Proposal (945) to South

American Classification Committee

Split Piranga flava complex into multiple species

Effect on SACC

classification: This would split

our Piranga flava into two or more species.

Background: This is a well-known problem in species limits

that has been dealt with differently by different authors for at least 120

years. Our current note reads as

follows:

Zimmer (1929)

was the first to treat all members of the P. flava group as a single

species, and this has been followed by most subsequent authors, although AOU

(1983, 1998) recognized three subspecies groups, and Isler & Isler (1987)

suggested that each might be better treated as separate species. Meyer de Schauensee (1966) and Ridgely &

Tudor (1989) also proposed that this species probably consists of two or three

separate species. Two of these occur in

South America: nominate flava of southern and eastern South America, and

the lutea group of the Andes region (and also Panama and Costa

Rica). See Zimmer (1929) concerning

earlier claims of sympatry between flava and lutea. Burns (1998) proposed that the three

subspecies groups should be treated as three phylogenetic species, and possibly

biological species, based on comparative genetic distance data within Piranga. Ridgely & Greenfield (2001) and Hilty

(2011) treated the

three groups as separate species. Haverschmidt and Mees (1994) treated the

subspecies haemalea of the Tepuis as a separate species from P. flava

based on habitat differences. Manthey

et al. (2016) found that haemalea was not part of the lutea

group. SACC

proposal needed.

Ridgway (1902) treated

the complex as 2 species, as follows:

1. Piranga

hepatica (Hepatic Tanager): SW USA to Guatemala

2. Piranga

testacea: (Brick-red Tanager: Nicaragua to Bolivia (also with pine-lands

subspecies “Belize Tanager” P. t. figlina from Guatemala to Honduras)

Although many of the

Neotropical subspecies were not yet described, haemalea of the Tepui

region was described in 1883, but was not mentioned by Ridgway, nor was any

member of the even older lowland flava=azarae group of

south-central South America. This might

suggest that Ridgway did not consider them part of this group.

Zimmer’s (1929) 50+ page monograph on the group is the basis of our current

classification. However, this monograph

was written in an era when vocalizations were not taken into account – all

taxonomy was based on external morphology combined with distributional

considerations (e.g., sympatry/parapatry vs. allopatry). Here is Zimmer’s synopsis, and you can see

that similarities between the extreme northern and southern taxa strongly

influenced his reasoning for treating them all as conspecific:

“Examination

of numerous specimens of these forms and certain of their unquestioned allies

has fostered the belief that all are races of a single species whose

distribution extends from eastern Argentina to southwestern United States with

little interruption in continuity, though with lateral extensions into Brazil

and the Guianas and into Venezuela and the Guianas in two lines of development

which meet at their outward extremities. Throughout this extensive group, the

color, general pattern, size, shape of bill, and other major characters are

substantially identical or are subject to variability which largely overcomes

the individual differences. There are certain features of plumage and molt

which seem to be present in all the forms under consideration but which are

different from those of the other congeneric groups. The various forms replace

each other geographically in all parts of the range. Finally, at the northern

and southern extremities forms are produced which are strikingly alike in

racial characters that are not shared by the intervening subspecies.

These considerations together present a

volume of evidence that is more than circumstantial. There is no question that

all the forms under discussion are of common phylogenetic origin. Some of them

are more strongly differentiated than others, some distinctly intergrade with

adjacent forms, while others are separated from their nearest allies by so

slight a gap in proportion to the individual variation in that direction that

the relationship is not seriously impaired. In the following treatment,

therefore, I have considered as races of P. flava all the forms under

discussion”.

Zimmer’s study was perhaps the most thorough

study of a single widespread Neotropical bird of that era. So, this situation is about as different from

an unjustified Peters lump as you can get.

Subsequent classifications all followed Zimmer

on this, including Hellmayr, Storer in Peters, Sibley & Monroe, AOU,

Dickinson & Christidis, etc., except for those mentioned in the SACC note

above and the recent HBW/BLI classification.

Isler & Isler (1987)

summarized the qualitative differences in songs and calls for the three groups,

as well as the rather exceptional range of habitats for a single passerine

species (e.g. from arid pinyon-juniper scrub to edges of cloud-forest). The habitat differences were remarked upon

and noted as exceptional by Zimmer himself. Ridgely & Tudor (1989) proposed

that at least 2 and maybe 3 species were involved.

