Proposal (921) to South

American Classification Committee

Treat Trogon rufus

(Black-throated Trogon) as consisting of five species, including one newly

described

Effect

on SACC list: This proposal would treat our Trogon rufus

as consisting of five species, one of which is newly described.

Background: Our current Note reads as follows:

7c. Dickens et al. (2021) found evidence

that T. rufus should be treated as five separate species, including one

newly described: Trogon muriciensis of the Atlantic Forest patches of

northeastern Brazil; they recommended elevating the subspecies tenellus,

cupreicauda, and chrysochloros to species rank. SACC proposal badly

needed.

Trogon rufus (Black-throated

Trogon) is a polytypic species with one of the largest distributions of any

trogon, with taxa treated as (nine described) subspecies occurring in three disjunct

regions: (1) from Honduras to the Chocó of northwestern South America, (2)

Amazonia; and (3) the Atlantic Forest from Alagoas through Brazil to eastern

Paraguay and Misiones, Argentina. They

have all been treated as conspecific from Cory (1919; albeit as T. curucui

due to early name confusion), Pinto (1937), and Peters (1945) through the

present.

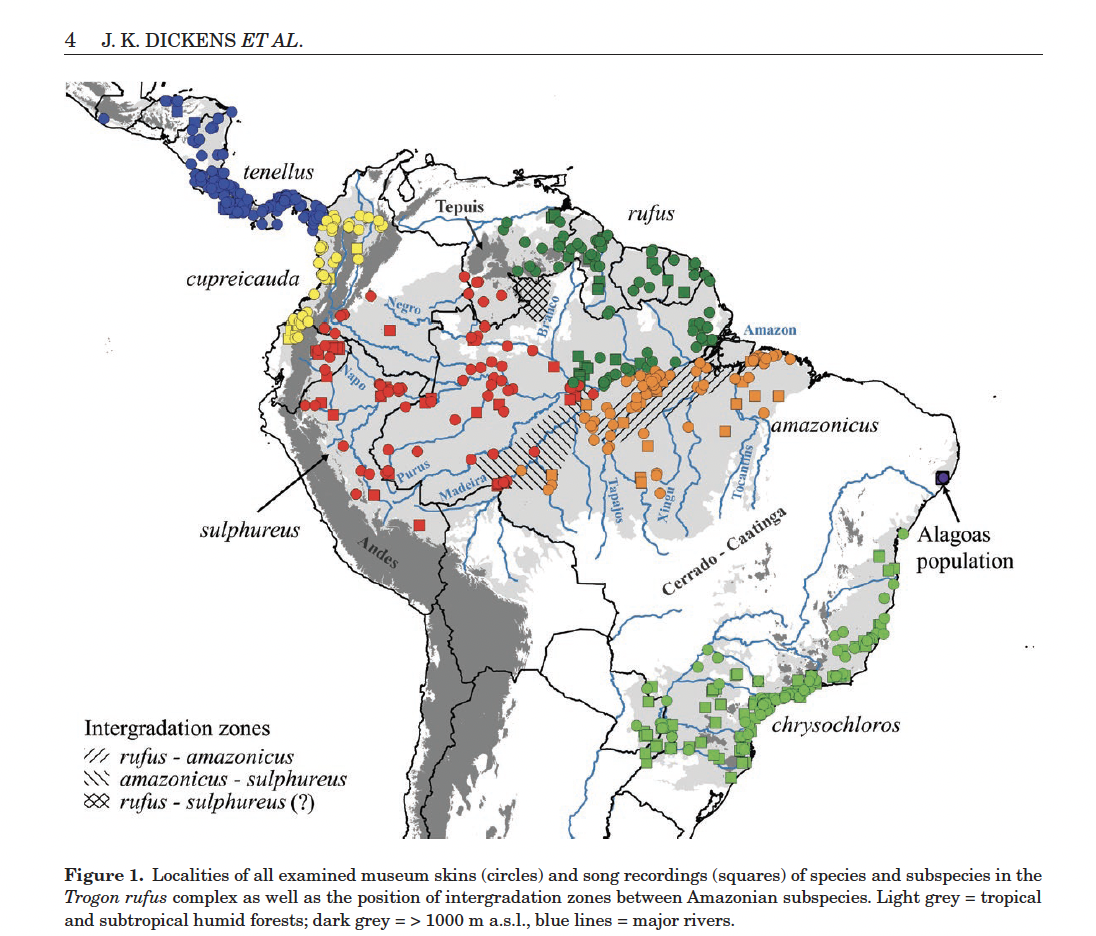

Here's

the map (from Dickens et al. 2021), which will be useful in evaluating the

proposal:

New

information:

Jeremy Kenneth Dickens and colleagues examined 906 specimens at 17 different

museums, including all taxa and all available type specimens, and gathered

spectrophotometric data, patterning, bare parts coloration, and standard

morphometric data on subsets of these specimens. They quantified vocal characters from 273

songs from throughout the distribution and including all named taxa. They also analyzed genetic samples (ND2 and

Cyt-b) from 29 specimens from throughout the distribution and all taxa. In other words, Dickens, Britton, Bravo, and

Silveira conducted an amazing study in terms of sample size, geographic

coverage, and critical data. Although

the genetic sampling included only mtDNA, I don’t think data from additional

genes would have made a difference in terms of determining species limits. The analyses are really excellent, and I

encourage everyone to check out the great graphics (my favorite is Fig. 3a on

male uppertail covert hue, although the color illustrations by Eduardo Brettas of

the taxa and their critical features is tough to beat). If only we had papers of this quality and

depth, from sophisticated analyses to classical taxonomy. The only weakness, given the vocal

differences, is the absence of playback trials, although to do that properly

would require fieldwork in multiple regions in the Neotropics.

