Proposal (946) to South

American Classification Committee

Treat Cacicus uropygialis as consisting of three species

Effect on SACC

classification: This would split

our Cacicus uropygialis (Scarlet-rumped Cacique) into two or three species.

Background: The three taxa involved are:

• microrhynchus:

lowlands Honduras to e. Panama (i.e. extralimital to SACC)

• pacificus: lowlands e. Panama south through w. Colombia

to w. Ecuador

• uropygialis: Western Andes and Central Andes of Colombia;

eastern slope of

Andes from NW Venezuela south patchily, it seems, through Colombia and Ecuador

to s. Peru.

The key point to note

immediately is that the first two are lowland taxa, whereas uropygialis

is strictly montane, and more importantly, that pacificus and uropygialis

both occur in w. Colombia; although evidently not precisely parapatric, they

come close, e.g. as per Hilty & Brown (1986), pacificus to 1000 m,

and uropygialis 1500 m and above (but once to 1000 m).

All three are very

similar in plumage, being basically black caciques with red lower backs and

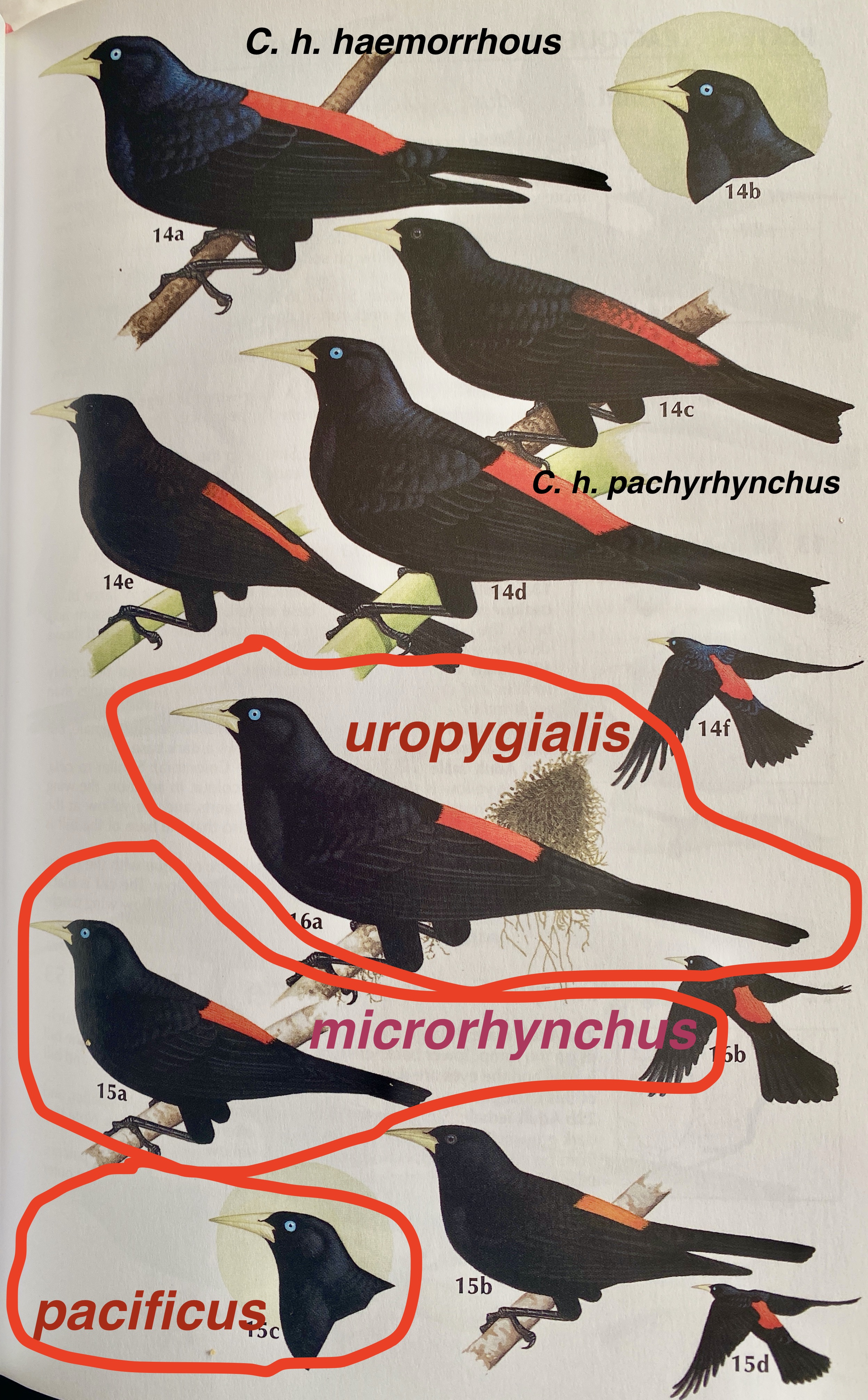

rumps, that differ mainly in slight differences in bill size and shape. Here is Peter Burke’s plate from Jaramillo

& Burke (1999):

Also marked on the

plate are the two subspecies of Cacicus haemorrhous (Red-rumped Cacique),

a lowland species of Amazonia and SE Brazil that is not the sister species to

this group.

This is a well-known

problem in species limits that has been dealt with differently by different

authors for at least 120 years. Our

current note reads as follows:

Cacicus

uropygialis likely includes two, perhaps three, species-level

taxa (Hilty & Brown 1986, Ridgely & Tudor 1989); trans-Andean microrhynchus

was treated as a separate species by Jaramillo & Burke (1999), Ridgely

& Greenfield (2001), and Hilty (2003); Meyer de Schauensee (1966) suspected

that the subspecies pacificus of western Colombia, included by Jaramillo

and Burke (1999) and others as a subspecies of extralimital C. (u.)

microrhynchus, might also deserve species rank. Ridgway (1902) evidently treated microrhynchus

as a separate species from uropygialis by omitting mention of the

