Proposal (935) to South

American Classification Committee

Add Streptopelia decaocto (Eurasian Collared-Dove)

to main list

Effect on South

American CL:

This would transfer a species from the Hypothetical List to the Main List as

introduced species.

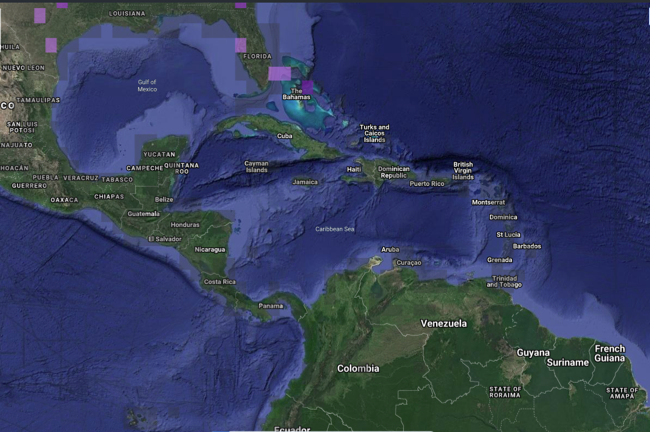

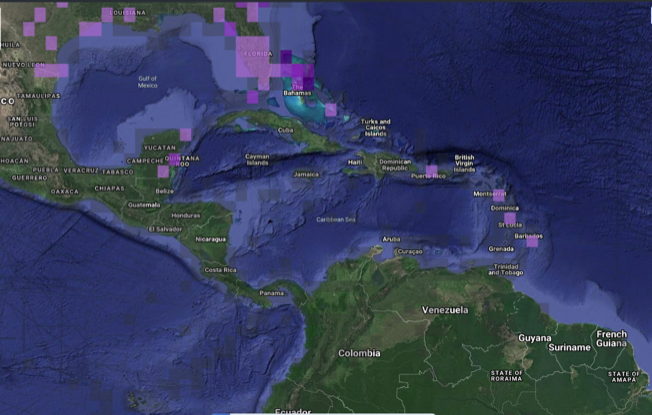

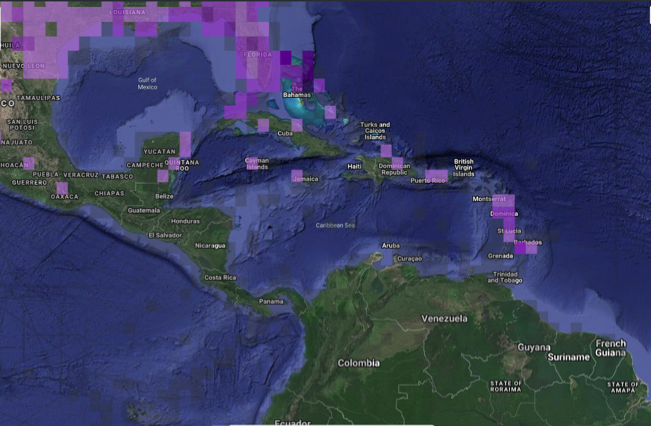

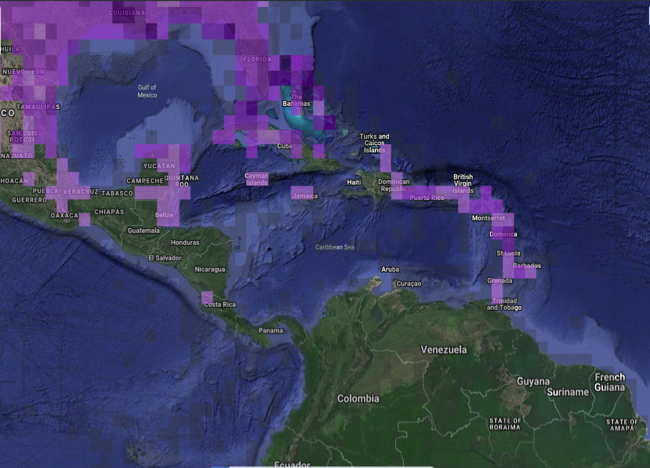

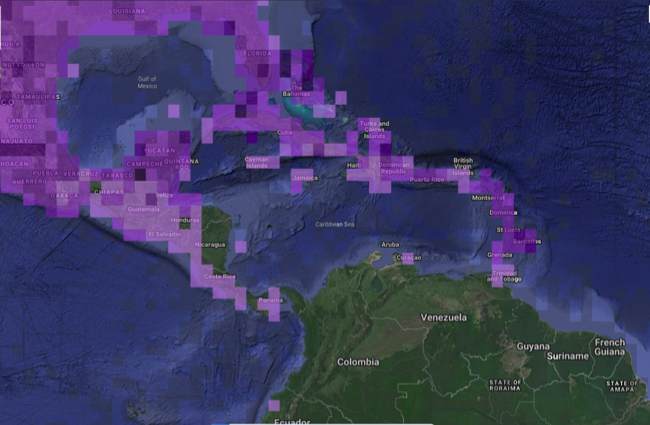

Background: Streptopelia decaocto is known for its strong capacity for

dispersal, e.g. from the Middle East into Europa (Hudson 1965, 1972). In the Western Hemisphere, the species was

introduced initially into the Bahamas and subsequently spread to the

continental North America (Romagosa and Labisky 2000), and is now spreading through Central

American, the Greater Antilles, the Lesser Antilles (Fig. 1). In 2008, Martyn

Kenefick reported the species (without evidence) for the first time to South

America in Trinidad and Tobago; its presence is well known on the nearby

islands (i.e. St. Lucia, Dominica;

less than 200 km distant).

1970

1980

1990

2000

2010

2022

Figure

1. Expansion of Streptopelia decaocto from north to south in America

every 10 years since 1970 (based on ebird data).

Purple squares represent the frequency of records/presence of the species, more

intense purple corresponds to a higher frequency of records.

New

records with evidence: The first insular record in South America with evidence was

made on December 2017 by Michelle da Costa Gomez, who during several days

photographed 1 individual in Curaçao (https://ebird.org/checklist/S41047414, https://ebird.org/checklist/S41046925, https://ebird.org/checklist/S41047372, https://ebird.org/checklist/S41071402). On

