Proposal (943) to South

American Classification Committee

Recognize Lepidothrix velutina as a separate species from Lepidothrix

coronata

Background information:

Many authors have suggested that

west-of-Andes populations of Lepidothrix coronata (L. c. velutina

and L. c. minuscula) may deserve species-level recognition apart from

east-of-Andes populations found in Amazonia and the adjacent Andean foothills (L.

c. coronata, L. c. caquetae, L. c. carbonata, L. c.

exquisita, L. c. caelestipileata, and L. c. regalis; Hilty,

2021; Kirwan and Green, 2011; Ridgely and Tudor, 1994; Snow, 2004). However,

factors including the lack of extensive genomic data from across the large

geographic range of L. coronata and the complex plumage variation within

Amazonian populations of L. coronata have posed a challenge to

clarifying the classification of this species group.

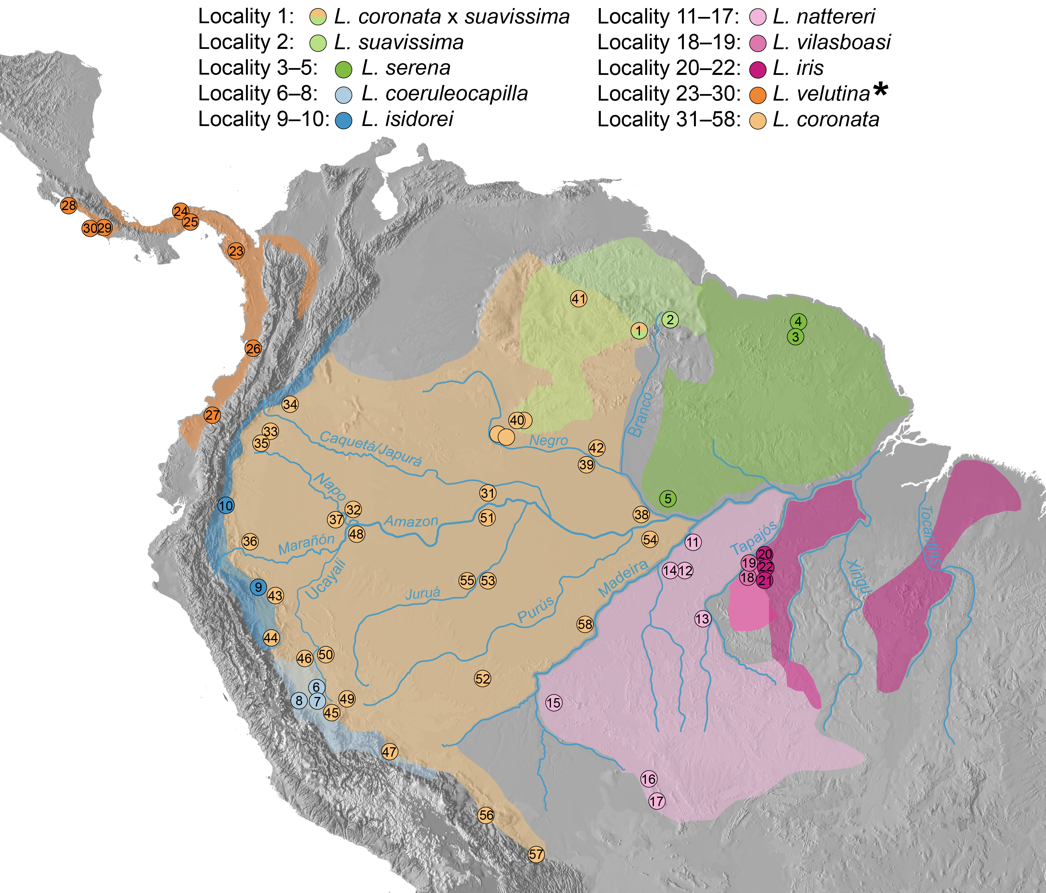

Moncrieff et al.

