Proposal (931) to South

American Classification Committee

Recognize Haematopus bachmani (Black

Oystercatcher) as a subspecies of H. ater

(Blackish Oystercatcher)

Note from Remsen: This is a proposal

submitted to NACC that Terry Chesser asked me to submit here also to SACC to

coordinate our decisions.

Effect on

SACC:

This would lump the Black Oystercatcher (Haematopus bachmani) of Pacific-coast

North America with the Blackish Oystercatcher (H. ater) of South America, considering the former as a subspecies

of the latter, and thus would expand dramatically the range of the SACC

species.

Background:

We are revisiting this species limits issue in

association with the effort to harmonize world lists, and treating H. bachmani as a separate species is a

point of disagreement.

Oystercatcher taxonomy has been an ongoing

challenge because members of the family are morphologically quite conservative.

The two general plumage types, black and pied, tend to correspond to rocky

versus soft shoreline specialization, respectively (Jehl 1985, Hockey 1996).

H.

bachmani

has been recognized as a species by the Check-list

in every edition since the first. The ranges of H. bachmani and H. ater

are entirely allopatric, so the most appropriate way to determine species

limits in this case is to infer them using the classic yardstick comparative

method (although it has been applied infrequently and not with the depth one

might hope for today; Murphy 1925, del Hoyo and Collar 2014). Both taxa occur

in sympatry with the more widespread H.

palliatus (American Oystercatcher), and both hybridize with this pied form

(ater and bachmani are of course of the black plumage type, as their English

names indicate; Jehl 1985, Hockey 1996).

The taxonomic notes provided in the 6th

and 7th editions (AOU 1983, 1998) mentioned that some authors had

considered H. bachmani and H. palliatus (American Oystercatcher) to

be conspecific; they have a hybrid zone of ~480 km in width in Baja California

(Jehl 1985). It is not apparent whether the relationship between bachmani and ater has been evaluated by NACC before.

Murphy (1925:13-15) elaborated on the

differences and similarities between ater

and bachmani thus: For bachmani: “Juvenal birds closely

resemble the young of H. ater, the

feathers of the upper surface, breast, and flanks being edged with pale tawny

brown. It is interesting that the down of chicks of this species is much darker

than that of H. ater or of any other

American form.” And for ater:

“Superficially resembling H. bachmani,

H. ater is widely separated from all

other oyster-catchers in the form of the bill, the excessive compression of

which approaches that of Rynchops.

The distinctive character of the bill is apparent even in chicks taken from the

egg. Color differences between H. ater

and H. bachmani are much greater

among downy young than among adults. The young of ater are relatively pale, only slightly darker, indeed, than those

of H. palliatus, which they much

resemble. The white area is confined to the breast, instead of covering the

belly and flanks as in palliatus, but

it is far more extensive than in bachmani.”

As Jehl (1985) remarked, although AOU (1983)

and Murphy (1925) recognized H. bachmani

and palliatus as separate species,

most other authors did not at that time. For example, H. bachmani and H. palliatus

have been considered conspecific by Peters (1934), Friedmann et al. (1950), and

Mayr and Short (1970)—all of these considered bachmani and palliatus as

subspecies of H. ostralegus, the

Eurasian Oystercatcher. This situation has changed, however, and most

authorities now recognize palliatus

and bachmani as separate species

(checking via Avibase; https://avibase.bsc-eoc.org). Jehl’s (1985) work

appears to have been effective on this issue.

Peters (1934), while lumping both palliatus and bachmani in ostralegus,

considered H. ater to be a separate

species. Although this work does not provide any reasoning behind its taxonomic

decisions (long a sore point), this could have been based on Murphy (1925) or

been simply inertia; as Hockey (1996) related, in the genus in general allopatric

black forms have been considered species, whereas pied forms are often

considered subspecies.

In his study of the hybrid zone between bachmani and palliatus, Jehl (1985) found assortative mating, a stable (though

480-km wide) hybrid zone (after late-19th and early-20th c.

disruption), and inferred selection against hybrids, leading him to conclude

that the two are valid species. He surmised that the primary mechanism of

reproductive isolation was likely postzygotic, focusing especially on predation

on chicks of mixed pairs in which some would have plumage coloration

inappropriate for their beach color, i.e., through loss of crypsis. Given the

high rates of chick predation in some species (60-85%; Hockey 1996), this seems

plausible.