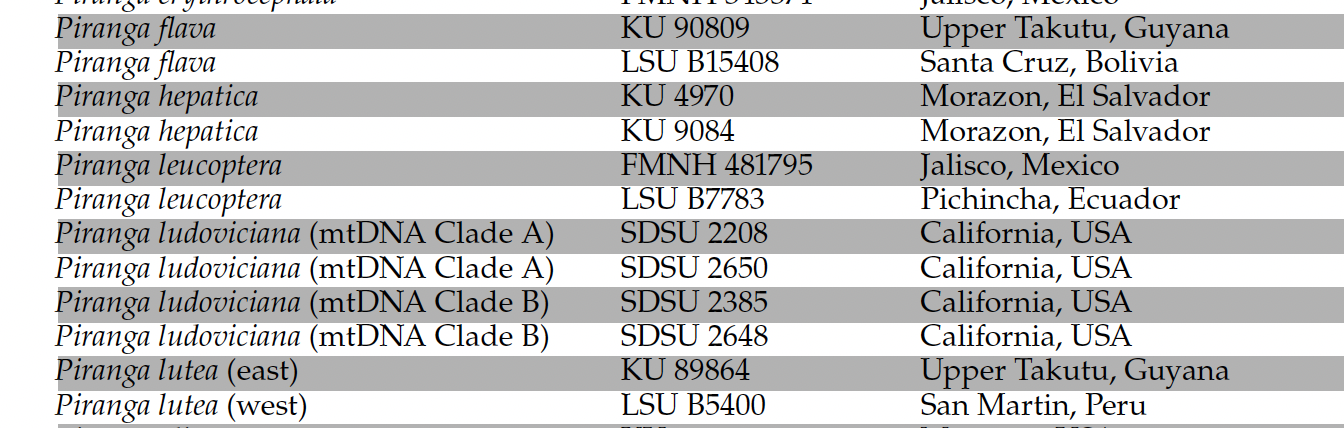

Here is the breakdown

from Isler & Isler (1987), with distribution refinements from Dickinson

& Christidis (2014). Because this is

a complex proposal, I suspect these details might come in handy

(A) hepatica

group (extralimital)

1.nominate hepatica:

highlands of SE California, Arizona, and w. New Mexico S in western Mexico

to Oaxaca

2. dextra:

highlands of e. New Mexico [presumably this species also in Las Animas Co., CO]

and SW Texas south on Caribbean slope to Chiapas

3. albifacies: in highlands of w. Guatemala to n. Nicaragua

4. figlina: lowland pine savannahs of

Belize and e. Guatemala

5. savannarum: lowland pine savannahs of extreme

e. Honduras and NE Nicaragua

(B) lutea

group

6. testacea: highlands of n. Costa

Rica to e. Panama (Darién)

7. faceta: Santa Marta to

highlands of Venezuela; Trinidad

8. haemalea: tepui region from

c. Venezuela, n. Brazil, c. Guyana, c. Suriname

9. toddi: two spots in n. Andes of Colombia

10. desidiosa: W. Andes of Colombia

(Antioquia to Cauca)

11. nominate lutea:

Andes from Nariño S through Ecuador and Peru to c. Bolivia (Cochabamba)

(C) flava

group

12. macconnelli:

lowlands of n. Brazil (Roraima) and the southern Guianas.

13. saira:

lowlands of e. Brazil from Amapá south (patchily) to Mato Grosso and Rio Grande

do Sul

14. rosacea:

lowlands of se. Bolivia e. Santa Cruz)

15. nominate flava:

foothills of E Bolivia from Cochabamba and w. Santa Cruz, S in lowlands to Paraguay, n. Argentina and

Uruguay [note that if the Bolivian records pertain to breeding birds, then this

is not strictly a lowland taxon; however, because this is an austral migrant, I

would not be surprised if these foothill records are wintering birds only –

this needs to be sorted out. ]

Here is the HBW plate

by H. Burn that illustrates 5 of the subspecies:

Burns (1998) proposed that the three subspecies group be treated as

separate phylogenetic and perhaps biological species based on comparative

genetic distance data (cyt-b); however, this was based on just seven specimens,

only one from the lutea group.

Burns concluded: “The DNA data of this study add to

the morphological, distributional, and ecological evidence that suggest that

the three subspecies groups of P. flava represent different

phylogenetic, if not biological species.”

