Proposal (930) to South

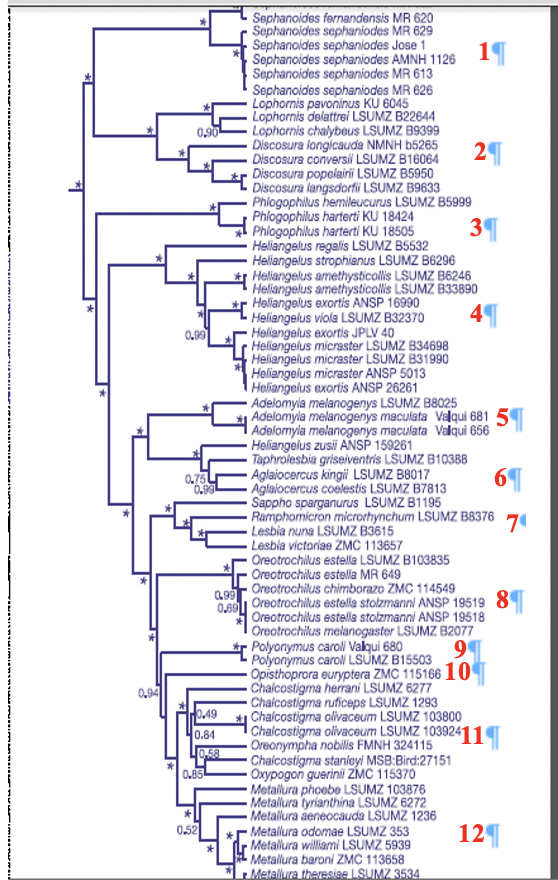

American Classification Committee

Revise generic limits

in the Lesbiini: A. Expand Oxypogon to include Oreonympha and Chalcostigma,

and B. Modify linear sequence

The comprehensive phylogeny of the Trochilidae

by McGuire et al. (2014) has generated major

revisions of generic limits in the family that have already been addressed by

SACC. We (mostly Gary) are in the

process of addressing a series of minor revisions with each tribe to bring the

SACC classification up to date.

This

proposal addresses one case within the Lesbiini: the possible extensive

paraphyly of Chalcostigma.

To

put the proposed change in context, an overview of the phylogeny with respect

to current generic limits is presented below.

When

more than one option exists, we usually emphasize branching order over branch

lengths, and in most cases prefer the option that least affects stability.

Clade 1. Includes only the

genus Sephanoides, which definitely represents a separate genus.

Clade 2. Includes two

monophyletic groups of similar age, Lophornis and Discosura, both

well characterized morphologically and entitled to generic status.

Clade 3. Includes only the

genus Phlogophilus, which definitely retains its generic status.

Clade 4. Includes only the

genus Heliangelus. The species regalis is a genetic outlier, with

a very distinct adult male plumage (although the female plumage is closer to

that of other Heliangelus. Two options exist: A. Separate regalis in

its own genus, for which a new name would be required; or B. retain it in Heliangelus,

recognizing the similarity of the female plumage to others of the genus. We

recommend this option, which also preserves stability.

Clade 5. Includes only the

genus Adelomyia, which retains its generic status; although some recent

studies suggest that the several subspecies include distinctive lineages,

evidence to date appears insufficient to justify recognition of any of these as

species.

Clade 6. Includes Heliangelus

zusii, Taphrolesbia and Aglaiocercus. Heliangelus zusii is now thought

to be a hybrid, and hence may be excluded from further consideration. The

branch lengths separating Taphrolesbia and Aglaiocercus are

rather short; hence, two options exist: A. lump both into a single genus (in

which case, Taphrolesbia (Simon, 1918) has priority over Aglaiocercus

(Zimmer, 1930), or B. maintain both as separate genera. The two are quite

distinctive in plumage, and this option favors stability; we prefer this

option.

Clade 7. Includes the genera Sappho,

Ramphomicron, and Lesbia. The three genera separate in this

order by two rather small steps. Here also there appear two alternatives: A.

lump all three into a single genus for which Lesbia (Lesson, 1833) takes

priority over Sappho (Reichenbach, 1849) and Ramphomicron (Bonaparte,

1850). And B. maintain three separate genera. All three are distinctive

morphologically, and this option maintains stability; hence, we favor it.