February 2020, Luke Dalla Bona photographed one individual in Ecuador (https://ebird.org/checklist/S64789953), but the record being

separated by 800 km from any known established population is suspicious. The Comité Ecuatoriano de Registros Ornitológicos (CERO)

has not formally discussed this record yet, nor one previous photographic

record 270 km to the south (Juan Carlos

Figueroa, February 2020). In Venezuela, the species was photographed in 2018 (https://ebird.org/checklist/S48555365) and 2020 (https://ebird.org/checklist/S83196800); however, the Comité de Registros de las Aves

de Venezuela (CRAV) treated both records as escaped birds because there are

many exotic bird breeders in the area and the first record shows tail damage

caused by captivity.

Finally,

in Trinidad and Tobago a pair was photographed in a residential area of

Chaguanas on 24 May 2020 by Kevin Foster (Fig. 2), and one was seen along Rahamut Trace on 16 August by Faraaz

Abdool; this record was accepted by the Trinidad and

Tobago Birds Status and Distribution Committee (Kenefick 2021). Photos below:

Figure

2. Photographic evidence of Streptopelia

decaocto from Trinidad and Tobago. Photos: Kevin Foster.

Recommendation: We recommend voting yes

for this.

Literature cited

eBird.

2022. eBird: An online database of bird distribution and abundance. eBird,

Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, New York. Available: http://www.ebird.org.

(Accessed: February 1, 2022).

Hudson,

R. (1965). The spread of the Collared Dove in Britain and Ireland. British

Birds 58:105-139.

Hudson,

R. (1972). Collared Doves in Britain and Ireland during 1965-1972. British

Birds 65:139-155.

Kenefick,

M. 2021. Eighteenth Report of the Trinidad and Tobago Birds Status and

Distribution Committee, Records Submitted during 2020. Living World, J.