(2022) published a phylogenetic hypothesis of the genus Lepidothrix with

widespread sampling within the L. coronata species group, including all

currently recognized subspecies (Dickinson and Christidis, 2014). Below is a

sampling map, which includes the proposed L. velutina marked with an

asterisk.

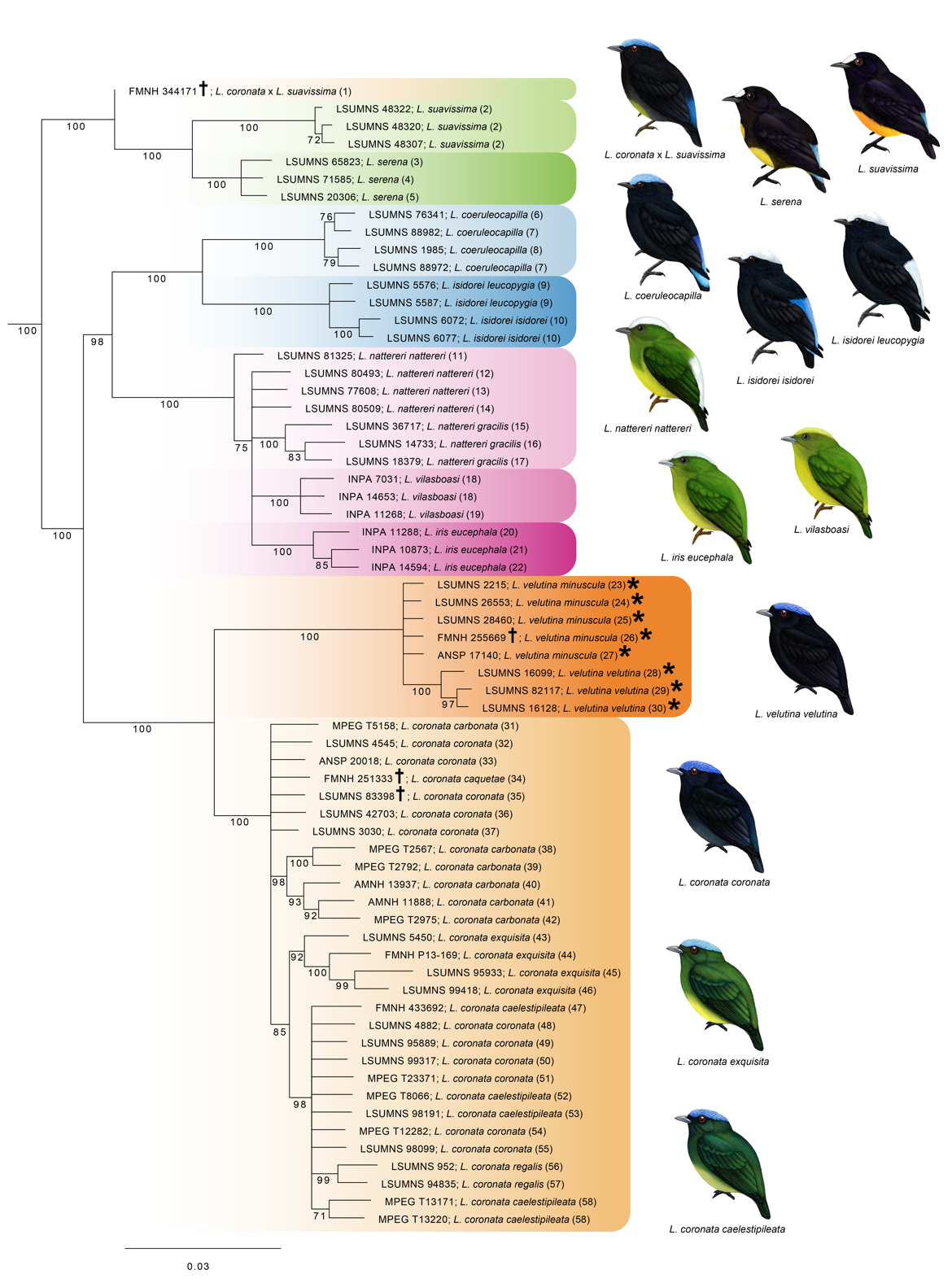

Moncrieff et al. (2022) used both coalescent

and concatenation methods to estimate phylogenies, which consistently

identified a deep divergence within L. coronata corresponding to

west-of-Andes and east-of-Andes clades. Below is a concatenated tree (estimated

with IQ-TREE2 and based on 5,025 SNPs) that is representative of the results

found using other methods and data filtering schemes. Numbers at the end of the

tip labels refer to locality numbers shown on the sampling map above.