A

detailed synopsis of all these data would take up a lot of space here. Check out the details for yourselves, but

here’s what stands out to me: the voices of all their proposed species are

qualitatively and quantitatively different; in contrast, no such major

differences are found among the Amazonian taxa that they recommend be treated

as subspecies of T. rufus sensu stricto.

For three of their proposed species-level taxa, 100% of the recordings

were correctly classified to species using linear discriminant analysis for

three of their proposed species-level taxa (chrysochloros, cupreicauda,

tenellus).

As

for the genetic data (ND2 1041 bp, cytb1011 bp), the results show prefect

congruence between geographic samples and relationships, and genetic distances

within geographic clusters and within taxa are small. The cis-Andean taxa are all weakly

differentiated, with time calibrations suggesting divergence times among

species at ca. 3-4 million years. The

big break is between cis-Andean and trans-Andean taxa, with a divergence time

estimated at ca. 5 million years ago.

The single sample of cupreicauda is fairly divergent from the 9

samples of tenellus.

(There

are lots of little nuggets within this 42 page paper that I could itemize, but

I will stop at just one because it has direct relevance to species limits. Atlantic forest chrysochloros is

almost exclusively insectivorous, in contrast to the other omnivorous taxa, and

it has a more heavily serrated bill for grasping large arthropods; they are

also known to be regular followers of monkeys, army ants, and coatis, evidently

more so than other trogons, so this all fits.

Actually, I can’t resist adding a second one because as the authors

note, it is important to keep in mind when assessing plumage in trogons: they

found evidence that there may be an environmental influence on iridescence,

which changes with elevation in chrysochloros.)

A

summary of their recommended species classification is as follows. See the paper for detailed diagnosis of each,

including coloration, pattern, eyering color, and song features. These sections also contain detailed

descriptions of each taxon, detailed synonymies, and useful notes on type

specimens

• Trogon tenellus Cabanis, 1862: Central

America to extreme NW Colombia (dpto. Chocó)

• Trogon cupreicauda (Chapman, 1914: N

Colombia south on Pacific slope to NW Ecuador

• Trogon rufus Gmelin, 1788 (including

nominate rufus of Guianan Shield, T. r. sulphureus of western

Amazonia, and T. r. amazonicus of eastern Amazonia)

•

Trogon muriciensis sp.

nov.: Alagoas Forest region; known only from type locality at Estação Ecologica de Murici.