Trinidad and Tobago Field Naturalists’ Club.

Romagosa, C. M. and R. F. Labisky.

(2000). The establishment and dispersal of the Eurasian Collared-Dove (Streptopelia decaocto) in Florida.

Journal of Field Ornithology 71:159-166.

Jhonathan Miranda and

Juan Freile, February 2022

_______________________________________________________________________________________

Comments

from Lane:

“YES. Another unsurprising expansion in distribution into South American

territory of a species that has exploded across the Caribbean and Middle

America (as shown in those amazing eBird maps included in the proposal!). I

should add that there was a publication (Blancas-Calva

and Blancas-Hernandez 2016) that reported birds from

Lima, Peru, but these reports were rejected by CRAP for lack of convincing

documentation and were likely misidentified Zenaida meloda:

“Literature cited: Blancas-Calva, E.

& J. C. Blancas-Hernández. 2016. Presencia de la

paloma turca (Streptopelia decaocto) en la ciudad de Lima, Perú.

Huitzil, Rev. Mex. Ornitol. 17(1): 111-114.”

Comments

from Areta:

“I vote NO to the inclusion of S.

decaocto in the SACC list. Even when it is likely that the bird in Kenefick

(2021) is S. decaocto, I am not

wholly convinced.

“First

of all, there is no evidence that the species has an established population.

For exotic birds like these, escapees do not constitute enough evidence to be

added to the list. Or is this a recent colonization attempt? Or vagrants? We

don´t know.

“Second,

I am no expert on these doves, but doesn´t the undertail of the T&T bird

look too white for decaocto and more consistent with roseogrisea/risoria?

If you look at the picture published in Kenefick (2021) it does indeed look

quite white and different from several examples of decaocto. Note that

the light in this picture is good to appreciate the color of the undertail

coverts. I would also expect the undertail coverts to be more contrasting in

comparison to the white tail tips in the other photographs that accompany the

proposal (both look rather subdued, perhaps lighting in addition to some dirt?).

Also, the contrast between the primaries and the back does not seem striking

(though the bird is molting, and quite worn). Finally, whether the extension of

black on the outer vane of the outermost tail feathers is useful in separating

these is difficult to assess with these birds in places were

they have been introduced. I looked into the supposed usefulness of the amount

of black on the outermost tail feather when exploring photographs, but my

conclusion was that it was highly variable, at least in relation to the white

undertail coverts (i.e., several birds with white undertail coverts exhibit

black outer vanes as extensive as those shown in the additional photographs

posted in the proposal, while the amount of black/white on the tail is not

visible in the photo published by Kenefick 2021).

“Is

this decaocto or roseogrisea/risora?: https://macaulaylibrary.org/asset/386304911

“Some

decaocto: https://macaulaylibrary.org/asset/414345691 / https://macaulaylibrary.org/asset/414315171

“And

here an example of roseogrisea/risora (or isn´t it?, look at the white undertail and the extensive black

border to the innermost tail feather): https://macaulaylibrary.org/asset/384964051

“The

Curaçao bird also looks pale-primaried (and so warm throughout), never showing

the undertail coverts, but it looks like an escapee of roseogrisea/risoria.

The same applies to the Venezuelan photographs.

“May

decaocto X roseogrisea/risoria

hybrids have been expanding

without much notice across the Caribbean?

“At

present, I am not 100% sure that the birds in the photographs from T&T are decaocto

and we cannot rule out decaocto X

roseogrisea/risoria hybrids

based on current evidence.

“There

are other Streptopelia species that can look deceivingly similar that

need to be discarded if we will be rigorous, and I have seen no attempt to sort

this out here.

“I

would definitely like to hear the vocalizations, which would clinch the ID of

the birds.

“Until

then, I vote NO, in part because the evidence is not good enough to confidently

identify these birds as S. decaocto (based on my current understanding):

some plumage features do not fit convincingly, no comparisons to other Streptopelia

species have been performed, and there are no available sound recordings.”

Comments

from Stiles:

“NO to including S. decaocto in the SA list

until the problems of identification can be resolved. In any case, at the rate

this species seems to be expanding, it may be only a question of a few more

years until definite resolution could be achieved.”