latter. Hellmayr (1938), followed by Wetmore

et al. (1984), maintained all as conspecific because of the seemingly

intermediate characters of pacificus.

SACC proposal to

recognize microrhynchus as separate species did not pass because of

absence of formal published analysis.

Powell et al. (2014) found that pacificus was actually sister to uropygialis,

not microrhynchus. SACC proposal needed.

Ridgway (1902) implicitly

treated microrhynchus as a separate species by not mentioning extralimital

uropygialis or of course then-undescribed pacificus.

Hellmayr (1938) treated all three as conspecific with the following

rationale:

“This form [pacificus] combines

the general dimensions of C. u. microrhynchus with the powerful bill of C.

u. uropygialis, thus occupying in its characters an intermediate position

as it does geographically.”

Wetmore (1984) followed Hellmayr and also noted “An

occasional adult male of this race [microrhynchus] shows a faint

swelling on the outer face of the base of the mandibular rami, an indication of

approach to the condition found in C. u. pacificus, but this is not

usual. The 2 races are similar in size.” There is no mention of intergradation. Also: “From the

somewhat scanty data, there may be a gap between the range of this form [pacificus]

and that of C. u. microrhynchus.” And: “The vocalizations of this race include a whistled teeo or keeo,

without the burry quality of the corresponding call of microrhynchus in

the Canal Zone (Eisenmann, in litt.).”

Hilty & Brown

(1986) proposed that pacificus might be a separate species from uropygialis

but noted that strict sympatry was not yet known. Ridgely & Tudor (1989) were sure that the

lowland taxa (pacificus + extralimital microrhynchus) would be

shown to be separate species based on morphological, vocal, and elevational

differences; they suggested Subtropical Cacique for uropygialis and

retaining Scarlet-rumped for the lowland taxa.

Jaramillo & Burke (1999) implemented that split, and their

qualitative descriptions of voices are fairly different. Ridgely & Greenfield (& Robbins and

Coopmans; 2001) also followed the 2-way split.