H. ater also hybridizes with H. palliatus, in Argentina (Jehl 1978).

Jehl (1978) described a single hybrid specimen between ater and leucopodus (the

Magellanic Oystercatcher, also a pied form) that he took in Santa Cruz

Province, Argentina. This latter hybridization event (ater-leucopodus) is uncommon compared to ater-palliatus crossings, which he noted occur in this area of

overlap “with appreciable frequency” (Jehl 1978:346). Both the bachmani-palliatus and ater-palliatus hybrid zones should be

revisited with population genetics studies to determine the degrees of

introgression (given clearly incomplete isolating mechanisms), but I do not

know whether such work is occurring.

New

Information

There is remarkably little modern work

available on Haematopus systematics

or species limits. This is an area ripe for study.

Using mtDNA (COI) barcoding, Hebert et al.

(2004) found that the difference between H.

palliatus and H. bachmani was

remarkably low compared with other North American bird species-level

differences, and they considered that this was consistent with treating them as

a single species.

Senfeld et al. (2020) also examined mtDNA (2835

bp) and found palliatus, ater, and bachmani to be very closely related, with bachmani perhaps being sister to the other two. This clade is quite

distinct from H. leucopodus, the

Magellanic Oystercatcher, another pied form as noted above.

del Hoyo and Collar (2014) lumped bachmani and ater, stating that “Race [sic] bachmani

has normally been considered a separate species, but the two are almost

identical in plumage and voice, apparently differing only in greater depth of

bill of nominate ater. Two subspecies

recognized.” (p. 420). (It is worth contrasting this brief emphasis of

similarities with Murphy’s [1925] emphases on differences quoted above.)

Careful analysis of vocalizations is needed.

Subjectively, listening to some of the recordings on xeno-canto (https://xeno-canto.org) reminds me of the

mtDNA relationships: bachmani, ater, and palliatus are similar; leucopodus

is different. It is perhaps no accident that these similarities and differences

are reflected in the rates of hybridization where the taxa overlap. Future work

is also needed to rigorously quantify morphological similarities and

differences. Murphy’s (1925) evaluations show some disagreement with del Hoyo

and Collar’s (2014) conclusions.

With neither appreciable song nor plumage

differences between ater and bachmani, neither assortative mating nor

the putative postzygotic isolating mechanism of strong plumage color selection

favored by Jehl (1985) would likely be very effective in preventing substantial

hybridization (especially given considerable levels of crossing of both with palliatus). I realize that such

conjectures are rather unsatisfactory, but that is one of the acknowledged

weaknesses of the biological species concept when asking whether allopatric

forms are “different enough” to warrant recognition as full species.

Two broader issues have some relevance when

evaluating this and other cases in which allopatry and the Tobias et al. (2010)

criteria are in play. Although many do not like the Tobias et al. (2010)

criteria, the accumulation of subsequent, independent case studies indicate

that the initial use of these criteria has proven much more often right than

wrong in determining species limits (Tobias et al. 2021; although see Rheindt

and Ng 2021 who came to a different conclusion using a different approach). In

addition, across Aves we are likely over-splitting allopatric taxa at the

species level (see Hudson and Price 2014). These are generalities, probably

both true. That said, each case should be rigorously examined.

Taxonomy

and nomenclature:

H. ater (Vieillot and Oudart

1825; Galerie Oiseaux, II, p. 88, I,

P1. ccxxx) has priority over H. bachmani

(Audubon 1838; Birds of America,

folio edit., IV, P1. ccccxxvII, fig. 1). See Murphy (1925) for discussion of

the history of ater and its priority

for that taxon. Thus, if this proposal is approved, H. bachmani would become H.

ater bachmani. Murphy’s (1925) study of the two supports considering bachmani a valid subspecies if lumped

with ater.

