Proposal (922) to South

American Classification Committee

Treat Turdus daguae as a

separate species from Turdus assimilis

Effect on SACC: This would treat the subspecies daguae, our

sole representative of otherwise Middle American Turdus assimilis as a

separate species. Note: this is a slightly modified version of

a proposal submitted to NACC.

Background: This taxon

is currently treated by NACC and SACC as a subspecies of Turdus assimilis, but as a

result of anecdotal comments, NACC and Dickinson & Christidis (2014)

treated it as a subspecies “group”.

Here’s the text from AOU (1998):

“Groups: T. assimilis

[White-throated Thrush] and T. daguae Berlepsch, 1897 [Dagua Thrush]. Turdus

assimilis and the South American T .albicollis Vieillot, 1818

[White-necked Thrush], constitute a superspecies (Sibley and Monroe 1990). Many authors (e.g., Wetmore 1957, Wetmore et

al. 1984, Ripley in Mayr and Paynter 1964) consider them conspecific but see

Monroe (1968) and Ridgely and Tudor (1989).”

I included the part

about albicollis to explain why some older literature treats daguae

under Middle American Turdus albicollis; also, albicollis becomes

part of the problem, as you’ll see below.

Here is our SACC Note

on this:

12a. The subspecies daguae of the

Chocó region has been treated as a subspecies of T. assimilis, and most

recent authors have treated them as conspecific (e.g., Hellmayr 1934, Ripley

1964, Meyer de Schauensee 1970, Ridgely & Tudor 1989, AOU 1983, 1998, Sibley

& Monroe 1990, Clement 2000, Dickinson & Christidis 2014). Ridgely & Greenfield (2001), however,

considered daguae to be a separate species, in part because its voice

resembles that of T. albicollis more than that of T. assimilis. Nuñez-Zapata et al. (2016) presented evidence

that daguae should be treated as a separate species from Turdus

assimilis. Del Hoyo & Collar

(2016) treated as a subspecies of T. albicollis, not T. assimilis,

based on Boesman’s (2016) assessment of songs. SACC proposal badly

needed.

History of taxonomic treatments: Berlepsch

described daguae as a species in Turdus in 1897 from lowland

western Colombia, with the Río Dagua as part of the type locality, which is

south of Buenaventura and NW of Cali (dpto. Cauca). Ridgway (1907) did not mention the taxon, so

I assume it was not recorded in Panama until sometime after 1907. However, Hellmayr (1911; PZSL), Bangs &

Barbour (1922; Bull. MCZ), and Chapman (1926: Birds of Ecuador) soon treated daguae

as a subspecies of Turdus assimilis (at that time known as Turdus tristis).

Hellmayr

(1934) treated it as a subspecies of T.

assimilis with the following

explicit rationale:

“Turdus assimilis daguae

Berlepsch: Differs from T. a. cnephosa [the adjacent subspecies in

central Panama] in smaller size, shorter bill, much darker (bister brown) upper

parts, and very much darker, nearly sepia brown color of the chest, sides, and

flanks. ….

“In coloration, this race

comes nearest to T. a. rubicundus, but is still much more intensely

colored. Although its much smaller dimensions and its shorter, entirely dusky

bill serve to distinguish it without difficulty, yet the close similarity to

the west Guatemalan form seems to afford sufficient evidence for its

association with the assimilis group, which, as suggested by Miller and

Griscom, may ultimately prove to be conspecific with albicollis.”

This treatment was followed by essentially all subsequent authors,

including Ripley in “Peters” (1964), Meyer de Schauensee (1966), and the AOU (1983),

which stated: “The populations of T. assimilis from eastern

Panama (eastern Darien) south to Ecuador are sometimes considered a distinct

species, T. daguae Berlepsch, 1897 [Dagua Robin].” I’m actually uncertain where this statement

“sometimes” came from because I can’t find a treatment from the 1900s on that

did treat it as a separate species. [Anecdote: the frustration that hundreds

of examples like this in AOU 1983 caused me to start lobbying when I joined the

Committee in 1984 for citations for all such statements in future AOU

Checklists; Burt Monroe, who wrote almost all those Notes in the 1983 Checklist

often could not remember the source of many of the statements].

Subsequently, Ridgely & Tudor (1989) treated daguae as a subspecies of T.

assimilis and mentioned only that it was not well known. Clement (2000; Thrushes; Princeton U. Press)

listed it as the southern subspecies of the 10 that he recognized for T.

assimilis; he described the plumage differences but did not illustrate it

separately.

