know* must be acting as good species, given that they

are sympatric on Hispaniola! Of course, Tyto owls seem to have

relatively few useful characters to score in their voices (listening to various

other Tyto on Xenocanto reveals Van's fear:

they pretty much all sound similar), and even being certain of using homologous

vocalizations is difficult (to me, at least). In light of this relative lack of

support of other characters to back up the split up of Tyto alba,

I vote NO.”

Comments

from Areta:

“YES. The genetic evidence shows fairly deep breaks (even deeper than those

between other recognized species of Tyto)

with overall good geographic coverage. As for the voices, I will echo here what

a NACC member wrote in voting on this proposal. Magnus & The Sound Approach

(2015, p. 17; if anyone wants to read it, I have the book) state the following:

‘By contrast, there are

dramatic differences between Common and American Barn Owls. American has much

shorter perennial screeches, typically less than a second long, and in a wide

range of recordings, I have never heard American giving anything remotely like

a courtship screech. Gerrit Vyn is the author of an

excellent CD on North American Owls (2006). When I sent him an example of Common

Barn Owl courtship screeches, he confirmed knew nothing similar from American.

This not only supports separating the two species but also the two kinds of

screeches.’

“At the same time, American Barn Owl has a prominent flight call that is

completely absent in Common Barn Owl. It was Gerrit who recorded the metallic

clicking sound in CD1-06,

which he calls the 'kleak-kleak’' call (Vyn

2006). Unpaired males use it most often (Gerrit Vyn

pers comm), so it must have an important role in mate attraction. Marti et al

(2005) reported that males kleak

in the vicinity of the nest, soon after leaving the daytime roost,

and when approaching with food deliveries. Several other Tyto have similar calls (e.g.,

African Grass Owl T. capensis,

Eastern Grass Owl T. longimembris and Australian Masked Owl T. novaehollandiae). So

rather than being an American invention it seems that Common stopped using this

call and replaced it with courtship screeching."

“The

"kleak-kleak"

is also a common vocalization of birds across Argentina, and it seems

impossible that such a prominent vocalization would have gone undetected within

the range of Common Barn Owl (T. alba

sensu stricto); The Sound Approach would have detected it if it indeed

occurred.

“This

marked vocal differentiation, coupled to genetic data, places the burden of

proof in those willing to maintain the status quo.

“As

for the common English name, American Barn Owl looks good to me. I am American

because I was born and raised in Argentina, much as Tyto furcata tuidara are American.

“The situation with T. glaucops and punctatissima is potentially more complex, and more evidence would

be necessary to make the split (or lump?). However, the proposal does not deal

with this case. This is what Uva et al. (2018) said

about this, which is conservative and reasonable:

"In the American Barn Owl, T. furcata,

we found no differentiation between North, Central and South America.

Phylogeographic structure was only detected between a clade of two insular

taxa, T. g. glaucops from Hispaniola and T. f.

punctatissima from the Galapagos Islands, which were sister to the

remaining continental and insular American Barn Owls. The extreme disjunct

distribution of these sister taxa is even more surprising than those of masked

owl endemics from islands east and west of New Guinea, and given the poor node

support (0.77 PP/66 BS) putative genetic distinctiveness of Caribbean and

Pacific populations needs further confirmation from future phylogeographic

studies. For the time being, a species-level split of T. furcata

from T. alba and T. javanica as previously

advocated by some authors (Aliabadian et al., 2016;

Gill and Donsker, 2018) seems justified, keeping in mind that phylogenetic

relationships of T. f. punctatissima and T. glaucops

are still unclear. Genetic information on the dark island forms from Puerto

Rico (T. glaucops cavatica) and

from the Lesser Antilles (T. g. nigrescens, T. g.

insularis) missing to date are needed for a concise species-level

classification of the American Barn Owl, T. furcata (sensu Gill

and Donsker, 2018) and the Ashy-faced Owl, T. glaucops."