Recommendation:

Based on current evidence, particularly the

strikingly different phenotypes of both bachmani

and ater from palliatus and the noteworthy levels of hybridization with that pied

form, these taxa should be considered a single biological species with two

allopatric subspecies-level populations. I find especially compelling that the

strikingly different phenotypes of bachmani

and palliatus appear to be barely

limiting hybridization in a region of overlap to a level that only some

authorities (us included) consider to be low enough to be full biological

species. Given the remarkably close mtDNA relationships among palliatus, bachmani, and ater, it

seems likely that the phenotypic similarities between the latter allopatric

pair (including vocalizations) would be insufficient to preclude more extensive

hybridization if the two were to come into contact.

The vote is in two parts.

A. Recognize H. bachmani as a subspecies of H.

ater.

If A is approved, then B: Apply

the English name Blackish Oystercatcher to both taxa (as HBW-BirdLife already

does).

Literature

Cited

American

Ornithologists’ Union (AOU) (1983). Check-list

of North American Birds, Sixth edition. American Ornithologists’ Union,

Lawrence, Kansas.

American

Ornithologists’ Union (AOU) (1998). Check-list

of North American Birds, Seventh edition. American Ornithologists’ Union,

Washington, D. C.

del Hoyo,

J., and N. J. Collar. 2014. HBW and BirdLife

International Illustrated Checklist of the Birds of the World. Volume 1:

Non-passerines. Lynx Edicions, Barcelona.

Friedmann,

H., L. Griscom, and R. T. Moore. 1950. Distributional

Check-list of the Birds of Mexico, Part 1. Pacific Coast Avifauna 29.

Hebert,

P.D.N., M. Y. Stoeckle, T. S. Zemlak, and C. M. Francis. 2004. Identification

of birds through DNA barcodes. PLoS Biology. 2:e312.

Hockey, P.

A. R. 1996. Family Haematopodidae (oystercatchers). Pp. 308-325 in Handbook

of the Birds of the World, Vol. 3 (del Hoyo, J., t al., eds.). Lynx

Edicions, Barcelona.

Hudson, E.

J., and T. D. Price. 2014. Pervasive reinforcement and the role of sexual

selection in biological speciation. Journal of Heredity 105:821-833.

Jehl, J.

R., Jr. 1978. A new hybrid oystercatcher from South America, Haematopus leucopodus × H. ater. Condor 80:344-346.

Jehl, J.

R., Jr. 1985. Hybridization and evolution of oystercatchers on the Pacific

coast of Baja California. Ornithological Monographs 36:484-504.

Mayr, E.,

and L. L. Short. 1970. Species taxa of North American birds. Publications of

the Nuttall Ornithological Club 9.

Murphy, R.

C. 1925. Notes on certain species and races of oyster-catchers. American Museum

Novitates 194:1-15.

Peters. J.

L. 1934. Check-list of Birds of the World,

Vol. II. Cambridge, Harvard

University Press.

Rheindt, F.

E., and E. Y. X. Ng. 2021. Avian taxonomy in turmoil: The 7-point rule is

poorly reproducible and may overlook substantial cryptic diversity. Ornithology

138: 1–11.

Senfeld,

T., T. J. Shannon, H. van Grouw, D. M. Paijmans, E. S. Tavares, A. J. Baker, A.

C. Lees, and J. M. Collinson. 2020. Taxonomic status of the extinct Canary

Islands Oystercatcher Haematopus

meadewaldoi. Ibis 162:1068-1074. https://doi.org/10.1111/ibi.12778

Tobias,

J.A., N. Seddon, C. N. Spottiswoode, J. D. Pilgrim, L. D. C. Fishpool, and N.

J. Collar. 2010. Quantitative criteria for species delimitation. Ibis

152:724–746.

Tobias, J.

A., P. F. Donald, R. W. Martin, S. H. M. Butchart, and N. J. Collar. 2021.

Performance of a points-based scoring system for assessing species limits in

birds. Ornithology 138: ukab016

Kevin Winker, February

2022

Comments

from Lane:

“NO. Clearly

there is little room for wide variation within the plumages of Haematopus,

with blackish and pied varieties scattered across the coastlines of the world.

They also seem to show some taxonomic constraint in voice, particularly to the

untrained human ear, but in the present case, I would argue that there are

indeed some clear character differences between ater and bachmani.