Comments from Hein Van Grouw (solicited by Areta after

publication of Grouw, H. van. 2022. The colourful

journey of the Eurasian Collared Dove Streptopelia decaocto. Bulletin of the British Ornithologists’ Club

142: 164-189):

"The

doves shown in the photos of this proposal have hybrid characteristics. The

head and breast appear to be too pinkish for Eurasian Collared Dove, so that

seems to be a Barbary Dove influence. The undertail coverts of the bird in the

last photo has too much white for an ECD, so also clearly Barbary Dove genes.

As said in my paper (Grouw 2022), I expect the whole population of ECD in North

America to be “impure”. Not all

individuals will show visible evidence of it, but they all carry risoria

genes is my opinion. Whether that would be a reason for not accepting them

is another question I cannot answer.

“These two

birds (see links) below, mentioned in the comments have also very clear hybrid

characters. This one has the white belly and undertail coverts of Barbary dove,

but the coloured outer vanes of the outer tail feathers of Eurasian

Collared Dove:

https://macaulaylibrary.org/asset/384964051

“And this

one is the other way round, grey belly and undertail coverts of ECD, but

lacking the colour in the outer vane of the

outer tail feathers for Barbary dove.

https://macaulaylibrary.org/asset/386304911"

Comments

from Pacheco:

“NO. In light of the comments and information

provided here. As Gary rightly mentioned, it is a matter of a few years that

Eurasian Collared-Dove will be recorded at SA, hopefully, from unequivocal

evidence.”

Comments from Bonaccorso: “NO. Given the extensive

reasoning initially provided by Nacho and the comments provided by Hein Van

Grouw (way to go, Nacho!), I think we are in no position to add Streptopelia

decaocto to the main list.”

Comments from Claramunt: “NO. I agree with Nacho. The

photographic evidence is inconclusive considering that other similar species

may be involved. Interpreting shades of gray or pinkish tints in those photos

is very tricky.”

Comments from Robbins: “NO. Based on the uncertainty on

the identification of these birds, with the possibility that they may even be

hybrids, it would be premature to add the species to the SACC list. So, I vote NO for adding the species at this

point.”

Additional comments from

Lane: If I

understand Grouw’s comments correctly, he is

suggesting that *all* New World “Streptopelia decaocto” are of a hybrid

swarm involving some dilute S. risoria

heritage. This could potentially be a similar idea to all large

white-headed Larus

having some hybrid heritage, or all

Zonotrichia atricapilla

having the mtDNA of Z.

leucophrys gambelii, no? What I mean is: the past history of hybridization doesn’t

invalidate the species status of the population in the latter cases, and given

I don’t see much evidence of hybrid characters within New World

S. decaocto; otherwise,

those are weak reasons at best to consider the source population of the present

records “invalid” as that species. Couldn’t a major genetic bottlenecking event

equally be the cause of the variably paler plumage characters that are seen on

many S. decaocto

throughout its New World distribution? Granted, they have no doubt

encountered and interbred with S. risoria

at a few select places, but it isn’t a snowballing effect, rather

the latter’s genes probably have been greatly diluted by the sheer numbers of

the former as it expands farther. But it seems to me that all this could be

solved pretty easily if recordings of song of these birds could be made

available, as S. decaocto

and S. risoria

sound quite distinct. So, until recordings are provided, I will

switch to NO for now on acceptance of these records.”

Comments from Martyn Kenefick: “I wish to follow up on the debate

concerning these doves. Currently, we currently have a group of up to 35

individuals in a residential/suburban area in central Trinidad, and last week,

two were observed copulating. I attach various new photographs.

We have tried to

get a vocalization recording as per the attached. It is poor, not made any

easier by the high density of traffic in the area. We will continue to try and

get an improved one.

Comments from Remsen: I have given my vote to Marshall

Iliff, who is working on his comments and votes, but I can say that the

attached recording seems indistinguishable from our local Eurasian

Collared-Doves, as do the photos.