Then, Ridgely &

Greenfield with the collaboration of Robbins and Coopmans (2001; The Birds of

Ecuador Vol. 1) treated daguae as a separate species (Dagua Thrush) from

T. assimilis, with the following text --- note that no actual data are

presented:

“Daguae has

usually been treated as a subspecies of T. assimilis …. Now that

more information is available regarding the voice of daguae – it is distinctly

different from that of T.

assimilis of Middle America – we consider it more appropriate to treat T. daguae as a separate

monotypic species, differing not only in voice but also in several

morphological features. Daguae’s

voice actually more closely resembles that of cis-Andean T. albicollis,

suggesting that daguae may be more closely related to that species.”

Collar in HBW (2005) not only

treated them as conspecific but also treated all of assimilis as

conspecific with South American T. albicollis. He mentioned that daguae had been

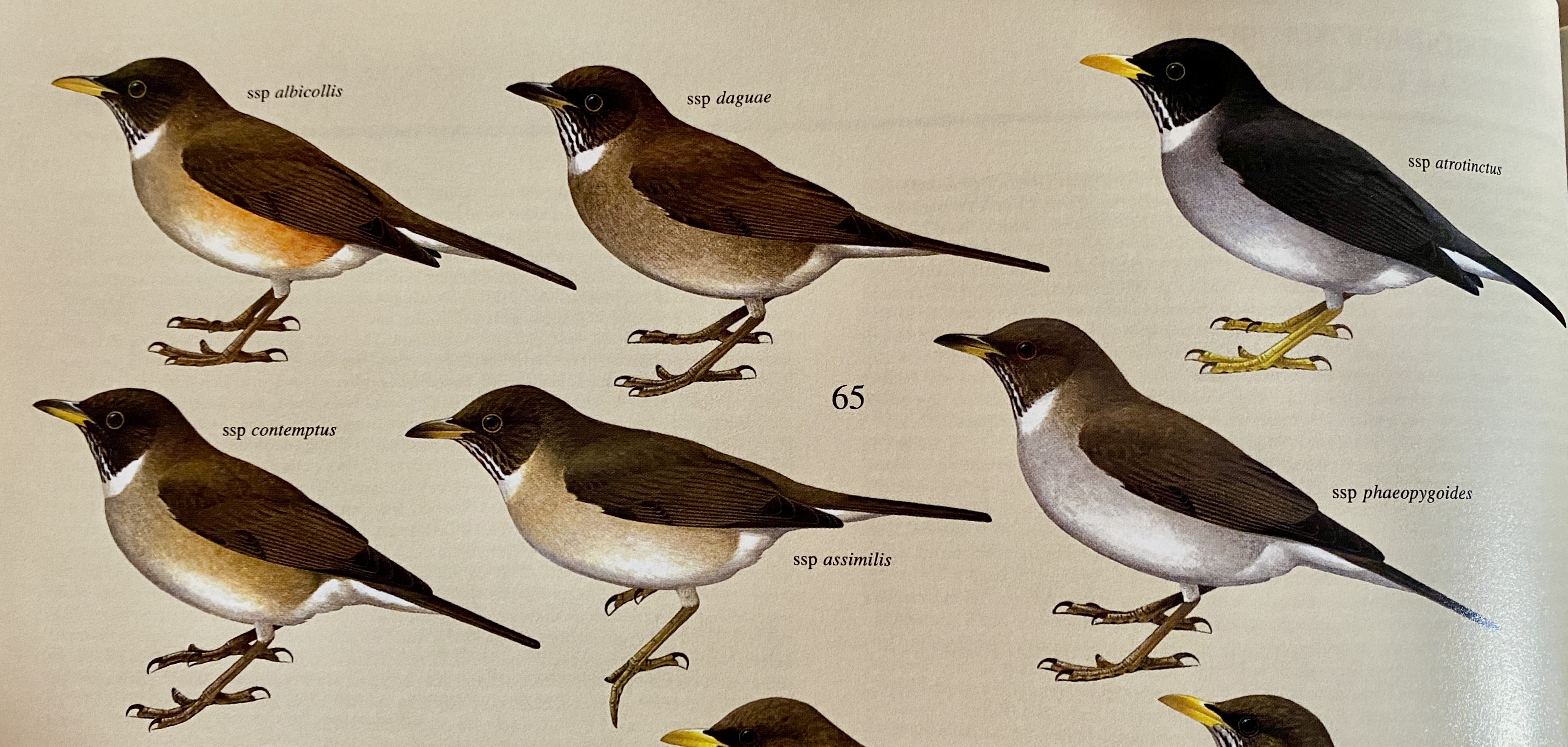

proposed as a separate species. Here is

the relevant section of the plate:

