Proposal (956) to South

American Classification Committee

Species

limits and generic placement of Phaeomyias

murina

Our current SACC note reads:

“20. Ridgely

& Tudor (1994) noted that vocal differences suggest that Phaeomyias

murina might consist of more than one species. Ridgely & Greenfield

(2001) considered the subspecies tumbezana (with inflava and maranonica)

of southwestern Ecuador and northwestern Peru to represent a separate species

based on differences in vocalizations.

Rheindt et al. (2008c) found genetic evidence consistent with two

species, and Zucker et al. (2016) found additional evidence for multiple

species within P. murina. SACC proposal badly

needed."

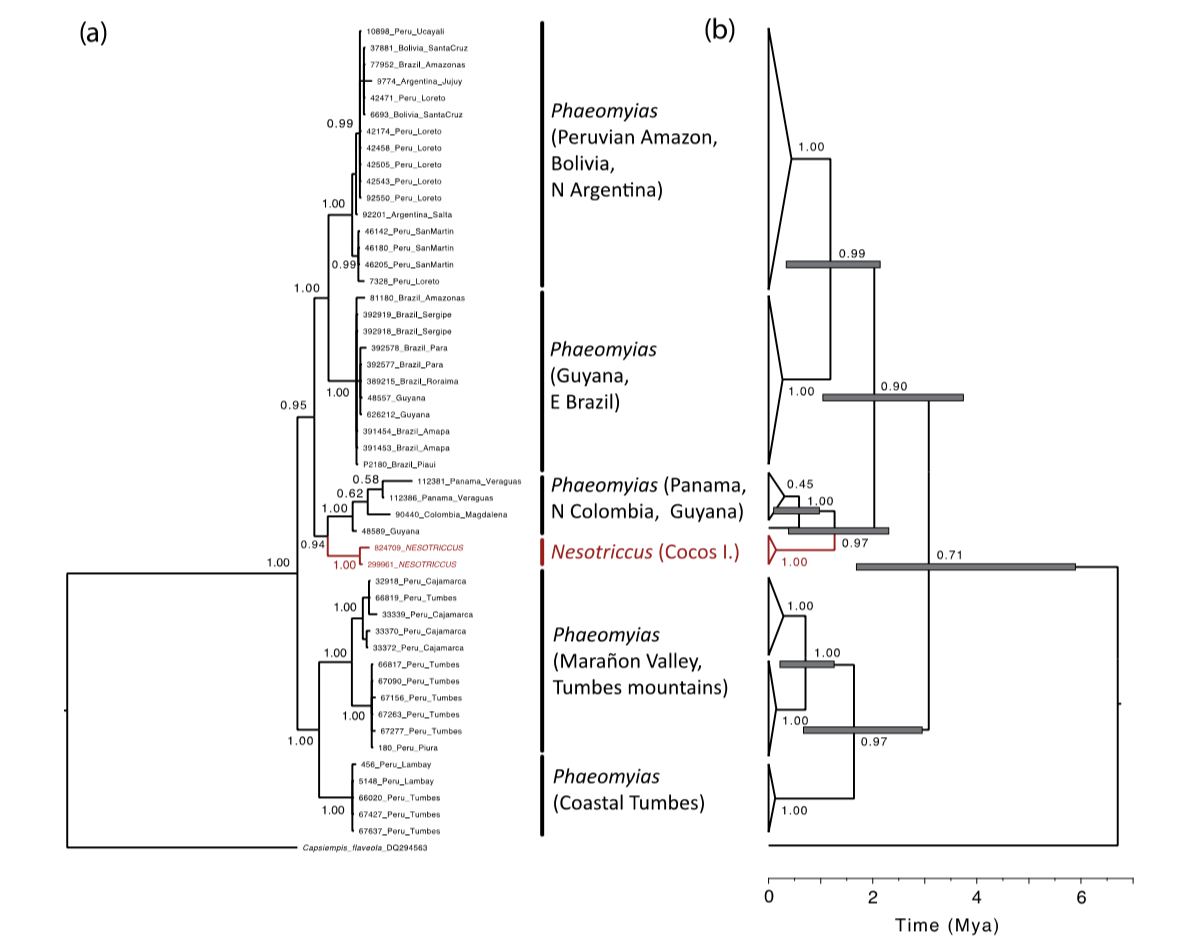

Zucker et al. (2016) provided key material to discuss

species limits in Phaeomyias murina.