New information

(since the original SACC classification): There really isn’t much in the way of new quantitative data.

Ridgely and

Greenfield (2001; Ecuador book) cited Burns (1998) for their treatment of Andean

lutea group as a separate species (Highland Hepatic-Tanager) from

lowland flava group (Lowland Hepatic-Tanager) as well as the northern hepatica

group (Northern Hepatic-Tanager), as did Hilty (2003; Birds of Venezuela) and

Restall et al. (2006; Birds of Northern South America. Vol. 1); however, note

that Burns was rightfully hesitant in calling them biological species.

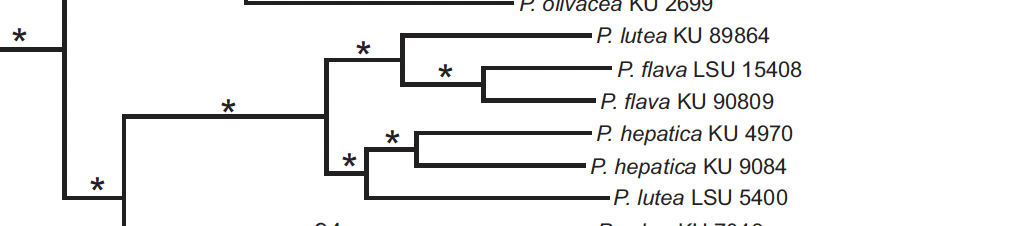

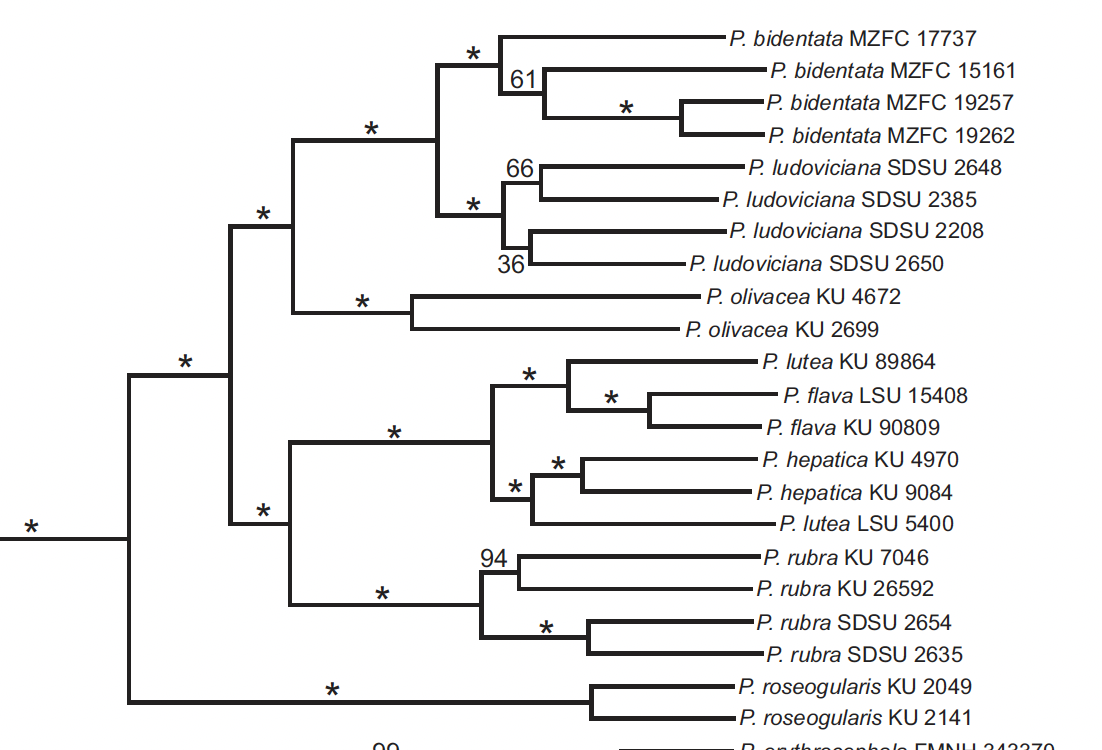

Manthey et al. (2016) used Piranga to compare

different genetic techniques (UCEs vs. RAD-seq). They used only 6 individuals of the flava

complex, two from each subspecies group. Although taxon-sampling was weak, they

corroborated what had been concluded by Zimmer nearly a century earlier, i.e.

that the three groups formed a monophyletic unit. However, they found that lutea, was

paraphyletic: the Andean sample (N. Peru, ergo nominate lutea) was

sister to the two samples of hepatica (from El Salvador, ergo albifacies),

but the sample from Guyana (haemalea) was sister to the two samples of

lowland flava (one from Guyana, ergo presumably macconnelli and

one from e. Bolivia, ergo likely rosacea), both with strong support.