In 2003, Jaramillo submitted

a SACC proposal to split microrhynchus (including pacificus) from

uropygialis was rejected. To

summarize the outcome of that proposal. most of the committee thought that two

species were involved but did not think the split was adequately supported by

published data. Alvaro summarized in

detail what was known anecdotally in 2003 concerning differences in voices and

jizz – see SACC

73 for all that, which

I strongly recommend reading.

New information

(since a previous SACC proposal

in 2003):

Fraga (HBW 2011)

followed the 2-way split.

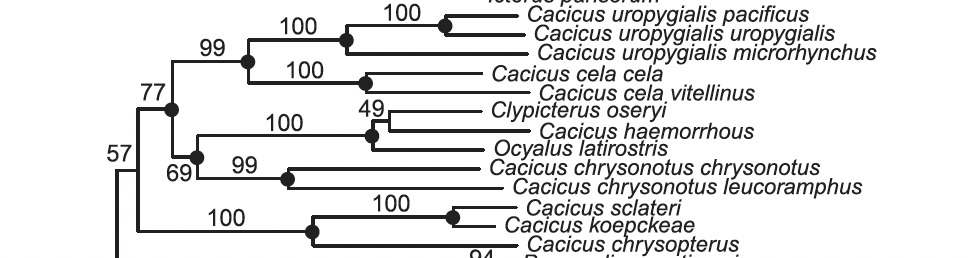

Powell et al. (2014),

using DNA sequence data, produced the following phylogenetic hypothesis for Cacicus:

Note the result that I think would surprise most: pacificus and uropygialis

are actually sisters, not Central American microrhynchus and pacificus. Powell et al. (2014) remarked: “Some authorities (e.g. Jaramillo and Burke, 1999; Fraga,

2011; Gill and Donsker, 2012) recognize Cacicus (uropygialis) microrhynchus

as a species and treat C. u. pacificus as a subspecies of C.

microrhynchus, but mitochondrial DNA indicates

that pacificus is more closely related to C. u. uropygialis.” At face value (as well as eye-balling

comparative branch lengths in the broader phylogeny), this would support

species rank for all three, in my opinion, given the pronounced vocal

differences and near-parapatric distributions of uropygialis and pacificus. The result, however, should be treated with

caution because it might be a case of incomplete lineage-sorting. Also, given the surprise, perhaps the results

should double-checked --- I wonder if there was a mistake in branch labelling

or sample mx-up. On the other hand, the

three taxa are so similar that perhaps we should not be surprised that the

genetic relationships don’t match our non-genetic assessment. Up until Powell et al. (2014), no one had

considered the possibility that the two lowland, parapatric taxa were not

sisters.

Boesman (2016) presented sonograms

of microrhynchus and pacificus (uropygialis not

considered) and stated:

Vocal difference between the

two races is quite obvious in all homologous vocalizations:

* single notes: nominate

utters irregularly overslurred notes reaching max. frequency of 3.2 - 4kHz, pacificus

principally downslurred notes reaching max. frequency of 2.2 - 2.6kHz.

* fast rattling series: A

similar difference in max. frequency and nominate often combines two series of different

repeated notes.

He presented

sonograms of 7 pacificus and 11 microrhynchus (1 Honduras, 5

Costa Rica, 5 Panama). The sonograms

look different, but there is a lot of variation within each, as might be

expected from the considerable repertoire of most Cacicus. Boesman noted the absence of recordings from

eastern Panama and Colombia from near the putative area of contact, but clearly

considered the evidence presented as worthy of species rank.

I played around with

sample recordings of all three on xeno-canto.

With the remarkable variability in vocalizations, it was quickly obvious

that casual browsing wouldn’t produce anything but trouble. Those with more patience of course may pull

some signal out of all those noises. I

will say that uropygialis “sounds different” from the other two, with

the notes having a different, querulous quality that somehow reminds me of

(don’t laugh) Crotophaga ani. I

can certainly see why the genetic results of Powell et al. (2014) should

surprise people.