What they found is that the Cocos Flycatcher, historically placed in the genus Nesotriccus, is embedded

within Phaeomyias

and that the latter includes 4-5 distinct clades, which might merit species

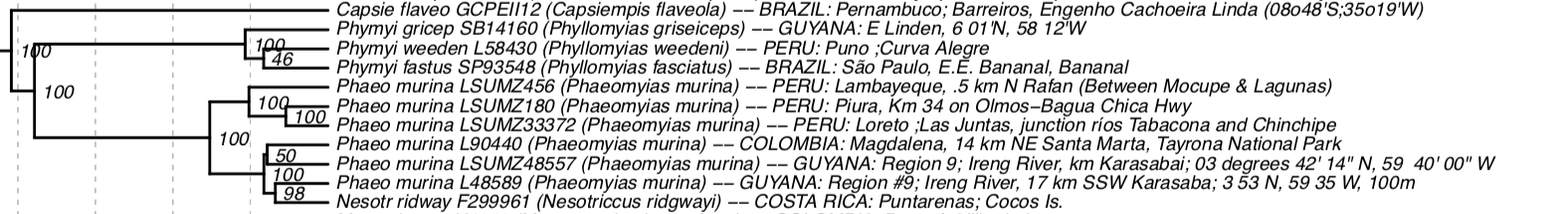

status. Harvey et al. (2020) recovered a similar phylogenetic structure. Lanyon

(1984) had already shown that Phaeomyias

and Nesotriccus

were closely related, and Rheindt et al. (2008) also provided phylogenetic

information to begin to unfurl this riddle. This is a good example of why “express”

splits should not be done even if obvious and why deep studies are needed:

there are surprises hidden everywhere.

As I see it, we have the following options:

1)

Split P.

tumbezana (with ssp. inflava): tumbezana/inflava and maranonica

are narrowly parapatric, are deeply diverged and differ in vocalizations. Zucker

et al. (2016: 300) wrote:

"Lowland tumbezana and montane populations

matching maranonica in plumage,

voice, and mitochondrial DNA occur within about 10 km of each other on the

lower slopes of the western Andes, where they appear to segregate by habitat

and elevation (Angulo et al., 2012; Schmitt et al., 2013; F. Angulo P., D.

Lane, pers. comm.). Vocal, morphological, and genetic data divergence between tumbezana/inflava and maranonica (including montane Tumbes

populations), combined with their nearly sympatric distributions, suggest the

two merit recognition as separate species. Further work is needed to ascertain

if interbreeding or introgression occurs in this region."

2) Split P.

maranonica: keeping the splits 1 and 2 under a single species P. tumbezana would be

another option, but this is not recommended given the vocal differences (see

Schulenberg et al. 2007), the relatively deep genetic break and the near

parapatry of these taxa.

3) Split P.

incomta (with ssp. eremonoma):

note that the paper by Kroodsma et al. (1987) on the

vocalizations of ridgwayi,

coupled to its divergent morphology (see Sherry 1985, cited in Sherry 1986),

and level of genetic divergence argue against the lump of ridgwayi with incomta/eremonoma.

I am not aware of any formal analysis comparing incomta/eremonoma vs. murina/wagae/ignobilis, but

the differences are striking based on my recordings and field experience with

both in Argentina/Bolivia and Venezuela, backed up also by recordings by others

(notably by P. Schwartz in Venezuela). The calls, diurnal song and dawn songs

are clearly different, even when they share an overall "Phaeomyias"

feel/structure to them.