A problem here is that both KU samples from Guyana are

listed as from the same locality (“Upper Takutu”), which is a lowland savanna

locality (fide M. Robbins). For a

second, I thought I’d found evidence of sympatry of lutea and flava

groups, and thus automatic species rank for both.

But

because Manthey et al. didn’t point that out, I suspected an error in their

table. So I checked, and sure enough,

SACC’s Mark Robbins, who collected both specimens (and who obviously was not

asked to go over the paper), told me that this turns out to be an undetected copy-paste

error. From Mark:

“90809: 1.5 km S of Karaudanawa, in the upper Rupununi, i.e.,

lowland site; ID as macconnelli.

“89864: Acai Mts, in the extreme south [of Guyana]! ID as haemalea”

Nonetheless, it still remains that, as Manthey et al.

pointed out, the lutea group as currently constructed is not

monophyletic. The tepui subspecies haemalea

groups with the lowland flava group even though in plumage and

elevation, it fits with the Andean lutea group. Therefore, either the haemalea group

should be transferred to the flava group, which would not make sense

from plumage, or be treated as its own group.

Given that Haverschmidt and Mees (1994) treated haemalea as a

separate species, and that haemalea does not fit with flava in

plumage or elevation, this should be at least treated as a separate, fourth

group in analyses. Finally, that Robbins’

two specimens are only about 150 km from each other, but have such strong

genetic and phenotypic differences, the evidence for treating haemalea

as a separate species from flava, much less lutea, ironically could

be considered stronger than that for any of the other proposed splits even

though it’s never been recognized as a separate group.

Time for a mini-rant.

The above is yet another vivid demonstration of the importance of broad

taxon-sampling. In terms of genetic

sampling, one cannot just assume that a group of subspecies are a monophyletic

group unless all the taxa are sampled.

For all we know, the isolated lutea subspecies in the north group

with haemalea rather than nominate lutea, or form their own group,

or each forms a separate group, or testacea actually groups with

hepatica, or …. .

With respect to Manthey et al., with such limited

taxon-sampling (only 5 of 15 subspecies represented), I find it hard to extract

any firm evidence for species rank either way.

I personally don’t think the use of comparative branch lengths and

genetic distance can be used as a metric for species limits, but even so the

longest branch between the two clusters of Summer Tanager (P. rubra) samples

is longer than any between any of the Hepatic Tanager groups despite the enormously

greater geographic distances among samples of the latter.

By the way, Manthey

et al. is cited as evidence for species rank by HBW/BLI and “IOC”.

As for vocalizations,

Boesman (2016) presented sonograms of songs and calls for each. The N for song sonograms was 3 for flava

group , 3 for lutea group, and 2 for flava group, with location/subspecies

not specified. The N for calls was 4 hepatica,

3 for lutea, and 5 for flava, also with location/subspecies not

specified except for one for testacea in the lutea group, which

appears to be the most different of all.

Here’s what my

impressions are from the sonograms. In

terms of song, I see more differences within the hepatica and lutea

groups as I do between them. As for flava,

the notes themselves do seem on average more complex, as noted by Boesman: “Song of flava group

seems to have the most complex-shaped notes, lacking any simpler-shaped notes.

Many notes are complex underslurred, and apparently there is little variation

in note shape (few different note shapes), unlike other races.” As for call notes,

those of hepatica and flava look very similar to me, but those of

flava look more complex, as noted by Boesman: “Call of flava group is

also clearly different, having an upslurred ending, while both other groups are

about identical, having a very sharp upturned V-shape.“

I suspect Peter Boesman would be the first to tell you

that this sort of sampling and qualitative comparisons has its problems. I will also repeat the same mini-rant that on

taxon-sampling that I did on the genetic data.