“I want to note that

the problem of what to do with punctatissima

will remain open regardless of whether we split furcata or not. So, I

favor recognizing Tyto furcata as a

separate species, it seems difficult to withhold from this given the vocal and

genetic differences with Tyto alba.

“Additional references:

Robb, M. & The

Sound Approach. 2015. Undiscovered owls, A Sound Approach guide. The Sound Approach.”

Comments

from Bonaccorso:

“YES. After reading Nacho´s comment, I am more

convinced, but we have to admit that if there are voice differences between

these three lineages, the evidence is anecdotal. I agree that neutral-marker

differences (which are pretty high in this case) are not enough to infer

reproductive isolation. However, in a bird with apparently such good dispersal

abilities (think about the islands they have reached), a few dispersal events

between lineages in the last few thousand years would be enough to show

admixture, don´t you think?”

Comments

from Stiles:

“YES to splitting furcata from asio (and javanica) as the

American Barn Owl. The vocal data (especially in a genus like Tyto not

noted for vocal variation, clearly tip the burden of proof onto those

maintaining a single species. The sympatry of furcata and glaucops on

Hispaniola clearly merits attention as well, although as I understand it, there

are no genetic data for it. However, the documentation of two or more recently

extinct species of Tyto in the Antilles indicates an appreciable

radiation of barn owls in the Caribbean, of which glaucops and the subspecies

of it, if not themselves genetically distinct, represent the last survivors of

this radiation.”

Comments

from Claramunt:

“YES. As pointed out by others, the situation is complicated, and

there is some critical information missing, in particular, information from

nuclear markers is muted, and it is not clear how the phenotypes sort with

respect to the genetic data. However, accepting that the major mtDNA clades

represent lineages, the study shows that furcata is sister of

Hispaniolan T. glaucops (including punctatissima), not of T.

alba, and knowing that, we should not retain furcata and alba

together to the exclusion of glaucops. Otherwise, relationships would be

misrepresented.

“Furthermore, If T. glaucops and T. furcata, being

so similar in plumage and vocalizations and with 2 million years of divergence,

are already reproductively isolated, that suggests that T. furcata and T.

alba, also similar in plumage and vocalization but with 4 million years of

divergence, may also be reproductively isolated. What do we know about how

these owls maintain reproductive isolation (or not)? Similarities in vocalizations

doesn’t seem to matter much. So, I think that the genetic evidence on actual

relationships trumps speculations about reproductive compatibility in this

case.”

Comments

from Schulenberg:

“As it happens, I visited both Europe and Africa before I ever set foot in

South America. So within just a few years, my birding horizons expanded from

one continent to two continents, three continents, four. Right away I began

keeping track of the species that I had seen on multiple continents. But over

time, those lists began to shrink, not expand, due to taxonomic reassessments.

In a few cases this happened even for species that breed only at high latitudes

(e.g., Velvet Scoter Melanitta fusca and White-winged Scoter Melanitta

deglandi). But the more general trend was of splits that affected species

that were widespread at mid-latitudes, such as Little Tern Sternula

albifrons and Least Tern Sternula antillarum; Kentish Plover Charadrius

alexandrinus and Snowy Plover Charadrius nivosus; Eurasian Magpie Pica

pica and Black-billed Magpie Pica hudsonia;

Eurasian Wren Troglodytes troglodytes, Pacific

Wren Troglodytes pacificus, and Winter Wren Troglodytes hiemalis;

Eurasian Treecreeper Certhia familiaris and Brown Creeper Certhia

americana; and perhaps others that I've forgotten. Viewed in that light,

the possibility that Old and New World barn owls might be separate species does

not seem at all outlandish to me, indeed it seems more likely than the odds

that they're conspecific. So it's well worth keeping an open mind about this

prospect, of course while also searching for additional evidence that would

bear on the question.

