Proposal (950) to South

American Classification Committee

Note from Remsen: This

is slightly modified version of the proposal submitted to NACC by Oscar.

Treat Chlorothraupis

frenata as a separate species from

Carmiol’s Tanager C. carmioli

Description of the problem:

Chlorothraupis carmioli (Lawrence 1868)

is a polytypic species broadly comprised of two subspecies groups; a northern

group of three subspecies (carmioli, magnirostris Griscom 1927, and lutescens Griscom 1927) found in lowland

and foothill tropical forests from Honduras to extreme northwestern Colombia,

and a South American subspecies frenata

von Berlepsch 1907 found in the eastern foothills of the Andes from southern

Colombia to central Bolivia (Hilty 2022). Although these two subspecies groups

are highly disjunct, the intervening regions are occupied by two congenerics; C. olivacea (Cassin 1860) of the

lowlands and foothills of western Colombia and northwestern Ecuador (the Chocó)

and just reaching far eastern Panama, and C.

stolzmanni (von Berlepsch & Taczanowski 1884) of the same region but

replacing olivacea at higher

elevations and not reaching Panama (Hilty 2020a,b). Within Central America, the

two southern subspecies are somewhat more yellow and larger-billed in western

Panama (magnirostris) and much more

yellow and smaller-billed in eastern Panama (lutescens), while nominate carmioli

is found from Costa Rica north (Griscom 1927). For simplicity, I’ll refer to

these three northern subspecies as the “carmioli”

group throughout this proposal.

The current species-level treatment is largely

unchanged since each of the taxa was described. The two taxa first described, C. olivacea and C. carmioli, were each

considered species by the describing authors, and most subsequent authors (e.g.

Dickinson 2003). The ranges of the two approach each other in eastern Panama

and apparently don’t show signs of hybridization. Ridgely and Gwynne (1989),

specimen data on VertNet, and occurrence records in eBird all indicate that C. olivacea

is found on the eastern Darién mountains of Cerro Sapo,

Pirre, Quía, and Jaqué, but

is replaced on Cerro Tacarcuna by C. carmioli. C. carmioli frenata was

described as a subspecies of carmioli

by von Berlepsch. von Berlepsch’s (1907) reasoning for maintaining frenata as a subspecies of carmioli is worth reproducing here in

full:

“It is a curious fact that the Chlorothraupis of South-eastern Peru has its nearest ally in a

species which, as far as we know, is restricted to the forest-region of Costa

Rica. In fact, the resemblance between Costa Rican and Peruvian examples of

this Chlorothraupis is so great that

Messrs. Sclater and Salvin have not attempted to separate them.

“In the

meantime, having (through the kindness of the Hon. W. Rothschild) had an

opportunity of comparing five adult birds, collected by Mr. Underwood in Costa

Rica, with my specimens from Marcapata, South-east Peru, collected by Mr. O.

Garlepp, I have detected some small though apparently constant characters, by

which the Peruvian birds may well be distinguished.

“In the

latter the lores and the small feathers of the frontal line near the nostrils

are yellowish (purer and brighter yellow in the younger and more

greenish-yellow in the adult specimens), while in the Costa Rican birds these

parts are of the same dark olive-green as the upper part of the head.

“Further,

the general coloration of the upper and under parts of the body of the Peruvian

birds is of a clearer and purer green, while the Costa Rican birds show a

rather more oily or brownish tint in the plumage. The alar margin and the under

wing-coverts in the Peruvian specimens are of a clearer or more a

yellowish-green colour. The tail is of a rather

brighter green or less blackish.

“As a

rule the wings and the tail in the Peruvian birds appear to be a little

shorter.”