Moncrieff et al. (2022) also pointed out that

populations west of the Andes differ markedly in plumage (males have a much

deeper black and more extensive black on forehead) and in voice from

populations east of the Andes. Below we highlight the main vocal differences

with sonograms.

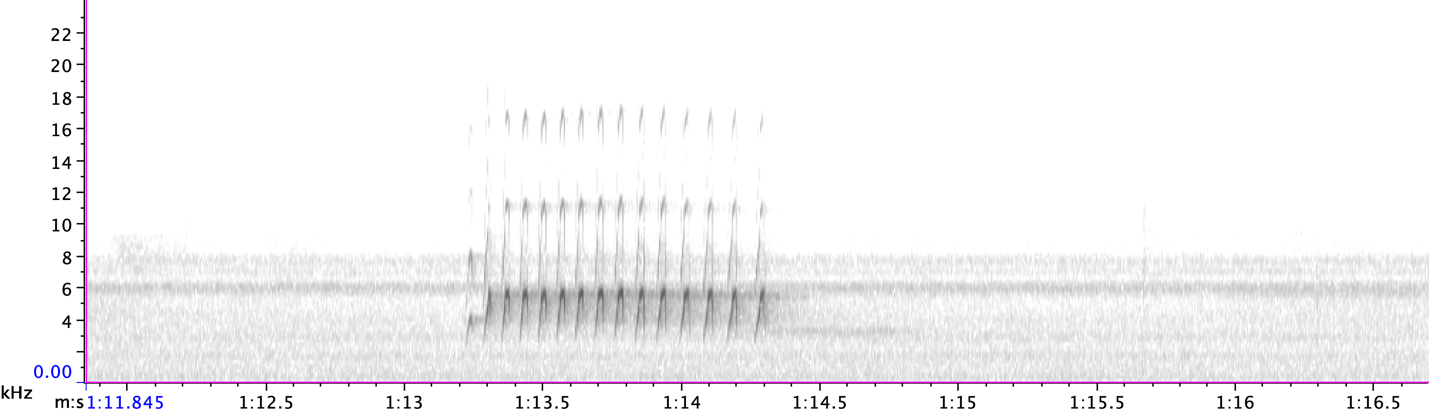

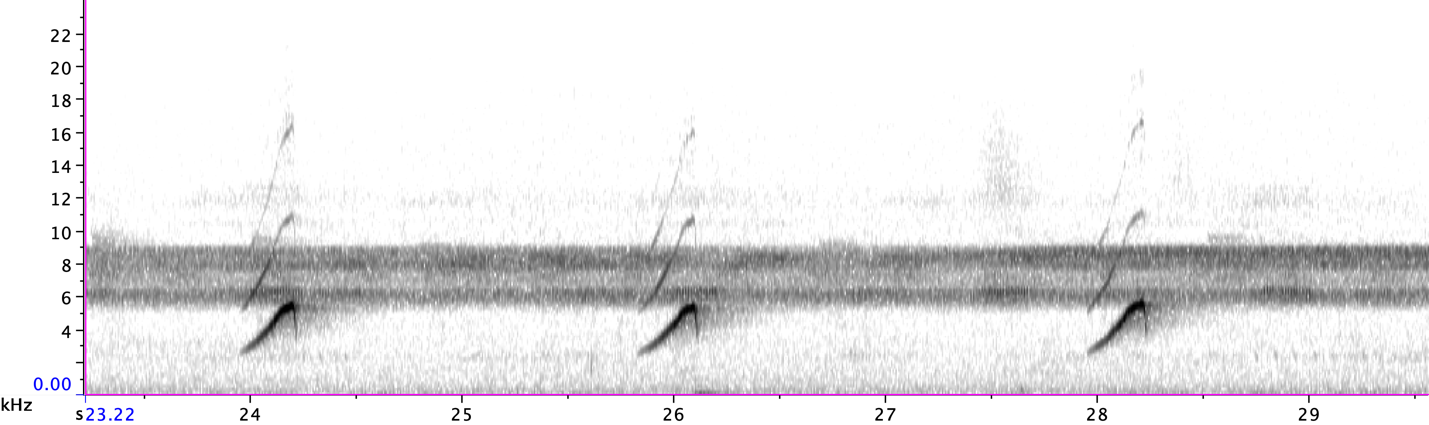

A single trilled primary call from Lepidothrix

coronata velutina. By contrast, east-of-Andes populations of L. coronata

