Proposal (948) to South

American Classification Committee

Treat Flame-rumped Tanager (Ramphocelus

flammigerus) as two species

Background:

The Flame-rumped Tanager (Ramphocelus flammigerus) occurs

from Panama south through Colombia to southwestern Ecuador and adjacent

northwestern Peru. It consists of two subspecies: R. f. flammigerus in

the northern part of the range and R. f. icteronotus in the southern

part of the range. They meet and hybridize above 800 meters in the western

Andes of Colombia. Both males and females of each subspecies have very

different plumage. Males of both subspecies are mostly black, but R. f.

flammigerus has a bright red back and rump, whereas R. f. icteronotus

has a yellow back and rump. Females of R. f. flammigerus also have a

reddish orange band across their chest and reddish-orange rump, undertail

coverts, and uppertail coverts, whereas females of R. f. icteronotus are

solid yellow below and on their rumps

Taxonomic

lists and regional field guides differ in how they treat these two taxa:

The

two forms are treated as subspecies of the same species by Storer (1970),

Ridgley and Tudor (1989), Sibley and Monroe (1990), Dickinson (2003), Hilty

(2021), and Clements et al. (2021). They are treated as separate species by

Meyer de Schauensee (1970), Hilty and Brown (1986), Ridgely & Greenfield

(2001), Restall et al. (2007), del Hoyo and Collar

(2016), and Gill et al. (2022).

The HBW-Birdlife list (del Hoyo and Collar 2016) provides the

following rationale for treating them separate: Usually treated as conspecific

with R. flammigerus, and genetic differences apparently minimal;

moreover, owing to recent deforestation the two taxa now reportedly meet and

interbreed in W Andes of Colombia (along a narrow but stable band at middle

elevations on upper Pacific slope); even so, visual divergence striking.

New

information:

There

is no new information per se; this

proposal is to provide feedback to IOC’s WGAC, which is working to reconcile

all world lists. However, there is relatively new research in the hybrid zone

that doesn't appear to be considered previously in decisions to classify these

taxa as one species or two.