The yellow color of the lores is the main

plumage character that separates C. olivacea

and C. carmioli, although the differences in that comparison are much more

extreme, and give the former species its English name, Lemon-spectacled

Tanager. Many authors (e.g. AOU 1983,

1998, Isler & Isler 1987) gave C.

carmioli the English name Olive

Tanager, but the NACC (following Meyer de Schauensee 1970, Dickinson 2003, and

others) changed the English name to Carmiol’s Tanager to avoid confusion with C. olivacea (Banks et al. 2008). The

SACC also adopted this change and recommended that “Olive Tanager” be

restricted to classifications that treat C.

olivacea and C. carmioli as conspecific (Remsen et al.

2022), as the former has priority and would keep a match between the English

and Latin names. However, I am unable to find any authors that treat these two

species as conspecific, although I could be overlooking older references.

Zimmer (1947) summarized the plumage differences

between the carmioli group, frenata, and olivacea better than I am able, and it appears little has been done

on morphological differences in the complex since:

“The wide separation of the range of this form [=frenata] from that of the other members of the species is curious,

especially in view of the occupation of the intervening terrain by C. olivacea and C. stolzmanni. Both of these last-mentioned forms appear to be

specifically distinct from carmioli

with which no intergradation of characters has been discovered at any point.

The three species are undoubtedly quite closely related. The pale lores of frenata might be considered as

suggesting the bright yellow lores of olivacea,

although the equally conspicuous yellow eye ring of olivacea is not similarly suggested, and the resemblance in the

color of the lores is not very striking, quite aside from the fact that olivacea and carmioli lutescens occur very near to each other in eastern

Panamá.”

Despite the plumage similarity between the two

taxa, some recent authors have elevated frenata

to the species rank (Ridgely and Greenfield 2001, Restall et al. 2006, del Hoyo

and Collar 2016). Ridgely and Greenfield (2001) treated frenata as a species based on descriptions of the voice and the

disjunct distribution, while del Hoyo and Collar (2016) did the same, with the

following reasoning:

“Often

treated as conspecific with C. carmioli,

the two being morphologically very similar, but quite easily separated by their

different vocalizations, including song; further investigation desirable.

Monotypic.”

The IOC elevated frenata to species rank, and gave C. frenata the English name Olive Tanager, and left C. carmioli with the English name of

Carmiol’s Tanager.

New information:

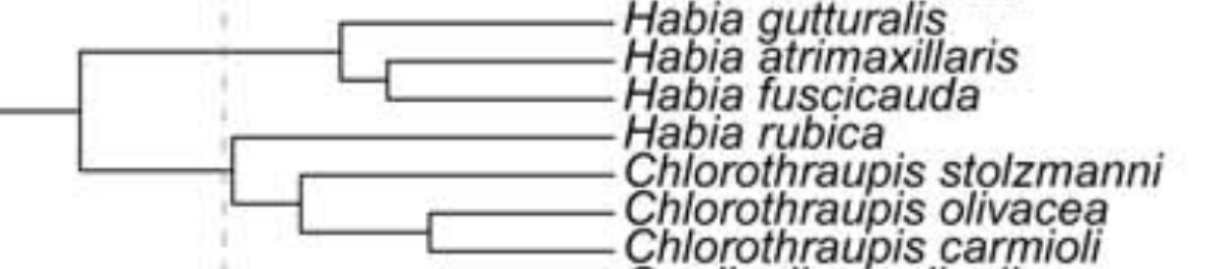

Barker et al. (2015) sampled the three species

of Chlorothraupis and found that olivacea and carmioli were sisters, and that the three Chlorothraupis were embedded within Habia (separate proposal needed for generic limits). The sample of carmioli was obtained from Burns (1997)

and is a specimen of frenata from San

Martín, Peru (LSUMZ B-5510). Klicka et al. (2007) recovered the same topology,

using a sample of frenata from

Ecuador. No other genetic data appear to be published for this complex, and

none from nominate carmioli or the

other Central American subspecies. Both studies were based on a few

mitochondrial and nuclear loci. A screenshot of the Barker et al. (2015)

phylogeny is below.