have a sweet, rising whistle as their primary call. Recording by Jay

McGowan from Sendero Ibe Igar, Kuna Yala, Panama (ML202732201).

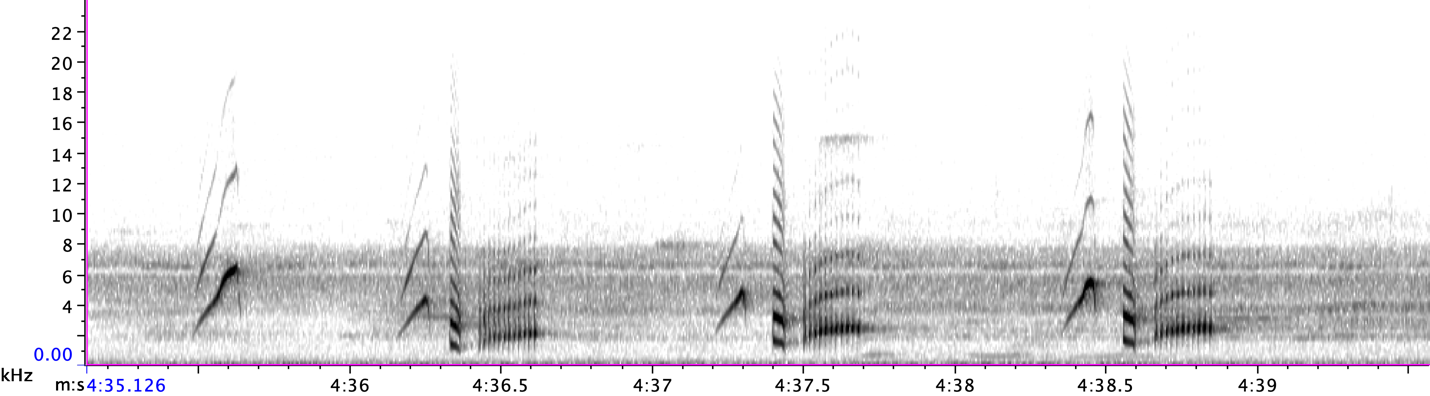

An abbreviated

“ti’ti’t’t’t’t’t’t’t’t” call followed by two “ti’t’t’t’t’t, chu’WAK”

advertisement songs from Lepidothrix coronata velutina. The trilled

calls and trilled introductions to the advertisement song are unique to

west-of-Andes populations of L. coronata. Recording by David L. Ross,

Jr. from Parque Nacional Corcovado, Puntarenas, Costa Rica (ML55245).

