Proposal (924) to South

American Classification Committee

Recognize the genus Coeruleomitra for “Uranomitra” franciae

Effect on SACC: This proposal would

replace the genus name Uranomitra, as interpreted by Stiles et al. (2017: the generic nomenclature

of the Trochilini), based on Elliot (1879), with Coeruleomitra, because

Bruce and Stiles (2021) demonstrated that Uranomitra

and Leucolia were unavailable in

the combinations designated by Elliot (1879)

due to different, prior type species designations by Gray (1855, 1869).

Background: The revised

interpretations were partly influenced by a detailed study of the works of

George R. Gray (1808-1872) of the British Museum, particularly his The Genera of Birds (1844-1849), by one

of us, cf. Bruce (in press[1]). The relevant details

can be found in Bruce and Stiles (2021).

Uranomitra: Vieillot

(1817) named and described Trochilus quadricolor among the “colibrís”[2]. Vieillot (1822)

subsequently identified his Trochilus quadricolor of 1817 with Trochilus

mango Linnaeus, 1758; he then also

named and described a second Trochilus quadricolor, this time among the

“oiseaux-mouches”. Gray (1848) listed the first quadricolor as a synonym of T. mango,

and recognized the second quadricolor

as a species within his broad interpretation of Polytmus Brisson, 1760,

equating it with Lesson’s (1829) Ornismya cyanocephala, the only

subsequently named species at that time matching Vieillot’s circumscription.

In

March 1854, Reichenbach proposed the generic name Agyrtria, and within

this new grouping Uranomitra was

proposed as a subgeneric name, but without naming a type species.

In May 1854, Bonaparte proposed the generic name Cyanomyia, including

the same group of species but not quite in the same sequence, also without

naming a type species. Gray (1855)

clearly recognized that these two newly proposed generic names were identical,

and, treating Cyanomyia as the senior

name, by following Bonaparte’s subsequent synonymizing of Uranomitra under

Cyanomyia, designated the type species as Trochilus quadricolor Vieillot, 1822; thus Vieillot’s 1822 Trochilus quadricolor was applied to both

generic names. Cabanis and

Heine (1860) demonstrated that Uranomitra

was the senior name by dating the two generic names to the month in 1854,

with Cyanomyia as June 1854, but

revised to May 1854 by Heine (1863); the treatment of the names otherwise

following Gray (1848, 1855), with U.

quadricolor listed first. However, the 1822 quadricolor passed into

disuse, perhaps due to the recommendation of Salvin (1892), and was not used

after 1899, becoming a nomen oblitum (Art. 23.9.1, ICZN 1999). As

a consequence, Ornismya cyanocephala Lesson, 1829, as the senior,

available subjective synonym of Trochilus

quadricolor Vieillot, 1822, and as the first listed

species by Bonaparte (1854) also became the type species of Uranomitra,

per Gray (1855,

1869) based on his recognition at the time of the priority of Cyanomyia, under which cyanocephala Lesson “1832” [= 1829] was

first listed, despite a different sequence of species listed by Reichenbach

(1854) for Uranomitra.

This

interpretation was accepted by Ridgway (1911), Simon (1921) and Peters (1945),

although Peters demoted Uranomitra to a subgenus of Amazilia.

Thus, Elliot (1879) designating the type of Uranomitra as Trochilus

franciae Bourcier & Mulsant,

1846, had been pre-empted by Gray (1855; Art. 70.2 of ICZN 1999),

s.n. Cyanomyia. Several authors

including Stiles et al. (2017) followed Elliot’s designation of franciae,

but Gray’s earlier designation of cyanocephala must stand.

Recent

genetic evidence (McGuire et al. 2014, Stiles et al. 2017)

indicated that franciae is a phylogenetic outlier best accommodated in a

monotypic genus. The phylogenetic evidence also mandated the transfer of

cyanocephala to the genus Saucerottia Bonaparte, 1850, thus

rendering both Uranomitra and

Cyanomyia as subjective synonyms of Saucerottia. To

accommodate T. franciae as representing a monotypic genus, we proposed

the name Coeruleomitra (Stiles

& Bruce, in Bruce and Stiles 2021).

This

proposal covers the recognition of the genus-group name Coeruleomitra Stiles

and Bruce, 2021, to apply to Trochilus

franciae Bourcier & Mulsant, 1846, its designated type species, which

had been erroneously designated as the type species of Uranomitra Reichenbach

1854, by Elliot (1879).

Recommendation: We recommend a YES

vote.

References:

Bonaparte, C.L.J.L. (1850). Notes sur les Trochilidés. Comptes rendu hebdomadaires des Séances de l’Académie des Sciences,

Paris 30

(13): 379‒383.

Bonaparte, C.L.J.L. (1854). Tableau des oiseaux-mouches. Revue et Magasin de Zoologie pure et

appliquée (2) 6: 248–257.

Bruce, M.D. (in press). The

Genera of Birds (1844‒1849) by George Robert Gray: a review of its part publication, dates,

new names, suppressed content and other details. Zoological Bibliography 7 (1).

Bruce, M.D. & F.G. Stiles (2021). The generic nomenclature of the

emeralds, Trochilini (Apodiformes: Trochilidae): two replacement generic names

required. Zootaxa 4950 (2): 377-382.

Cabanis, J. & F. Heine. (1860). Museum Heineanum.

Verzeichniss der ornithologischen Sammlung des Oberamtmann Ferdinand Heine auf

Gut St. Burchard vor Halberstadt. Mit kritischen Anmerkungen und Beschreibung

der neuen Arten, systematisch bearbeitet. Theil III.

Die Schrillvögel, und die Zusammenstellung der Gattungen und Arten des 1‒3 Theils enthaltend. R. Frantz, Halberstadt. 221 pp.

Elliot, D.G. (1879). Classification and synopsis of the Trochilidae. Smithsonian Contributions to Knowledge

317: 1‒277.

Gray, G. R. (1848). The Genera of

Birds: Comprising their Generic Characters, a Notice of the Habits of each

Genus and an Extensive List of Species Referred to their Several Genera. Longman,

Brown, Green & Longman, London. Part 46: [103]‒[116], [195]‒[200],

[480]‒[483], pll. XXXV‒XXXVII, LIII, CXXa, 35, 53, 120*, 120(2).

Gray, G.R. (1855). Catalogue of

the Genera and Subgenera of Birds contained in the British Museum. Trustees

of The British Museum, London. iv + 192 pp.

Gray, G.R. (1869). Hand-list of

Genera and Species of Birds, Distinguishing those contained in The British

Museum. Part 1, Accipitres, Fissirostres, Tenuirostres, and

Dentirostres. Trustees of The British Museum, London. xx + 404 pp.

Heine, F. (1863). Trochilidica. Journal

für Ornithologie 11: 172‒217.

International Commission on Zoological Nomenclature [ICZN]

(1999). International Code of Zoological

Nomenclature. International Trust for Zoological Nomenclature. London. 4th

edition. xxx + 306 pp.

Lesson, R.P. (1829 [1829‒1830]). Histoire Naturelle des

Oiseaux-Mouches, ouvrage orné de planches dessinées et gravées par les

meilleurs artistes, et dédié A.S.A.R. Mademoiselle. Arthus Bertrand, Paris. xlviii + 223 pp., pll. 1‒85, 48bis.