• Trogon chrysochloros Pelzeln, 1856: Atlantic

Forest region

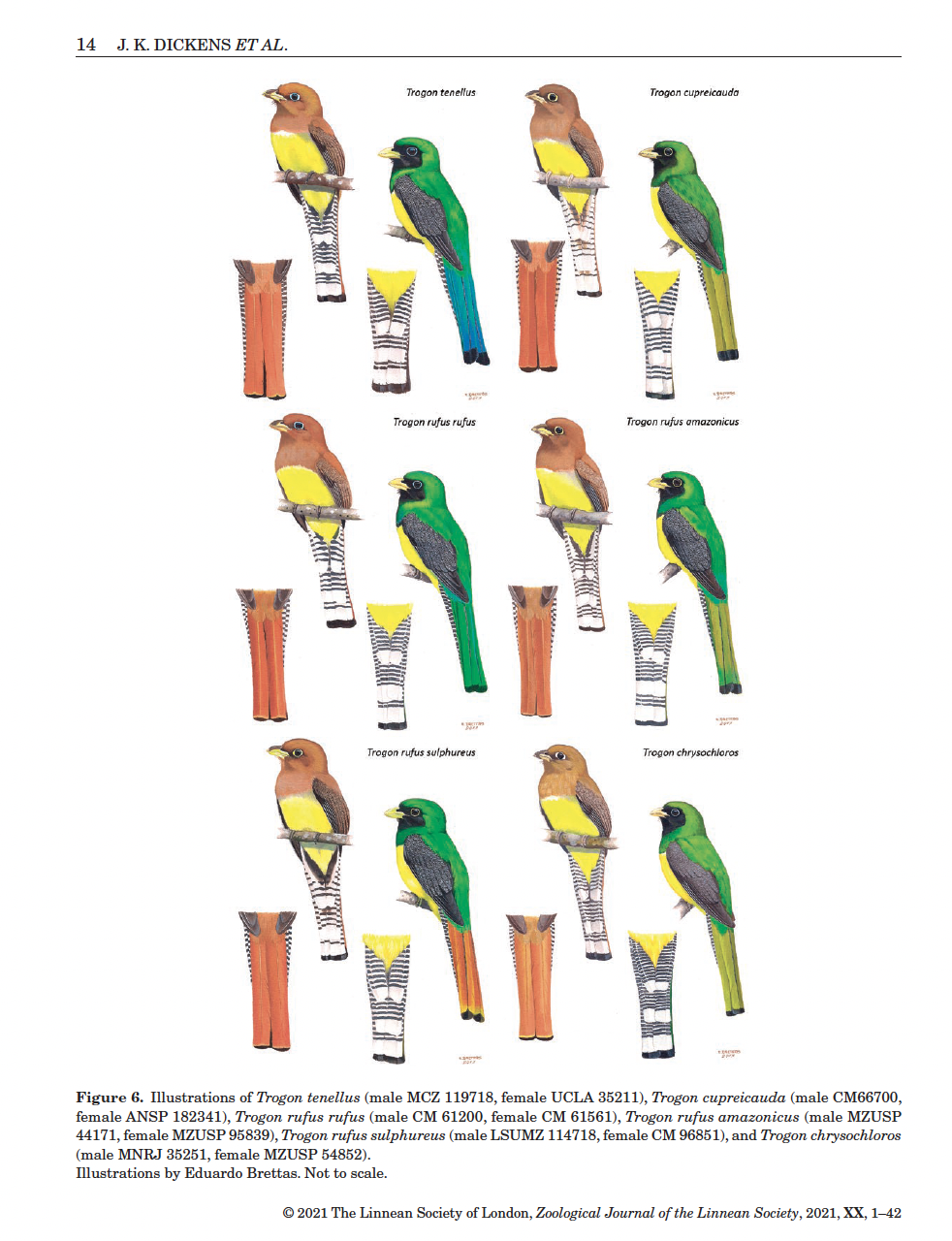

Here is a screen shot of the outstanding color

plate by Eduardo Brettas that illustrates the taxa:

The quality of evidence for species rank varies

among the 4 newly recognized or new species, so I think we should subdivide the

proposal as follows below. I suggest

listening to the recordings of the various taxa on xeno-canto: https://www.xeno-canto.org/explore?query=trogon+rufus&pg=1

A.

Treat tenellus as a separate species from T. rufus

Because

tenellus is entirely trans-Andean, it is not parapatric with any

subspecies of T. rufus, and thus the decision on taxon rank must rely on

comparative methods. The vocal

differences from other taxa are given as follows:

“Song: Diagnosed from neighbouring T.

cupreicauda by fewer notes per phrase, longer note durations and generally

higher note frequencies, particularly the introductory note high frequency.

Note frequencies, particularly the introductory note high frequency, are higher

than for T. rufus subspecies. Fewer notes per phrase, slower pace and

longer durations of notes and pause following introductory note than T.

chrysochloros.”

In

terms of phenotype, It has a breast band, unlike T. r. sulphureus or T.

r. amazonicus, from which it differs in several other less conspicuous

details (p. 26, and see the color plate (Fig. 6, p. 14, and above). The Diagnosis states that its pale (blue-gray

to white) eyering that distinguishes is from everything else, including

parapatric cupreicauda, but chrysochloros also is listed as

having the same color eyering.

B.

Treat cupreicauda as a separate species from. T. tenellus

This

is the other trans-Andean taxon, and it is sister to tenellus as one

would predict on biogeographic grounds.

If someone does not endorse tenellus as separate from the rufus

group, then also endorsing cupreicauda as a separate species from either of those

would be unlikely and would require special explanations. The vocal differences from other taxa are

given as follows:

“Song: Compared to T. tenellus,

the song has more notes per phrase, shorter note durations and generally lower

note frequencies. It also has more notes per phrase, shorter note durations but

a longer pause after introductory note, and generally higher note frequencies,

especially for the introductory note, than in T. rufus subspecies.

Compared to T. chrysochloros, the song has a slower pace, longer pause

following the introductory note, generally longer note durations and generally

lower note frequencies.”

In

their Factor Analysis (Fig. 4A), cupreicauda shows no overlap with the

other taxa on the axis heavily weighted by pace (slow) and note length (short).

In

terms of phenotype, the most striking feature to me is that the tail color is

closer to distant chrysochloros than to any other taxon, and in fact, it

differs the most in this feature from parapatric tenellus. The yellow eyering distinguishes it from all

other taxa. See p. 28 for a listing and

discussion of other color differences.

C.

Recognize T. muriciensis as a species.

As

rightfully emphasized by Dickens et al., little comparative material was available:

“Diagnosis: We had

little material available for the diagnosis of the new species Trogon

muriciensis, particularly regarding external morphology, so caution must be

taken until more information is collected. For comparison of plumage coloration

and barred patterning, only the holotype was available. For morphometric

traits, in addition to the holotype, we had measurements from the paratype and

a ringed individual. For other discrete traits, we had photos from online

depositories, in addition to those of the holotype (Supporting Information, Fig. S8) and ringed individual. For the song, we had slightly

more material, with recordings from five separate individuals (including the

holotype).”

The

vocal differences from other taxa are given as follows:

“Song: Compared to T.

chrysochloros, the song of T. muriciensis has fewer notes per

phrase, slower pace, longer note durations, longer pause following introductory

note and generally lower note frequencies. It is similar to T. r. rufus

but with generally more notes per phrase, higher introductory note frequencies

and higher loudsong note low frequencies. Compared to T. r. sulphureus,

it has wider bandwidth frequencies and generally more notes per phrase, whilst

against T. r. amazonicus, it has faster pace, shorter note durations and

a higher frequency introductory note. In relation to T. tenellus, it has

a greater number of notes per phrase, shorter pause after the introductory note

a generally lower introductory note high frequency, and generally lower peak

and high loudsong note frequencies. It differs from T. cupreicauda

by having fewer notes per phrase, longer note durations but a shorter pause

after the introductory note. The bandwidth frequencies of the introductory and

loudsong notes are generally wider than all other taxa, except T.

chrysochloros.”

In

terms of phenotype (with their caveats concerning N), there is no single

diagnostic character than I can see, but rather a combination of differences

not shared with any other taxon. See p.

30 for an enumeration of the ways it differs from adjacent chrysochloros

and members of the nominate group.