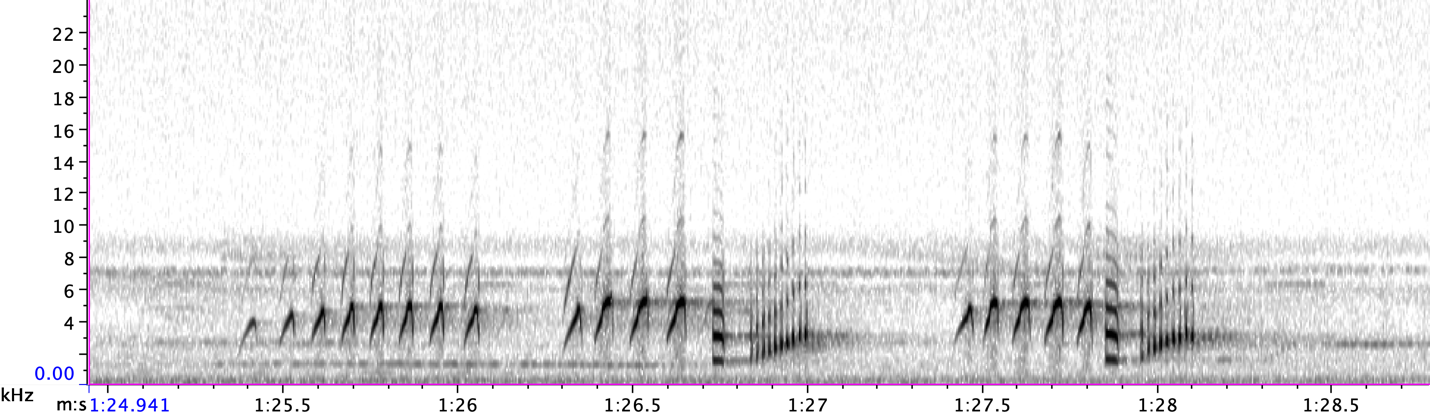

Populations of L. coronata east of the

Andes have males with either a paler black plumage or variations of green with

a yellow belly; they also have a whistled primary call and whistled

introductory note to the advertisement song that is highly distinctive and

consistent.

A series of three

“swee” primary calls from Lepidothrix coronata. This “swee” call given

by east-of-Andes populations contrasts with the trilled call of west-of-Andes

populations. Recording by Curtis Marantz

from Parque Nacional do Jaú, Amazonas, Brazil (ML117006).

A single “swee”

primary call followed by a series of three “swee chí-wrr” advertisement songs

from Lepidothrix coronata. The sweet, whistled calls and whistled

beginning to the advertisement song is unique to east-of-Andes populations of L.

coronata. Recording by Gregory Budney from Bushmaster Trail, Yanamono Camp,

Iquitos, Loreto, Peru (ML34194).

Using locally sympatric species of Lepidothrix

(L. coronata and L. coeruleocapilla) as a benchmark,

Moncrieff et al. (2022) also pointed out that vocalizations of west-of-Andes

and east-of-Andes L. coronata differ more than apparently necessary for

maintenance of reproductive barriers within the genus.

Finally, to provide some more context for the

level of genetic divergences involved, the mean sequence divergence between

west-of-Andes and east-of-Andes L. coronata populations at mitochondrial

gene ND2 is 4.25%, which is greater than that observed between species in the

L. nattereri + L. vilasboasi + L. iris clade (1.4–3.1%) and

between L. suavissima and L. serena (3.7%).

Discussion:

Based on my ongoing genetic work within the

east-of-Andes populations of L. coronata, further splits within the

species group do not seem warranted. Although L. c. exquisita of the

Andean foothills of central Peru is highly distinctive in its plumage around

the type locality, it appears to intergrade with L. c. coronata near the

Marañón River in the San Martín and Amazonas Regions. More sampling in that

area is highly desirable. Also, the voice of Amazonian and east-slope Andean

foothill populations is remarkably consistent. If any further splits are

considered in the future, these would only involve east-of-Andes populations

and should therefore not hold up a split of west- vs. east-of-Andes

populations, which are monophyletic and differ in the various ways pointed out

above.

Recommendation:

This proposal has

three parts:

A. Recognize Lepidothrix velutina (Berlepsch,

1883) as a separate species from Lepidothrix coronata. Lepidothrix velutina would include L.

velutina minuscula (Todd, 1919).