Boesman’s studies of this and many other groups are valuable for

pointing out potential issues (note his strange recording of testacea

mentioned above) and can serve as launching pads for more thorough

studies. But until all the taxa are

sampled, with sufficient N and careful attention to homology, their use as

determinants of species limits is perilous.

I think we should be grateful that he has set the table for the more

detailed analyses needed to really sort things out. Lots of potential here, but also lots of

sampling gaps in terms of subspecies and geography. One problem that could be fixed quickly is

that the location and subspecies need to be given for each recording; for

example, three lutea songs are represented, each looking fairly

different. But “which” lutea? They could be from testacea from Costa

Rica, nominate lutea from Bolivia, or any of the other four subspecies

in the group, including even haemalea from the tepui region, which we

now know is not a member of the group.

Or they could all three be from different individuals within any one of

the 6 subspecies.

Just to give you an

idea what the call notes are like, I grabbed a few links:

• A call note from

nominate hepatica from AZ (Richard Webster): https://xeno-canto.org/678668

• A call note from testacea

from Panama (Peter Boesman): https://xeno-canto.org/271527

• a call note from

nominate lutea from Peru (Fabrice Schmitt): https://xeno-canto.org/102734

• A call note from

nominate flava from Paraguay (Fabrice Schmitt): https://xeno-canto.org/616311

• A call note from

haemalea from Guyana (Ted Parker): https://search.macaulaylibrary.org/catalog?taxonCode=heptan&tag=call®ionCode=GY

What stands out to me

from superficial browsing of these and others on xeno-canto is (1) as Boesman

(2016) noted about testacea, that twittered, crossbill-like call seems

to be standard, and if that is the case, then testacea has by far the

most distinctive call; (2) hepatica, lutea, and haemalea

calls sound fairly similar; (3) flava calls are higher-pitched and

slightly inflected, but in the background of the Paraguay recording, I think I

hear another bird giving a lower-pitched call more like northern birds. Obviously, a quantitative analysis of all of

the is needed, with larger N of presumed homologous calls. My gut impression is that when all the data

are analyzed, they will support testacea as a separate species, with the

obvious caveat that this is just from a brief perusal of what is easily

available.

Piranga songs are fairly

complex, and so the final analysis will not be easy. Note that the vocal pattern does not fit the

plumage pattern, e.g. lutea and hepatica are evidently the most

similar vocally, whereas flava and hepatica are most similar

plumage-wise (which is at the core of Zimmer’s rational for conspecificity

Discussion and

Recommendation:

This issue is a real

problem. On the one hand, I share the instinctive

feeling of just about everyone who has commented on the group post-Zimmer that

more than one species is involved, but I would bump it up to at least 5

potential species If this really is to

be treated as one biological species, then the breadth of habitat types covered

would be exceptional, ranging from arid, rocky, pinyon-juniper slopes in the

north to pine savanna to the margins of cloud forest and semi-humid montane

forest to tropical dry forest; the only common denominator might be that the

structure of the habitat is open woodland and edge. (House Wren and Squirrel Cuckoo are the only species

of woodland birds that I can think of offhand that could compete with Hepatic Tanager

for habitat breadth.) But it’s hard to

find conclusive evidence for treating them as separate species. The plumages differ, but not outside the

range of variation for many polytypic species.

The genetic data are too weak to be interpreted either way, especially with

the sampling gaps. The vocal

differences, even qualitatively, between the flava group vs. the other

two suggest multiple separate species, but are the data officially strong

enough for a split?

This complex is

begging for dissertation-level research.

Geographic areas in need of careful sampling are:

(1) the potential

contact areas between haemalea of the tepuis and macconnelli of

the lowlands. They come pretty close in

Guyana and Suriname, but are likely separated by unsuitable habitat: tall tropical

forest. If there is no sign of gene

flow, then that’s all you need to argue for species rank in my opinion, even if

not precisely parapatric.