Genetically (Fig. 5), the single sample is sister to all 9 samples of chrysochloros;

however, all nine are distant, i.e. from São Paulo south (no samples from

closer Bahia to RJ), so that result would be expected on the basis of isolation

by distance alone.

D.

Treat chrysochloros as a separate species from T. rufus

The

vocal differences from other taxa are given as follows:

“Song: More notes per phrase, faster pace, shorter note durations

and pause following introductory note, as well as higher note frequencies and

wider introductory note bandwidth than T. rufus subspecies. The greater number

of notes per phrase, faster pace and shorter durations are also diagnostic

against T. tenellus. Compared to T. cupreicauda, the pace is

faster, the pause duration shorter and frequencies usually higher.”

In

their Factor Analyses (Fig. 4A, B [beware that B is mis-labeled as

Trans-Andean]), chrysochloros shows no overlap with the other taxa on

the axes heavily weighted by pace, pauses between notes, and number of notes.

As

for phenotype, this taxon has a relatively smaller bill that is more highly

serrated than any other taxon. The

density of barring on the wing panel and undertail coverts is diagnosably higher

than for any other taxon. The Diagnosis

says that it can be diagnosed from all other taxa (except evidently muriciensis)

by its blue-gray to white eyering, but I think this is an error – see tenellus. See p. 25 and the plates for additional

differences.

Discussion:

There

is no doubt that all taxa are diagnosable at some phenotypic level. But at what rank? Dickens et al. noted introgression at the

phenotypic level between T. r. rufus and T. r. amazonicus, T.

r. amazonicus and T. r. sulphureus, and T. r. rufus and T.

r. sulphureus; thus, they treated them as subspecies of the same species,

which is the logical treatment. Contact

zones are valuable test cases. Those

three contact zones provide a defensible standard for seeing which phenotypic

characters matter and which ones don’t in terms of barriers to gene flow. In the vocal analyses, these three taxa

mostly overlap in every feature analyzed, so song, as we have known empirically

for 70+ years, matters. The characters

that do not seem to matter in terms of barriers to gene flow, at least in this

group of trogons, are tail color (which varies dramatically among the three),

presence of subterminal tail band, presence of breast band (no surprise here,

because there is intraspecific variation in this in other trogons), width of

undertail barring, eye-ring color (ranges from blue to yellow even within amazonicus)

and any mensural characters. In other

words, almost every plumage and morphological characters they measured is irrelevant

as a barrier to gene flow, and so an important message of this paper is that

all these characters may be irrelevant when considering species limits in

trogons. (And I wish they had measured

the implications of this for the highly flawed Tobias-BLI 7 point scoring

scheme in terms of taxon ranking, but this would have added a tangent that

would likely have increased the paper length by a page.)

The

only other known contact zone is the one between tenellus and cupreicauda

at the Panama-Colombia border, where there are no documented cases of

introgression. Therefore, with the usual

caveats, I think we can take the differences between tenellus and cupreicauda

as potential isolating mechanisms, at least if they differ from those between

taxa in the T. rufus group. These

“if/then” comparative extrapolations come with obvious solutions, but in the

absence of alternatives, at least provide defensible rationale for

extrapolation to allopatric taxa in terms of assessing potential barriers to

gene flow, for better or worse. However,

none of the phenotypic characters other than voice show any difference from

those shown by Dickens et al. to not be potential isolating mechanisms in the T.

rufus group.

That

leaves vocalizations as the best proxy for estimating gene flow or lack of it.

I

personally am not the person to assess what the vocal differences mean in a

trogon framework -- -way too rusty. Are

the reported differences comparable to species level differences in other

trogon groups? I will leave that up to

those of you who have extensive recent comparative experience with trogon

voices. To me, when I listen to the

recordings, all I hear are the features in common, which to me are considerable;

but then again, many for-sure trogon species sound moderately similar. Is the absence of playback trials crippling

given what I perceive as subtle differences?

Ridgely & Greenfield (ergo also Mark Robbins) in the taxonomy volume

of Birds of Ecuador were consistently alert to vocal differences between bird

taxa west and east of the Andes in that country; however, they considered the

differences between voices cupreicauda and sulphureus to be only

“slight”, which is slightly worrisome to me. So, I look forward to your

comments.

A.

Treat tenellus as a separate species from T. rufus. I hesitate to make a recommendation on this one

other than noting my subjective feeling that I trust the authors of this paper on

this one because of the depth to which they have gone in these analyses. Certainly, tenellus occupies a nearly

unique multivariate space in the Factor Analysis of plumage characters in both

sexes (Fig. 2), more distinctive than any other taxon other than chrysochloros. However, in terms of vocal characters, tenellus

overlaps nearly completely with the T. rufus group despite differing in

average ways from them.

B.

Treat cupreicauda as a separate species from. T. tenellus. Because there is no phenotypic evidence of

gene flow between presumably parapatric cupreicauda and tenellus, I

regard this alone as a sufficient criterion for species rank between those two.

See the Discussion on p. 32 --- the authors were keenly aware of the

significance of this. With cupreicauda

vocalizations not overlapping with those of the other taxa in multivariate

space, we have additional indirect evidence for species rank. I’m also impressed with the phenotypic

differences between cupreicauda and tenellus, which are arguably

greater than between any two adjacent taxa.

The genetic distance between the two appears at least as larger as that

between any two adjacent taxa in the tree; however, there were no genetic

samples from Colombia, much less NW Colombia, closer to the contact zone than

the sample of cupreicauda from Provincia Esmeraldas, and perhaps sampling

within that ca. 700 km gap might produce a different result.