McGuire, J.A., C.C. Witt, J.V. Remsen, Jr., A. Corl, D.L. Rabosky, D.L.

Altshuler, & R. Dudley. (2014). Molecular phylogenetics and the

diversification of hummingbirds. Current

Biology 24: 1-7.

Mulsant, M.E., J. Verreaux, & E. Verreaux. (1866). Essai d’une classification des Trochilidés ou

oiseaux-mouches. Mémoires de la Société

Impériale des Sciences Naturelles de Cherbourg (2) 7: 140–252.

Peters, J.L. (1945). Check-list of Birds of the World. Harvard University Press, Cambridge,

Mass. Vol. 5. xii + 306 pp.

Ridgway, R. (1911). The Birds of North and Middle America. Bulletin

of the United States National Museum 50 (5): xxiv + 859 pp. + 33 pll.

Reichenbach, H.G.L. (1854). Aufzählung der Colibris oder Trochilideen in ihrer wahren

natürlichen Verwandtschaft, nebst Schlüssel ihrer Synonymik. Journal für Ornithologie 1 [1853], Extraheft: 1‒24.

Salvin, O. (1892). Catalogue of the Picariæ in the Collection of the

British Museum: Upupæ and Trochili. In: Catalogue of the Birds in the British Museum, Trustees of the British

Museum, London. Volume 16: xvi + 703 pp,

14 pll.

Simon, E. (1921). Histoire Naturelle des Trochilidæ (Synopsis et

Catalogue). Encyclopédie Roret, Paris. vi + 416 pp.

Stiles, F.G., J.V. Remsen Jr. & J.A. McGuire. (2017). The generic

classification of the Trochilini (Aves: Trochilidae): Reconciling taxonomy with

phylogeny. Zootaxa 4353 (3): 401–424.

Murray D. Bruce and Gary

Stiles, October 2021

Comments

from Robbins:

“YES. I vote

yes for giving new generic names to those two hummingbirds, relying on those

two experts in sorting this out.”

Comments from Areta: “YES to recognizing the genus Coeruleomitra

for franciae for the reasons stated by Bruce & Stiles (2021).”

Comments from Lane: “To vote on this, I would like to

know what the source taxon of the tissue for the franciae was? Depending

on the population used, this causes a taxonomic conundrum that will result in

my giving the following answer: NO. My concerns are regarding which taxon was

used in the tree that establishes the placement of the species. My experience

with the three taxa within franciae suggests that there are probably two

distinct species involved (Peruvian cyanocollis and the two northern

forms: viridiceps and nominate) based on very different vocal

repertoires. Given that the McGuire et al. tree used an LSU tissue for this

species, it seems likely to be of cyanocollis, I am concerned that true franciae

was not included in the tree and may not be sister to cyanocollis (or

perhaps even to viridiceps?). This has important taxonomic implications

because it will mean, if my concern is true, that the new name will not refer

to franciae (sensu stricto), but rather to cyanocollis! I assume

that Bruce and Stiles (in press) will give "franciae" as the

type species for the genus in the description, but if that species is not

monophyletic, then how is this best resolved?”

Response

from Stiles:

“We noted the possible species distinctness of the S subspecies,

but unless it is so different as to require a separate genus (which I doubt), I

see no problem for Coeruleomitra as the substitute genus name we

propose. However, it would be nice to have genetic info for all 3 races to

evaluate this. Because Uranomitra

as described applies to the nominate race, only if genetic data were to show

that cyanocollis is distinct enough to merit generic separation would a

new generic name would be required.”

Comments

from Laurent Raty:

“As

noted in the proposal, Cyanomyia and Uranomitra were both

introduced with several included species and no original type fixation. In such

cases, the type can only be fixed by a subsequent designation (ICZN 69.1). The

Code is pretty clear that “subsequent designation”, in this context, means an

express statement, issued in a subsequent work, that one of the originally

included nominal species is the type of the nominal genus or subgenus (ICZN

69.1.1, ICZN Glossary: “designation, n.”); the Code also insists that the

meaning of the term “designation” is to be construed rigidly (ICZN 67.5). (And

it may also be noted here that the Code (ICZN 69.4) explicitly rejects

“fixation by elimination” – a method of type fixation which was widely accepted

in some circles in the late 19th-early 20th C, in which the type was deemed

fixed as a result of the subsequent exclusion of all but one of the originally

included species of the genus. This is consistent with the other provisions of

the Code: although such subsequent exclusions may indeed be seen as implying

that this last remaining species is the type, implying is not enough for the

ICZN – an express statement is always needed.)

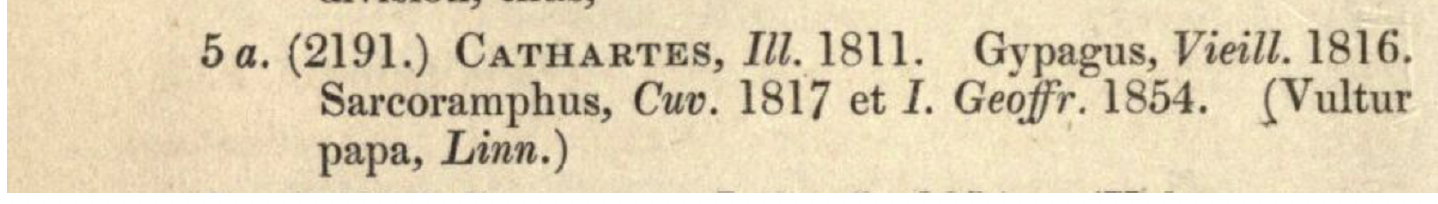

“The entry in Gray (1855: 139) which cites Cyanomyia and Uranomitra

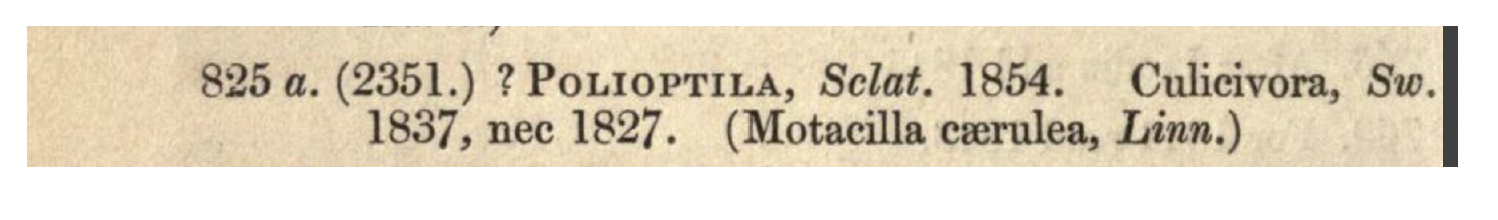

reads:

‘315 a. (2272.) CYANOMYIA, Pr. B. 1854. Uranomitra, Reichenb.

1854. (Trochilus quadricolor, Vieill.)’