Dickinson & Christidis (2014) treated daguae as

conspecific with T. assimilis but placed daguae in its own

subspecies group, as per AOU (1998), and cited Ridgely & Greenfield for the

possible split. Angehr and Dean (2010;

The Birds of Panama. A Field Guide) treated them as conspecific; their range

maps nicely illustrate the substantial gap in their distributions in the

lowlands of central Panama

Del Hoyo & Collar (2016) treated daguae as conspecific

with …. drumroll … not T. assimilis but with cis-Andean T. albicollis. This was based on Boesman (2016), who

actually used the Collar (2005; HBW) species limits, i.e. broadly defined T.

albicollis, not the two species treatment in Del Hoyo & Collar

(2016). His analysis, however, shows

that T. assimilis is clearly different from T. albicollis in song

features, and that the song of daguae is actually difficult to

distinguish from the eastern group of T. albicollis subspecies. Although Boesman would be the first to tell

you that more in-depth analysis is needed, he does establish that if voice is a

reliable indicator, then daguae belongs with T. albicollis. Recall also that Ridgely & Greenfield

(2001) noted the similarity of daguae song to that of albicollis. That trans-Andean Chocó and cis-Andean

populations are sisters is a common biogeographic pattern in Neotropical birds.

Genetic data

As for genetic data, as argued in previous proposals,

I think they are of dubious value for determining taxon rank of allopatric

populations, although perhaps our best estimates of divergence times.

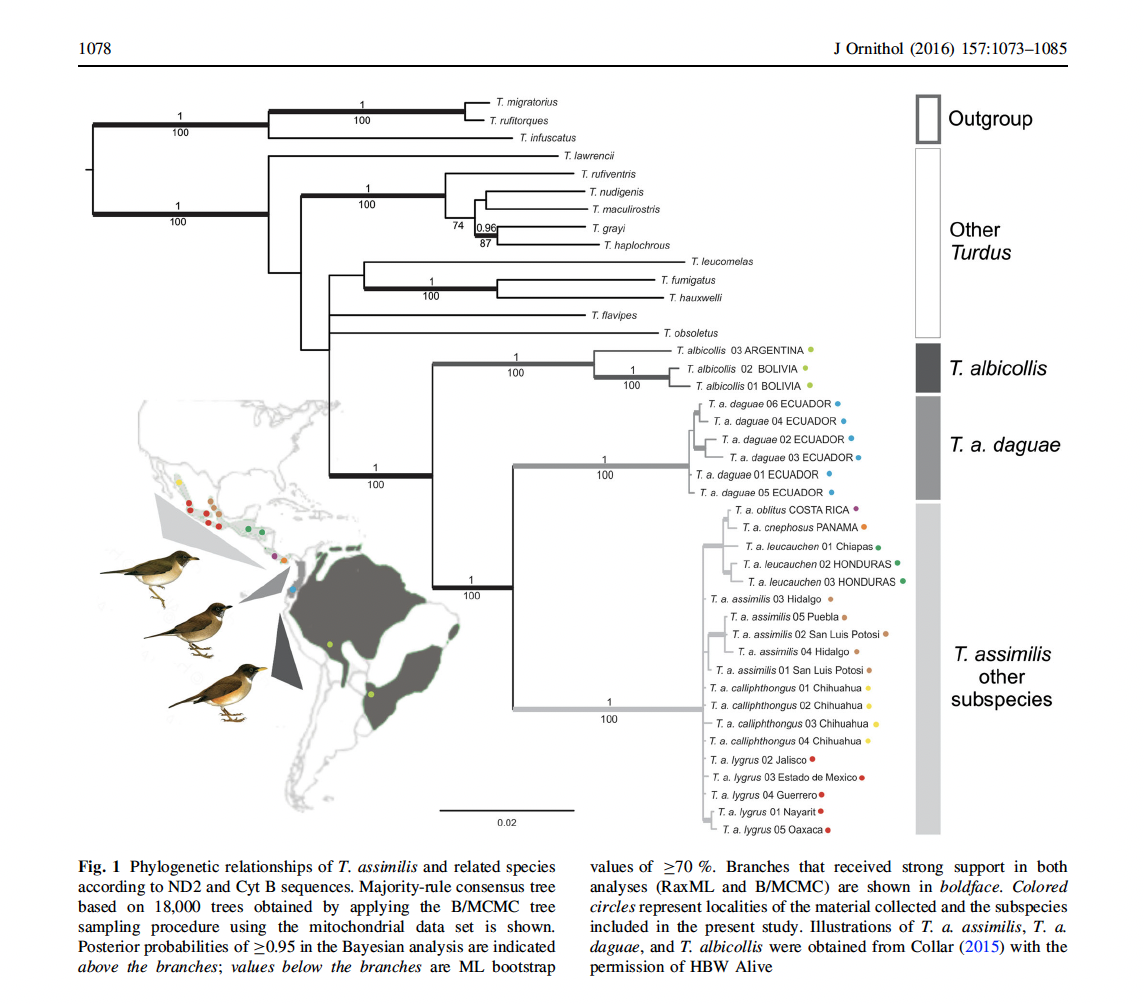

The only study that specifically addressed the daguae

issue was that of Núñez-Zapata et al. (2016), which focused on the T.