(2) central Bolivia,

where it is unclear how close lutea and breeding flava come to

each other. The sampling in our Bolivia

book (Herzog et al. 2016) shows a continuous distribution from the Andes of La

Paz and Cochabamba through the foothills of Santa Cruz and Chuquisaca to the

lowlands of Santa Cruz and Tarija. If

these refer to resident populations, then there is a contact zone somewhere in

there, as Hellmayr (1929) noted

Specimens from w. Santa Cruz and Chuquisaca are all assigned to flava

despite their montane distribution. But

we also noted that flava is a partial austral migrant. A first pass through the dates, elevations,

and subspecies identification would likely clear much of this up (but I’m out

of time/energy to do that within a SACC proposal). Hellmayr (1929) did not pick up on the

possibility of austral migrants messing up the distribution. Follow-up

fieldwork in the region might be highly productive. This is the region where lowland subspecies

of Thamnophilus caerulescens meet Andean subspecies, with connecting

populations with intermediate phenotypes and genotypes (Brumfield papers), and

where the same thing appears to be happening in other taxa that have similar

distributions (e.g. Pyriglena leuconota).

The sampling and analysis

of songs and calls needs to be done rigorously, with all taxa sampled. The Piranga I know, including northern

Hepatic, respond vigorously to playback, so careful playback experiments might

be illuminating. Eyal Shy’s dissertation

on North American Piranga songs needs to be read for guidance, as well

as his several subsequently published papers on geographic variation in song within

Summer (P. rubra) and Scarlet (P. olivacea) tanagers. The complexity of the structure of Piranga

songs requires quantitative analyses of their differences with a large sample

size.

I went into this issue

fairly confident that I would find sufficient anecdotal evidence that in

aggregate would make a case for elevating two or three of these subspecies groups

to species rank, but was unable to do so.

The deeper I went, the more complexity was unveiled. Although I am certain that once all the data

are available, we will have evidence for multiple species in the group, I would

be extremely reluctant to change current taxonomy without having a firm

foundation..

Let’s break down the

voting on this proposal as follows:

A YES vote means you

are in favor of splitting up Piranga flava into 2, 3, 4 (or more?)

species, with the precise breakdown to be determined in subsequent voting

round. Note that any vote on

extralimital hepatica would be strictly advisory to NACC.

A NO vote means leave

as is for now.

I recommend a NO

vote. This is a juicy project waiting

for a thorough analysis. I’m not opposed

to piecemeal taxonomy, but I really can’t find any convincing evidence for any

of the splits, as outlined in the details.

I see no immediate rush to resolve this one using fragmentary,

unsatisfactory evidence. Our current

taxonomy certainly masks species-level diversity, but any changes to it could

be considered just as misleading if not fortified by data. Tough decision.

English names: Many classifications that recognize 3 species

use Northern Hepatic-Tanager, Highland Hepatic-Tanager, and Lowland

Hepatic-Tanager for the three groups. They

have had traction in the literature since Isler and Isler (1987). But they strike me as particularly ugly, for

some reason. If this proposal passes,

then I recommend a separate proposal on English names, which would also give us

time for other choices to emerge. For

example, I would consider retaining Hepatic Tanager for the northern group,

contrary to our usual policy for parent-daughter splits, and using Tooth-billed

and Red for the other two groups, just because they have historical precedent,

albeit inconsistent (and not because they are particularly appropriate), and

this is the way IOC/xeno-canto do it.

Literature (partial)

BOESMAN, P. Notes on the

vocalizations of Northern Hepatic-tanager (Piranga hepatica), Highland

Hepatic-tanager (Piranga lutea) and Lowland Hepatic-tanager (Piranga

flava). https://birdsoftheworld.org/bow/ornith-notes/JN100386

BURNS, K. J. 1998.

Molecular phylogenetics of the genus Piranga: implications for

biogeography and the evolution of morphology and behavior. Auk 115: 621–634.

HERZOG, S. K, R. S. TERRILL.

A. E. JAHN, J. V. REMSEN, J V, O. Z. MAILLARD, V. H.GARCÍA-SOLÍZ, R. MACLEOD, A. MACCORMICK,

J. Q. VIDOZ, C. C. TOFTE, H. SLONGO, O. TINTAYA, M., AND J. FJELDSÅ,

J. 2016. Birds of Bolivia : field guide. Asociación Armonía, Santa Cruz de la Sierra,

Bolivia.

ISLER, M., AND P.

ISLER. 1987. The Tanagers, Natural History, Distribution, and Identification.

Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C.

MANTHEY,

J.D., L. C. CAMPILLO, K. J. BURNS, AND R. G. MOYLE. 2016.

Comparison of target-capture and restriction-site associated DNA

sequencing for phylogenomics: a test in cardinalid tanagers (Aves, genus: Piranga). Systematic Biology 65: 640–650,

ZIMMER, J. T. 1929.