The former's excitement duet series begins with a rising rapid chatter (not

typically initiated with long notes) that culminates with falling

multi-syllabic notes that look like "M"s or triple-peaked notes (https://macaulaylibrary.org/asset/203976141). The

single note call is in the .11 to .25 second range. By comparison, H. bachmani

enters its excitement duet series with long notes descending into a rapid

chatter that then rises back into a series of couplets that are separate notes

(not multisyllabic notes) (https://macaulaylibrary.org/asset/137867). The

latter is far more like the excitement duet chatter of H. palliatus,

both North and South American forms, by the way (https://macaulaylibrary.org/asset/63003121, https://macaulaylibrary.org/asset/310733941). The

single note call of H. bachmani is in the .29 to .35 second

range. For comparison, H. palliatus has single note calls in the

.28 to .39 second range. [I confess these are based on only a couple recordings

for each species, but eyeballing several recordings of each vocalization type I

think the patterns are real]. So, yes, I would say there are distinct vocal

characters separating H. bachmani and H. ater,

contra what Winker suggests in the proposal.

“The broad overlap of H. ater and H. palliatus

in South America (from Ecuador south to Tierra del Fuego and then north to

central Argentina) with minimal hybridization (I am unaware of any in Peru,

where both occur along the length of the coast), quite unlike the broad hybrid

zone between H. bachmani and H. palliatus (in the

relatively limited overlap they share in southern California and Baja),

suggests that these vocalization differences may be instrumental in maintaining

segregation between H. ater and H. palliatus

whereas the more similar vocalizations between H. bachmani and H.

palliatus could be a reason for the more readily interbreeding of the

two in Baja. Thus, it could be inferred that voice differences between H.

bachmani and H. ater could be a deterrent to interbreeding

between them should they meet hypothetically. I think it is clear that the

"lumperama" days of the last century glossed over some rather

significant characters that differentiated the pied Haematopus (e.g.,

putting H. palliatus or H. finschii into H. ostralegus

simply for superficial plumage similarity and allopatry) and that we should be

wary of doing the same in this century simply because H. ater and

H. bachmani look similar! I vote NO.”

Comments

from Jaramillo:

“NO. I am confused by this proposal. There are multiple elements here that are

not being given due weight in my opinion, and the data is summarized in a way

that suggests that to lump the two black oystercatchers in the New World is

somehow logical. Here are my issues with the proposal.

1)

DNA

– Hebert et al. 2004

https://journals.plos.org/plosbiology/article/file?id=10.1371/journal.pbio.0020312&type=printable

What

can we take away from this paper specifically related to Oystercatchers? I

think three individuals were sampled if I understand correctly. Which

populations of American Oystercatcher? One or multiple? Perhaps we have a hint

that the lineages are recent, but which lineages exactly? I don’t know that we

can deduce anything relating to the question of how many species are involved

from this paper.

2)

Hybridization

– Two hybrid areas are noted. The dynamics of Black and American hybrids in

Mexico are well studied, although the work is now old. A mechanism is given as

to potential selection against hybrid young, as stated in the proposal. But

note that the difference in habitat between Black vs American (Rock vs Sand)

alone, assuming habitat choice is not learned, would be a barrier to gene flow.

The Argentine area of hybrids between American and Blackish is noted, although

this is not well known, and may not be a true hybrid zone as opposed to an area

where hybrids are sometimes noted? I am not clear.

3)

The

thought that a) Black and American show low genetic divergence and b) American

hybridizes with Black at some points, and Blackish at other areas is implied to

mean that gene flow is relatively unimpeded. Maybe? Maybe not. But then I don’t

understand the conclusion to lump Black and Blackish. Shouldn’t the conclusion

be to lump American and Black? And perhaps ask for more work on Blackish to

decide what to do in the future with that? But see below.

4)

NOW

– what is missing here? Well Blackish (ater) and American are sympatric

for thousands of km in Chile and Peru. There are no hybrids that I know of

there. They act like perfectly fine biological species, and you can see them

adjacent to each other, but in different habitat, commonly throughout this

range.

5)

The

proposal mentions that vocalizations seem to be similar between all three taxa,

and are perhaps likely not important as a barrier to gene flow (see final

sentence of recommendation in the proposal). BUT oystercatchers all sort of

sound similar, some are much more clearly different. But they have a whistled

flight call, shorter flight calls, and the duet of quickly repeated notes.