Discussion and

Recommendation: I hesitate to make taxonomic changes without

solid, published data, but in this case I lean towards a 3-way split for the

following reasons. First, in contrast to

the previous proposal on Piranga rubra, the original lump of the three

was based on a 1938-genre qualitative assessment of size and bill characters

that suggested that pacificus was intermediate, and thus is a “bridge”

between microrhynchus and uropygialis. This would be insufficient evidence by recent

standards. Second, the plumage

differences among taxa that are for-sure species in Cacicus are not very

large; for example, see the illustration above, in which it is difficult to

ascertain differences between C. haemorrhous and the group covered in

this proposal, despite them not being at all closely related within the genus. Third, with all appropriate caveats, the

voices of the three are evidently different, especially uropygialis vs.

the other two, yet genetic data suggest that uropygialis and pacificus

are sisters

Fourth, and most

important to me, is biogeography. Although

perhaps so similar that intergrades would not be detected, microrhynchus

and pacificus are nearly parapatric without any signs of gene flow. Although there is no physical barrier between

the two, range boundaries that end or begin in Darién, Panama, are numerous ---

perhaps one of the most prevalent distribution patterns in Central

America. Going way out on a limb …. This

implies to me that ecological conditions change fairly abruptly in that region,

perhaps caused by differences in rainfall.

If that’s the case, then perhaps the microrhynchus and pacificus

genomes are incompatible to the extent that interbreeding is prevented or

limited. More impressive to me is the

near-parapatry of pacificus and uropygialis in western

Colombia. Again, there is no physical

barrier between the two – the two populations are likely within sight of each

other. Yet there is no sign of gene

flow. What that tells me is that these

two populations have diverged to the point that they have adapted to different

ecological conditions, and neither has conquered the conditions in the minor

elevational gap (if there really is one).

In contrast, if they were the same species, then I would expect free

gene flow and a continuous distribution of the two taxa if they were two

species, with a zone of intergradation at intermediate elevations. Parapatry without gene flow is prima facie

evidence for species rank.

I need to invent a

term for the distribution pattern in which two taxa may not be in direct

physical contact but rather are separated only by habitat that is evidently

unsuitable to either population. For

reasons outlined above, I consider this as evidence for species rank. If the two populations were separated by a

physical barrier, then I would label them as allopatric, regardless of the

width of the barrier, because it appears to be physical limits to dispersal

ability, i.e. extrinsic factors, that are keeping two populations from contact,

in contrast to the intrinsic factors that keep these two pairs of taxa

apart. (By the way, I am working on a

short paper on this as an operational criterion for species rank, so feedback

welcomed. I’m also groping for a term to

describe this near-parapatry situation that doesn’t imply a distance criterion,

so if anyone has suggestions, fire away.

The best I can come up with are unsatisfying: “quasi-parapatry” and

“effective parapatry.”

There are actually 4

possible taxonomic treatments of the complex:

A. No change, i.e.

one polytypic species.

B. Two species: (1) uropygialis

and (2) microrhynchus + pacificus (as in many recent

classifications)

C. Two species: (1) uropygialis

+ pacificus based on the relationships in Powell et al., and (2) microrhynchus

D. Three species: (1)

uropygialis, (2) microrhynchus, (3) pacificus

So, for voting

purposes, a YES means 3 species, i.e. option D, and a NO means one of the other

options, which will then be voted on in a subsequent proposal if D (three

species, the title of the proposal) is rejected.