Additional comments from Areta: “Thanks Martyn for

providing new evidence, which I find convincing in terms of plumage and song

for S. decaocto. Regarding

the establishment of a small population, 35 birds together regularly seen at

the same place, songs, and a copulation are much better evidence than isolated

sightings. Whether there is hybridization or whether there are some

risoria/roseogrisea genes I

cannot tell, although as Hein Van Grouw wrote, this

is very likely. I also note that there is a sound recording of

risoria/roseogrisea from

Colombia https://xeno-canto.org/455165), but I

don´t know what to make out of it. In sum, given the new evidence, I change my

vote to YES.”

Additional comments from Robbins: “Given the new information, I change my vote to a "YES" for adding the bird to the list.”

Additional

comments from Lane: “Well it appears that my request for a recording has been

answered, and I am satisfied that the voice in that recording is

S. decaocto, so I vote YES (again) to accepting that species

on the South American list.”

Additional comments from Claramunt: “Based on

the new evidence, I change my vote to YES.”

Comments from Jaramillo: “YES -- photos and recordings are clear,

and so is the pattern of expansion.”

Comments from Marshall

Iliff (voting for Remsen): “Van Remsen asked me to vote on this record on his

behalf. In short, I vote YES to accept Eurasian Collared-Dove to the South

American list based on the photos and (especially) the audio recordings from

Trinidad.

“Just for the record

though, this proposal, and early votes from SACC members, were a bit confused

by three separate issues (identification, provenance, and hybridization) which

I think were distracting. I’ll give some additional comments on each of those

issues:

“Species identification

“The initial proposal

included three examples of clear domestic-type African Collared Dove (S.

roseogrisea), also known as Ringed Turtle-Dove or Barbary Dove, and this

clearly made for very confused voting. If only the Trinidad record (the only

one actually pertaining to Eurasian Collared-Dove) had been included then I

think it all would have been clearer.

“Four included records

had been erroneously accepted in eBird as Eurasian Collared-Dove in early 2022

when this proposal was posted, but in fact the photos show domestic-type

African Collared-Dove and should not have been considered as part of this

proposal:

1)

Curaçao

5-13 Dec 2017 (e.g., https://ebird.org/checklist/S41047414, https://ebird.org/checklist/S41047372)

2)

Manabí,

Ecuador, 19 Feb 2020 (https://macaulaylibrary.org/asset/210581941)

3)

Lara,

Venezuela, 15 Sep 2018 (https://ebird.org/checklist/48555365) and 18 Jan 2020 (https://ebird.org/checklist/S83196800)

“EBird reviewers are

humans, and they make mistakes in their reviews sometimes, especially for

really tricky identifications like Streptopelia doves. Mistakes on the

Eurasian Collared-Dove map can get lost in the sea of valid records, and that’s

what happened here and is probably why these were included in the initial

proposal. As soon as the SACC proposal was listed, sharp birders flagged these

for rereview as African Collared-Dove and all were considered “Not Confirmed”

in eBird by March 2022 and some have now been corrected by the observers. This

is the eBird review process working well—any record should be open to later

scrutiny and no review decision is ever final in the face of a reassessment of

the evidence.

“The Trinidad

recordings, and new photos, clear up ambiguity that existing with the initial

set of photos posted. The birds shown sound and look like typical Eurasian

Collared-Doves. These birds were notably hefty, square-headed, big-chested and

also strongly medium gray in the body color without whitish or pale buff in the

upperparts. The primaries contrast strongly with the rest of the body and are

dark gray, almost blackish (vs. medium gray and contrasting moderately on wild

type African Collared). Most importantly, the undertail shows the diagnostic

pattern of Eurasian Collared-Dove, which is that the outermost tail feathers

(which fold below the tail) show a prominent dark subterminal band that then

has a more extensive outer web that extends more than halfway up the outer

rectrix. This gives the impression of two black spikes that stick off the outer

edges of the black subterminal band and is diagnostic (and often critically

important) to eliminate African Collared-Dove (both ‘wild’ type and ‘domestic’

type) since those have pale outer webs for this feather. In combination with

the patterns of distribution in the region (see below) those images alone meant

a strong ‘yes’ vote from me even before the diagnostic audio.