4) Further splits in P.

murina/wagae/ignobilis: This clade is possibly the most problematic

because there is a relatively deep split that may indicate the existence of two

species. The type of P. murina

is lost (type locality Brazil), and wagae

is from E Peru (type locality Chirimoto), and ssp. ignobilis (type locality Villa Montes, Bolivia)

was lumped with murina

by Fitzpatrick (2004). Therefore, without more work comparing type specimens

and matching those to the clades in Zucker et al. (2016), it is not clear which

name should be applicable to which population, and it looks like a decision should

be made regarding a restricted type locality and possibly a neotype designation

for murina (which

apparently have not been done). I also want to note that at least the southern

populations traditionally ascribed to nominate murina and ignobilis

are highly migratory, and that it is likely that several of the more northern

examples from the Peruvian Amazon (green spots) in the tree of Zucker et al.

(2016) are southern migrants. The problem with “who is who” gets diluted (at

the species level) if one decides not to split these two clades, which is

probably the best course at present given the lack of detailed studies

analyzing their vocalizations, the borderline genetic differences and the mess

with which names to apply.

5)

Phaeomyias vs. Nesotriccus: A final note has to do with the

generic names. Nesotriccus Townsend

1895 has priority over Phaeomyias

Berlepsch 1902 (type species Elainea

incomta). Given the position of Nesotriccus

and the levels of divergence, it seems that all the taxa should be placed in Nesotriccus, which is rather

unfortunate from the standpoint of stability. It seems an inescapable change.

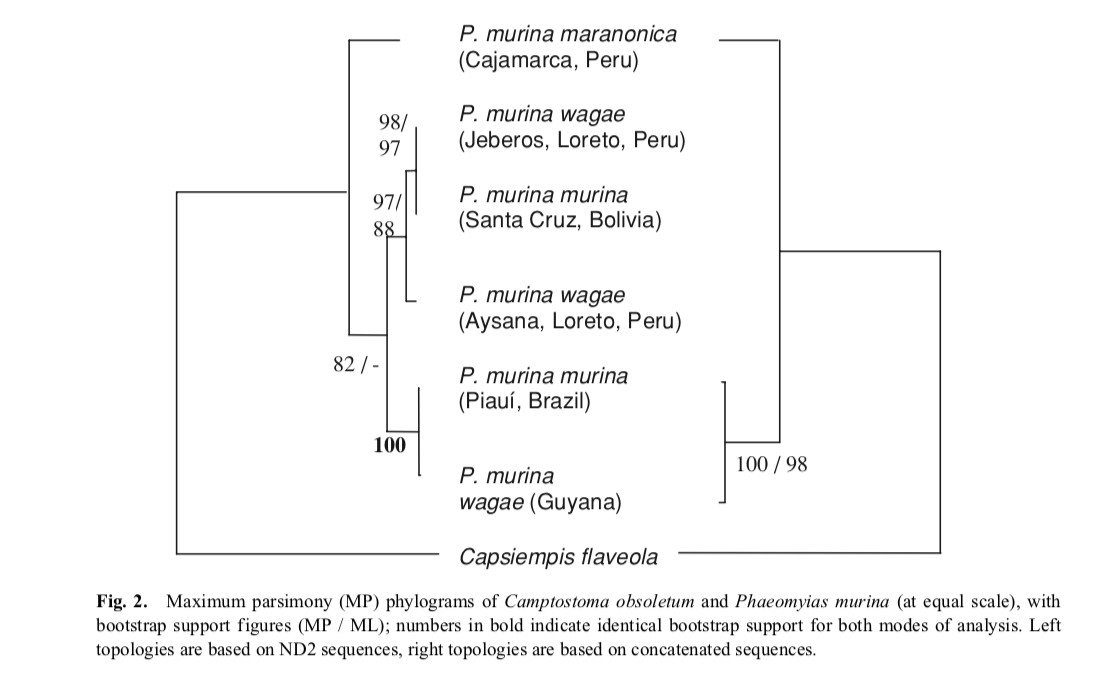

Rheindt

et al. (2008):

Zucker

et al. (2016):

Harvey

et al. (2020):