English names: I favor a separate proposal on English names

if this one passes. The simplest

solution would be to go with the flow as in recent literature and use Pacific

Cacique for pacificus, Subtropical Cacique for uropygialis, and

retain Scarlet-rumped Cacique for microrhynchus s.s. Those names don’t have too much traction,

however, so reasons for a second look are as follows. Many, including me, don’t like using

“Pacific” for non-marine or non-insular species. There is precedent for it, yes, but that

doesn’t mean it’s good. Second,

retaining Scarlet-rumped for microrhynchus bumps up against our guidelines

for English names in parent-daughter splits, and all three have identical

scarlet rumps, so the name is not useful and causes perpetual confusion because

it has been applied to THREE separate taxonomic concepts: broadly defined uropygialis,

microrhynchus + pacificus, and just microrhynchus. On the other hand, Scarlet-rumped works well

within the context of Central America, and although its range is small,

certainly it is the most frequently seen and studied scarlet-rumped cacique

because of its presence in heavily visited Costa Rica and Panama. Ridgway (1902), by the way, used Small-billed

Cacique for microrhynchus, and that indeed is one of the only

differences between it and pacificus.

This one is really a NACC issue, so they should have say over that,

however. Also, some might favor a

hyphenated group-name approach, e.g. Subtropical Scarlet-rumped, etc.

Van Remsen, June 2022

_______________________________________________________________________________

Comments from Areta:

“I vote NO to options A and B, as both seem untenable on

morphological and (to some degree) phylogenetic grounds. Now, deciding whether

one goes for C or D is more difficult. In principle, I am happy to adopt option

C, and may extend onto D if enough convincing data is provided.

“YES to the split of microrhynchus as a separate species. The deep

split from uropygialis and pacificus coupled to their geographic

distributions satisfies me to grant species status to microrhynchus. I

examined a few hundred of eBird photographs. As the name implies, the bill of microrhynchus

does look more slender (i.e., relatively shallow and long bill, note also the

possibly straighter culmen) in comparison to the thicker, relatively broad and

proportionally shorter bills with presumably more curved culmens of uropygialis

and pacificus. Very importantly yet possibly omitted from all

descriptions, the bill of microrhynchus is also noticeably paler than

the bills of both uropygialis and pacificus (i.e., the bill of microrhynchus

is of an ill-defined greenish-yellowish tone, with a somewhat brighter base, whereas

the bills of uropygialis and pacificus have a striking yellow

base; possibly more extensive in uropygialis?).

“Maybe yes to the split of pacificus from uropygialis. The

overall bill proportions, shape and color (assessed through eBird photographs)

are similar, in nice agreement with phylogenetic data in Powell et al. (2011).

The differences in size reported in Jaramillo & Burke (1999) are striking

and, if constant throughout their ranges, are possibly the best additional bit

of information in favor of species status for pacificus, which is the

"lowland" form though possibly reaching altitudes equivalent to those

of the montane uropygialis. May these sizes be adaptive? I have not

studied the vocalizations in detail and although my cursory examination

suggests that the calls are different (simpler and bolder in pacificus,

more complex and softer in uropygialis; some birds do not fit the bill,

perhaps misidentified to ssp.?) I would like to see more rigorous bioacoustic

comparisons (these are caciques!), and I have not assessed whether the

proportionally longer tail of uropygialis reported in the literature

passes a photographic test (though looking at the measurements it should be

obvious). I would also like to see a stringent morphological study across

space, in order to test whether the size differences hold or there is clinal

variation and an assessment on whether the populations to the east and west of

the Andes spill to one or the other side, meet somewhere, etc. In sum, although

a split seems likely, I would like to see a more detailed case.

“I also note that the reduced number of samples in Powell et al.

(2011) will be unable to uncover more complex gene flow or contact areas

scenarios, and is largely driven by mitochondrial DNA. The two microrhynchus

samples are from Panama, the single sample of pacificus is from Ecuador

(Esmeraldas) and the single sample of uropygialis is from Ecuador

(Morona-Santiago).”

Comments

from Stiles:

[YES]

“Gathering

what data I can from my field notes and collections, I can make some

contributions regarding proposals 946 through 948. In this, I have put together

data on weights with those for wing

lengths and tail lengths. Taking the cube roots of the weights of each taxon

and dividing the linear values for wings and tails, I obtain values of these

adjusted to their absolute lengths: relative values independent of absolute

size. I have found such values very useful for hummingbirds, and they here

provide useful insights for the Cacicus as well. I haven’t gone into

this for bills because I suspect that the most useful measurement would be the

height of the bill at the nostril, for which I have no data for microrhynchus.