“Of course, such an entry (two genus-group names, one species

name, no explanation) does not in itself constitute an express statement that

anything is the type of anything. Gray’s (1855) entries are type-species designations

only when viewed in combination with the Introduction of his book, where we

find, i.e., the following statements:

‘THE principal object of the present Catalogue is to give a

complete List of the GENERA and SUBGENERA of BIRDS, with their chief Synonyma

and Types. [...] The Genera are marked by an Asterisk, and those left unmarked

are to be considered only of subgeneric value.’

“This provides a key to parse Gray’s entries, which in the present

case yields : ‘315 a. (2272.) CYANOMYIA, Pr. B. 1854’ is a subgenus of

birds (which is placed under the full genus ‘*313. POLYTMUS, Briss.

1760.’ of p. 21); ‘Uranomitra, Reichenb. 1854.’ is the ‘chief Synonymon’

of Cyanomyia; ; ’Trochilus quadricolor, Vieill.’ is the type of Cyanomyia.

This tells us absolutely nothing about the type of Uranomitra, however:

two genus-group names can perfectly be synonyms without having the same type;

and there is no express statement anywhere in Gray’s book, to the effect that

the species cited in his entries would also be the types of his ‘chief Synonyma’.

As a consequence, under the rigid interpretation that the Code imposes, Gray

designated a type for Cyanomyia, but he cannot be construed as having

designated one for Uranomitra. The first author who actually did this

was Elliot (1879: 195), who, as correctly noted in Stiles et al. (2017),

designated Trochilus franciae Bourcier & Mulsant, 1846. There are no

reasons to regard this designation as invalid and, therefore, I can see no

problems with how this name is currently used in the SACC list.

“(Re. Dan’s concerns about the monophyly of Uranomitra franciae:

the sample used in McGuire et al. (2014) was LSUMZ B12063; this is given by

Kirchman et al. (2010, Biol. Lett., 6: 112-115) and Hernández-Baños et al.

(2014, Rev. Mex. Biodiv., 85: 797-807) as being from Pichincha Province

in Ecuador and should thus be viridiceps. It may be worth to note, here,

that Ornelas et al. (2014, J. Biogeogr., 41: 168-181) sequenced ~1200 bp

of mtDNA from two other samples of U. franciae, LSUMNS B-12179 from

Pichincha, Ecuador (= viridiceps), and LSUMNS B-33360 from Cajamarca,

Peru (= cyanocollis) – these two samples did not emerge as sister in

their trees, one of them appearing closer than the other to what is currently

called Chrysuronia in the SACC list. The support for these relationships

was poor, however.)”

Comments from Pacheco: “NO. The nomenclatural assessment

of the case by Raty, with which I agree, forces me to vote No. Raty states: “The first author who actually did this [designated type species

for Uranomitra] was Elliot (1879: 195), who …designated Trochilus

franciae Bourcier & Mulsant, 1846. There are no reasons to regard

this designation as invalid. and therefore, I can see no problem with how this

name is currently used in the SACC list.”

“For this reason, Coeruleomitra Stiles and Bruce, 2021

becomes a junior synonym of Uranomitra.”

Comments

from Claramunt:

“NO. Raty’s explanation makes sense. Trochilus franciae is the type of Uranomitra

(designated by Elliot 1879). It is not clear that Gray designated cyanocephala

previously.”

Comments

from Piacentini:

“NO to the replacement of Uranomitra by its

(new) junior synonym Coeruleomitra. I totally agree with Raty's

comments. I copy below the relevant part of an email exchange by the time the

paper was published, which may be useful for SACC's webpage.

“’>>>>>>>

The case for Uranomitra is clear-cut: the fact that it was mentioned as a synonym of Cyanomyia by Gray does not make it "inherit"

the type fixation of Cyanomyia.

There is just no base to assume it according to the Code. A type fixation must

be rigidly construed (art. 67.5), and the union of two genus-group name as one

genus-level taxon does not make any difference for the definition of their

respective type species (art. 67.10, for a parallel reasoning).

Here is Gray's relevant page: https://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/page/17136778 (see 315a)

Thus, the following sentence (Bruce &

Stiles, p.378) "Gray (1855: 139) synonymized Uranomitra under Cyanomyia, and thus by subsequently

designating the type species of Cyanomyia as Trochilus quadricolor Vieillot, 1822, this also became the type species of its synonym, Uranomitra" finds no support in the Code.[bold added]

The type species of Uranomitra, to the best of my knowledge, was first

and subsequently fixed by Elliot in 1879, which designated Trochilus franciae Bourcier & Mulsant. Period. The name

therefore applies to "Amazilia" franciae, and the unnecessary just-proposed new genus Coeruleomitra Stiles & Bruce is a junior objective

synonym of

Uranomitra.

<<<<<<<’”

Comments

from Stiles:

“Murray is preparing a rebuttal to Raty, basically showing

that the documented historical context

has been ignored. So let´s wait until

these data are presented by Murray before making a final decision.”

Comments from Murray Bruce and

Stiles in response to those of Laurent Raty: “Why Raty opted

to ignore the historical context of the case, as summarised

where relevant by us, remains surprising, except that by doing so, he is no

longer tied to considering what actually happened. Instead, he is free to raise unnecessary

speculation that may sound feasible. But

why ignore the well-established facts?

“The relevant historical context omitted

by Raty can be summarised thusly (see our paper for

further details; relevant references also cited with this proposal): In 1854

Reichenbach and Bonaparte published competing classifications of

hummingbirds. They both recognised one particular group of species as sufficiently

distinctive to require the proposal of a new genus-group name to distinguish

it. Reichenbach proposed Uranomitra, while Bonaparte proposed Cyanomyia. Indeed, no type species was designated by

either author. In 1855 Gray included

both names in his revised list of avian genera and subgenera. Gray adopted Cyanomyia and listed Uranomitra

as an objective synonym. As would be

evident from examining the 1854 papers of concern here, both names applied to

the same species and therefore one would be an objective synonym of the

other. Gray clearly knew this. However, although Gray chose to use what was

soon revealed as the junior name, his selection was because Bonaparte’s name

was proposed at the generic level, while Reichenbach’s was added as a

subgeneric name. This interpretation

apparently accords with the view of his brother and boss at the British Museum,

J.E. Gray, who wrote the introductory remarks in the 1855 catalogue, quoted by

Raty, and who opposed G.R. Gray adopting the recently proposed international

rules of nomenclature.

“Indeed, there was no ‘express statement’

of a ‘subsequent designation’ because Gray was following his own rules and did not

adopt those proposed as international rules in 1843. However, what may be seldom appreciated is

that the current Code, in operation since 1961, as revised three times, and

also adapted from the earlier sets of rules, makes allowances for what can be interpreted

as pre-Code nomenclatural acts. Gray’s

type species interpretations in 1855, and in his earlier editions of lists of

genus-group names going back to 1840, are widely accepted as sources of both

original and subsequent type species designations despite lacking the wording

subsequently demanded by the Code. Note

that in the Code some articles make such distinctions with before and after

dates that also help to distinguish the pre-Code and early Code periods from a

time when the Code was universally accepted and followed (e.g., ICZN 12 &

13). Further to this, and contrary to

Raty, type selection by elimination, as discouraged under the Code (ICZN 69.4),

and as used earlier by some authors, was not Gray’s method of subsequent type

species selection and designation. As

later explained in a publication we cited, Gray selected the first species

listed, should there be more than one.