“Van

kicked things off by comparing audio recordings of barn owls from various parts

of the Old and New worlds, and came away unimpressed. Dan has a good point,

however, that comparing screeches within the Tyto alba complex only gets

one so far: perhaps one needs a yardstick from elsewhere in the genus for

calibration. To me a broader question here is how well do we understand the

functions of barn owl screeches, and how certain we can be that we're comparing

homologous vocalizations?: these may be a lot trickier to evaluate than, say,

pygmy-owl songs.

“So

one needs a truly deep dive into barn owl vocalizations. Therefore I applaud

Nacho for again calling attention to the discussion in Undiscovered Owls. To

amplify on the piece that Nacho quoted, Robb and The Sound Approach (RATSA)

define the 'perennial screech' as, at least in Europe, 'the ... sound we hear

most often throughout the year'. This is contrasted to a 'courtship screech',

which is seasonal ('peaks during the weeks leading up to egg-laying'), usually

is longer than the courtship screech, usually is given when perched (not in

flight), and differs in a few other parameters (pace, smoother rise in pitch

and volume, etc.). RATSA's take is that the courtship screech is lacking in

American populations. Perhaps the clicking call of North American birds –

something not given by European barn owls - is a homologous vocalization,

perhaps not. In any event, RATSA identify what seem to be significant

differences in the vocal repertoire between American and European members of

the barn owl complex. As noted by Nacho, someone brought this up when this

proposal was before NACC. (I don't know who that was, by the way, but perhaps

Jon Dunn?) I also don't know how much discussion this generated within NACC,

but disappointingly little is reflected in the comments posted online. To me, these vocal

differences are pretty compelling evidence for a split. It's fine to disagree,

if anyone can articulate why you don't find this to be convincing; but simply

ignoring RATSA's take on barn owl vocalizations should not be an option.

“As

far as issues of paraphyly are concerned, discussion to date has focused

mostly, and narrowly, on Tyto glaucops. As background, keep in mind that

early North American taxonomists had no trouble in recognizing New World barn

owls as a separate species from Old World Tyto alba, and also recognized

multiple species in the New World, including Tyto glaucops (e.g. Ridgway

1914, Cory 1918). Hartert (1929) and Peters (1940) later consolidated all taxa

into a single species. In the 1970s North American barn owls colonized

Hispaniola but did not interbreed with resident glaucops, leading to

recognition again of glaucops as a species. So we know that Hartert and

Peters underestimated species diversity among barn owls, but we don't know

whether they were off by just a little, or by a lot. Among other contenders for

species rank are:

• insularis (St. Vincent, Bequia,

Union, Carriacou and Grenada) and nigrescens

(Dominica): These taxa differ from mainland North American barn owls in many of

the same ways as does glaucops, but don't happen to be sympatric with

any other member of the genus. del Hoyo and Collar (2104) classify these as

subspecies of glaucops, despite the range disjunction. These were

recognized as a separate, polytypic species (Tyto insularis) by Ridgway

and Cory. Tyto insularis also was recognized by Suárez and Olson (2020),

based in part of differences in the skull. There are no genetic data on insularis

or nigrescens, nor any detailed analysis of their vocalizations.

• furcata (Cuba and Jamaica): This population

also seems to be pretty distinctive, with white secondaries and tail. It was not recognized

as a species by Ridgway or Cory, but is by Suárez and Olson (2020), again based

in part on osteological distinctions. Note that Uva

et al. included a sample identified as furcata that clusters within

North American Tyto; the relevant sample, however, appears to be a

sequence pulled from GenBank, with no reported locality information, so its

identification as furcata may be questioned, and may not be verifiable.

At the very least, the lack of precise locality for this sample is consistent

with their Figure 1, shows no samples from either Cuba or Jamaica.

• bargei (Curacao): Recognized

as a species by Ridgway and Cory; also accepted, without comment that I could

find, by Suárez and Olson (2020). Genetically, however, bargei

appears to be nested well within North American barn owls (see Aliabadian et al. 2016).