Van Remsen has graciously photographed a series

of specimens of magnirostris, frenata, and olivacea housed at the LSUMZ. Photos are below. In both photos, the

taxa shown are (top to bottom): magnirostris,

two olivacea, and frenata. Note the more extensive yellow

spectacles and darker coloration of olivacea,

and the slightly more yellow lores of frenata.

Although much of the early work on the complex

highlighted the minor, albeit consistent, plumage differences, the main

differences between the two clades is in vocalizations. However, no

publications have quantified these differences as far as I am aware, and this

group was not included in Boesman’s Ornithological

Notes. A detailed description of the vocalizations is given in Hilty (2022):

“Dawn

song a rapid stream of mostly short notes, some grating or wheezy, some

musical, and typically given rapidly in groups of 3–8, then abruptly switching

to another type of note, entire sequence often lasting up to several minutes;

some song sequences consist of clear whistled notes much like those of Northern

Cardinal (Cardinalis cardinalis). Can

be rather noisy when foraging, uttering variety of mostly short, high, thin

notes, including chay, a squeaky eep, a churring wrsst, and abrupt

chut, squeezed chee and metallic whit; also a slightly buzzy seeet or seee-seeee and

staccato tik in bursts when about to

fly; in alarm a scratchy nyaaah

or cheeyah.

“Songs

and other vocalizations of frenata

are rather unlike those of the Central American subspecies. In southeastern

Peru, frenata makes an excited, rapid

rolling ki’r’r’rup-ki’r’r’rup-ki’r’r’rup-ki’r’r’rup-ki’r’r’rup..., sometimes up to ca. 8 notes in the

series with squealing, frantic quality, and often repeated over and over at

short intervals. At times song more varied, with other high or squeaky notes

inserted into the long series, e.g. ki’r’r’rup-ki’r’r’rup-ki’r’r’rup-éé-kir’r’r’r-éé-kir’r’r’r, squik-Skeek-Skeek–Skeek-kir’r’r-kir’r’r...

and so on for up to 30 seconds or more; also transcribed as a grating kettup or keetup. A

somewhat more melodic song (context uncertain) is a series of several similar

notes, then a series of different notes, and so on: e.g., chow-chow-chow-chow-chi-chi-chi-chow, chow,

chow, whi-chow, whi-chow, wheeup, wheeup, wheeup, wheeup, tic-chow tic-chow, tic-chow, tic-chow, tic-chow, tic-tic-tic-tic-ch-ch-ch-ch..., for 10–25

seconds.”

The songs of the carmioli group and frenata are

clearly analogous; both are run-on series of very cardinalid-like whistled

notes. The primary difference, to my ear, between the songs of the two groups

is the much more rapid delivery (note pace) of the songs of the carmioli group. Although Hilty (2022)

mentioned that frenata gives a more

rolling “ki’r’r’rup”

song, this seems to be variable, and many (perhaps most) individuals of frenata give more clear whistled songs,

as noted by Schulenberg et al. (2007). Overall, note pace seems to be fairly

consistent across the distribution of each group.

Songs of the carmioli

group:

https://macaulaylibrary.org/asset/25644

https://macaulaylibrary.org/asset/201575871

versus these of frenata:

https://macaulaylibrary.org/asset/101818 (this one contains more “ki’r’r’rup” notes)

https://macaulaylibrary.org/asset/224539281

https://macaulaylibrary.org/asset/238023

Both taxa give a wide variety of other calls

(see text from Hilty 2022 above), but differences between the two groups seem

primarily to be a lower-pitched scolding call in frenata.

carmioli group:

https://macaulaylibrary.org/asset/165887

https://macaulaylibrary.org/asset/203938651

https://macaulaylibrary.org/asset/211144

frenata:

https://macaulaylibrary.org/asset/138819

For reference, the song of C. olivacea is more like that of frenata in terms of pace:

https://macaulaylibrary.org/asset/149272491

Effect on SACC area:

Splitting frenata

from the carmioli group would add one

new species to the SACC checklist area.