Bonaparte’s first listed species is [Ornismya]

cyanocephala; it also could be

regarded as the original designated type species, based on the obvious

alliterative link in the proposed new genus-group name, thus Cyanomyia cyanocephala. Reichenbach’s first listed species is Trochilus franciae. In this instance,

Gray seemed not to follow his own method but actually he did. Gray had earlier (1848) recognised

Trochilus quadricolor Vieillot, 1822,

not 1817, as identifiable with Ornismya

cyanocephala Lesson, 1829, and thus the senior name. In 1855 Gray obviously designated the same

type species to Uranomitra because

Gray recognised it as an objective synonym of Cyanomyia. There is much to tell from

Gray’s listing in 1855, rather than “absolutely nothing” as argued by

Raty. Elliot’s later designation of Trochilus franciae as the type species

of Uranomitra was by applying Gray’s method. Elliot, however, either overlooked or

misunderstood Gray’s earlier action in 1855 in designating quadricolor to both genus-group names, by treating quadricolor as the senior species-group

name for the first listed cyanocephala. Note that in 1854, both quadricolor and cyanocephala were

listed as separate species by both Bonaparte and Reichenbach.”

“In 1860 Cabanis & Heine (Mus.

Hein., 3, p. 41) dated Reichenbach’s paper to May 1854 and Bonaparte’s to June

1854. However, in 1863 Heine corrected

the dates to March (Reichenbach) and May (Bonaparte). Cabanis & Heine also first corrected the

genus-group name sequence and used Uranomitra,

with “Cyanomyia (!)” listed as the objective synonym. They also recognised

the same type species for both names, indicated by listing quadricolor first. Their

first listing of the type species in sequence actually demonstrates a form of

shorthand to indicate the type species, as extrapolated from Gray’s selection

method of choosing the first originally listed species as type. It should be noted that very few subsequent

type species designations antedate Gray’s lists, and as all were compiled by

using Gray’s own rules of nomenclature, Gray’s first species rule is one of the

earliest for subsequent type species designations.

Later, Ridgway in his major work (vol.

5, 1911, p. 406), recognised that in 1855 Gray had

subsequently designated Trochilus

quadricolor as the type species of both Uranomitra

and Cyanomyia. This interpretation was followed by Simon

(1921, p. 325) in the most recent hummingbird classification wherein all known

names were included. Peters did not list

these two names because, under his editorial policy, as they had been

previously synonymised by Sharpe in his Handlist (vol. 3, 1900, p. 108), they

would be omitted.

“Both nominal genus-group names can have

the same type species when they are objective synonyms (ICZN 61.3.3). Therefore, both Uranomitra and Cyanomyia have

the same type species, recognised as being

subsequently designated by Gray in 1855, and this interpretation was supported

by the most recent standard authorities covering the status of both names. Both genus-group names, although established

without using Code rules, meet the requirements of being acceptable by use of

one or more available species-group names in combination, and by indication

(ICZN 12.2.5, 12.2.6; names published before 1931). Thus ICZN 67.5 does not negate the subsequent

type fixation despite not having the explicit wording subsequently

required. ICZN 69.1.1 is met because it

is clear that the author (Gray) accepts the type species given as its

subsequent designation for both genus-group names Uranomitra and Cyanomyia. However, contrary to Raty, ICZN 69.4 does not

apply as the type species was not fixed by elimination but by the selection of

the first species listed in the case of the genus-group name adopted by Gray (Cyanomyia), and thus the objective

synonym (Uranomitra), as recognised by Gray, would share the same type species.

“We

therefore wish to confirm that Coeruleomitra

is available, with Trochilus franciae

as its type species.”

Comments

from Jaramillo:

“YES – Based on Bruce – Stiles rebuttal. Unless there is a major flaw here that

someone better equipped to work through nomenclatural issues, and how to apply

the Code, than I can offer?”

Comments from Lane: YES to

recognizing Coeruleomitra

for “Uranomitra” franciae. However, I would like to go on

record to say that the three taxa currently assigned to that species (franciae,

viridiceps, and cyanicollis)

need to be phylogenetically assessed with respect to one another, as I suspect

that, at the very least, cyanicollis

will be found to be specifically distinct from the other two. In

addition, given that the taxonomy within the “Amazilia” group has

undergone severe upheaval (as this very proposal illustrates!), and that

generically valid morphological characters seem to be minimal (at least to my

eye), it would be best to sample all three taxa to make sure they are in fact

sisters, and don’t fall in different genus-level clades. This was my concern in

my first comment above: since the taxon sampled wasn’t the nominate, using that

result to assign “franciae” as the type of the genus may not accurately

represent the phylogenetic relationships of

franciae (sensu

stricto) with respect to other genera within the larger clade.”

Additional

comments from Claramunt: “My vote is still NO.

“1) From what I see in

the rest of the list, Gray (1955) is only mentioning (between parenthesis and

at the end of every entry) the type species of the generic name he considered

valid. He is not listing the type species of any of the synonyms. Therefore, in

the case of the hummingbird, he is implying that the type species of Cyanomyia

is Trochilus quadricolor. But nothing can be inferred about the type

species of Uranomitra. Laurent is right. Lots of hypotheses and

inferences can be made from the historical context, but at the end of the day,

we have to follow the rules of The Code.

“2) The fact that two

names are applied to the same group of species does not make them objective

synonyms. They can be subjective synonyms. For two generic names to be objective

synonyms they must share the same type species (Art. 61.3.3 and Glossary),

which doesn’t seem to be the case for Uranomitra and Cyanomyia.”

Additional

comments from Piacentini:

“Bruce said: ‘Both nominal genus-group names can have the

same type species when they are objective synonyms (ICZN 61.3.3). Therefore, both

Uranomitra

and

Cyanomyia

have the same type species.

“This is incorrect. Being objective synonyms is a

consequence of having

the same type, and not an a priori

assumption as clearly

interpreted by Bruce in his papers and comments. So, the first question is: ACCORDING

TO THE CODE (and NOT according to [questionable] historical context over a

century before the first edition of the Code), what is the type of

Cyanomyias? (answer:

Trochilus quadricolor, subsequently designated by Gray,

1855). And what is the type of Uranomitra? (It is

Trochilus franciae, subsequently designated by

Elliot, 1879). Since quadricolor

and franciae

are regarded as distinct species, and since they belong to

distinct lineages afforded independent genera status,

Cyanomyias

and Uranomitra

are not synonyms (less so objective synonyms).

“Bruce himself acknowledges that his interpretation of type

fixation for Uranomitra does not

have follow the Code, stating: ‘(...) despite not having the explicit wording subsequently required’. That is precisely the point. The

Code requires explicit wording for type fixation, and Gray does not do it for Uranomitra.

This ends any further discussion.

“Bruce ends his comment with ‘We therefore wish

to confirm that Coeruleomitra is available, with Trochilus franciae as its type species’. There is

no question here. Coeruleomitra is indeed

available for

franciae. And so is Uranomitra. With both

genus names having the same type species,

they are

objective synonyms. And, according to the principle of priority,

Uranomitra is the

valid name.”

Additional comments from Robbins: “Based on Victor’s

comments and the taxonomic concerns expressed by Dan, I change my vote to NO.”