These demand much more study. Because “subjectively” they are similar, and if

you listen to American vs Blackish (ater) you would conclude this to be

the case, yet these two species are sympatric and share a range of thousands of

km. So, something is keeping them apart. Perhaps it is as simple as habitat? I

don’t know. But something is keeping them apart, we cannot discount that

because voice is similar subjectively that it is not doing something, or

perhaps we have not gotten at the difference in that voice.

6)

There

is an assumption that American itself is one thing. However, when I visit Chile

and then I go to Uruguay, the voices I hear are different. I looked at the East

Coast US birds on xeno-canto as well and those sound more like the Uruguay

birds to me as well. It is subtle and this requires more work. But perhaps it

is a mistake to treat American Oystercatchers as all the same thing,

particularly given that they have this linear range, around the perimeter of

the continent, and that Pacific birds are likely not sharing genes with

Atlantic birds at all or have done so less than Argentine American (palliatus)

does with Blackish (ater)! This all needs more work.

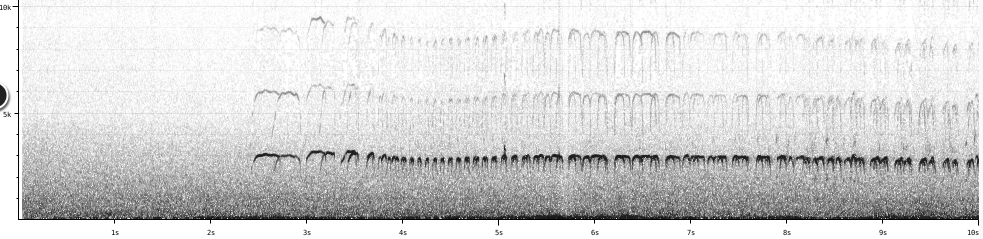

Have

a listen – Chilean birds are lower pitched, less strident. Their crescendo

calls do not tend to start with longer, louder whistles. How quickly these

vocalizations are given varies depending on the excitement state of the birds,

but Atlantic birds sound higher pitched, more strident, often with longer

whistled notes at the start. Other oystercatcher species vary in the structure

of the preliminary notes before the duet, so this might be significant. Note

that duets sometimes sound syncopated, other times they do not. The syncopated,

“tic-toc” type situation is more common in the Pacific. Chilean birds are

slower, US and Uruguayan birds (Atlantic) appear to deliver the duet more

quickly. Obviously more study is needed.

But

this does call into question how you evaluate hybridization of ater

(Blackish) with American, as it only happens in the Atlantic, and not the

Pacific. Why?

Chile

US

Uruguay

7)

Voice

of Blackish (ater) and Black (bachmani) differ. I live in the

range of bachmani and hear them on a weekly basis. When I visit Chile, ater

does not immediately register to me. It is subtle. Weirdly enough to me

Americans sound more like bachmani. The voice I am particularly thinking

about is the flight call, which is a whistle. Here at home bachmani

gives this melancholy and relatively long whistle with an inverted U shape on a

spectrogram. Meanwhile ater is much quicker, without thorough analysis I

would say that ater has a call that is often half the length of the

similar call of bachmani. There is variation. however! To my ear the

difference is enough that I recognize a Blackish (ater) as an

oystercatcher, but Black (bachmani) is not what come to my head when I

hear them. Again, the duet voices sound similar, but I bet they are not if

someone was to analyze clearly. But given that flight calls differ between

these two species, I think we might find some differences in the duet call as

well. Would this preclude hybridization? I don’t know, but how ater

interacts with Pacific palliatus (hybrid zone where two ranges meet), is

entirely different than how bachmani interacts with Pacific palliatus

(no hybridization). That alone suggests the two black species should not be

lumped. It is also making an assumption that all Pacific palliatus are

the same lineage, I do not know if that is the case.

Flight

calls ater – shorter more abrupt.

Flight

calls bachmani – longer, more melancholy.

8)

Finally,

morphology. We are overlooking this bill of ater, it is a monster of a

bill. The expansion of the mandible is such that it can resemble a skimmer!

This bill is adapted to entirely different creatures than the smaller bill of bachmani.