Note on gender of names: Nesotriccus being masculine (Dickinson & Christidis 2014),

variable epithets need to be corrected, which impacts almost every species and

subspecies names in this group. Only the subspecies wagae is invariable (Dickinson & Christidis 2014). Therefore,

the corrected names would be:

Nesotriccus murinus

Nesotriccus murinus murinus

Nesotriccus murinus wagae

Nesotriccus incomtus

Nesotriccus incomtus incomtus

Nesotriccus incomtus eremonomus

Nesotriccus maranonicus

Nesotriccus tumbezanus

Nesotriccus tumbezanus tumbezanus

Nesotriccus tumbezanus inflavus

Discussion:

I recommend

YES to splits 1, 2 and 3

(i.e., recognize P.

tumbezana, P.

maranonica, and P.

incomta) and YES to keep P.

murina/wagae/ignobilis as a single species until further work

clarifies what is going on there.

The Guyana samples falling in the murina clade or that in the incomta clade might be seen

as problematic by some. However, the ones in the murina clade could pertain to southern migrants

(I am not sure what these specimens look like, and I cannot access the

supplementary material to see whether the collection date makes sense for a

migrant). Regardless of this, Guyana is not the type locality of any of these

birds, and having two nearby samples falling in different clades can also be

interpreted as evidence of two species (much as in tumbezana and maranonica). Also, keeping incomta and murina/wagae/nobilis clades

as one unit creates a somewhat odd paraphyletic species with two distinct vocal

types (i.e., vocalizations of incomta

and the murina/wagae/nobilis

clade differ noticeably, even when no formal analyses exist). I therefore think

that the split 3 is quite straightforward, but what I think is not safe to do

is to perform any more splits in the murina/wagae/nobilis

group; therefore, I recommend a NO on 4.

Also, I recommend a YES on including all species in Nesotriccus.

English names: To be determined in a subsequent proposal

depending on which parts of this one pass.

References:

Angulo, F., Flanagan, J.N.M., Vellinga,

W.-P., Durand, N., 2012. Notes on the birds of Laquipampa Wildlife Refuge,

Lambayeque. Peru. Bull. Br. Ornithol. Club 132, 162–174.

HARVEY, M. G., G. A. BRAVO, S. CLARAMUNT, A. M CUERVO, G. E. DERRYBERRY,

J. BATTILANA, G. F. SEEHOLZER, J. S. MCKAY, B. C. O’MEARA, B. G. FAIRCLOTH, S.

V. EDWARDS, J. PÉREZ-EMÁN, R. G. MOYLE, F. H. SHEDLON, A. ALEIXO, B. T. SMITH,

R. T. CHESSER, L. F. SILVEIRA, J. CRACRAFT, R. T. BRUMFIELD, AND E. P.

DERRYBERRY. The evolution of a tropical

biodiversity hotspot. Science 370:

1343-1348.

Kroodsma, D. E., V. A. Ingallis, T. W.

Sherry, and T. K. Werner. 1987. Songs of

the Cocos Flycatcher: vocal behavior of a suboscine on an isolated oceanic

island.. Condor 89: 75-84

Lanyon, W.E., 1984. The systematic

position of the Cocos Flycatcher. Condor 86, 42–47.

Rheindt, F.E., Norman, J.A., Christidis,

L., 2008. Genetic differentiation across the Andes in two pan-Neotropical

tyrant-flycatcher species. Emu 108, 261–268.

SCHULENBERG, T. S., D. F. STOTZ, D. F. LANE, J. P. O'NEILL, AND T. A.

PARKER III. 2007. Birds of Peru.

Princeton University Press, Princeton, New Jersey, 656 pp.

Schmitt, C.J., Schmitt, D.C., Tiravanti,

J.C., Angulo, F.P., Franke, I., Vallejos, L.M., Pollack, L., Witt, C.C., 2013.

Avifauna of a relict Podocarpus forest in the Cachil Valley, north-west Peru.

Cotinga 35, 17–25.