Recommendation:

I recommend a YES vote on splitting frenata from the carmioli group. C. carmioli

would retain magnirostris and lutescens as subspecies. My only

hesitation in splitting these taxa is a lack of genetic data for carmioli, lutescens, or magnirostris.

However, given the highly disjunct distribution from frenata, plus intervening congenerics, I would be very surprised if

these two groups did not show some genetic divergence. The plumage differences

are minor but consistent, and parallel with other species-level differences in

the group (albeit to a lesser degree). Most convincingly, the vocalizations are

consistently different, and seem to not vary considerably across the

distribution of each group (just in my cursory listening of recording, an

analysis is certainly needed!), despite the wide range of different

vocalizations given by these taxa.

Please vote on the following:

1) elevate frenata to species rank

If frenata

is elevated to species rank, new English names will be required. Clement’s / Birds of the World (2022) uses Carmiol’s

Tanager for the C. carmioli group and

Yellow-lored Tanager for C. carmioli

frenata. Although Carmiol’s Tanager has long been used for the combined

species, no other names have been used for the northern group and keeping

Carmiol’s would maintain a match with the species epithet. The two groups have

roughly comparable range sizes, likely a slightly larger distribution in frenata, so keeping Carmiol’s Tanager

with C. carmioli does go against

NACC/SACC guidelines. However, it does seem like an option to me in this case.

Olive Tanager has been used for C.

carmioli s.l. (see citations above) but the NACC changed the name from

Olive Tanager to Carmiol’s Tanager in 2008 specifically to avoid confusion with

C. olivacea (Lemon-spectacled Tanager),

so applying that name to C. carmioli

s.s. seems like a poor choice. The IOC, in elevating frenata to species rank, gave it the name Olive Tanager (see

above), but that, too, seems like a poor choice that only adds to the confusion

regarding the application of the name “Olive Tanager”. If Carmiol’s is

unacceptable to the committee as the English name for C. carmioli s.s., a separate proposal will be needed to address the

English name of that taxon. The namesake of carmioli

is Francisco Carmiol, a German immigrant to Costa

Rica who worked as a bird collector for the Smithsonian and collected the type

specimen of carmioli (Lawrence 1868,

Birds of the World 2022). Francisco was the son of the bird collector Julián Carmiol, for whom Vireo

carmioli is named (Birds of the World 2022), but little else appears to be

published about the two Carmiols. Alternatively,

Yellowish Tanager or Yellow-olive Tanager seem like decent options for C. carmioli s.s., would highlight the

more yellow coloration of at least some populations of the carmioli group, and would

be parallel to Yellow-lored and Lemon-spectacled Tanagers. Olive-green Tanager

is occupied by Orthogonys chloricterus.

Note from Remsen: If

the proposal passes, then we will need a separate proposal on English names,

but feel free to open the discussion on this in your Comments.

Literature Cited:

AOU. 1983.

Check-list of North American birds. 6th edition. American Ornithologists’

Union.

AOU. 1998.

Check-list of North American birds. 7th edition. American Ornithologists’

Union.

Banks, R. C., R. T. Chesser, C. Cicero, J. L. Dunn, A. W. Kratter, P. C.

Rasmussen, J. V. Remsen, Jr., J. A. Rising, and D. F. Stotz. 2008.

Forty-ninth supplement to the American Ornithologists' Union Check–list

of North American Birds. Auk 125:

758–768.

Barker, F. K, K. J. Burns, J. Klicka, S. M. Lanyon, and I. J. Lovette.

2015. New insights into New World biogeography: An integrated view from the

phylogeny of blackbirds, cardinals, sparrows, tanagers, warblers, and allies.

The Auk 132(2): 333-348. http://dx.doi.org/10.1642/AUK-14-110.1

von Berlepsch, H. G. 1907. Descriptions of new species and subspecies of

Neotropical birds. Proceedings of the IVth

International Ornithological Congress pp. 347-371.

Birds of the World. 2022. Edited by S. M. Billerman, B. K. Keeney, P. G.