Sure, a bill shape might not preclude gene flow if the two came together. But,

assuming a largely genetic component to this particular bill shape, hybrids if

they happened, well they would neither be expected to be able to handle the

mollusks of Pacific South America, or Pacific North America. That is to say,

that this is not just a slightly large bill, it is an entirely different bill

shape. BTW, I think the same of Ringed Kingfishers in the Temperate zone and

the Tropical zone, they are so different in bill shape that I bet that hybrids

would not do well. But that is another story.

9)

To

me, much more work is needed. There are definitely some young lineages here, an

effect of habitat and ecological divergence, and perhaps an over emphasis on

lumping due to similar plumage of the two black species. I would not be

surprised if they are both offshoots of the American clade that may look

similar due to their habitat, but they may each be more closely related to one

of the American populations than they are to each other. But the fact that in

the Pacific of South America Blackish (ater) is sympatric with one form

of American, well that is enough for me to say, keep them all separate. And

that more work should be done to understand the dynamics within palliatus,

let alone how it relates to the two black species.”

Comments

from Peter Boesman: “Notes on the vocalizations of Black

Oystercatcher Haematopus bachmani and Blackish Oystercatcher Haematopus

ater:

“I

compared the sonograms of the Haematopus species, and most look very

much the same. Only in some cases of largely sympatric breeding areas of two

species of the genus, there seems to be some clear vocal differentiation, e.g.,”

Haematopus

ater vs. H. leucopodus: the latter has mainly

high-pitched squeaky notes in its vocabulary

Haematopus

finschi vs. H. unicolor: the latter has some more nasal

notes in its vocabulary

“In the specific case of Haematopus ater and H.

bachmani I think however I have found one difference! In the former

the long piping trill typically uttered during display or interaction

apparently always starts at the lowest frequency after which it rises in pitch

for a while to remain stable afterwards. In the latter it typically starts at a

high pitch after which it drops and rises a bit to remain stable afterwards.

Examples:

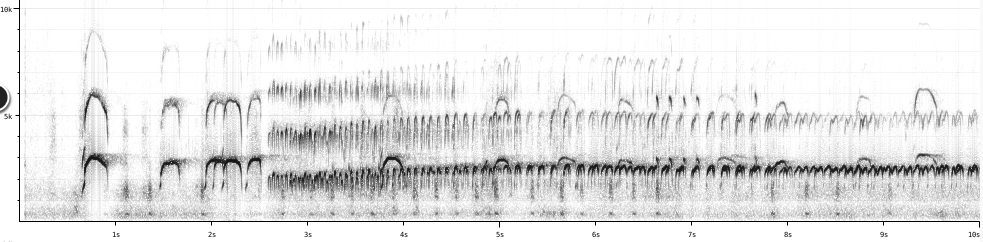

H.

ater (XC188260)

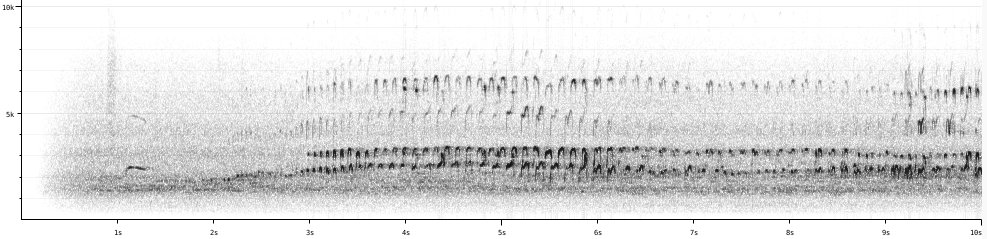

H.

bachmani

“There

aren’t that many recordings in which the full series is recorded from the very

start, however:

H.

ater

XC:

4 recordings, all have initial rise

ML:

2 recordings, all have initial rise

H.

bachmani

XC:

7 recordings, all showing the initial drop and rise in pitch

ML:

I didn’t listen to all 226 recordings but of the 7 I found having the piping

trill, all showed the initial drop and rise.

“Whether this is an important difference is hard to tell

but given the vocal variation in the genus is very limited, and given it is a

vocalisation used during display and interaction, it may well be considered

important. If it has to be scored for Tobias, one could define the parameter

initial drop or rise in pitch, which would give a score of about 3.