assimilis group. Using 2

mitochondrial genes (cyt-b, ND2) and 25 individuals, their tree shows that daguae

is strongly separated, with strong support, from the other subspecies and

populations of assimilis:

Of interest is that daguae is sister to assimilis,

not the albicollis group, which provides evidence against inclusion of daguae

in T. albicollis as in Del Hoyo and Collar (2016). However, this result could be a “gene

tree/species tree” or ILS problem given the limited gene sampling, and so

hopefully subsequent studies will include nuclear or genomic data. Meanwhile, this places burden-of-proof, in my

opinion on moving daguae to albicollis.

Núñez-Zapata et al. (2016) considered the genetic

data as indicating species rank for daguae based on genetic distance and

reciprocal monophyly. However, they

themselves noted the problems with using comparative genetic distances. Also, with N=6 daguae samples, all

from three localities in NW Ecuador near the southern extreme of its range, a

claim of reciprocal monophyly seems premature.

All such claims are one additional sample away from being refuted. (Would someone please write a paper on the

problems with “reciprocal monophyly” with respect to N and geographic sampling;

certainly, some minimum number of specimens would seem required to make such a

claim, depending on genes sampled, as well as some consideration of the

geography of sampling given that the probability of detecting shared alleles should

decrease to some degree with distance from the former contact zone.)

Batista et al. (2020) used UCEs in their

broad study of Turdus but unfortunately did not include daguae.

Discussion: Voice is the key

indicator of species limits in Turdus and relatives, as outlined in my

proposal on Turdus [m.] confinis. Between xeno-canto and Macaulay there are a

sufficiently large number of recordings from throughout the range of the assimilis-albicollis

group that someone could pick up where Boesman left off and do a formal

analysis of songs and calls to analyze species limits. Until that is done, I do not see how we can

change the status quo. On the one hand,

a preliminary inspection of songs suggests daguae is closer to albicollis

than to where we have it at present, in contrast to a genetic data set that

suggests that it is close to assimilis.

The weaknesses in both analyses make it unwise, in my opinion, to change

current classification for now, either in terms of taxon rank or relationships.

Recommendation: Too much uncertainty

remains, in my view, to make any changes, and so I recommend a NO on this one.

Note

on English names: Dagua Thrush has a track record and is the

only English name associated with the taxon.

Although Río Dagua was an important early collecting locality, it is

nonetheless a pretty obscure river in the greater scheme of things. Whether it’s worth changing to something like

Choco Thrush is at least worth considering.

This taxon’s range corresponds almost perfectly to the Chocó

biogeographic region and its plumage, darkest brown of any on the assimilis-albicollis

group, also reflects a prevailing Gloger’s Rule color trend shown by taxa

endemic to the region. On the other

hand, there are already 9 “Choco Somethings”, so at least Dagua Thrush is

novel.

Van Remsen,

October 2021

Comments

from Robbins: “NO. Without

further analyses of both genetic and vocal characters it would be premature to

treat daguae as a separate species.”

Comments from Lane: “NO. It is frustrating when an

otherwise good study makes one big blunder that severely weakens its punchline.

In Nuñez-Zapata et al (2916), it was the choice of taxa from Turdus albicollis

to include in the study. The samples of albicollis they used were one of

nominate from the Atlantic Forest and two of contemptus from La Paz,

Bolivia. Lowland Amazonian phaeopygius was not included, and this is the

taxon that sounds most like daguae from what I can tell. Furthermore,

whereas albicollis and contemptus are very similar in voice and plumage,

they differ strongly from phaeopygius (to the point that I'd say it's a

no-brainer that the former two should be separated from the latter at the

species level... the question is: where to fit the remaining northern South

American taxa?) the latter is the population that could well be sister to daguae.

The oversight of not including phaeopygius in the study badly damages

the conclusion that daguae should be separated as its own species.

Comments from Pacheco: “NO. Until a comparative vocal

analysis of assimilis/daguae/albicollis with appropriate

geographic coverage is done, I consider it equally premature to alter the

status quo.”