C.

Recognize T. muriciensis as a species. With a tiny N and no truly diagnostic

characters known, this one unfortunately represents the weakest case for

species rank, as the authors noted.

D.

Treat chrysochloros as a separate species from T. rufus. With its distinctive

plumage characters and vocalizations, the evidence for this split is strong in

my opinion.

Recommendations:

A.

Treat tenellus as a separate species from T. rufus. I’m ambivalent on this one, which is awkward,

because the evidence is nearly mandatory for treating its sister taxon cupreicauda

as a separate species, which would make Trogon rufus a paraphyletic

taxon if tenellus were included in T. rufus but not cupreicauda. On the other hand, at the population-species

level I don’t think monophyly, especially when only two labile mtDNA loci were

sampled, is a valid requirement for species rank (as I have argued several

times previously). With every passing

month, it seems that new data reveal ancient hybridization among species that

would make perilous the use of any single gene tree as representing the “true”

history.

B.

Treat cupreicauda as a separate species from T. tenellus. YES. I

think these have to be treated as separate species given the parapatry with no sign

of introgression.

C.

Recognize T. muriciensis as a species.

Ambivalent. The endangered status

of this one should not, in my opinion, influence the taxonomic decision;

otherwise, this undermines the credibility of the scientific process. Certainly this should be recognized as a

separate subspecies, minimally, and I look forward to others’ comments on this.

D.

Treat chrysochloros as a separate species from T. rufus. YES on this one for reasons given above.

E.

English names: Dickens et al. proposed the following:

• Trogon tenellus = Graceful

Black-throated Trogon

• Trogon cupreicauda = Kerr’s

Black-throated Trogon

• Trogon rufus = Amazonian

Black-throated Trogon

•

Trogon muriciensis = Alagoas

Black-throated Trogon

•

Trogon chrysochloros = Southern Black-throated Trogon

• Trogon chrysoc

A

lot of you don’t like long compound names.

In fact, Tom’s blood pressure just skyrocketed when he read this. I understand that view, but in this case I

like the compound names because: (1) it keeps intact the link to Black-throated

Trogon, thus making it clear within a long list of trogon names which species

are members of the T. rufus

superspecies; (2) maintaining Black-throated in the name retains a somewhat

useful character in separating them from other trogons within their range (I

think); (3) they are marginally distinguishable anyway by plumage; and (4) if

one drops the “Black-throated”, then we would probably have to invent new names

for two of the species because “Southern Trogon” and “Amazonian Trogon” are

misleading names from the perspective of the genus as a whole. Southern Black-throated Trogon, as noted by

Dickens et al., resurrects a historical name, thus providing continuity with

older literature.

Also,

“Graceful” is somewhat unsatisfactory for tenellus (Latin for

“delicate”, fide Jobling), with or without Black-throated, although as

noted by Dickens et al., it resurrects the historical name used in Middle

American bird literature from at least Ridgway (1911) on, until Eisenmann

(1955) changed it to Black-throated after its lump (Peters 1945) into T.

rufus. Some people don’t care about

historical continuity, but for researchers, it is helpful, e.g. “Graceful

Trogon” brings up 597 hits on Google, including Gould’s monograph on trogons,

and 13 hits in Google Scholar.

“Kerr’s”

is an eponym, which will anger the anti-eponymous zealots; however, Kerr was a

female collector, which was highly unusual for the era (1912!), an American

living in Colombia and collecting birds, and she collected the type specimen. In

my opinion, not only deserves the honor but also calls attention to her

generally overlooked contributions. See

the attached provided through

Gustavo Bravo, admirably dug out by Andrés Cuervo. (You may have lost your chance to buy

Ingram’s Milkweed Cream, unfortunately).

At

this point, for English names, let’s keep it simple: A YES means acceptance of the proposed names,

at least for those we end up recognizing, and a NO means something else, either

no compound names or modifications of the modifiers or both.

[Revision

15 June 22: To really keep things simple, let’s go Y/N on compound names vs.

simple names for now, and worry about modifiers later]

References:

DICKENS, J. K., P.-P. BRITTON, G. A. BRAVO, AND L.

F. SILVEIRA. 2021. Species limits, patterns of secondary contact

and a new species in the Trogon rufus complex (Aves:

Trogonidae). Zoological Journal Linnean

Society: 1–42.

Van

Remsen, September 2021

Comments from Areta:

“A. YES. Plumage and genetics support this

split. See comments on C regarding vocalizations.

“B.

YES. Mostly based on the apparently distinctive vocalizations (despite

methodological shortcomings), marked change in tail hue over a short distance

near the zone of geographic proximity between them and less so based on the

phylogenetic information (the single sample of cupreicauda is quite away from the southern limit of tenellus).

“C.

NO to recognizing muriciensis as a

separate species. The data is very limited and unsatisfactory to make this

move. The shallow genetic divergence, lack of diagnostic plumage features, and

similar vocalizations to chrysochloros

indicate to me, at most, subspecific status. Regarding the vocalizations, I

have trouble in seeing the most basic parameters of the spectrograms in Figure

4 (e.g., time and frequency values), but these seem to have been built using

different scales, thereby presumably distorting the similarities and

differences among vocalizations. It also seems to me that there are important

vocal differences among sexes in Trogons

(fleetingly disregarded by the authors) that were not taken into account when

making the comparisons; this can easily be heard and seen in spectrograms when

couples of birds duet or respond to each other. I have trouble in matching the

presumably "typical" songs depicted in the spectrograms to results of

the discriminant analyses: songs which look very different overlap widely,

suggesting that measurements were not able to capture key features of the

sounds or that the spectrograms are not so typical. Finally, several recordings

of chrysochloros sound exactly like muriciensis.