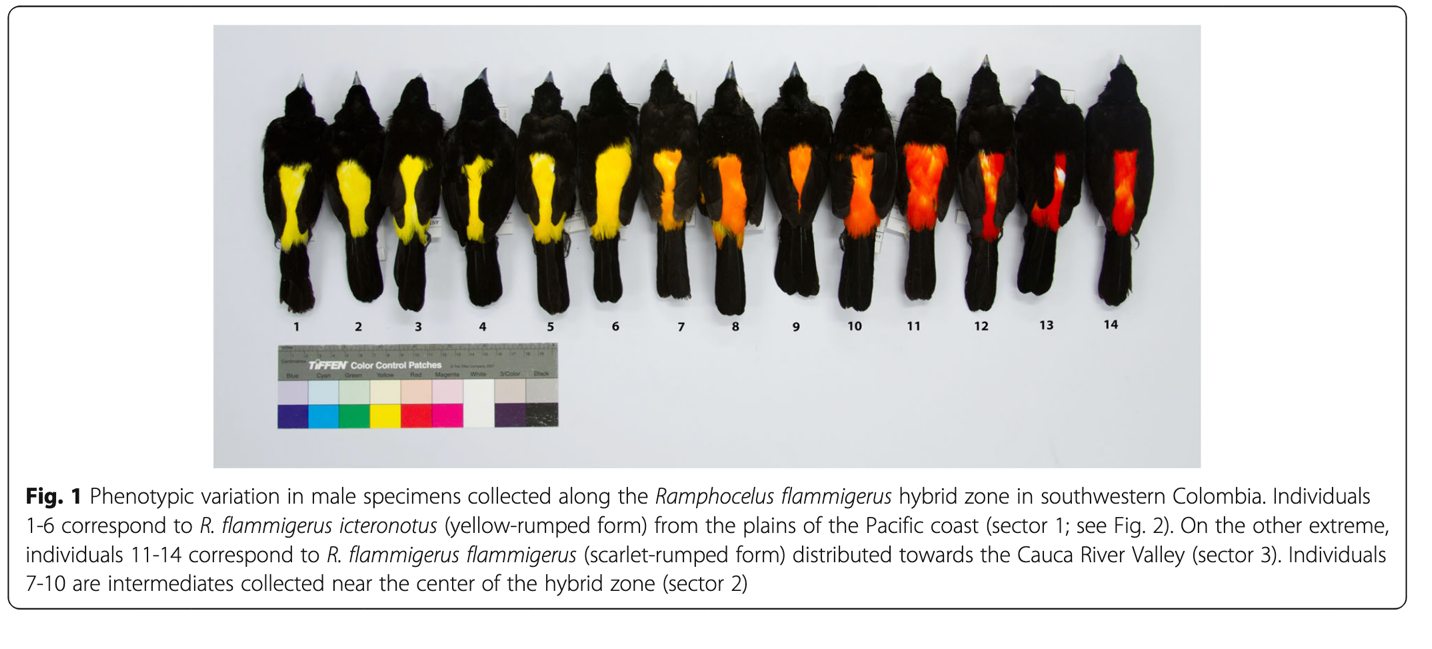

A

hybrid zone between the two taxa in western Colombia has been known for many

years (Chapman 1917). The zone was studied in some detail by Sibley in the

1950’s (Sibley 1958). More recently, Morales-Rozo et

al. (2017) studied the genetics, plumage color, and morphology of birds across

the hybrid zone. The hybrid zone occurs in the Cauca River Valley where the

lower elevation R. f. icteronotus meets the higher elevation R. f.

flammigerus around 800 meters. The hybrid zone occurs along a 140 km

transect and the birds in this area show a gradient from bright yellow to

bright red (see Fig. 1, copied from the paper and inserted below). Morales-Rozo et al. (2017) also mentioned that the two forms meet

and hybridize in additional contact zones further north in the Cordillera

Occidental; however, these areas where not studied at the time of publication.

Morales-Rozo et al. (2017) looked at historical

specimens and collected fresh specimens in 2007-2010. They sequenced cyt b from recent samples as well as from

toe pads of the specimens collected by Sibley. Their genetic analyses included

samples within the hybrid zone as well as samples far from the hybrid zone in

Ecuador and Panama. They also included 6 morphological characters and measured

rump plumage coloration using a spectrophotometer. These phenotypic characters

were defined into three time periods to study the temporal dynamics of the

cline (prior to 1911, 1956-1986, and 2007-2010).

Morales-Rozo et al. (2017) found overall low levels of sequence

divergence. Within Colombia, samples differed on average by only 0.3%, and

samples between Colombia and Panama differed by only 0.4%, but between Colombia

and Ecuador, samples differed by 1.6%. Samples from Ecuador and Colombia could

be separated in their tree, but otherwise no clades were associated with specific

geographic regions or plumage colors. In many cases, individuals with different

rump colors and from different geographic regions had the exact same sequence.

In addition, no genetic structure was detected across the transect. As the

authors stated: “In contrast to multiple studies on hybridization in birds

finding significant mtDNA divergence between populations located away from the

center of hybrid zones and clinal variation in haplotype frequencies across

them, mtDNA variation was not geographically structured in our study system, a

likely consequence of recent divergence of the hybridizing populations or of

high levels of introgression.” In addition, the authors have niche modeling

and demographic data indicating that the two taxa have expanded their range and

come into contact after prior isolation. Although the hybrid zone is often

thought to be the result of recent anthropogenic activity (deforestation and

conversion to crops creating scrub and second growth), the authors’ analyses

show it to be much older than expected – around 6,000 years before present.

However, anthropogenic activity could still have increased the degree of hybridization.

In

contrast to the lack of pattern with the genetic data, the authors did find

clines for the morphological data and for the plumage color data. For each

period of time, the clines for these two character sets where coincident, and

the clines appear to have moved slightly to the east and upwards in elevation.

In addition, the cline is much narrower than expected under a model of neutral

diffusion. Thus, the authors propose that the hybrid zone is a tension zone,

where dispersal of parental forms and selection against hybrids balance each

other out.