Additional comments from Lane: “I would like to change to

NO based on the comments by Vitor, and Santiago. This also makes me feel better

regarding the phylogenetic issue that has been causing me sleepless nights.”

Comments from Frank Rheindt (voting for Zimmer): “The

question regarding the type species of Uranomitra is a convoluted one.

Clearly, a lot of research has gone into this by Bruce & Stiles (2021 and

subsequently), and valid points have been raised by Laurent Raty. I find myself

in partial agreement with both sides. I would appreciate the chance of weighing

in on this. There are two core questions:

1.

Should type species statements in catalogues

such as Gray’s Genera of Birds be considered “rigidly construed type

species designations”?

“This is a difficult question, and I am not sure there would be a

unanimous answer even among Commissioners of the ICZN. The wording of the

Code’s Article 67.5 implies some “rigidity” in how a type species must be

designated, meaning there cannot be any doubt as to what the author may have

meant. On the other hand, there is a long-standing tradition in various

zoological communities (mostly in invertebrates) to accept catalogue statements

as type designations, especially if these are historically important catalogues

and a wide acceptance of these type designations has built up over the decades.

An example is d’Orbigny’s Dictionnaire Universel d’Histoire Naturelle,

published in multiple installments from 1839 to 1849, which contains numerous

type species designations for Diptera (flies) that continue to be accepted.

Indeed, a sudden rejection of all these type species designations would

probably lead to substantial taxonomic chaos and instability. The Commission is

generally quite reluctant to insert itself into long-standing taxonomic

traditions of particular zoological communities and will rarely tell them what

should and should not count as a designation in such borderline cases.

“Catalogues are necessarily compact in their format and lack

detailed statements. The most important factor, in my opinion, is whether the

format allows for unequivocal interpretation of the author’s intent. In this

case, a close reading of Gray’s introductory statements makes it clear that the

species in brackets refer to what Gray assumed or intended to be the type

species.

“If the Commission were asked whether this sort of statement is a

valid type designation, my guess is that the majority of Commissioners would

feel reluctant to opine on this and would hope for the ornithological community

to come to its own consensus on whether such an important book as Gray’s

catalogue contains valid type species designations or not. Based on the

statements by Murray and Gary, who have a much deeper understanding of this

catalogue than I do, I would tend to err on the side of accepting type species

designations in important historical catalogues such as Gray’s.

“But as we shall see below, thankfully this question is only

tangential to resolving the present case, and we don’t need to worry about it

here.

2. Are Cyanomyia and Uranomitra objective

synonyms?

“No, they’re not. The Code’s Glossary definition of “objective

synonym” stipulates that the genera in question must have identical type

species. This is regardless of whether the originally included species are

identical or not. If Gray’s type designation for Cyanomyia is accepted, Trochilus

quadricolor is its type species, but that still leaves Uranomitra

without a type. The first available type designation for Uranomitra

eems to be Elliott’s (1879), who chose Trochilus

franciae, which makes the two genera subjective (not objective) synonyms,

as has been pointed out by others. Hence, the species Trochilus franciae

is the type of Uranomitra and does not require a new genus name, and any

name proposed to that end becomes a junior synonym.

“My comments do not address the equally important issue raised by

Dan Lane, namely whether the three taxa currently placed within Uranomitra

franciae are monophyletic or not. I agree this requires urgent resolution.

At the same time, even if there are multiple species-level taxa within Uranomitra

franciae, I hope they will not fall into different generic groups, as that

would be the only way in which their species-level taxonomy could conflate our

genus delimitation.

“I hope these comments are helpful, and I appreciate any criticism

that may point to mistakes in my reasoning.”

Additional

comments from Areta:

“Thanks Laurent, Vitor, and Frank for your input on

this very instructive case. My vote was cast early on, and I did not have a

chance to revisit this. Based on these clarifications, I change my vote to NO.”

Additional

comments from Jaramillo: “I change my vote to NO, having

others step in and detail some of these issues has been good. One needs to be

akin to a constitutional scholar to understand some of these nomenclatural

issues.”

Comments from Steven Gregory (voting for Bonaccorso): “NO. I broadly agree with Laurent Raty, and the

salient points are:

“1. Uranomitra

Reichenbach, 1854, was introduced with four included nominal

species, franciae, quadricolor, cyanicollis,

and cyanocephala.

“2. The Code (ICZN, 69.1.1 and 67.5) is very clear about

subsequent designation and that 'designation' must be rigidly construed. The

inclusion of Uranomitra

Reichenbach, 1854, as a synonym of

Cyanomyia Bonaparte,

1854, by G.R. Gray (1855: 139) does not confer the type species of the latter

upon the former.

“3. The first to correctly designate a type species for

Uranomitra was Elliot

(1879: 195), who designated franciae

Bourcier & Mulsant, 1846.

“This was further supported by the comments by Piacentini, with

which I concur. Coeruleomitra

Stiles & Bruce, 2021, becomes a junior objective synonym of

Uranomitra Reichenbach,

1854. A 'no' vote, as defined by the SACC proposal 924.

“While Murray Bruce is correct in his rebuttal that (obviously) no

rules other than the British Association 'Strickland' Rules (1842) were then

available, and which had little to say on subsequent designation as such, Gray

did, clearly, have a system, and those names spelled out in small caps were

those to which the type species, in brackets at the end of the entry, applied.

Thus in the entry on p. 139 the type species (Trochilus quadricolor,

Vieillot) applies to "CYANOMYIA Pr. B.

1854", and not any name (Uranomitra)

listed as a synonym.

“Were Bruce's method of interpreting G. R. Gray's works to be

widely adopted, numerous genera listed in synonymy by him would have to have

earlier and different type-species from those currently understood to be

correctly designated elsewhere. There is no 'case law' in Zoological

Nomenclature, but this would nevertheless be a dangerous precedent to

establish.

“The correct type of Cyanomyia

Bonaparte, 1854, is a completely separate issue, with

'Trochilus quadricolor, Vieillot', being an apparent

nomen oblitum (Art. 23.9.1) and the subsequent designation, again by Elliot

(1879: 195) of Trochilus

cyanocephala Lesson,

1830, the first nominal species listed by Bonaparte, being generally accepted.”

Response from Bruce and Stiles:

Reply to recent

comments plus a recap on Coeruleomitra

“We already have presented three discussions of the

relevant details supporting recognition of Coeruleomitra. The only significant change since our earlier

discussions is that the review of G.R. Gray’s The Genera of Birds (1844-1849) cited to Bruce in press, was

published in February (see http://hbs.bishopmuseum.org/dating/sherbornia/issue8.html).

Therein important details explaining Gray’s own rules and methods with

nomenclatural issues, including type selection, were discussed in the

introductory section. Such an

understanding of how Gray developed his work on avian genus-group names over

the period of 1840-1871 helps with interpreting what he sought to do with the

1855 catalogue, the source of the type selection issue that continues to

concern the current proposal. As noted

in the Gray review, this 1855 catalogue was a continuum in his series of

publications focused on avian genera.