“D.

YES to splitting chrysochloros from rufus. Plumage, vocal and genetic data

agree in this split.”

Comments

from Donsker:

“E. My formal vote is NO. I think that we can come up

with better English names than those proposed.”

Comments from Bonaccorso:

“A. YES, but it makes more sense to accept 921B.

“B. YES. T. tenellus and T. cupreicauda seem to

have reached enough phenotypic differentiation (especially tail color; I love

the tail-hue figure!) and vocal differences. However, I am not impressed by

their genetic differences because the range of the species along Colombia was

not covered in the phylogenetic analysis, thus, differences could result from

isolation by distance. However, the possibility of parapatry and lack of

intermediate individuals supports the potential lack of gene flow.

“C. “YES, but a bit hesitantly (I agree with Nacho that the data

are sparse). Phenotypically, the Alagoas population is not so different from chrysochloros.

However, vocally (and I am no expert), it seems to be very different. Still,

the low sample size (N = 5) may not reveal the variation spectrum of

vocalizations in the Alagoas population. Genetic differentiation is weak and

based on one sample, whereas genetic sampling of chrysochloros does not

cover localities closest to the Alagoas population. In short, I think the

decision should be based on the acoustic data if some of you (experts on the

subject) think the level of differentiation merits species status.

“I disagree with the position that no special considerations

need to be made when the decision is about endangered species. I think there

has to be asymmetry when considering species that may or may not be endangered.

If, in the end, they are no good species, some money and effort may be lost,

but at least the habitat of the species may get some level of protection for a

while (which, needless to say, will benefit many other species). It is much

worse to err in the other way. Not recognizing an endangered species and waiting

for more data may have much worse consequences, especially in cases like this,

where the range seems tiny. Also, from my experience with the Blue-throated Hillstar,

the fact that we recognize new, endangered species does not guarantee immediate

incorporation into IUCN lists (even after repeated requests to BirdLife

International). Meanwhile, deforestation continues, and funds are not available

for research, research-based conservation, or protection. So, our delay in

recognizing these species may have fatal consequences under the current

circumstances.”

“D. YES. In this case, vocal and genetic evidence seems to

support species status. I don´t think phenotypic differentiation is so strong

or useful in defining species status in this case. T. sulphureus seems

very different from rufus and still, they hybridize.”

Comments

from Pacheco:

“A, B and D. YES. Plumage, genetics, and vocal

repertoire provide a good endorsement for treating these taxa at the species

rank.

“C. A vacillating YES, for the exact reasons explained by Elisa.

Obtaining more data (vocalizations, genetics) and conservation measures for

this population becomes dramatic races against the clock.”

Comments

from Stiles:

“YES to all except C.”

Comments

from Josh Beck on Part E (voting for Claramunt on English names): “I have witnessed a lot of mild confusion among both friends

and strangers in terms of which Trogon species carries which name, as so many

of the names could readily apply to multiple species. I also at times have to

stop and think for a second which of the white-tailed Trogons is called

White-tailed, which of the green-backed is called Green-backed, and which of

the Amazonian Trogons is called Amazonian. Across all this, despite vocal

differences between the potential daughter species, Black-throated is a name

that no one confuses as it corresponds to one of the more visually and vocally

distinct Trogons (seas currently defined). For this reason, despite the

proposed compound names being awkward, I am highly in favor of retaining

Black-throated in the name. Coining 5 novel names in a group of birds that all

look very similar might make for more elegant titles in field guides but will

not serve birders or other English name users, and I really think that “will

these names best serve common name users” needs to be a driving principle. As

far as the modifiers, I feel that Graceful is not very helpful as it provides

zero identification / location information. I would suggest Central American or

Middle American is an obvious possibility that is far more useful. As for

Kerr’s, as deserving as Kerr may or may not be, and independent of one’s views

of patronyms, the name provides no information or help locating or identifying

the species. Choco seems, at first glance, the obvious choice for a far more

useful name. This situation is analogous, to me, to the names for the

Daggerbills. Within the two, fortunately one of them bears a useful geographic

modifier so it is easy to keep them straight, as Geoffroy’s doesn’t really tell

the average birder or English speaker anything. If they hypothetically were

named Graceful Daggerbill and Geoffroy’s Daggerbill there would be a lot of

people, myself included, frequently pausing for a moment to remember which one

is which.”

Comments

from Jaramillo:

“YES to A, B, C, D. I guess it would be good to give a set of opinions

and viewpoints, but they have all been made by others so far. I do think I am

giving benefit of the doubt to the researchers who put this together in

painstaking detail, and have provided us a framework. In a sense, I do not feel

qualified to counter their arguments on these opinions.

“E

– NO. The compound names do not do much here that is beneficial in my mind. If

we are to have a compound name, it would be better for it to be “yellow-bellied

trogon” to separate from the red-bellied species, I am not serious, but in the

end that would be more useful to English speakers. At this point, with such a

massive split, the name “Black-throated Trogon” seems to be destined to be

forgotten and in this case, likely that is a good thing given that none of

these forms are best served by that name?”

Comments

from Lane:

“A. YES.

“B. YES.

“C. No. The

characters distinguishing its voice from T. chrysochloros seem weak, and

weakened even more by the recording on X-c recorded in 2021 <https://xeno-canto.org/628115> that

has a song with more notes. I just don't think this taxon will have significant

defining characters once it is given more scrutiny.