B. Use the

English name Velvety Manakin for west-of-Andes populations, following use by

various authorities (e.g., Hilty, 2021; Snow, 2004).

C. Use the

English name Blue-capped Manakin for east-of-Andes populations, following the

use of this common name by Hellmayr (1929). This would avoid ambiguity in usage

of “Blue-crowned Manakin”.

References:

von Berlepsch, H.,

1883. Descriptions of six new species of birds from Southern and Central

America. Ibis 5, 487–494.

Dickinson, E.C.,

Christidis, L. (Eds.), 2014. The Howard and Moore complete checklist of birds

of the world, fourth. ed. Aves Press, Eastbourne, U.K.

Hellmayr, C.E., 1929.

Catalogue of birds of the Americas. Part 6. Oxyruncidae-Pipridae-

Cotingidae-Rupicolidae-Phytotomidae. Publications of the Field Museum of

Natural History No. 266.

Hilty, S.L., 2021.

Birds of Colombia. Lynx and Birdlife International field guides, Lynx Edicions,

Barcelona.

Kirwan, G.M., Green,

G., 2011. Cotingas and manakins. Princeton University Press, Princeton.

Moncrieff, A.E., B. C. Faircloth, and R.

T. Brumfield. 2022. Systematics of Lepidothrix manakins

(Aves: Passeriformes: Pipridae) using RADcap markers. Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 173. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ympev.2022.107525

Ridgely, R.S., Tudor,

G., 1994. The suboscine passerines. Volume II. The birds of South America.

University of Texas Press, Austin.

Snow, D.W., 2004.

Family Pipridae (Manakins), in: Del Hoyo, J., Elliott, A., Christie, D. (Eds.),

Handbook of the Birds of the World. Vol. 9. Cotingas to Pipits and Wagtails.

Lynx Editions, Barcelona, pp. 110–169.

Todd, W.E.C., 1919.

Descriptions of apparently new Colombian birds. Proc. Biol. Soc. Washington 32,

113–118.

Andre E. Moncrieff, June 2022

_______________________________________________________________________________

Comments

from Remsen:

A.YES. The differences in vocalizations alone are

sufficient evidence for me, regardless of degree of genetic differentiation.

B. YES. Not only does Velvety have a long track

record, but it also is an apt description that is also memorable. The word “velutinus”

means “velvety” in Latin, so that’s nice.

C. YES. Good idea.

This maintains the connection with “Blue-crowned” and has the bonus

advantage of already being used historically.

Retaining Blue-crowned for either daughter species would be contrary to

our guidelines because this is a classic parent-daughter split with both

daughters having large ranges; therefore, retaining “Blue-crowned” for one of

the daughters would lead to perpetual confusion. This is a case in which “stability”

(retaining Blue-crowned) is disadvantageous because the species classification

itself has been destabilized --- time to learn new names to go along with a new

taxonomic concept.

Comments

from Areta:

“A. YES. The deep split, different calls/introduction

to song, and distinct plumages argue in favor of the recognition of L.

velutina. Regarding the common names, I am fine with Velvety. Changing the

name Blue-crowned by Blue-capped seems to create unnecessary instability, for a

bird that encompasses more than 90% of the range and for which no species-level

name change has been made. Whether these are sister or not is immaterial to

me.”

Comments from Lane: “A. YES. Phylogenetic and vocal

datasets warrant this split.

”B and C: YES.”

Comments from Donsker:

“B. YES. Velvety Manakin is an excellent English name for the west-of-Andes

populations with roots extending at least back to Hellmayr.

“C. YES. Use Blue-capped Manakin for the east-of-Andes populations

by restoring a very appropriate Hellmayr name. “Blue-crowned” Manakin would

best be retired, and reserved for the broader species concept, as it was by

Meyer de Schauensee, if the split is accepted.”

Comments from Steve Hilty:

“A. Aside from firm genetic evidence (see Moncrieff

2022, gene tree) the vocal differences between west-of-the Andes, and east of

the Andes populations is striking. Displaying western birds give a soft

rattling trill, this often (but not always) followed by a couple harsh notes.