I didn’t take these in Costa Rica (except for hummingbirds, and then only

in visits following most of my work there). Because these caciques are

typically canopy birds, they don’t often get caught in mist nets, so sample

sizes are small, and there are holes in the data (I lack data for females of uropygialis,

tails for microrhynchus, and weights of females for pacificus,

so here I give only data for males.

C. microrhynchus: mean weight: 68.7g;

mean wing length: 136.5mm; relative wing length: 33.32.

C. pacificus: mean weight 80.1g;

mean wing length 136.25mm; mean tail length 90.15mm; relative wing length

31.60; relative tail length 20.11.

C. uropygialis: mean weight 87.6g;

,mean wing length 143mm; mean tail length 103.7mm; relative wing length 32.24;

relative tail length 23.35.

“These

data tend to confirm the suggestions that microrhynchus does have

considerably relatively long wings, and that the tail of uropygialis is

indeed relatively longer than that of pacificus. The latter, appreciably

heavier than microrhynchus but with wings very similar in length, would

seem to be a more robust bird, probably with higher wing loading and differing

flight characteristics (but wing areas would be needed to confirm this). All this would add evidence favoring

recognition of pacificus as a separate species. Hence, I will vote YES

to adopting the three-species option D in proposal 946.”

Comments

from Fernando Machado-Stredel: “I think it is important to note that the plumage similarity

between haemorrhous and the other caciques with red rumps may not be

rare, with some recurrent plumage patterns being common between non-sister taxa

within Cacicinae. For instance, one could think on the pairs Cacicus

koepckeae - Cacicus chrysonotus chrysonotus (both with yellow rumps), Cacicus

sclateri - Cacicus solitarius (all black), or Cacicus cela - Cacicus

chrysonotus leucoramphus (both with yellow rumps and a yellow wing patch,

although in cela the yellow extends to the vent). In these cases, one

taxon is larger than the other.

“The

measurement data from Jaramillo & Burke (1999) shows that in the

"red" caciques, haemorrhous is the largest, also differing in

the size of the rump patch (as Jaramillo mentioned in proposal 73), followed by

nominate uropygialis, which has longer mean wing and tail, as well as no

overlapping ranges with the other two smaller taxa in these measurements. Cacicus

u. microrhynchus and C. u. pacificus do overlap in these traits.

Here are the data for males:

C. h. haemorrhous (n=28): wing 175.8 (168-187.5); tail 105.9 (100-115)

C. uropygialis:

wing (n=8) 156.5 (145-165); tail (n=9) 129.6 (107-142)

C. m. pacificus (n=10): wing 132.2 (122.2-137.2); tail 91.1 (87.8-94.9)

C. m. microrhynchus

(n=10): wing 129.0 (122.0-136.5); tail 89.7 (83.3-96.5)

“Lastly, I wonder

if the pacificus sample (ANSP 182884) from Ecuador used in Powell et al.

(2014) could be compromised, in which case, contamination may play a role in

the observed phylogenetic relationships.”

Comments

from Claramunt:

“NO. The situation is far from clear. Previous evidence was

interpreted as suggesting that pacificus should be separated but the new

genetic evidence contradicts that. We clearly don’t have much evidence for

splitting (and how) this species. I always like to see measurements, but just

looking at taxon averages, without an assessment of variation or potential

clines, does not inform much regarding potential species limits.”

Comments

from Robbins:

“YES. Taking

the Powell et al. (2014) genetic data as a correct representation of

relationships, this is still a difficult proposal to evaluate. I would prefer, like the recent Trogon rufus

proposal, to have data from that key area of potential contact in northwestern

Colombia. If uropygialis (sensu stricto) and microrhynchus do not

hybridize or is limited then clearly at least two species should be recognized.