“A

possible second difference is that H. ater starts the

trill with very short notes which gradually increase in duration, whereas bachmani

has initial longer notes which reduce in duration during the drop in

frequency. I said ‘possible’ because one can’t be sure always if the initial

longer notes are from a second bird or not, but it would seem this feature

holds quite well, in which case it could also be given a score of 2-3.”

Comments from Remsen: “NO. The points made

by Dan, Alvaro, and Peter all strongly indicate not only that more work is

needed but also that bachmani and ater are unlikely to be sister

taxa, as suggested even by the weak genetic data in Senfeld

et al. It would seem to me that the

necessary first step in treating bachmani and ater as conspecific

would be to show that they are more closely related than either is to palliatus,

using more than just mtDNA and with broad geographic sampling. Until that necessary condition is met, I don’t

see any point in changing current species limits.”

Comments

from Robbins:

“NO for treating Haematopus bachmani as a

subspecies of H. ater for reasons detailed by all who have commented on

this proposal (as of 2 February 2022). Clearly, more study is needed before

making any taxonomic changes.”

Comments

from Areta:

“NO to H. ater bachmani. Although

there is clearly fertile ground for research, current vocal, plumage, and

morphological differences argue against the lump (thanks Alvaro, Dan, and Peter

for insight into some of these aspects).

“Phylogenetic

information (mostly Senfeld et al. 2019) and data on

hybrids also indicate that considering this case without including H. palliatus in the taxonomic debate is

futile. It is also the case that Murphy (1925:5) reported on the long wings and

large feet of H. ater in comparison to other Haematopus,

especially bachmani: "Of the native American species of Haematopus (H. ostralegus

being excluded) ater has by far the

longest wings and the largest feet, being in these respects at great variance

with the other black oyster-catcher, H.

bachmani."

“Regarding

the Pacific vs. Atlantic forms that Alvaro has mentioned, Murphy (1925: 4)

reads: "From still another geographic placement,

it is noteworthy that the Pacific races of ostralegus

and palliatus (e.g., longirostris, frazari, galapagensis, pitanay) have unmarked primary

quills, while the Atlantic races of both these species (e.g., H. ostralegus ostralegus,

H. palliatus paliatus,

H. p.prati,

H. p. durnfordi)

all share in greater or less degree the peculiar pattern. The rule breaks down

only near Panama, where the West Indian maritime avifauna has so generally

crossed over to the Pacific side". It is clear that

unless H. palliatus is studied at

length and across geography, we won´t have a clear picture of what to do with H. bachmani.

“I

see nothing in the proposal to change the status

quo of recognizing H. bachmani as

separate from H. ater.”

Comments from Pacheco: “NO. Given the informative

considerations made by Dan, Alvaro, and Peter, it is unsuitable to accept the

downgrade of Haematopus bachmani to subspecies.”

Comments

from Claramunt:

“NO. Similarity has never been a good guide for lumping forms into the same

species, and in this case there are clear morphological (bill shape is

diagnostic) and plumage (in juveniles, as pointed out by Murphy 1925)

differences.”

Comments from Bonaccorso: “NO. I think Alvaro´s detailed

reasoning is quite convincing. I vote no until more data and detailed analyses

are presented.”

Comments from Zimmer: “NO, for all of the reasons

nicely summarized by Dan, Alvaro, Peter, and others. I would add that the difference in plumage

ontogeny between ater and bachmani strike me as indicators of

distinctiveness too – juveniles of the two taxa are nearly identical in plumage,

whereas downy chicks differ significantly in color (and the differences in bill

morphology are also already apparent in downy chicks). As others have already elaborated, I think it

is dangerous to include alleged vocal similarity as a rationale for lumping

taxa, in the absence of any kind of quantitative analysis, and based solely

upon a gross qualitative comparison of how these things sound to the human

ear. And, as pointed out by Van and

others, any reevaluation of species limits as regards ater and bachmani, really

needs to include a proper analysis of the relationships of each of those taxa

to palliatus, and with broad

geographic sampling throughout the rather extensive ranges of all three species.”

Comments

from Stiles:

“NO - multiple lines of evidence clearly indicates

that lumping bachmani into ater is not a good option.”