• punctatissima (Galápagos):

Recognized as a species by Ridgway and Cory. As noted by Van, the limited

genetic data (Uva et al.) suggests that it is not

conspecific with mainland North American barn owls. Steadman (1986) also

recognized punctatissima as a species, based on plumage differences and

its much smaller size; Suárez and Olson (2020) seem to concur.

Even

that is not all. Potentially relevant are a host of extinct taxa:

Tyto maniola (Cuba; Late

Pleistocene): a small species; see Suárez and Olson (2020).

Tyto ostologa (Hispaniola;

Quaternary): a giant barn owl; see Suárez and Olson (2015).

Tyto pollens (Bahamas, Cuba; Quaternary): a giant

barn owl; see Suárez and Olson (2015).

Tyto noeli (Cuba, Jamaica,

Barbuda; Quaternary): a giant barn owl; see Suárez and Olson (2015).

Tyto cravesae (Cuba; Quaternary): a

giant barn owl; see Suárez and Olson (2015).

To

recap, there are two widely recognized extant species in the New World

(mainland barn owls and Tyto glaucops); there is good reason to

recognize a third (punctatissima); there plausibly could be one or more

additional extant species; and there are at least five extinct species of New

World Tyto. We don't have a phylogenetic framework that encompasses all

of these taxa (especially of course for the extinct species). The odds of many

of these species resulting from independent colonizations of Tyto from

the Old World seem low, however. Whether each species in the Caribbean

radiation (extant and extinct) represents an independent colonization from the

mainland, or whether there was some in situ differentiation within the

West Indies, remains an open question. Regardless, clearly there has been a

significant New World radiation of Tyto; and it seems quite odd to me to

continue to try to shoehorn mainland North American populations into Tyto

alba while acknowledging not one but a host of New World island species.

And that's not to mention the vocal evidence, cited above, that strongly

suggests that New and Old World barn owls are separate species. This is not a

case, in other words, where we have contradictory information; instead,

multiple lines of evidence all point in the same direction, towards splitting

the barn owls.

Cory, C. B. 1918. Catalogue of birds of

the Americas. Part II, number 1. Field Museum of Natural

History Zoological Series volume 13, part 2, number 1.

del Hoyo, J., and N.J.

Collar. 2014. HBW and BirdLife International illustrated checklist of the birds

of the world. Volume 1. Lynx Edicions, Barcelona.

Hartert, E. 1929. On various forms of the genus Tyto. Novitates Zoologicae

35: 93–104.

Peters, J. L. 1940. Check-list of birds of

the world. Volume IV.

Harvard University

Press, Cambridge, Massachusetts.

Ridgway, R. 1914. The birds of North and Middle America.

Part VI.

Bulletin of the United

States National Museum 50, part 6.

Steadman, D. W. 1986. Holocene

vertebrate fossils from Isla Floreana, Galápagos. Smithsonian Contributions to

Zoology 413. https://doi.org/10.5479/si.00810282.413

Suárez, W., and S. L.

Olson. 2015. Systematics and distribution of the giant fossil barn owls of the

West Indies (Aves: Strigiformes: Tytonidae). Zootaxa 4020: 533–553. https://doi.org/10.11646/zootaxa.4020.3.7

Suárez, W., and S. L.

Olson. 2020. Systematics and distribution of the living and fossil small barn

owls of the West Indies (Aves: Strigiformes: Tytonidae). Zootaxa 4830: 544-564.

https://doi.org/10.11646/zootaxa.4830.3.4

Comments

from Jaramillo:

“YES. Thanks

to Tom for his extensive notes, as well as Nacho for the information, including

the valuable discussions in “A Sound Approach – Undiscovered Owls.”