Rodewald, and T. S. Schulenberg. Cornell Laboratory of Ornithology, Ithaca, NY,

USA. https://birdsoftheworld.org/bow/home

Burns, K. J. 1997. Molecular systematics of tanagers (Thraupinae):

evolution and biogeography of a diverse radiation of Neotropical birds.

Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 8(3): 334-348.

https://doi.org/10.1006/mpev.1997.0430

Dickinson, E. C.

(Ed.) 2003. The Howard & Moore

Complete Checklist of the Birds of the World, 3rd edition, Christopher

Helm, London.

Griscom, L. 1927. Undescribed or little-known birds from Panama.

American Museum Novitates 280: 1-19.

Hellmayr, C. E. 1935. Catalogue of birds of the Americas, part VIII.

Field Museum of Natural History Zoological Series Vol. XIII. Chicago, USA.

Hilty, S. 2020a. Lemon-spectacled Tanager (Chlorothraupis olivacea), version 1.0. In Birds of the World (J.

del Hoyo, A. Elliott, J. Sargatal, D. A. Christie, and E. de Juana, Editors).

Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, NY, USA.

https://doi.org/10.2173/bow.lestan.01

Hilty, S. 2020b. Ochre-breasted Tanager (Chlorothraupis stolzmanni), version 1.0. In Birds of the World (J.

del Hoyo, A. Elliott, J. Sargatal, D. A. Christie, and E. de Juana, Editors).

Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, NY, USA.

https://doi.org/10.2173/bow.ocbtan1.01

Hilty, S. 2022. Carmiol's Tanager (Chlorothraupis

carmioli), version 1.1. In Birds of the World (N. D. Sly, Editor). Cornell

Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, NY, USA. https://doi.org/10.2173/bow.olitan1.01.1

del Hoyo, J., and N. J. Collar. 2016. HBW and BirdLife International

Illustrated Checklist of the Birds of the World. Volume 2: Passerines. Lynx

Edicions, Barcelona, Spain.

Isler, M., and P. Isler. 1987. The Tanagers, Natural History,

Distribution, and Identification. Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C.

Klicka, J., K. Burns, and G. M. Spellman. 2007. Defining a monophyletic

Cardinalini: A molecular perspective. Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 45(3):

1014-1032. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ympev.2007.07.006

Lawrence, G. N. 1868. III.—A Catalogue of the Birds found in Costa Rica.

Annals of The Lyceum of Natural History of New York, 9: 86-149.

Meyer de Schauensee, R. 1970. A guide to the birds of South America.

Livingston Publishing Co., Wynnewood, Pennsylvania.

Peters, J. L. 1968. Check-list of birds of the world. Vol. XIV. (R. A.

Paynter, Ed.). Museum of Comparative Zoology. Cambridge, Mass.

Remsen, J. V., Jr., J. I. Areta, E. Bonaccorso, S. Claramunt, A.

Jaramillo, D. F. Lane, J. F. Pacheco, M. B. Robbins, F. G. Stiles, and K. J.

Zimmer. Version 2022. A classification of the bird species of South America.

American Ornithological Society.

http://www.museum.lsu.edu/~Remsen/SACCBaseline.htm

Restall, R., C.

Rodner, and M. Lentino. Birds of northern South America, an identification

guide. Vol. 1. Yale University Press, New Haven, CT, USA.

Ridgely, R. S.,

and J. A. Gwynne. 1989. Birds of Panama. 2nd Ed. Princeton

University Press, Princeton, NJ, USA.

Ridgely, R. S., and P. J. Greenfield. 2001. The Birds of Ecuador.

Volumes 1–2. Cornell University Press, Ithaca, NY, USA.

Ridgway, R. 1902. The birds of North and Middle America. Part II.

Bulletin of the United States National Museum. No. 50.

Schulenberg, T. S., D. F. Stotz, D. F. Lane, J. P. O’Neill, and T. A.

Parker III. 2007. Birds of Peru, revised and updated edition. Princeton

University Press, Princeton, NJ, USA.