“But with the audio

file now provided the case is even stronger. The recording includes two

diagnostic vocalizations: 1) the hoarse, single note growl “whoooah”

for which is the African Collared analog is a cackling, laughing

“heh-heh-heh-heh-heh-heh” call; 2) the primary song “whoo-WHOO-whoo” for which African Collared has a rolling “oo-rroooo-oooo”. Vocalizations are the very best way to

distinguish these two since the color and structure can be somewhat subjective

to interpret, varies a bit with age and wear, and the undertail pattern can be

hard to see and misleading if e.g., the outer rectrix is missing.

“The recording

is now available here: https://macaulaylibrary.org/asset/529923241

which is part

of this eBird checklist: https://ebird.org/caribbean/checklist/S127224671

“Also, to address Nacho’s comments:

1)

Boulder, Colorado: I’d treat this as a likely

hybrid from an area where African Collared has been audio recorded and Eurasian

Collared is abundant. I asked the observer to update this record and he has

already done so.

2) Photos from Minnesota and Arizona don’t show the undertail pattern well

enough for me to assess, but I don’t see them as problematic for decaocto.

3)

The Puerto Rico bird is from a known hotbed

of hybridization, and I would identify this bird as a clear hybrid for the

reasons Nacho mentioned.

“Provenance

“Although some Eurasian

Collared-Doves are kept in captivity, surely, the more common case is ‘domestic

type’ African Collared-Doves, which are extremely common escapees. These birds

are often exceptionally tame and often occur as just single individuals. This

is easy to explore on eBird now: just zoom in on the orange grid cells on the

African Collared-Dove map (https://ebird.org/map/afcdov1), which blankets much

of the Americas. If you start clicking points you’ll see the pattern: single

birds, very pale, somewhat variable in plumage from more gray to more buff to

more whitish, and often obviously tame (just like the Curaçao, Ecuador, and

Venezuela records above).

“EBird has essentially

zero known instances of escapee Eurasian Collared-Dove in the Americas. The

eBird map has recently been refined to separate Naturalized and Escapee

records, and these data can also be downloaded. Almost all birds on the eBird

map fit a clear pattern of expansion from probably two sources of introduction:

the Bahamas in the early 1980s and central California coast in the mid to

late-1990s, and this can be seen on a time series of eBird maps (as in the

initial proposal). These populations have now joined and have expanded to

almost every part of continental North America, except the Northeast US and far

northern Canada/Alaska. In the Caribbean, the species has island-hopped along

and colonized almost all islands. At the far southern extreme, the species has

colonized Grenada in just the past several years, based on a recent surge of

acceptable eBird records (Jeff Gerbracht, pers. comm.). So their arrival in

Trinidad was a predictable and obvious range extension. Martyn’s updated

comments makes it clear that this colonization has continued, with increasing

numbers and a small breeding population now. We should expect them to arrive in

Colombia, Aruba, Bonaire, Curaçao, and the northern Venezuelan coast as well,

since the habitat is appropriate, and they have consolidated their population

in Panama and the southern Leeward Islands lately as well.

“So there is no reason

to question the provenance of the Trinidad record(s).

“Hybridization

“It is true that

Eurasian Collareds and African Collared-Doves seem to

hybridize regularly on Puerto Rico, especially in the southwest of the island,

and eBird has some good documentation of this (see photo link above). It also

is not uncommon to see a small percentage of paler-than-expected Eurasian

Collared-Doves elsewhere in North America and some or all such birds may

represent hybrids that indicate ongoing gene flow from escapee African

Collared-Doves—or past gene flow from semi-established populations (e.g., in SW

Florida)—that infused African Collared genes in early colonists. This seems to

be van Grout’s point, and while I expect there is plenty of truth in that, it

is not reason to not accept this species as a fully Naturalized part of the

North (and now South) American avifauna.”

Additional comments from Pacheco: “YES. Based on the

unequivocal information from Trinidad presented by Marshall Iliff, I change my

vote to YES.”