Indeed, while his 1840 list and its 1841 revision and 1842 supplement,

along with the 1855 catalogue, are major sources of accepted subsequent type

species designations by Gray, his connection of generic names to their type

species runs through all his lists and catalogues, as also seen in particular

in his major monograph The Genera of

Birds (1844-1849) and his world ‘Handlist’

(1869-1871), each consisting of three volumes.

“Also as discussed in the Gray review, Gray

followed his own rules. Although

international rules were promulgated from 1842, Gray stuck to his own in all

his publications. The various sets of

personal nomenclatural rules used before we had international rules, and indeed

for the decades from the 1840s before international rules finally became

universal, by the time of the official Règles of 1905,

often had particular views of how names should be used, or not used. Going back to those first altering the

Linnaean structure, none explained their rules, but something of what they were

doing could be gleaned from their writings.

G.R. Gray was unusual in that he published details of his rules of

nomenclature, around 1871, but privately, and anonymously, in the third person,

and as it turned out, not long before he died in 1872. Moreover, it revealed that some of his rules,

such as the ‘first species’ rule, had been very influential and widely followed

for decades.

“It is all the more significant because a perusal

of the Peters checklist volumes demonstrates that Gray’s works noted above,

particularly for 1840, 1841 and 1855, are the senior publications from which

formal, subsequent type species

designations are recognised and cited. Peters was influenced by the work of J.A.

Allen in 1907-08 based in particular on his study of the type species of the

genera of North American birds, wherein Allen gave due credit to Gray as the

source of the earliest subsequent type species designations. Thus a perusal of the Peters checklist

volumes, including those completed by Peters’ successors, reveals wide usage of

these Gray publications.

“As Gray outlined in his 1871 pamphlet, his method

of type species designation followed the ‘first species’ rule. Gray’s pioneering work on summarising

and assessing avian generic names in the 1840s and later was very influential

in its day; and all based on Gray following his own rules. Strickland, a critic of Gray’s first list of

avian generic names, was primarily influenced to seek to establish

international rules of nomenclature because of his concerns about nomenclatural

chaos within ornithology. Ornithology

continued as a major influence on how international rules evolved. Their wide acceptance came in particular with

the Règles

of 1905.

“However, the contentious issue of subsequent type

species designations particularly that of the ‘first species’ rule vs.

selection by elimination was considered unresolved in the 1905 rules. It soon became a topic of an extended debate

in Science in 1906-1907, initiated by

ornithologists Witmer Stone and J.A. Allen.

The upshot was a revision of Article 30 of 1905 on the designation of

type species, connected to an extended series of recommendations. Amongst them

was recognition of the ‘first species’ rule. With only slightly revised

wording, Art. 30, recommendation (s), is now represented by Art. 69A.9 of the

1999 Code. While recommendations are not

rules, an important function is historical context. The Code not only provides rules to aid with

naming animals, but also it is a bridge linking names and nomenclatural acts

established under international rules with those names and nomenclatural acts

established before there were international rules, and equally if not more

importantly, during the decades of transition when the international rules, as

they evolved, was but one of many sets of rules guiding nomenclatural

acts. Thus it is important to see the

dual role of the Code, i.e., reconciling past nomenclatural acts under

different rules with those under international rules.

“In other words, as in the case before us in

Proposal 924, based on historical context, Gray’s actions in 1855 fall within

the scope of what is covered by the Code.

An important point being that in such accepted designations outside of

the international rules, explicit wording was not yet a requirement. A comment by Raty here is misleading because

the type was not fixed by elimination but by simply applying the ‘first species’

rule, and as such there was no implication but actually an express statement

because the species selected was the first species listed in the original

source of the name and as such, in the case under consideration here, also

would apply to an objective synonym. If

explicit wording is to become a retrospective requirement then it can be argued

that it could lead to a reassessment of many names where such explicit wording

is absent, yet the type designations are widely accepted. One must bear in mind that requirements for

explicitly stating a type species designation came much later, particularly as

linked to the 1905 rules, although as we’ve seen here, the matter still needed

some finalisation.

“Let us herewith briefly consider again the relevant

points (this both revises and supplements our previous comments):

●

In 1854 within two months two rival classifications of hummingbirds were

published, Reichenbach in March, Bonaparte in May. Both recognised the

same group of species as warranting a name.

Reichenbach proposed the subgenus Uranomitra,

Bonaparte the genus Cyanomyia. No type species was indicated, although

arguably in the case of Bonaparte, the first listed species named cyanocephala was implied by the partial

homonymy of the names. Also in 1854

Bonaparte subsequently linked the two names, giving priority to his own

name. The publication dates of the two

names were clarified later.

●

In 1855 Gray listed both names together in his Catalogue because he also clearly recognised

both as applying to the same group of species.

His choice of Cyanomyia, with Uranomitra as the objective synonym, was

not about any confusion of publication dates.

Gray gave priority to Cyanomyia

because it was proposed as a genus, whereas Uranomitra

was proposed as a subgenus. As a

consequence, both names were linked to the same type species, which Gray recognised as Trochilus

quadricolor Vieillot, 1822. Although

there is a Trochilus quadricolor

Vieillot, 1817, Gray recognised both names because at

the time they represented different species in different genera. However, the junior homonym was subsequently

replaced with the next available name, Ornismya

cyanocephala Lesson, 1829, as recognised by

Bonaparte, and thus the designated type species for both generic names.

●

If one chooses to dispute the connection as given by Gray and argue that

his type designation only applies to Cyanomyia,

although no explicit indication by Gray, then following the nomenclatural

history of the names we turn to the next relevant publication. In 1860 Cabanis & Heine followed Gray,

notably with the first species listed following the ‘first species’ rule, but

therein recognising the seniority of Uranomitra over Cyanomyia, and maintaining the connection of both names to the same

type species, as by Gray. Again, no explicit wording, but also an express

statement through the ‘first species’ rule by following Gray, as intended, to

be covered by the recommendation in the rules and later the Code. The

publication dates indicated for Reichenbach and Bonaparte were corrected by

Heine in 1863.

●

All subsequent major works on hummingbirds followed Gray, culminating with

Ridgway on North and Middle American birds (1911), and Simon’s monograph of

1921, the last time all known names applied to hummingbirds were listed. Peters is no help on the two names concerned

because, according to his editorial policy, they already had been synonymised and thus not to be listed in the relevant

checklist volume. This absence of

relevant documentation in such an oft-cited reference, even though all details

were provided by Ridgway and Simon earlier, was not helpful to most users of

the checklist, as this case demonstrates.

●

The treatment of Uranomitra by

Elliot in 1879 was due to a misunderstanding that was not explained and not

followed.

●

Some of the above discussion also clarifies a point disputed by

Piacentini. Historical context does

matter because the earlier rules, particularly from 1905, and then the Code

from 1961, were also revised constructs to reconcile what went before with what

was done under international rules. The

linking of the two names, making Cyanomyia

an objective synonym of Uranomitra,

was first established in 1854, accepted by Gray in 1855, with priority and

dating corrected by Cabanis & Heine in 1860 and 1863. While the Code does require explicit wording

now, the whole point of the recommendations and the Code reconciling with past

actions not based on international rules and thus an absence of explicit

wording was in the interests of nomenclatural stability. The recognition of both names as applying to

the same type species is a well-documented fact within the relevant

ornithological literature.