Clade 8. This includes only Oreotrochilus,

which clearly should retain its generic status.

Clade 9. This includes only Polyonymus,

on a long branch: definitely a monotypic genus.

Clade 10. Another

morphologically distinctive species with no close relatives: Opisthoprora also

merits generic status.

Clade

11.

Includes members of three genera: Chalcostigma, Oreonympha, and Oxypogon.

The very short branches between them indicate that their speciation was rapid;

a complication is that as it stands, Chalcostigma is likely paraphyletic

with respect to the other two genera, but note the low support values for the

topology. We therefore consider a novel option: include all members of this

clade in a single genus, for which Oxypogon Gould, 1848, takes priority

over Chalcostigma Reichenbach, 1854, and Oreonympha Gould, 1869.

It is noteworthy that this is the first time that these three genera have been

treated together, without other intervening genera (usually Metallura)

in the linear sequence. The support for

the node that unites them as a group is very strong. An expanded Oxypogon would

include all of the species in which the gorget is restricted laterally to form

a narrow, multi-colored “beard” (see photos below), which could be considered a

synapomorphy; also, Oreonympha and Oxypogon s.s. (including the

three species we now recognize) share conspicuous white in the tail. All are species of high elevation cloud-forest,

elfin forest, and páramo.

Clade 12. Includes only the

genus Metallura. Because the species are mostly separated in a sequence

of moderate to small steps, we see no reason to attempt to subdivide the genus,

which is morphologically coherent, and recommend continuing to consider all

species as congeneric, which also maintains stability.

A.

Expand Oxypogon to include Oreonympha and Chalcostigma: As noted above under

Clade 11, we think this merger warrants consideration because there really

isn’t any evidence that Chalcostigma is monophyletic. A practical problem is that McGuire et al.

(2014) did not have access to tissue of the type species (heteropogon) for

Chalcostigma Reichenbach, 1854; therefore, even the assignment of

species to Chalcostigma s.s. would depend on assumptions that cannot be

supported by genetic data. Traditional Chalcostigma

is fairly heterogeneous, with C. ruficeps decidedly smaller than the

others, and the female is phenotypically more similar to Metallura

tyrianthina than to its current congeners; it also occurs at lower

elevations. One could make the case for

splitting Chalcostigma at least 4 ways based on the topology above, at

least 3 of which would be monotypic: (1) herrani, (2) ruficeps

(sister relationship to olivaceum has weak support); (3) olivaceum;

and (4) stanleyi, and hope that type species heteropogon is

sister to one of these. This would allow

maintaining Oxypogon as a tight genus of four allospecies (see SACC 609) and Oreonympha

as a distinctive monotypic genus.

However, the branch lengths among these are more similar to those among

many congeners within other genera in the Lesbiini.

Photos

of males from LSUMNS specimens:

A YES vote would have the added benefit of

highlighting the close relationship among all these rather phenotypically

divergent but similar species and suggests that there is something about this

lineage that allows rapid plumage diversification, perhaps facilitated by their

isolation and likely very small populations during the height of interglacial

warm cycles. An expanded Oxypogon

would be certainly monophyletic. A NO

vote would maintain a likely paraphyletic Chalcostigma but would

emphasize the need for better-supported typology and possible inclusion of the

type species of Chalcostigma.

B.

Modify linear sequence. If we do not

change generic limits, a change in linear sequence is required. Our current sequence is: Chalcostigma,

Oxypogon, Oreonympha. Maintaining

those three genera as is would require an inversion of that sequence under

standard sequencing conventions, with most diverse genera listed successively, e.g.,

Oreonympha, Oxypogon, Chalcostigma.

Gary Stiles and Van

Remsen, November 2021

Comments from Areta:

“A. NO. I feel

uncomfortable making this move, given the low support of several branches and

the lack of samples from the type species of Chalcostigma. In the long run, this might be a reasonable generic

arrangement, but I prefer to wait for more solid data before making changes.