A study of the Tooth-billed Red Tanager Piranga flava. Field Museum Natural History, Zoological

Series 17 (5): 169-219.

Van Remsen, June 2022

_______________________________________________________________________________

Comments

from Stiles:

“ Definitely vote NO on this one: this is a

particularly glaring example of the problems arising from insufficient taxon

sampling, with apparently conflicting results from plumage, genetics, and

vocalizations producing an undecipherable conundrum.”

Comments from Robbins: “NO. You have distilled a complex problem down to

where one can at least begin to understand the issues across multiple lines of

data. As you point out, much more data across the entire complex is needed

before we can start elevating taxa to species level. At this point, I concur with your

recommendation of a NO vote.”

Comments from Claramunt: “NO. The new data is just too

sparse to be informative regarding species limits in this widespread and

variable species.”

Comments

from Areta:

“NO. I think that Van´s recommendation is spot on: we

know the currently taxonomy is defective and masking species-level

differentiation within P. flava. But

we lack solid data to make informed decisions as to how the different species

should be circumscribed. The main problems are clear, but the data at hand

falls short to solve them.”

Comments from Pacheco: “NO. I agree with Van's recommendation. The information available for the splits in Piranga – suggested by several sources – is insufficient. Genetic and vocal analyzes have a very low N and unsatisfactory geographic coverage.”

Comments

from Bonaccorso:

“NO. The geographic, taxonomic, and vocal sampling

available is too sparse to make an informed decision.”

Comments from Zimmer: “NO,

somewhat reluctantly, because I think there’s enough smoke swirling around this

complex, that there has to be a fire someplace!

My field experience has told me for decades now that there has to be

more than one species of “Hepatic Tanager”, but, clearly, the evidence is just

too fragmented, and the sampling (be it genetic, vocal or even morphological)

is too weak, with too many gaps, so that basically, we don’t know what we don’t

know. Complex problems usually defy

simple fixes, and I think that’s the case here.

As Van states, this complex is “begging for dissertation level

research.” A couple of observations that

I would just throw out there: 1) To me, testacea is very different vocally,

particularly from nominate hepatica,

both in terms of the unique quality of its common twittering call, and, in the

relative frequency with which it delivers its various vocalizations, as

compared to other taxa in the complex, again, particularly, when compared to

nominate hepatica. I hear that latter taxon singing more than I

hear it delivering its husky, single-noted “CHUCK” calls. With testacea,

the case is a polar opposite, and I hear the unique calls far more frequently

(and when delivered, given more repetitively, in rapid-fire sequence) than I

hear them give the occasional song. To

me, it’s somewhat analogous to situations we’ve commented on before, such as

the Lophotriccus galeatus complex, or

the Zimmerius gracilipes/acer

complex, where populations on the N and S banks of the Amazon may not differ

appreciably in vocalizations, but they do differ in syntax and the relative

frequency with which different vocalizations are given. 2) With respect to the subtle plumage

distinctions between the various subspecies-groups, and Zimmer’s quoted belief

that individual variation swamped any perceived geographic structure to plumage

variation: I don’t have access to the

HBW plate that Van partially reproduced in the proposal, and that partial

reproduction doesn’t include illustrations of extralimital (for SACC) nominate hepatica, but, it has always been my

experience that NONE of the members of either the lutea-group (including haemalea)

or the flava-group with which I am

personally familiar approaches the distinctly dark-cheeked look of male &

female nominate hepatica. That character, by itself, sets hepatica apart, at least

morphologically, from all of the others, in my experience. These types of distinctions in facial

patterns are often obscured by specimen preparation, causing them to be

overlooked or downplayed by someone used to working with skins (as opposed to

seeing the birds in life) and/or by illustrators relying on skins for reference

material.”

Comments

from Jaramillo:

“YES – This proposal has already gone down, but I will go in here with a yes

vote perhaps to encourage someone out there to take this on as a project? I

think we all agree that there is almost certainly more than one species here,

and likely multiple. The uncertainty is how do divide them up because the data are

still lacking. But Yes, I do think there are multiple species, and I would be

willing to chop this up in some way…even if piecemeal and incomplete. I don’t

like to wait for the full story because that story sometimes never comes. But

we do have part of the story.”