●

Rheindt’s comments about the role of past

catalogues and explicit wording and potential chaos fits with some comments

above.

●

Rheindt also considered whether or not Cyanomyia and Uranomitra are

objective synonyms. What is apparently

overlooked here is that the first and most obvious evidence of this connection

is by the reversal of the names based on priority by Cabanis & Heine in

1860, with the same type species listed first, following Gray. As demonstrated by Ridgway and Simon as the

latest authorities covering the names in question, the link to the same type

species for both Uranomitra and Cyanomyia, following Gray, was not

questioned by them, and thus subsequently accepted by Peters.

●

Once again we believe we have presented a strong case for the acceptance of Coeruleomitra as the available generic

name with type species Trochilus franciae

Bourcier & Mulsant, 1846.

“For the first time in our discussion we can cite

Bruce’s review of Gray’s The Genera of Birds as an available

publication, containing a discussion of Gray’s rules on nomenclature. With access we hope it helps in understanding

how Gray interpreted the generic names.

Moreover, some additional historical background is provided as a reminder

that for all the clinging to exact wording in Code articles, we must bear in

mind that the Code also was intended to have a dual role in reconciling

nomenclatural acts not covered by the international rules with how the

international rules were subsequently applied.

“In this particular case, to argue against what

Gray intended is also to argue against what has long been accepted in the

relevant ornithological literature. It

is worth emphasising that where the imprimatur of a

Peters checklist volume is missing when one wishes to determine the status of a

name, with one then required to delve further back, then that is where problems

may arise. What Peters intended by

omitting names previously synonymised was that he was

following what was done earlier. In this

case it was Ridgway and Simon, key works also cited by Peters. Clearly, if Peters disagreed with an earlier

interpretation he would have listed the names differently, but if not, it can

be implied that he agreed with the previous interpretation. This point seems to be lost on current users

of his work.

“If Peters had listed the names we would not be debating

this topic at all, and a new generic name for franciae would

be obvious.”

New

Comments from Frank Rheindt (voting for Zimmer): “NO.

“Rationale:

It was a great pleasure to read Bruce & Stiles’s latest

response to previous votes. Their work on Gray’s catalogue is clearly

important, and I am looking forward to reading Bruce (2023), which did not seem

to be available at the time I’m writing this. Understanding the historic

context that reigned at the time when a nomenclatural act was made is very

important. A large percentage of zoology’s nomenclatural acts were made at a

time when Code rules didn’t exist, and the framers of the Code have been

careful to avoid discrepancies that might lead to the rejection of

widely-accepted older names because of the adoption of new rules. I thoroughly

enjoyed reading Bruce & Stiles’s scholarly explanations of Gray’s own

nomenclatural practices and rules, and I learned a lot that I didn’t know

before.

“At the same time, I feel compelled to vote NO on their request to

implement Coeruleomitra a genus

name for franciae. The

reason for that is that Gray never designated a type species for

Uranomitra. He clearly only designated a type species for

Cyanomyia, allowing

Uranomitra to remain

available to serve as the senior genus-group name for the taxon

franciae.

“Gray’s pre-Code practices and their present-day acceptance:

Despite the words that have been exchanged, I think very few

people in this debate would want to belittle the importance of Gray’s catalogue

and his practices. Bruce & Stiles expend a lot of effort to discuss the

importance of Gray’s practice of affording the first-named species type status,

and that is great. It doesn’t really matter which rule Gray adopted; the

important thing is that we all continue to honor his practice and recognize his

nomenclatural acts. For instance, the sort of type designations that Gray

practiced (by placing a type species in brackets) would no longer be acceptable

if carried out in 2023, because the Code demands modern type designations that

are rigorously construed. But when it comes to pre-Code names, users of the

Code close one eye and allow for such practices, provided that they enjoy wide

acceptance in the community. Even Bruce & Stiles’s fiercest critics in this

debate didn’t disagree about the validity of Gray’s designation of

Trochilus quadricolor as type

species for Cyanomyia. And this

should serve as a reminder for all of us that – in fact – we do honor pre-Code

practices and tolerate them in ways that we wouldn’t tolerate acts carried out

in 2023.

“But Gray’s practice must be explicit for us to recognize it:

We can only honor and tolerate such pre-Code practices where they

have been explicit, such as Gray’s type designation for Cyanomyia. What

Bruce & Stiles ask us to do now is to extend that tolerance to Uranomitra, even

though this genus-group taxon was never listed by number in Gray’s catalogue.

Bruce & Stiles arrive at the conclusion that

Uranomitra must be an

objective synonym of Cyanomyia

because they were described on the basis of the same group of

species, even though this defies the definition of “objective synonym” as per

Code Glossary. I wonder how Bruce & Stiles are so confident that Gray

didn’t list Uranomitra as a

subjective (rather than objective) synonym?

“Gray lived before the time that the Code existed, and it is

highly questionable whether the modern Code concepts of “objective versus

subjective synonyms” would have ever featured in Gray’s thinking. I feel Bruce

& Stiles ask too much of us when declaring that “…Uranomitra

is an objective synonym of

Cyanomyia, hence Gray’s intention was to assign his type

species to both of them…”. Firstly, this type of thinking ignores the true

definition of objective synonym, and secondly, how can we be so confident that

this was Gray’s intention? In the hundreds of instances where he lists “chief

synonyms”, are they always automatically objective synonyms with identical type

species? Surely not…

“Works subsequent to Gray’s catalogue do not salvage the case:

Bruce & Stiles go on to say that – even if we disregard Gray’s

questionable type species designation for

Uranomitra – Gray’s

intent was reconfirmed by subsequent authors, most notably Cabanis & Heine

(1860). To be sure, Cabanis & Heine (1860) and any other publications are

independent works and have to stand on their own two legs for a nomenclatural

act to be accepted. I have scrutinized Cabanis & Heine (1860; III. Theil),

but apart from listing the two genera (Uranomitra, Cyanomyia) in a

corrected sequence of priority, there is no sign anywhere that the authors

attempt to clarify the type species designation for either name. The authors do

make occasional statements about type species designations in their footnotes,

but not for these two genus-group names. I have also perused the entire

Introduction, written by J. Cabanis in archaic German in the 1. Theil, to glean

any potential information on whether the authors set out to indicate type

species identities with particular practices, but there is no indication

anywhere. Hence, we cannot just use Cabanis & Heine (1860) – or any

subsequent publication for that matter – to justify the intention that Gray may

or may not have had.

“Summary:

In summary, I acknowledge Bruce & Stiles’s main point that

historic context is very important in making sense of nomenclatural acts, and I

feel we (=the community) are largely doing so by tolerating old practices that

would no longer be OK today, such as formulaic type species designations in

catalogues. But this tolerance should not extend to recognizing designations

that were never explicitly made, and that may or may not have been the intent

of the original author.”

New

comments from Claramunt: “At the risk of repeating the

same arguments, here are some comments on B&S rebuttal:

B&S: “In 1855 Gray listed both names together

in his Catalogue because he also clearly recognised

both as applying to the same group of species.

His choice of Cyanomyia,

with

Uranomitra as the objective synonym, was not about

any confusion of publication dates.”