Displaying eastern birds commonly give a slightly rising two-noted "cha-vick" repeatedly (which I have always assumed to be

advertising, but could be given in other context); and a simple, rather soft

rising "pweeet!" repeated a few times (also

advertising, or given in other context?). In any case, the differences between

the vocalizations of these western and eastern populations are hard to miss. In

fact, to my ears, the two-note call of the eastern birds (carbonata) sounds

most like that of Dwarf Tyrant-Manakin, Tyranneutes stolzmanni, although

the latter's call is harsher, and will always come from mid-levels or higher in

forest (not understory as in case of Blue-crowned (Blue-capped) Manakin.

Moncrieff (2022) also points out plumage differences

between western and eastern birds. Although these differences can be discerned

in the hand in direct comparison, they are (in my opinion) of minimal value at

best for a field observer—especially in the typically low light conditions of

tropical forest understory, where individuals of both populations occur. It is

likely that these relatively subtle plumage differences (if they are important)

are better appreciated in life by the birds themselves, who undoubtedly have

sharper color resolution, than we (humans) do. However, because these two

populations do not overlap, the importance of these differences, in life, may

be minimal.

(voting for Areta)

“B & C: YES”

Comments from Josh Beck (voting for Claramunt):

“B & C: YES. I am in favor of the proposed names (Velvety and

Blue-capped). Velvety has precedence, is unique, is apt, and is memorable. For coronata

(sensu stricto), although the range is, as pointed out, at least an order of

magnitude larger than for velutina, a 10 minute dig into eBird shows

that about 65% of observations are trans-Andean, and about 35% are cis-Andean.

This is obviously tilted by bias in where birders go, where there are greater

numbers of domestic birders, and where eBird is used more, but still clearly

shows that there is observation bias towards velutina, which to

me is a strong argument against retaining Blue-crowned, despite the instability

that will result.”

Comments from Bonaccorso: “YES. The combination of genetic

differentiation, voice differentiation, and very modest plumage differences

(which, I agree with Steve, seem very difficult to discern in the field), make

the case for giving species status to Lepidothrix velutina. Fortunately,

the species do not overlap geographically! Nice proposal, by the way. Proposals

are much easier to evaluate when all the available graphic information (maps,

trees, songs) are included directly in the proposal.”

Comments from Claramunt: “YES. Genetic, plumage, and vocal

evidence point to the species status of velutina. MtDNA shows instead velutina

sister to the N Amazonian forms of coronata (Smith et al., 2014), but maybe

just a case of incomplete lineage sorting.”

Comments from Robbins: “YES for recognizing Lepidothrix

velutina as a species given the dramatic differences in vocalizations and

genetics between it and east of the Andes populations as thoroughly documented

in the Moncrieff et al. (2022) paper.”

Comments from Stiles: “YES on A,B, and C. The genetic

and vocal evidence, as well as geography strongly support splitting velutina

from the cis-Andean coronata group. I find the claim that

retaining Blue-crowned for velutina would go against SACC policy:

the only way this could be possible would be to use Eastern and Western

Blue-crowned for the cis- and trans-Andean species, which would go over like a

lead balloon for SACC, and I very much doubt that the name Blue-capped for coronata

S.S. would cause irremediable confusion for northern birders in Brazil!”

Comments from Schulenberg: YES on B and C. I am totally onboard with Velvety (velutina)

and Blue-capped (coronata) manakins.”

Comments from Pacheco: “YES. Genetic and vocal repertoire data sets provide satisfactory support for this division.”

Comments

from Jaramillo: “A. YES – The vocalization differences are

key in this situation. B. YES – Fits the darker black plumage. Good name. C. YES

– I don’t mind keeping Blue-crowned to tell the truth. If used more commonly,

and affecting a large portion of the range, then keeping Blue-crowned would be

fine. But in this case, as Josh points out the usage is biased to the western

population (vetulina), so that makes it more

complex.”