Sherry, T. W. 1986. Nest, eggs, and reproductive behavior of the

Cocos Flycatcher. Condor 88: 531-532

ZUCKER, M. R., M. G. HARVEY, J. A. OSWALD, A. M. CUERVO,

E. DERRYBERRY, AND R. T. BRUMFIELD.

2016. The Mouse-colored

Tyrannulet (Phaeomyias murina) is a

species complex that includes the Cocos Flycatcher (Nesotriccus ridgwayi), an island form that underwent a population

bottleneck. Molecular Phylogenetics and

Evolution 101: 294–302.

J. I. Areta, February

2023

Comments from Lane: “Well

drat. This proposal basically has rendered a paper I am working on as largely

moot, which is irritating ... not least of which because Tom asked me for

information on this case, and I relayed to him but that I was writing about it

currently. I agree that the species split is clearly necessary, as is the

reason for synonymizing Phaeomyias under Nesotriccus; so, YES to parts 1-3 and 5, and NO to part 4 (recognizing splits within murina/wagae/ignobilis).

Zimmer made a few unusual mistakes when reviewing these taxa, which has

resulted in compounded taxonomic and distributional mistakes through all

subsequent works, and I hope that that topic will remain relevant enough to

warrant me finishing and publishing my work.”

Comments

from Claramunt:

“YES to treat Phaeomyias species under the

genus Nesotriccus, unfortunate but unavoidable. Reluctant YES to 1, 2,

and 3 because the information is not all out and analyzed in a peer reviewed

paper. NO to part 4. Dan: we still want to see your paper.”

Comments

from Stiles:

“A,B-both YES to splits of tumbezana and maranonicus given

genetic differences and probable parapatry, maintaining ridgwayi as

separate; C-YES to separate incomta and eremonoma on genetic

distinctions; D-NO to further splits without further genetic and vocal data; and E-YES to Nesotriccus

for all, its priority is undeniable.”

Comments

from Shaun Peters:

“Normally I

would not get involved in the SACC proposal process, but since I am preparing

some comments to send to both Clements-eBird and IOC regarding their split of Phaeomyias

murina and some other taxonomic decisions (presumably based on a what is

coming from WGAC), I thought I'd share my thoughts with you, which you will

find in the attached pdf* (converted from original word file to reduce file

size). Also attached are the maps from the pdf and Supplementary Table 1 from

Harvey et al listing specimen localities.

“To summarize:

“The proposed

split of

P. murina in to 4 species is essentially based on

genetic data and, in particular, paraphyly. This mainly comes from Zucker et al. (2016), but they only used a single mitochondrial gene (ND2). Harvey et al. (2020), which used UCEs, has limited sampling (6 samples,

no samples from P. m. murina). The trees in these two papers are

broadly similar with the tumbezana and murina groups forming separate clades and Nesotriccus ridgwayi as sister to the incomta group, but not with true paraphyly, but what I call

'pseudo-paraphyly' - this being the case in Harvey et al and also in Zucker et al once the tumbezana clade

is separated off as a separate species. 'Pseudo-paraphyly' does not require a

mandatory split under a BSC.

“Zucker et al. then proposed a split of maranonica (which now includes Andean tumbezana) from lowland tumbezana/inflava, mainly

based on their deep genetic divergence, but also citing differences in

morphology and vocalizations. There do appear to be differences between coastal tumbezana and maranonica, but there are few

available recordings of Andean tumbezana and inflava (the latter being the most distinct taxon in

morphology), and there may well be vocal differences between inflava and lowland tumbezana.

“Harvey et al. then split incomta from murina based on paraphyly but, as previously stated, this is

actually a case of 'pseudo-paraphyly' so is not necessary under BSC. Nacho

mentions differences in vocalizations, but the situation is a little more

complicated than he stated. Listening to vocalizations over the whole range of

the murina group, eastern and southern birds (murina)

generally have rather burry dawn songs and calls with northern birds (incomta)

having clear dawn songs and calls, although some daytime songs from incomta have a burry quality. Interestingly, recordings of wagae resemble incomta in their pure tone, whilst those of ignobilis seem closer to murina than wagae. Thus there may well be three (or four) vocal types within

the murina group. There is also the fact that incomta and murina are

very similar in morphology and it is wagae that

stands apart (see Zimmer, 1941, although based on Dan's comments on the

proposal this may not be the case??).