Wetmore, A., R. F. Pasquier, and S. L. Olson. 1984. The Birds of the

Republic of Panama. Part 4. Smithsonian Miscellaneous Collections, vol. 150,

Washington, D.C.

Zimmer, J. T. 1947. Studies of Peruvian Birds No. 51. The genera Chlorothraupis, Creurgops, Eucometis,

Trichothraupis, Nemosia, Hemithraupis, and Thlypopsis, with additional notes on Piranga. American Museum Novitates 1345: 1-23.

Oscar Johnson, July 2022

March 2023 update from Oscar Johnson:

“he details on the

following study were overlooked in an earlier version of this proposal.

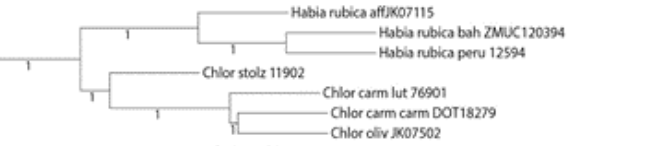

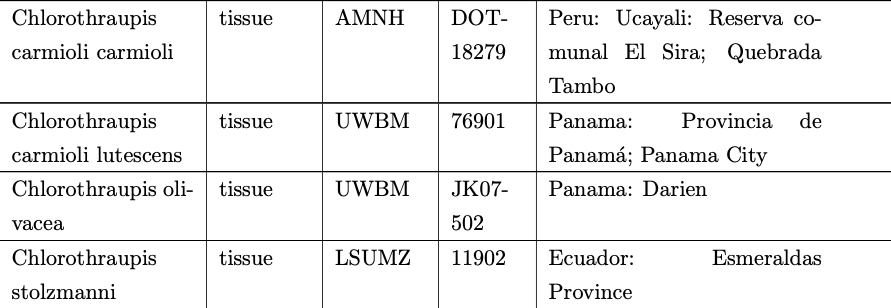

A recent master’s

thesis (Scott 2022), focused on the Cardinalidae, sampled all species of Chlorothraupis,

including one sample from Peru (frenata) and one from Panama (lutescens)

and sequenced 5,022 UCE loci. Concatenated and coalescent gene tree methods

both recovered the same topology, which shows Chlorothraupis carmioli

is paraphyletic. I have included the portion of the tree below that includes

the Chlorothraupis taxa. This is the summary of the “multispecies

coalescent gene trees produced by IQ-tree and summarized using ASTRAL”, which

includes branch lengths (unlike some of the other methods used in the thesis),

and branch numbers refer to posterior probabilities.

Note that “Chlor carm carm”, i.e. “carmioli”,

is mislabeled and in fact refers to frenata based on sampling locality. The

sampling table is included below for reference.

Updated recommendation:

I recommend a YES vote on splitting frenata from the carmioli group. C. carmioli

would retain magnirostris and lutescens as subspecies. The nuclear

data from Scott (2022) show that the current definition of C. carmioli

is paraphyletic, with C. c. frenata sister to C. olivacea,

and with fairly long branches separating the three groups. In addition, the

plumage differences are minor but consistent, and parallel with other

species-level differences in the group (albeit to a lesser degree). The

vocalizations are also consistently different, and seem to not vary

considerably across the distribution of each group (just in my cursory

listening of recording, an analysis is certainly needed!), despite the wide

range of different vocalizations given by these taxa.

_______________________________________________________________________________

Comments from Remsen: “YES.

Although one can always demand more data, I think the vocal differences

outlined in the proposal are sufficient grounds for treating them as separate

species. As noted back in 1989 by

Ridgely & Tudor, the highly disjunct range is suspicious, and even then,

anecdotal information on voice suggested a potential split. We have accumulated enough recordings now

that confirm those initial findings and places burden-of-proof in my opinion on

treating them as conspecific. I think

the only valid basis for rejecting the proposal might be absence of playback

trials.