“B. YES, modify the sequence to match the richness of each group.”

Comments from Robbins:

“A. YES for subsuming all of the former Chalcostigma taxa and Oreonympha

into Oxypogon given the node that unites this group is strongly

supported and that priority has been clearly established.

“B. YES, for

changing the linear sequence.”

Comments from Lane:

“A. YES. I

don't think it's likely that C. heteropogon will be outside this clade,

so I think it is fairly safe to go ahead with the merging of genera into Oxypogon

now.

“B. YES to

reordering the members of the larger clade.”

Comments from Pacheco:

“A – YES.

As the node that unites this group shows strong support it is acceptable to

combine these 3 genera to expand Oxypogon.

“B – YES. The change in the linear sequence must be made.”

Comments from Bonaccorso:

“A. NO. Many of McGuire et al.´s relationships are driven by

mitochondrial DNA and in this case many branches are short. Because this is not

a “life or death” situation, I think it is better to wait for more data and

inclusion of C. heteropogon in the analysis. In the meantime, we can maintain

stability for a while longer.”

“B. YES, but just to reflect the phylogenetic sequence.”

Comments from Claramunt:

“A. NO. The three genera are so distinctive phenotypically that I

think we should wait for stronger evidence before making any change in this

group.

“B. NO. For the same reason.”

Comments from Zimmer: A.“YES for subsuming all Chalcostigma taxa and Oreonympha into a single, expanded Oxypogon, given that the node uniting

this group is strongly supported, and that Oxypogon

has priority. Normally, I’m a proponent

of smaller, more internally cohesive genera, particularly for such

morphologically distinct groups such as Oxypogon

sensu stricto. However, the apparent paraphyly of the

current arrangement bothers me (even though the support levels for the topology

are not particularly impressive), and a merger into an expanded Oxypogon would seem to result in an

unquestionably monophyletic group. I’m

also intrigued by the potential for uniting all of these proportionately

short-billed, long-tailed, high-elevation species with narrow, multicolored

“beards” into a single group, as mentioned in the proposal. As Dan has opined, I don’t see C. heteropogon falling outside of the

clade, so, although it would be preferable for the type species of Chalcostigma to have been sampled by

McGuire et al. (2014), its absence from their phylogeny shouldn’t be an

impediment to making the proposed generic merger in my opinion. The alternatives would be A) Maintain a

status quo with three seemingly paraphyletic genera; or B) maintain the

stability of Oxypogon and Oreonympha, while splitting Chalcostigma into as many as four genera

(at least 3 of which would be monotypic), and still not knowing for certain how

any of them relate to heteropogon. Despite the phenotypic distinctions between

the three genera as currently recognized, I think there are more phenotypic,

ecological, and distributional characters that unite Chalcostigma, Oxypogon and Oreonympha

than there are differences within currently recognized Chalcostigma. B. YES to changing the linear sequence

of the expanded clade.

Comments from Remsen:

NO. Based on Elisa and Santiago’s comments on the genetic data, and

because the genera as currently defined seem to be mostly cohesive units, I’m

backing away from my recommendation in the proposal. I do think it would be OK to change the

linear sequence because the node that unites the three genera looks solid, and

so rearrangement within that group should follow sequencing conventions; the

support for altering generic limits is weak, but the support for them as a

group is strong … at least as far as that data-set goes, and those are the best

data we have so far.”

Additional

comments from Stiles:

“I very much doubt that C. heteropogon

would fall outside Chalcostigma - but surely there should be tissue

samples in Colombia … and the node connecting the 3 genera seems well

supported, such that to avoid paraphyly of Chalcostigma and place all 3

in Oxypogon still seems to me to be the best option.”

Comments

from Jaramillo:

“A. YES – I may be in the minority, but these hummingbirds are not all that

phenotypically diverse. They are uniquely “bearded” in their gorget shape. They

are also relatively short billed, and also somewhat uniquely long-tailed. The

tails are sometimes broad and have more area than the wings, not the norm in

most hummingbirds. I think this group looks pretty tight as a single genus. YES

– if necessary.”