“D. YES.

“E. NO. I

am not all that in favor the "XXX Black-throated Trogon" because I am

not usually very impressed by compounded names of this nature, particularly

when there are so many syllables involved (kind of a "Black-backed

Three-toed Woodpecker" sort of situation in my mind).

"Black-throated" is not at all a defining character for any member of

the complex, so it is a name I'm happy to lay aside in preference for something

like "Graceful Trogon" (T. tenellus), "Kerr's

Trogon" (T. cupreicauda), "Sulphur-bellied Trogon" (T.

rufus and related taxa), and "Saffron-bellied Trogon" (T.

chrysochloros incl. muriciensis)... or something along those lines.”

Comments

from Nigel Collar (voting for Bonaccorso on English names):

“E.

YES for compound names, although I’d go for:

Northern Black-throated Trogon T.

tenellus

Western Black-throated Trogon T.

cupreicauda

Central Black-throated Trogon T.

rufus

Eastern Black-throated Trogon T.

muriciensis

Southern Black-throated Trogon T.

chrysochloros

“Reasons: Just keeping to the points of the compass (plus

Central—admittedly the hardest to stomach) homogenizes everything and makes it

seem much fairer (more equal) and simpler; they all get two extra syllables

with the emphasis on the first—slips off the tongue. It doesn’t matter to me

that the Northern is more western that Western. Everyone’ll get used to it

quick enough.

“(Personally I don’t buy muriciensis as a species, and I’d

treat it in Southern. (You could almost dare to call Central “Eastern” in that

case, but let’s not go there…)”

Additional

comments from Josh Beck (voting for Claramunt on English names):

E.

[YES for compound names].”I've mulled this over quite

a bit and asked around a wide range of Neotropical birders and guides for their

opinions, so this is my vote but based heavily on the opinions of a range of

American (US), South American, and European birders and guides. I do think that

Dan and Alvaro make good points about the lack of uniqueness or elegance of the

compound names. I also dislike them. Really, there are almost no good names in

the Trogons. But new novel names coined will be equally useless and have

no history, further disrupting stability and losing the affinity of these 4-5

species. The daughter species here are a phylogenetic group and

"black-throated" is one of the better understood/better known names

among a sea of not terribly informative nor memorable Trogon names. Removing

the black-throated part would be acceptable if new, useful, elegant, uniquely

identifying names were available, but barring divine inspiration, any and all

names for these birds are going to fail to be uniquely identifying or inspiring

or memorable. For that reason, I really think, and all but one of the people I

asked agreed, that despite the ugliness and awkwardness, it's far more useful

to retain the black-throated descriptor. For what it is worth, most people I

asked also thought that the modifiers to "Black-throated Trogon"

should be geographically based as anything else is, again, not really helpful

in distinguishing the daughter species nor remembering the names.”

Comments from Remsen: YES to all except C, for which

the evidence for species rank is weak, as noted in the proposal and several

comments. As for E (compound names), I

find Josh’s comments persuasive. If

someone had come up with a compelling set of one-word “first names”, then that

would be one thing, but in the absence of this, I think the compound names are

more useful in that they help sort out a bunch of generally poor trogon names

by branding one species complex with a name that provides historical

continuity.”

Comments from Whitney (voting for Robbins/Schulenberg on E):

“E. I favor retaining “black-throated” as part of the English

names. My name is Bret, and (mostly in

Latin America) I am occasionally asked if it’s a nickname, or, what Bret means.

Heck, I have no idea, so I tell them,

“It’s meaningless, but my mom gave it to me, and it’s stuck.” I expect this is exactly what would happen

with any of the names proposed by Dickens et al. I think the names they proposed are fine. “Graceful” may leave some wringing their

hands, but heck again, it doesn't matter, because it will serve the intended

purpose of labeling a geographically defined entity (an entity that has borne

that name in the past). Now, if we

remove “black-throated” from the names, we do, in fact, lose valuable

information, as the "black-throated trogon” (T. rufus complex) everywhere

is distinguished from all other (especially sympatric) trogons in being a

lowland, terra firme understory (~3-9 m), yellow-bellied, barred-tailed,

eyering-lacking, largely insectivorous Trogon (you notice I didn’t

mention “black-throated” because that feature is truly useless — but again,

that’s beside the point, it’s just a name, and a name that’s worked well

forever). It is useful to ornithologists

and birders to retain “black-throated” because it immediately categorizes these

birds across their wide geographic radiation, and it provides a logical (and

phylogenetically consistent) order among the multiple species of trogons

sharing the range.

“I think it’s important to recognize that compound naming was not

applied in the T. viridis split, which has led to confusion that would

have been avoided by retaining “white-tailed”. I think it would make sense to revisit those

names, and to apply compound names to future splits/descriptions of trogons

(and, imho, most other splits, such as was done with the Hypocnemis cantator

complex, which are now all “warbling-antbirds”… which, yes, don’t warble… but

no one really cares [I don’t think…]).

“As to the status of T. muriciensis, I would vote NO from a

purely scientific perspective, no emotion in the mix. I think there is a strong likelihood that

having an appropriate geographic sample of tissues from the northern end of the

range of chrysochloros would further close, but not erase, the

relatively minor genetic gap with the single sample from Alagoas. At this point, there are multiple species

restricted to the "Pernambuco Center of Endemism”, including a highly

distinctive curassow that has just recently been reintroduced there (project in

very early stages). These multiple

species and subspecies, and especially the forests where they occur, are

clearly “on the map” for Brazilian and international conservation priorities,

and I believe the Alagoas/Pernambuco region was the focus for conservation

funding raised at a recent Global Birdfair in the UK. Even if the region were not receiving much

global attention, I would not recommend species status for the Alagoas bird —

given its very close similarity to chrysochloros — without a more robust

analysis.”