“There is another

reason for conservatively treating them as separate species. As far as I can tell, the phylogenies

published so far have not sampled both the carmioli group and the frenata

groups. In both published analyses, C.

carmioli is represented by the same sample of frenata from N. Peru,

as if that sufficiently characterizes the genome of a species with disjunct

populations separated by a thousand kilometers and on opposite sides of major

biogeographic boundaries. This is yet

another example of failing to appreciate the importance of broad taxon-sampling

in phylogenetic analysis. How do we even

know that the carmioli group is monophyletic? In fact, that two other Chlorothraupis

occupy the intervening region in similar habitats makes me wonder if there

isn’t a leap-frog pattern going on here, with either stolzmanni or olivacea

or both being more closely related to one of the carmioli groups than C.

(c.) frenata and C. c. carmioli are to each

other. Seems like a long-shot, but it is

sufficient for me to object to a conspecific treatment without genetic data

confirming the monophyly of our current C. carmioli. I’d also like to hear from Kevin Burns how

much confidence he has in that topology from 2007.

“As for the plumage

similarities, such similarities are roughly comparable to those between some

species in genera closely related to Chlorothraupis: some Habia

species, some Piranga species (e.g. hepatica and rubra,

and definitely between the eventually to-be-delimited species within hepatica),

and, most notably, the other two Chlorothraupis species, which are

treated as separate species already.

Check out Plate 32 in HBW Vol. 16 to see what I mean. Frenata and carmioli are more

similar to each other than either is to olivacea or stolzmanni,

but not by much, especially if you allow for a little Gloger’s Rule darkening

of the latter two in those more humid regions.

Take away the eyering of olivacea and presto, suddenly it no

longer stands out.

“As for English

names, “Olive Tanager” is clearly DOA because of C. olivacea and

inconsistency in what “Olive Tanager” applies to. Let’s bury that one forever. I also think we should consider changing the

last name from Tanager to Chlorothraupis.

We have an opportunity to de-Tanager another non-thraupid genus, with

Spindalis and Chlorospingus providing precedents with which the world seems

comfortable. As an English name,

Chlorothraupis is no more intractable than Chlorospingus (or Hemispingus),

although unfortunately it retains the “thraupis” part

that still connotes a tanager. Although

their close relatives in the Cardinalidae, Habia and Piranga,

will likely retain “Tanager” in their name forever, at least using

Chlorothraupis will help remind us of the family-level change (gee, thanks,

Kevin). None of the four species occurs

in an English-first country. and none is a particular familiar widespread bird,

so this minimizes the impact of the instability caused by such a change.”

Comments

from Robbins:

“I vote YES for recognizing Chlorothraupis frenata

as a species. Although it would be more

informative to have a complete genetic data set for all taxa in Chlorothraupis,

the combination of the disjunct distribution (with intervening species), vocal

differences, and consistent plumage characters (in a complex where plumage

morphology is highly conserved) supports recognition of frenata as a

species.”

Comments from Claramunt: “NO. The plumage differences are

so subtle and vocalizations so varied and complex that this proposal requires a

full analysis of geographic variation examining potential clines and

intergradation. Genetic data for at least the two major groups would be

desirable too.”

Comments

from Areta:

“NO. I would normally vote unambiguously against splits based on these type of

data, but this case seems peculiar in that two Chlorothraupis species are geographically sandwiched by the two

subspecies groups of C. carmioli,

which differ subtly but diagnosably in plumage and (apparently) also in

vocalizations (mostly in the speed of delivery of the songs and in the pitch of

the scold [it also may be longer and more burry, with longer time between

inflections in frenata]). As often is

the case, plumage differences have been well substantiated, whereas differences

in the vocalizations have been cursorily described without rigorous analyses

(as underscored by Oscar). The southern C.

carmioli frenata has itself an apparently fragmented distribution that

extends across several well-known biogeographic breaks. All the evidence points

towards species status of frenata.