“Look, I think that the way Barn

Owls use voice in courtship and territoriality is entirely different than in

typical owls. The screech vocalizations are difficult to compare, and there

seems to be a good amount of individual variation in screeches. Even so, in the

Americas there are at least two screech categories, a wider band one, and a narrower

band one. As well, one screech type ends in an upward inflection, almost like a

final accent. I don’t know what this means; however, you can listen throughout

Tyto, and find that it is difficult to hear much difference in

screeches of clearly different (often radically different looking populations,

some sympatric). Sometimes island populations seem to be the most distinct,

visually and vocally. In any case, the fact that so many species have similar

screeches, seems to me that similarity in screech is not a negative for

assessing species limits. Radically different vocalizations are much easier to

apply in a species limit context. But in short,

Tyto are

different than typical owls, and similarity in vocalizations is not all that

informative.

“The fact that the 'kleak-kleak’ call is present in New World

Tyto, and not in the European Barn Owl is huge. As Nacho points out,

this call is common in the New World, and I think it may be a courtship call as

I hear this voice most often in the breeding season, not so much in the winter.

We have Barn Owls commonly here where I live, and a neighbor has a nest box

that is sometimes used just three doors down, so I get to hear them frequently.

This call type is present in glaucops, and also

in insularis

(Lesser Antilles).

“In short, we have genetic data,

and vocal data that clarifies that American Barn Owl should be separated from

the European. By extension, I would separate the Asian-Australasian one as well

to be consistent. It is actually pretty crazy to think that this widespread

taxon would all be one single species. The more we look at Cosmopolitan

species, the more we realize that they are not a single species, and I am sure

we will have others in the future to contend with – Osprey, Great Egret etc.

“I would go further and suggest we

append this proposal to split punctatissima,

or perhaps I can write up a quickie proposal using much of the

data here to make that happen. I recall reading in one of the

Tyto papers how

they found it unusual that two island taxa from Hispaniola (glaucops)

and Galapagos (punctatissima) would be sisters, but this makes a lot of

sense. The connections between the Galapagos and the Caribbean are multiple,

and not only in birds but seemingly in invertebrates as well. There has been so

much work on speciation within the Galapagos, and evolution of forms in the

archipelago that this Caribbean connection has been somewhat lost in the

shuffle. To me separating the Galapagos taxon is clear cut, although we have

little information on it other than skins and photos. Let me assure you that it

is a radically different looking creature. There will be little to no new data

on voice for this species unfortunately. I have tried to get some, but have

never heard it. Similarly, the Galapagos Short-eared Owl is another which I

have not yet heard or recorded. The fact that the fossil record shows a varied

fauna of Tyto over the years is important. Many taxa in the Caribbean are

lineages which are old, and were likely widespread at one point, essentially

living fossils. The proposal that there may still be a greater diversity of

Tyto in the Caribbean/Galapagos is not unusual, it may even be

expected. Here is one Galapagos voice, and it is actually quite different.

Galapagos

https://www.xeno-canto.org/557834

“For the North American committee

it is a tad more complex in that insularis

is also radically different in look (rusty face, ferruginous

overall appearance), and is certainly allied to the

glaucops/punctatissima clade. It

gives the 'kleak-kleak’ calls, and the single screech

that I have heard and recorded was very different from any Barn Owl I have

heard. It seems to me that certainly this is another species, unless it is lumped

with glaucops. Tom’s

note today got me to find my recordings and photos and upload them to

eBird/Macaulay. I offer these to listen to, as they have some pertinence to glaucops/punctatissima. In short,

there are certainly multiple species within the New World, so I do not

understand why there is a reticence to separate the overarching three world

level clades within this context.

insularis

insularis

screech given from perch – St. Vincent (with photos)

https://ebird.org/checklist/S83671424

'kleak-kleak’ calls – Grenada, two

different versions.

https://ebird.org/checklist/S83671800

https://ebird.org/checklist/S83671803

'kleak-kleak’ calls from California for

comparison

https://ebird.org/checklist/S71415159

Additional

comments from Remsen: “At this point, I believe strongly that the

current proposal be tabled and that a new one be written. Actually, a better approach would be for all

this information to be compiled, synthesized, and published as a short

paper. Further, Alexandre Roulin, the world’s authority on the species complex, has

just written a book on barn owls. Roulin is an ecologist, not a systematist, but he has

published perhaps 100+ papers on geographic variation and function of color in

barn owls; I predict his new book will have data or information relevant to

species limits.