“Thus, there may

well be more than one species involved within the murina group, but it requires more widespread genetic analysis

(of both nuclear and mitochondrial genes) as well as a detailed comparison of

vocalizations across the whole range of the murina group.”

[* distributed to SACC

members separately]

Comments

from Shaun Peters (now voting for Pacheco): “Since a

split of a broad tumbezana (including maranonica) is not on the table I would have to vote 'No' on Parts 1

and 2. Although lowland tumbezana and maranonica clearly differ vocally, I'm not certain about the vocal

affinities of Andean tumbezana and inflava (more work is needed here). 'No' votes on parts 3 and 4 are

more straightforward for me - more work (how the genetic, morphological and

vocal data marry up) needs doing here, Thus, here are my votes

“Part 1 - NO

Part 2 - NO

Part 3 - NO

Part 4 - NO

Part 5 – YES”

Additional

comments from Areta:

“Shaun, thanks for the diligent analysis shared. I should

have checked for the restricted type locality for murinus; however; even if there might be more splits in the murina-wagae-ignobilis, data are far from satisfactory and nomenclatural problems

should be cleared before proceeding on this front. For example, although murina has been

restricted to a type locality, apparently no neotype has been designated; thus,

flimsy ground upon which to decide.

“Also, bear in mind that the support for the Guyana and Colombia

samples in the Harvey et al tree is so low as to render this a complete

uncertainty, and cannot be interpreted as introgression with any confidence.

So, there is no "pseudo-paraphyly" here.

“After reading Shaun’s comments (and incorporating the caveat that

the Harvey et al. tree cannot be used to discard or confirm paraphyly in the murina

group), the genetic and vocal data are consistent with the treatment that I

advocate: split incomta/eremonoma, split tumbezana, split maranonica,

and leave murinus as one species until the proper studies needed to sort

out their taxonomy are published (it is possible to split the NE and SW clades

as separate species, but I didn´t want to go that far in the proposal, given

the confusion surrounding the distribution of the different taxa, the lack of a

proper vocal analysis, and type-specimen issues). As I mentioned in the

proposal, the likely coexistence of taxa from two different clades in Guyana

provides further support to split incomta/eremonoma from the murinus

group. Now, whether these breed there or not, I don´t know. Maybe Dan has

researched this more in-depth for his paper.

“I think that there are plenty of questions here to be answered,

but I think that the SACC proposal is consistent with the minimum number of

necessary splits that are well-supported by the data."

Comments

from Bonaccorso:

“YES to part 5. The evidence from the broad sampling

of Zucker et al. (2016) on ND2 and the restricted UCEs sample from Harvey et

al. (2020) are consistent with Nesotriccus well nested within

Phaeomyias. If Nesotriccus is an older name, the change of all Phaeomyias of Nesotriccus is adequate.

“NO to the splits (parts 1, 2, 3, 4). The splitting of these taxa

would be based solely on Zucker et al. (2016) ND2 data and their presumable

paraphyly. Such a split would need a more integrative approach with more

genetic data, including potential contact zones and some diagnostic characters,

either morphological or vocal.”

Comments from Robbins: “The combination of genetic and

vocal data do support the minimum splits that Nacho has proposed, thus I vote

for acceptance of 1,2,3, and of course, # 5, using Nesotriccus for all

these taxa.

“With regard to whether birds breed in Guyana, samples that we

collected during March in the Rupununi do breed there (see Appendix 1 in

Robbins et al. (2004. Avifauna of the Guyana Southern Rupununi, with

comparisons to other savannas of northern South America. Ornitologia

Neotropical 15:173-200). For example, I

recorded persistently singing birds (ML 145030, 145010) on the same day/site

that birds were collected that had enlarged testes, e.g., 7 x 4 mm (KU 90771). With regard to the two LSU Guyana samples in

Zucker et al. (2016), thanks to Steve Cardiff, a photo is attached below of

those specimens (collected by Santiago). Note how strikingly different those

two specimens are, even though both are adult females with similar gonadal

data, taken at the same locality within two days of each other (during the

austral winter). So, I suspect one is a

migrant and the other a resident. The

paler bird is more consistent with material that we have collected throughout

the year in Guyana.”