However, rigorous published analyses based on comprehensive datasets are

lacking, and given the structural similarities in the songs and calls and the

reduced plumage differences, one may argue that the widely allopatric frenata and carmioli groups are recently diverged. I will therefore vote NO

until the evidence is properly analyzed and put in perspective, with thorough

characterizations of the vocalizations and, hopefully, also with genetic data.”

Comments

from Stiles:

“YES for recognizing C. frenata as a species separate from C.

carmioli; this is supported by both vocalizations and plumage, albeit in

the latter, the difference is more subtle. In any case, given the existence of

two species in the long Interval between carmioli and frenata, neither

of which are known to undertake extensive migrations, I find the suggestion of

an independent colonization of carmioli so far to the south to be

decidedly far-fetched. Of the two intervening species, I am moderately familiar

with stolzmanni, which is distinctive in its more buffy-brownish color

below and its exceedingly raucous vocalizations, as well as its grayish iris

(in the 3 specimens I have collected) and agree that those of olivacea definitely

sound different from those of carmioli, which I have heard often in

Costa Rica.”

Comments

from Lane:

“YES. I am swayed by Oscar's arguments here. The

voices of the two groups (carmioli and frenata) are not

super-distinctive to my ear, but they are different enough (and about as

different as those of the other two congeners) to make me think that they

should be considered distinct, and the biogeography makes the conspecificity of

the two dubious at best. For English names, why must we just consider

plumage-based names? "Foothill Tanager" would outline the typical

distribution C. frenata well, or something like "Growling

Tanager" based on the calls one hears regularly.”

Comments

from Bonaccorso:

“NO. The data are fairly scant. Plumage differences

are within those found among conspecifics. There are not enough vocal data to

decide objectively, and molecular data are based on one sample per subspecies

for the subspecies that are represented in the phylogeny.”

Comments from Zimmer: “YES. With a nod to the concerns expressed by

Santiago and Nacho, count me in the camp that thinks the vocal differences are

different enough, even without a rigorous quantitative analysis across all

populations. Coming from the perspective

of someone who was very familiar with the Central American carmioli-group from Panama and Costa Rica, long before encountering

frenata, I was struck on my first and

all subsequent encounters with the latter, by the vocal distinctions, more so

in the calls than in the songs, which, at least in my experience, are heard

from these birds far more than are the songs.

The way that these roving gangs of tanagers leapfrog through the dark

forest understory, maintaining contact with one another through their

continuously delivered, varied, and sometimes, even explosive vocalizations,

would suggest to me that any stereotypical vocal differences between these taxa

are of magnified importance with respective to any potential or actual gene

flow, and are much more likely to be indicators of such than are the relatively

subtle plumage differences. As Van

points out, these plumage distinctions, although subtle, are on par with those

between some species-pairs of Habia (which,

in many respects, are similar to Chlorothraupis

behaviorally, and in the breadth of their vocal repertoires, as well as in

plumage and overall morphology), so the plumage similarities between carmioli (northern group) and frenata don’t really bother me. Also, as pointed out by Oscar, and reiterated

by others on the committee, the nature of the range disjunction between the

two, with two recognized (as distinct) congeners occupying the gap, requires

some mental gymnastics to square with biogeography. I’ll hold off on diving into English names in

any depth until we have a separate proposal, but I am partial to retaining

“Carmiol’s” as the name for the CA group, and I would agree with comments

expressed to the effect that using “Olive” is a non-starter.”

Comments from Pacheco: “YES. Influenced mainly by

Kevin's last comments, in which he highlights the capricious disjunction of

these two taxa.”

Additional comments from Claramunt: “I change

my vote to YES. On a second read of the proposal and inspection of images of

nominate carmioli and frenata, I realized that the plumage

differences are clear and consistent. In particular, the combination of a

yellowish face and a contrasting black bill give frenata a very distinct

look. I now think that this is yet another case in which, under the polytypic

species concepts, similar-looking taxa were lumped without any evidence of

shared ancestry or reproductive compatibility, distorting reality and producing

an artifactual biogeographic pattern.”

Comments

subsequent to 1 March 2023 update