That coupled with pacificus being

more distantly related (a surprise, because of the biogeography) to the other

two, would argue for it also being recognized as a species. Finally, if Boseman (2016) is correct in

stating that microrhynchus and pacificus are so different in

vocalizations, then that supports species recognition for those. Although I’m still on the fence on this, the

preponderance of information at this point makes me think we should go ahead

and recognize three species until there are data to indicate otherwise.”

Comments

from Pacheco:

“YES to D. Considering the distinctions available for

morphology, genetics and vocal repertoire. Added to this is the suggestive

information gathered by Gary and, finally, to realize that the historical

lumping of the three taxa was merely arbitrary.”

Additional comments from Stiles: “Upon consulting

Ridgway, vol. 4 (19xx), I found that he also presented data on length of culmen

from base (CfB) and Bill height at base (BHb) for both sexes of C. microrhynchus

(as well as wing and tail lengths) for both sexes. To compare these with

our specimens of pacificus, I measured the same bill dimensions of

these: The results-Valle del Cauca

“For

bills: the ratio of CfB/BHb) for males: microrhynchus

= 2.702; ; for pacificus = 2.221; therefore, the bills at base are

taller relative to their lengths in pacificus, thus supporting the

statement that their bills are “more powerful” than those of microrhynchus.

“Considering

distributions, Hilty (1986, 2021) showed that the ranges of pacificus and

uropygialis in Colombia are mostly separated by the dry valley of the

río Cauca, and only intersect in two areas: the upper río San Juan region in

Valle del Cauca (the only extension of uropygialis onto the Pacific slope – and also the same area as

the W part of the hybrid zone in Ramphocelus studied by Sibley and

Morales, but Hilty explicitly noted that here the two Cacicus separate

by elevation), and at the extreme northern end of the Central Andes, where uropygialis

is mapped in the mountains and pacificus in the adjacent Sinú

lowlands (but I know of no observations or specimens that explicitly document

such a separation here).

Comments

from Bonaccorso:

“NO (no change for now). Plumage differences are weak

at best. The DNA data is for one sample of each subspecies (yes, the branch

lengths are long, but the sampling is too small!) and only mitochondrial genes.

Even if the tree showed the actual relationships among these taxa, there is no

way of detecting admixture between C.

u. pacificus and C. u. uropygialis with such a sparse sampling. Also, if they intergraded, it

would be almost impossible to notice it by plumage. It seems that the vocal

information from Boesman and other sources would be a good start but need to be

analyzed in a quantitative way.”

Additional comments from Stiles: “A minor disagreement with

Elisa, that the plumages of pacificus and uropygialis are

indistinguishable. Strictly on plumage, yes, but given the great difference in

measurements between these two, any intermediate specimen would be easy to

detect by measurements (and so far, none has been detected though, admittedly,

no one so far has specifically tried to collect at intermediate elevations).

Regarding the possible contact zone in N Antioquia, Andrés Cuervo has

definitely recorded uropygialis at > 1500m, but the rest of the transect

remains unstudied (probably unsafe to try at present).

Comments from Lane:

NO. Whereas I suspect that this complex will require splitting at some

point (much as C. cela, and probably C. chrysonotus will as

well), I don’t feel that Powell’s phylogeny is sufficient for us to assess the

true phylogenetic relationships among these taxa. A far better-sampled study

would go a long way to illuminate these relationships satisfactorily.

Furthermore, I don’t hear super-distinctive vocalizations from the three taxa

for me to say that they can’t be simply subspecific variation. Therefore, NO on

splitting this complex based on the present information.”

Comments from Jaramillo: “YES – Treat the three as different

species. Icterids are troublesome is what I have to say! The issue is that you

would expect that birds which are colorful, or have a single distinct color

region on a largely black body, would sort out easily based on plumage. That is

to say, they are not tyrants or furnariids in which species can look exactly

the same, or we discount plumage as a feature to look at, because we have

little to look at. Icterids are often boldly colored, so our expectation is

that different taxa should differ significantly in plumage, but ironically,

they do not do this. Look at Tricolored and Red-winged blackbirds; Western,

Eastern and Chihuahuan meadowlarks, or recurring patterns that are extremely

similar from birds in separate genera, or subgenera (Yellow-winged vs

Yellow-shouldered blackbirds; various orioles…. Etc.). Then we have the big

mess of yellow rumped, black rumped, and red-rumped caciques. In short, I think

that we are expecting that good species in this group should show a distinct

feature, differences in the rump color perhaps? But they do not. The

differences tend to be in their ecology, voice (although difficult to sort out

given how complex the voices are), or size and structure. This is the problem

here.