Comments from Robbins: “Although the authors have gone

into extraordinary detail from a plumage, soft part, and vocal standpoint, the

genetic data are weak and in the case of proposal B, potentially suffer from

the lack of sampling. I would prefer to

have more genetic data before making a definitive recommendation; however, that

might not be forthcoming for some time. The

reason I put emphasis on that data set is that there are not consistent

differences in morphology and vocalizations across this complex. It should go

without saying that differences in plumage among most of these taxa are

relatively small, with male tenellus and rufus sulphureus

standing out in dorsal tail coloration. Moreover, much of those dorsal tail

differences are represented within the Amazonian populations, i.e., amazonicus,

nominate, and sulphureus. Thus,

if one treats Amazonian populations as a single species then dorsal tail

pattern becomes questionable as a species-defining character.

“A) NO, because of the above concerns with the genetic data

coupled with overlap between tenellus and the Amazonian group of rufus

in vocalizations. Also, see comments under B.

“B) NO, we need data where tenellus, at least

theoretically, comes into contact with cupreicauda at the

Panamanian/Colombian border. Note that

there is only a single genetic sample of cupreicauda, and it is from

Esmeraldas, far from the potential contact zone. That interface might shed

light on the importance of dorsal tail pattern (given the differences between

these two) and the importance of vocalizations. Depending on those data, I could see where tenellus/cupreicauda

are treated as a species and it is considered a separate species from

cis-Andean populations.

“C) NO, data are too limited to assess taxonomic status.

“D) NO, although given current data, I lean more towards

recognizing this as a species, primarily because of differences in

vocalizations as outlined in Fig. 4 in Dickens et al. and the disjunct

distribution. However, to be consistent with what I have outlined above I vote

No. Note that plumage and perhaps soft

part colors are not unique to chrysochloros, and the limited genetic

data indicate that it is close to Amazonian populations (no surprise).”

Comments from Zimmer:

“A. YES. Despite lack

of diagnostic vocal differences, I have a hard time accepting that there are

two conspecific taxa whose ranges are widely disjunct, and separated not only

by the Andes, but by the presence of another taxon in the same group (cupreicauda), that is demonstrably

different from both the trans-Andean taxon and the cis-Andean taxon, and that cupreicauda is parapatric with tenellus without evidence of

intergradation between the two.

“B.

YES. Although it is not listed as a

subset of this Proposal, it would also follow that I would also vote “YES” on

treating cupreicauda as a separate

species from rufus/amazonicus/sulphureus. As Van noted (in the Proposal),

phenotypic/plumage characters are all over the map in “Black-throated Trogon” (sensu lato), and even within some

subspecies groups (the Amazonian/Guiana rufus-group),

and really don’t seem to work as isolating mechanisms. Given that, to quote Van “That leaves

vocalizations as the best proxy for estimating gene flow or lack of it.” Accordingly, to my ears, songs of cupreicauda are distinct from those of tenellus to the north and west, and

those of the various Guianan/Amazonian cis-Andea forms to the east and

south. The absence of phenotypic

evidence of gene flow between these two parapatric populations is further

supporting evidence, which, admittedly, is weakened somewhat by the lack of

sampling from closer to the potential contact zone.”

“C.

NO, at least not for now. Sample sizes

are just too small in my opinion, particularly given the absence of data from chrysochloros from Bahia to Rio de

Janeiro, more proximate locales, which, when added to the mix, could well

narrow any apparent gaps regarding potential differences in vocalizations,

plumage, and genetics. I would note,

however, that from the vocal samples I’ve listened to, muriciensis is closer (at least in song characters) to Amazonian

populations than to fellow Atlantic Forest taxon chrysochloros. This would

certainly fit an established pattern of several Atlantic Forest taxa from the

Alagoas-Pernambuco center of endemism having their closest relatives

distributed in SE Amazonian rather than the S Atlantic Forest. For example, think Automolus lammi (closer vocally and genetically to A. paraensis than to A. leucophthalmus), or Thamnophilus aethiops distans, or Hemitriccus griseipectus naumburgae. There’s also the broader pattern of

widespread Amazonian taxa having highly isolated but closely related

populations in the northern part of Brazil’s Atlantic Forest (south through

Espírito Santo to N Rio de Janeiro for many of them) – think Cinereous

Antshrike, Cinereous Mourner, Ringed Woodpecker, Bright-rumped Attila, Thrush-like

Wren, White-winged Potoo, etc.

Obviously, there are other species-pairs where the close affinities are

between Pernambuco regional specialties and SE Atlantic Forest birds (Myrmotherula snowi/unicolor comes

rapidly to mind), but the point is, that there are numerous examples of taxa

from the forest fragments of Alagoas/Pernambuco being more closely related to

Amazonian counterparts than to any taxa from farther south in the Atlantic

Forest. So, it’s not implausible to me

that muriciensis could be distinct

from chrysochloros, but I do think we

need more data points to be confident that is the case.”

“D.

YES. This one is the most different

vocally (perhaps, along with cupreicauda)

from any of the others, and those vocal differences are congruent with

phenotypic distinctions (even if it turns out these aren’t important as

isolating mechanisms), ecological differences, genetic differences, and

established biogeographic patterns.”