There

is actually a talk at next week’s AOS meeting on the same hybrid zone (authors

= Castaño, Cadena, and Uy), this time

using genome-wide SNP data. According to the abstract, the findings look similar

to the mtDNA study: “We found low genetic divergence and genetic structure

across the hybrid zone, and a discordance in the width and cline center between

the genome-wide loci and the plumage clines previously reported. Our results

suggest that there are few intermediate individuals (F1 hybrids) and pure and

backcrossed individuals of the icteronotus subspecies appear to be

distributed across allopatric and sympatric populations.” I will go to the

talk and hopefully chat with the authors, but it looks pretty consistent with

the degree of gene flow found with the mtDNA data. The abstract also mentions

plans to study the other areas of contact mentioned in the Morales-Rozo et al. (2017) study.

Recommendation:

These

two taxa would clearly be recognized as separate species under many other

species concepts, like the phylogenetic species concept, that recognizes past

evolution of characters as defining evolutionary units. In this case, the

plumage differences in both males and females are pretty dramatic and indicate

evolution of characters in allopatry. However, this committee follows the

biological species concept, which downplays the importance of these events in

the face of gene flow, or in the case of allopatric taxa, potentially

significant gene flow. The published genetic study based on mtDNA does indicate

movement of genes across the hybrid zone and the unpublished nuclear data seems

to find a similar pattern. The authors characterize the hybrid zone as a

tension zone; thus, there is some selection against hybrids. However, there

appears to be enough gene flow for this committee to consider them one

biological species. Thus, following this concept, I recommend a NO vote on this

proposal to split these two taxa. The situation is analogous to the relatively

recent lumping by this committee of R. passerinii and R.

costaricensis. These two taxa also differ in the plumage in a similar way

as the taxa under consideration in this proposal.

English

names:

If

we were to vote to split, the English names that are in common use are

Lemon-rumped for R. icteronotus and Flame-rumped for R. flammigerus

sensu stricto.

Literature cited:

Clements, J. F., T. S.

Schulenberg, M. J. Iliff, S. M. Billerman, T. A. Fredericks, J. A. Gerbracht,

D. Lepage, B. L. Sullivan, and C. L. Wood. 2021. The eBird/Clements checklist

of Birds of the World: v2021.

Chapman, F. M. 1917.

The distribution of bird-life in Colombia; a contribution to a biological

survey of South America. Bull. Am. Mus. Nat. Hist. 36:1–729.

Del Hoyo, J., and N. J.

Collar. 2016. HBW and BirdLife International Illustrated Checklist of the Birds

of the World. Volume 2. Lynx Edicions, Barcelona, Spain.

Dickinson, E. C. 2003.

The Howard and Moore Complete Checklist of the Birds of the World. Princeton University Press, Princeton.

Gill F, D. Donsker, and

P. Rasmussen (eds). 2022. IOC World Bird List (v12.1). doi:

10.14344/IOC.ML.12.1.

Hilty, S. L., and W. L.

Brown. 1986. A Guide to the Birds of Colombia. Princeton University Press,

Princeton, New Jersey.

Hilty, S. L. 2021.

Birds of Colombia. Lynx Edicions, Barcelona.

Meyer de Schauensee, R.

1970. A Guide to the Birds of South America. Livingston Publishing Company,

Wynnewood, Pennsylvania.

Morales-Rozo, A., E. A. Tenorio, M. D. Carling, and C. D. Cadena (2017).

Origin and cross-century dynamics of an avian hybrid zone. BMC Evolutionary

Biology 17:257.

Restall, R. L., C.

Rodner, and M. R. Lentino. 2007. Birds of Northern South America: An

Identification Guide. Yale University Press, New Haven, Connecticut.

Ridgely, R. S. and

Greenfield, P. J. 2001. The birds of Ecuador: Status, Distribution, and

Taxonomy. Cornell University Press, Ithaca, New York.

Sibley, C.G., 1958.

Hybridization in some Colombian tanagers, avian genus "Ramphocelus".

Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society 102:448-453.

Sibley, C. G., and B.

L. Monroe, Jr. 1990. Distribution and Taxonomy of the Birds of the World.

Yale University Press, New Haven, Connecticut.