“The linking of the two names, making Cyanomyia an objective synonym of Uranomitra, was first established in 1854, accepted

by Gray in 1855, with priority and dating corrected by Cabanis & Heine in

1860 and 1863.”

“Here is the crux of the problem: Gray considered them synonyms

(two names applied to the same group of species), but nothing can be firmly

inferred about whether he considered them “objective synonyms” (sharing a type

species) versus “subjective synonyms” (same taxonomic scope but different

type).

“The introduction is skimpy and doesn’t say whether the listed

types also apply to synonyms.

https://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/page/17136778#page/11/mode/1up

“If you see other cases in his lists, it is not clear that the

type species also corresponds to the synonyms. For example:

“Here, Motacilla

caerulea is the type

of Polioptila, as we all

know. Culicivora is included as a synonym of Polioptila,

as they were treated as synonyms by previous authorities. But the type species

of Culicivora was already clearly established by Swainson as C. stenura (= caudata, Tyrannidae). So, in this case, I

don’t think that Gray is establishing a new type species for Culicivora

(which would be against the rules and will have consequences for our current

usage).

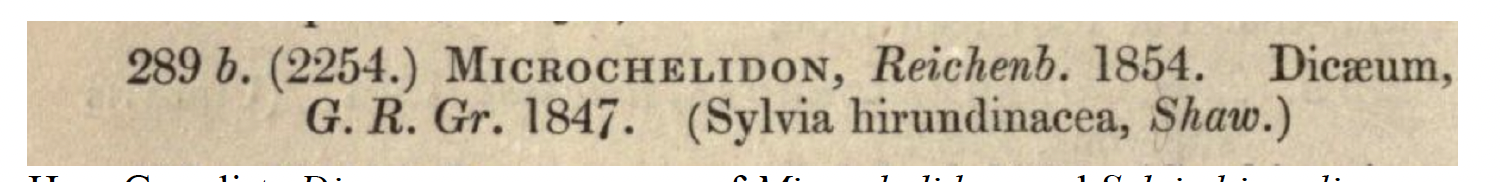

“Another case with a similar construction:

“Here Gray lists Dicaeum as a synonym of Microchelidon, and Sylvia hirundinacea as the type of Microchelidon. The type

of Dicaeum is D. cruentatus, not S. hirundinacea.

“In many other cases the type applies to both, but the majority

are cases of spelling variants, not true synonyms.

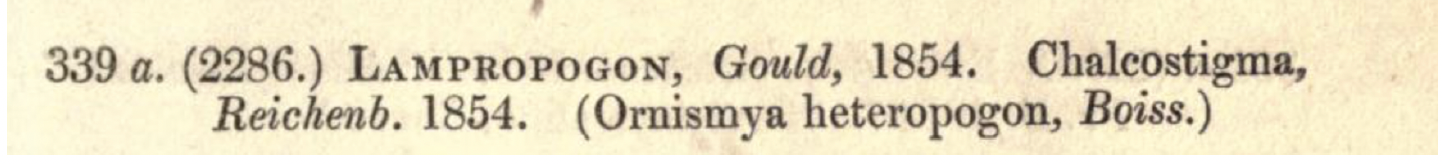

“However, there are some cases like this:

“In this case, Ornismya is indeed that type of both Lampropogon and Chalcostigma, and they are objective synonyms. But you cannot

infer that from Gray’s skimpy text. We know that by digging into the literature

and figuring out the type of each..

“Yet in other cases the type within parenthesis seem to apply only

to the synonym only!

“Therefore, Gray seems to be inconsistent about listing types. It

doesn’t seem that there is a clear methodology here.

“More importantly, the Code clearly indicates that type species

cannot be just inferred from context. If they are not fixed in the original

description (as in this case), they are to be established using the rules of

Art. 69 (https://www.iczn.org/the-code/the-code-online/)

“ICZN: Art. 69.1.1. In the absence of a prior type fixation for a

nominal genus or subgenus, an author is deemed to have designated one of the

originally included nominal species as type species, if he or she states (for

whatever reason, right or wrong) that it is the type or type species, or uses

an equivalent term, and if it is clear that that author accepts it as the type

species.”

“I’m not convinced that Gray’s list fulfills these requirements.

“Historical context is important, but it cannot be used in

substitution or contravention of Code rules. The Code is fairly explicit about

how historical information should be used (specific regulations for older names

versus newer names, etc.). Just because some authorities interpreted Gray’s

list as establishing type species is not enough.”

New Comments from Steve Gregory (voting for Bonaccorso): “Santiago

has admirably shown that the 'chief synonyma' in

Gray's 1855 Catalogue are far from consistent, representing, at best, Gray's

opinions about both objective and subjective synonyms, and that the types of

the senior synonym cannot be 'transferred' to any included junior synonym.

Frank Rheindt wrote "We can only honor and tolerate such pre-Code

practices where they have been explicit, such as Gray’s type designation for

Cyanomyia. What Bruce & Stiles ask us to do now is

to extend that tolerance to Uranomitra, even

though this genus-group taxon was never listed by number in Gray’s

catalogue" and "I wonder how Bruce & Stiles are so confident that

Gray didn’t list Uranomitra

as a subjective (rather than objective) synonym?"

We have maintained all along that the Code (Articles 67.5 and

69.1.1) requires that types be clearly and unambiguously stated, with Gray's synonyma demonstrably not the case. No one is doubting that

both Uranomitra

Reichenbach, 1854, and Coeruleomitra

Stiles & Bruce, 2021 are available. They both have

Trochilus franciae Bourcier & Mulsant, 1846, as

the type species. The former by subsequent designation by Elliot, 1879,

Smithson. Contrib. Knowl., 23, art. 5, p. 195.

Looking at this, Elliot clearly listed "Uranomitra Reich., Aufz. der Colib. (1853). p. 10.

Type T. franciæ.

Bourc." It should be noted that

Stiles & Bruce attempted to dismiss this as "a misunderstanding that

was not explained" but Article 69.1.1 is clear that "if he or she

states (for whatever reason, right or wrong) that it is the type or type

species, or uses an equivalent term, and if it is clear that that author

accepts it as type species."

“I agree with Frank that ‘works subsequent to Gray's Catalogue do

not salvage the case’. The Code must be applied at the point of establishment,

and aside from the provisions relating to subsequent designation, the opinions

and actions of others have no material bearing. Peters would have saved the

world from a heap of problems if he had decided to include full synonymies, as

far too many have assumed that those names he did list are the only ones

available to choose from.

“We should close by stating clearly that Uranomitra

Reichenbach, 1854, is the valid name for the taxon that includes

Trochilus franciae Bourcier

& Mulsant, 1846, the type species by subsequent designation, Elliot, 1879,

as having priority over Coeruleomitra

Stiles & Bruce, 2021, Article 23.1 (ICZN, 1999: 24).

“This is therefore a 'no' vote, as defined by the SACC proposal

924, on my part. Be that as it may, is it anyone else's feeling that this may

need pulling together as a paper?”

New comments from Pacheco: “I maintain the vote NO. I simply

agree with the last points added by Frank, Santiago and Steve. Despite the

historical context and the commendable work of Bruce & Stiles, the absence

of irrefutable indication of type-species of by Gray and the application of

art. 69 of the ICZN remain irreconcilable.”