“To add a bit of perspective, three specimens (KU 90771, 90884-5)

taken in the southern Rupununi during late March to mid-April are

indistinguishable from a specimen with enlarged testes (6 x 3 mm) taken on 31

October (KU 96872) from Jujuy, Argentina! Furthermore, in Birds of the World, which has

already split the murina complex into multiple species, states the two

subspecies of the Northern Mouse-colored Tyrannulet (Nesotriccus incomta)

differ in that Central American N. i. eremonoma is distinguished from

nominate by having the wing coverts edged dull buff. The aforementioned March-April birds from

Guyana have the wing coverts edged dull buff.

“So, I would submit that delineation of subspecies using plumage

would seem highly problematic: voice and genetic data should define taxa in

this complex.

“Clearly, more in-depth study

is needed, but I think it is a major step forward in recognizing the proposed

splits in this proposal.”

Comments

from Zimmer:

“This is definitely a messy taxonomic and nomenclatural case, and one for which

we don’t have enough data to completely untangle. However, I think there is enough evidence for

us to move things forward on some fronts, so, here goes: YES to splits 1, 2 & 3, in

spite of some unresolved issues regarding vocal variation within tumbezana

(coastal versus Andean) and how that relates to both inflava and maranonica. I think it is a step forward to make these

splits to at least begin to address some of the vocal and genetic

variation. But, like Nacho, I don’t

think we know enough about what’s going on to justify any further splitting at

this time, within the murina/wagae/nobilis group, so NO on 4. Also, a clear YES on 5, since Nesotriccus

is clearly embedded within Phaeomyias, and the priority of Nesotriccus

is undisputed.

Additional

comments from Lane:

“Thanks to some queries from Niels Krabbe on voices

of some Ecuadorian populations of this complex, I have reviewed recordings in

both Xeno-canto and Macaulay Library and found that it seems that both have

made a real hash of the application of taxonomic names to populations. Macaulay

has already instituted the split of N. incomtus from N. murinus, but many

of the recordings placed in the former sound more to me like wagae, which is placed in the latter, and which is the

cis-Andean form I know best. As Nacho lays out, the type locality of incomtus is Cartagena,

and there are not a lot of recordings from around there for me to feel like I

really have a grasp of what that taxon sounds like (I can't find any real dawn

song from around Cartagena, for example). My gut feeling is that the name incomtus is best

applied to birds from northern Colombian lowlands east along the Venezuelan

coast (possibly in the northernmost edge of the Llanos as well?), and,

presumably, into Guyana (as per the Zucker et al. phylogeny), but I don't hear

recordings from Guyana that sound like those from Colombia. To my ear, many of

the dawn songs available in ML from Venezuela and Guyana sound very much like

the waga

song I know from Peru (see here for a near

topotypical example: https://macaulaylibrary.org/asset/234404). Indeed,

nearly all the highland birds on XC from central Colombia and Ecuador seem to

sound much more like wagae, but with

higher-pitched voices. This suggests that the

incomtus group is

far more range-restricted than it seems to have been thought (at least based on

the maps available on XC and eBird/Birds of the World... which may or may not

be of any value in this discussion anyway), but more importantly, unless each

listener is carefully combing the recordings for topotypical examples and

working outward from there, they will be completely swamped by misinformation

as to the voice characters of each group. I hear much variation within all

these murinus/incomtus

populations, including what appears to be several unrecognized

taxa (the highland birds from Colombia and Ecuador, and then birds from NE

Brazil seem fairly distinctive compared to other cis-Andean populations. That

last tidbit calls into the light the proper application of the name

murinus: is it from NE Brazil or SE? According to Peters, Pinto

restricted the name to Bahia, so presumably that means this unique voice type

from NE Brazil is true murinus

(assuming Pinto did his homework!), leaving the more widespread

form, including the migratory populations Nacho talks about, as

ignobilis (which was

unhelpfully synonymized by HBW, clearly a move that must be reversed!), which

sounds more like wagae, but still

seems distinctive to my ear.