Comments from Claramunt: “YES. Evidence of

reciprocal monophyly is not strong but combined with clear phenotypic

differences in plumage and song, I see a strong case for separating daguae

from assimilis. I totally agree with Dan that the big picture may be

more complex and Amazonian albicollis may be closer to daguae

than to the true albicollis from the south. But I think separating daguae

is a step forward. Once we figure out the affinities of Amazonian albicollis

we can revisit this problem, but I think we don’t need to wait until we know it

all to improve our taxonomy of this complex.”

Comments from Areta: “YES. Nuñez-Zapata et al. (2016) have

provided convincing evidence that daguae is not part of albicollis

(I applaud that they have sampled nominate albicollis), and even if

their dataset is only of mitochondrial DNA it seems highly unlikely that this

pattern will be caused through introgression. Certainly more sampling of ssp.

of albicollis and a proper analysis of vocalizations can shed more

light. But the burden of proof is now on those wanting to treat daguae

as a ssp. of albicollis or of assimilis. Vocally, daguae

sounds different to any ssp. in the albicollis group (at least to my

ear), and the genetic divergence from assimilis (0.051; 1.35 Ma ago

[0.95 to 2.08]) seems to place it within expected distances between good Turdus

species. Biogeographically, it also makes sense to have this Chocó species

being more related to a Central American counterpart. So, although evidence is

not perfect, I prefer to treat daguae as a species on its own.

“Some

bits of information are still missing, but I think a fairly strong case can be

made to recognize Turdus

daguae for the following reasons: 1) Reciprocal monophyly despite

extensive sampling of assimilis,

including geographically distant samples [unfortunately, there are no samples

of daguae closer to the range of the southern subspecies of assimilis, but I don´t think

this will change the picture given the degree of divergence] and 2) distinctive

vocalizations: the song of albicollis

is remarkably constant across its geography (at least to my ears) and I have

never had trouble in identifying this species from Venezuela through NW and NE

Argentina and Brazil, this holds true to the east of the Andes in Ecuador (T. albicollis spodiolaemus),

differing remarkably from the higher-pitched, slower and differently patterned

song of daguae to

the west of the Andes in Ecuador. In this subjective and express analysis, I

agree with Boesman in that songs of assimilis

are the most distinctive, but daguae

seems to me consistently different from albicollis

as well; a thing that always bothers me on these HBW vocal assessments is their

lack of attention to detail and the impossibility of tracking down the

recordings used, which seriously undermines their use as a source of arguments.

I wonder why the apparently distinctive ssp. atrotinctus

was not sampled in the genetic analyses, it does look remarkably different in

plumage! Finally, it is clear that more thorough sampling of albicollis is needed

(sampling in Nuñez-Zapata et al. 2016 is very poor, and samples come only from

the southern range of albicollis),

but I don´t think that this will change the placement of daguae or the degree of

differentiation with respect to assimilis

(note that ssp. phaeopygus

and spodiolaemus

of albicollis in

Batista et al. (2020) are found as sister to assimilis,

which is relevant to the status of daguae).

Comments from Bonaccorso: “YES. Although the genetic

evidence is only mitochondrial, the differentiation is tremendous compared to

all other forms within T. assimilis, and I

agree with Nacho that it is very unlikely that the pattern is contradicted by

additional genetic evidence. Even though the T. a. daguae samples

are from Ecuador, I would not think sampling specimens from northern Colombia

would make a huge difference. I am no expert on vocalizations, but the songs of

T. a. daguae from Xenocanto sound

very different to the forms from Panama and Costa Rica. It is also interesting

that Xenocanto is treating T. daguae separately

from T. assimilis (I guess that is just IOC

taxonomy, but it makes sense to me). It seems that plumage color is not a very

good indicator of species status in this group of very similar taxa. Still,

that is what one would expect from a process of “cryptic” speciation, right?

Finally, this split makes perfect biogeographic sense.”

Comments from Stiles: “NO. Although I tend to agree

with Nacho and Santiago, I agree that there is still sufficient uncertainty

regarding both vocal and genetic data to reach a definitive conclusion. No

genetic data from the albicollis populations closest to daguae,

and while I suspect that tissue samples from Colombia might exist (Check

with Daniel Cadena and Andrés Cuervo). If so, these should be sequenced.

Likewise, need recordings of T. assimilis phaeopygus … so, NO pending

additional data.”

Comments

from Jaramillo:

“YES – Sure, more data are necessary, and some things are unclear. But it seems

to me that as Elisa, Nacho, and Santiago comment, there is enough here to

change the status quo. The status quo appears to be off; we may not quite know

how it is off, but I would rather make this change and adjust at a later date

than not do anything given the data we have.”