Kevin J. Burns, June

2022

_______________________________________________________________________________

Comments

from Stiles:

NO. Here, I note that the study by Andrea Morales and Daniel Cadena dealt

exclusively with the same transect as used by Sibley to first document the hybridization

between these two forms. However, this is not the only such case of

hybridization over the cordillera Occidental from the Cauca valley into the

Pacific lowlands. I obtained a similar picture of hybridization in a brief

survey transect to the north in Risaralda in 1991 from La Virginia at ca. 800 m

on the río Cauca (all flammigerus) up via Apía

(at ca. 1500 m, where a mixture of all forms, mostly intermediates, was seen)

and on to Pueblo Rico and down to Santa Cecilia at ca. 300 m (here, nearly all

pure icteronotus): in all, ca. 70 birds counted over this route.

Moreover, there is apparently a third and more extensive area of hybridization

exists further north, from Puerto Triunfo at ca. 300 m

on the río Magdalena (all birds seen were icteronotus) up to Medellín

(1800m, where observers there inform me that most birds are intermediates).

From Medellín down southwest to the río Cauca, the country is densely settled,

and various roads reach the river over at least 50 km along the river; at least

at Bolombolo, where I stayed for several days in

1994, all birds seen were flammigerus. Thus, the hybridization of these

two forms is far more widespread than might have been noted previously, and

strongly favors continuing to maintain them as conspecific.”

Comments from

Remsen: “NO. That

the contact zone consists of a hybrid swarms with mostly intermediate birds

indicates absence of assortative mating – these two populations treat each

other as “same” when it comes to mat choice, so, in my opinion, why shouldn’t we? The cline in variation between the two is

best seen in the rump color data in Morales-Rozo et

al.’s Fig. 6D (based on Sibley’s 1956 samples).

The hybrid swarm that comprised the contact zone is sufficient reason to

treat them as conspecific.”

Comments from Claramunt: “NO. The situation could be explained by a color polymorphism,

geographically structured, but within a single species. The lack of genetic

differentiation and the multiple instances of hybridization and introgression

suggest a single species.”

Comments from Robbins: “NO, for reasons presented in the

proposal, plus those comments by Gary Stiles stating that the zone of

intergradation is broader (“far more extensive”) than what is presented in the

literature.”

Comments

from Areta:

“NO. Extensive hybridization from several localities across a broad front and

across a considerable distance, coupled to little genetic differentiation (in

mtDNA) away of the area of the hybridization, plus minor plumage differences

(yellow vs. red carotenoid-based plumages), no association of geographic origin

to mtDNA clades, and long-term persistence of this situation indicates that

these two are behaving as a single unit in places in which they meet. It might

also be the case that the "orange" birds are equally palatable to

"yellow" and "red" birds, and thus even in the face of

selective disadvantage, there is gene flow between the extreme populations. If

reinforcement will happen or not we do not know, but so far, I don´t see compelling

evidence to recognize them as separate species. The widespread hybridization

across geography and the wide hybrid cline that was studied in detail indicates

that flammigerus and icteronotus are not behaving as separate

species. I would contend that given the rampant hybridization, no species

concept would have an easy time supporting their recognition as different

species.”

Comments

from Lane:

“NO. The presence of multiple areas where there

appears to be extensive interbreeding between yellow and scarlet rumped

populations, evidence supporting their separation is overwhelmed by that

supporting continuing to consider them a single biological species.”

Comments from Bonaccorso: “NO. Even if the hybrid zone is a

“tension zone” there is enough geneflow for genes to intergrade from one form

to the other and maintain a perfect cline. I agree with Van´s comment: “these

two populations treat each other as “same” when it comes to mate choice, so, in

my opinion, why shouldn’t we?”

Comments from Zimmer: “NO,

for all of the reasons elucidated in the proposal. As different as the two taxa are in plumage

at their extremes, the existence of a rather broad hybrid swarm in the contact

zone would seem to be sufficient evidence that the two taxa are not

discriminating between one another to the extent one would expect if, indeed,

they represented distinct biological species.”

Comments from Pacheco: “NO. Because there is no genetic differentiation and the

hybridization area is more extensive (Gary) than previously admitted.”