“The long and short of it is: this

complex is a mess, and I think this all needs to be ironed out before we go

splitting the murinus/incomtus

complex, even if it remains paraphyletic with respect to

N. ridgwayi... In some ways, this study mirrors that of

Nyctiprogne in having a

phylogeny that needs some "ground-truthing" to make sense of the

patterns it draws. So, with all that, I am changing my vote for Part 3 to NO.

We need so much more information to make that call!”

Additional comments from Robbins: “Yes, indeed this is a

mess that needs to be sorted out. Given what Dan has underscored, I’ll change

my 956.3 vote of splitting incomtus to a NO until things get clarified.”

Comments from Niels Krabbe (voting for Remsen); “As

pointed out by Dan, Mouse-colored Tyrannulet encompasses a larger number of

populations of different vocal types than the literature would suggest, and for

many of these there is still too little material available to properly define

them.

“After listening to recordings, I must agree that the call and

dawn song of maranonicus are strikingly different from those of tumbezana

occurring on the same slope, but it is unsatisfactory that this suggested split

is based partly on Lane's and Angulo's personal comments. So as a reminder that

SACC proposals should be based on published material, I cannot vote for this

split at present. That Nesotriccus has priority for the entire complex

is, as shown by both Zucker et al. (2016) and Harvey et al. (2020), indeed,

unquestionable.

“So my vote goes:

“Options 1-4: NO

“Option 5: YES apply the generic name Nesotriccus for the entire

complex.”

Comments from Glenn Seeholzer (voting for Jaramillo): “In

general I feel that the perfectly sampled, integrated taxonomic treatise should

not be the standard for every proposal. Very few have the resources or time to

indulge in such work meaning that obviously necessary and justified changes

will be stalled for lack of a peer-reviewed paper stating what was obvious at

the start. On the other hand, the split in Part 3 (already instituted by the

Clements/eBird taxonomy) feels hasty given what Dan and Shaun have uncovered so

this definitely feels like a case where more in-depth vocal analysis is

necessary.

“YES to Parts 1 and 2 - This split would be based primarily on the

assumption of close parapatry between the aligned clusters of vocal, plumage,

and genetic traits represented by tumbezana/inflava and maranonica.

A quick review of recordings on Xeno-canto and ML shows that the distinctive maranonica

vocal group is clearly present in the upper elevations of the west slope in

Piura (see Dan's great documentation here at 1900m) and published evidence that tumbezana

occurs to at least these elevations nearby (Angulo et al. 2011). While it would

be nice to have this better documented, I think the burden of proof is on those

who would say that these groups are not distinct enough, are not actually in

contact, or are somehow hybridizing and should be lumped.

“NO to Parts 3 and 4 - This

would create a paraphyletic incomta/murina with respect to ridgwayi,

which I'm fine with because paraphyly is compatible with the BSC. Ridgwayi

is clearly a diagnosable unit, but it is unclear what the taxonomic units are

among the constituent incomta + murina taxa. While the geographic

extremes of incomta/eremonoma vs. murina/wagae/ignobilis

may be quite different at their extremes, as Nacho states in the proposal,

Shaun and Dan seem to have uncovered more complex patterns of vocal variation

with potential evidence of intermediates (wagae) and multiple distinct

vocal groups in each putative species. For the same reasons that it seems

premature to split murina/wagae/ignobilis with so little

documentation (Part 4), it seems premature and potentially incorrect to split incomta/eremonoma

and murina/wagae/ignobilis (Part 3). I feel a detailed

published analysis of vocal variation is warranted in this case to define the

diagnostic vocal traits of the units and their geographic distributions before

considering further splitting.

“YES to part 5 - Nesotriccus has priority over Phaeomyias,

so ciao Phaeomyias and long runs of vowels.”