“Basically, we almost don’t believe the

molecular data because our expectation is that they should look more different

than they do. Yet if we had the same phylogeny and they were Zimmerius

tyrannulets, that would not concern us. It is not a fair comparison, as the

tyrannulets would likely have quite obvious simple differences in voice. Although

icterids are complicated in voice, so much so that even when there are clear

differences as in eastern vs western Great-tailed Grackles, the multiple voices

given in different contexts confuses the listener so much that most experienced

birders have not noticed the differences when they visit the range of the

western vs eastern clade. I think something similar is going on here. The

voices are different, but it takes some analysis to get at that. Fortunately, a

bit of that has been completed, as noted in the proposal.

“There are other differences, as Gary notes the

measurements, the bill structure and relative tail lengths etc. Notably if you

riffle through photos of microrhynchus and pacificus and just

concentrate on the bills, they are quite different. The larger billed pacificus

has a similar length bill to microrhynchus, but the base is thicker,

specifically it looks thicker on the maxilla. This creates almost a casqued

look on some individuals. The form microrhynchus has a thinner bill, but

also a more noticeable downward curve nearer the tip. One would surmise the

different bill sizes on a similar size bird is telling us something about their

differing ecology? As well, there are subtle coloration differences. Bill

colors differ quite a bit in the cacique – oropendola group; it is unclear if

these have any role in mate selection. If you look carefully at a series of microrhynchus

bills, they are yellow but show a dull greenish wash to the bills. Overall,

they are duller; whereas on pacificus, they are yellowish but have a

distinctly brighter base, some nearly orange at the base, and becoming more

greenish yellow towards the tip. Adding in the much larger uropygialis,

it is more extreme in the bill thickness, and has a much more noticeable bright

colored base to the bill.

“It would be great to have more

information on coloniality in these birds. It seems that some populations are

colonial, and others are solitary. Yet these details are not well known, and

unclear how they map on to the three taxa. The three are divided geographically,

but as you would expect also ecologically. This has been one of the key issues

that had led many to separate “Subtropical Cacique” uropygialis from the

others given its different elevational range. The idea Van focused on,

regarding the break in the Darien is important. The two smaller subspecies were

formerly lumped due to similarity in size, and plumage. But the fact that they

are nearly touching, no evidence of intermediates, and differences in bill

shape suggesting differences in what they feed on are important. Voice is

different as well for those two.

“I think these are three different species and

feel comfortable making the change. The molecular phylogeny is vital here, but

take the similarities in plumage with a grain of salt. This is not unusual in

icterids, and surely, we will have more splits in the future in this family

where plumage is not as informative as we would think it should be in brightly

colored species.”

Comments

from Zimmer:

“YES to D, for reasons stated by Mark, Gary, and Alvaro. As Alvaro says, “Icterids are

troublesome”. Plumage patterns are

clearly highly conserved in this group, and vocalizations are complex (including

advanced mimicry abilities among some species), making traditional vocal

analyses difficult. In this case, the

morphometric and genetic differences, combined with lack of evidence of

intermediacy from potential contact zones, and apparent qualitative differences

in at least some vocalizations, are enough to sway me.”

Comments

from Areta:

“NO. "After

waiting for input on the key issues on whether the vocalizations do indeed

differ as I think they do between pacificus an uropygialis, and whether the size differences are constant

throughout their ranges (in opposition to the existence of a cline in

measurements and proportions), I vote NO to the split of these two: they are

sister, and a full-fledged study will be very enlightening."