“At this point, if this proposal

passes, it will be based on our cumulative comments, not the proposal itself,

and I instinctively dislike that as a matter of procedure.

“As for the Barn Owl, here’s an overview

of the situation. The widespread

continental populations are surprisingly similar in plumage and weakly

differentiated. My read of the weak

genetic data is that New and Old World populations are much more similar

genetically, at least at nuclear loci, than are phenotypically similar

populations of many Amazonian and Andean birds across river barriers. Presumably, this similarity despite the

distance is maintained by dispersal.

Indeed, the Barn Owl sensu lato is certainly among the most remarkable dispersers

in the world. Vagrant records are

numerous; one even reached South Georgia! The propensity to colonize islands is

strong, and so there are numerous spin-off populations that differ from

continental populations to various degrees, likely depending on time since

arrival. Some of these have diverged to

the degree that recognition as separate species is obvious, others only weakly,

and many in between. With such a

tendency for peripheral isolates and rapid speciation, application of paraphyly

criteria to assigning species limits is problematic when comparing insular to

continental populations. What we have

are continental populations, closely related in terms of neutral loci, pumping

out peripheral isolates that then diverge to varying degrees while gene flow

still occurs, evidently, among continental populations, i.e. a situation that

doesn’t really fit the classic allopatric speciation model much less the

cladistic view of endless, clean dichotomous branching.

“Given what seems to be a large

repertoire of weird sounds, I think extra caution is needed when comparing

recordings. Maybe some of these calls

are diagnostically different between taxa, maybe not. How do we know? Without a rigorous analysis

of within-population and among-population variation of homologous vocalizations,

elevating any taxon to species rank or not based on a few recordings seems

unusually unwise, and we have used this very criterion to reject other

proposals on species limits.

“The NACC proposal did not cite “Robb

and the Sound Approach” likely because of lack of access. I’m not sure if I’ve ever seen a copy. At nearly $200 (i.e. in same price range as

an 800+ page, lavishly illustrated HBW volume), I wonder how many individuals

can afford it. The LSU Library, which

has one of the largest university bird libraries in the world, doesn’t have it

(or the Petrel book); I may try to get it the library to order it, although

like most public university libraries, we have budget problems. Thus, a new proposal would need to present

copies of what Robb actually says so that we can do a standard evaluation of

the statements therein in terms of what data support them.

“Although the worldwide distribution of

the Barn Owl certainly makes it a tempting target for taxonomic reassessment,

that sort of distribution itself does not necessarily demand a change in

species limits. The track record of

dispersal of the Barn Owl is also comparable to that of Falco peregrinus

and Butorides striatus, currently treated as polytypic species

(in addition to Alvaro’s examples). As

shown for the Furnariidae by Claramunt et al. (2012: https://royalsocietypublishing.org/doi/full/10.1098/rspb.2011.1922), high dispersal

ability actually impedes speciation.

“Personally, I will continue to vote NO

not because I have any pre-conceived notions of how many species are within T.

alba sensu lato – in fact, the tidbits of evidence cited herein by Nacho,

Tom, and Alvaro suggest current species-level taxonomy is incorrect -- but

because the evidence presented in the proposal is insufficient and because the critical

new evidence presented in the comments, although suggestive, is a compilation

of anecdotes until assembled and synthesized in a coherent way.”

Comments

from Robbins:

“”As Van suggested, will hold off for now on voting on this proposal until a

new proposal is presented.”

Comments

from Pacheco:

“I am convinced from the extensive approach that the

treatment of Tyto alba into three species is the best way to reflect the

evolutionary history of the complex.”