Proposal (959) to South

American Classification Committee

Recognize Pogonotriccus

as separate from Phylloscartes

The

current SACC note reads:

"31. The species poecilotis, ophthalmicus,

orbitalis, venezuelanus, eximius, gualaquizae, and flaviventris

were formerly (e.g., Pinto 1944, Meyer de Schauensee 1970) placed in the genus Pogonotriccus,

but this was merged into Phylloscartes by Traylor (1977<?>,

1979a). The species poecilotis through eximius do form a

distinctive group within the genus and thus the English name Bristle-Tyrant is

retained for them, following Ridgely & Tudor (1994). Hilty & Brown

(1986), Ridgely & Greenfield (2001), Hilty (2003), and Fitzpatrick (2004)

retained Pogonotriccus because this group has consistent morphological

and behavioral differences from Phylloscartes. See also Graves (1988)

and Fitzpatrick & Stotz (1997) for support for retention of Pogonotriccus.

Dickinson & Christidis (2014) also resurrected Pogonotriccus. SACC proposal badly needed."

First,

I want to say that the extremely broad concept of Phylloscartes adopted

by Traylor (1977) has been shown to be untenable on several fronts.

Phylogenetic

data in the mega-paper of Harvey et al. (2020) indicates that the current

delineation of Pogonotriccus with 7 species is inadequate. For both

genera to be monophyletic, the genus Pogonotriccus would need to also

include P. difficilis and P. paulista (i.e., include 9 species),

removing these from Phylloscartes,

and will also need to exclude P. flaviventris. The split between

the monophyletic (9 species) Pogonotriccus and Phylloscartes is

around 10 my (well within the splits of several genera in the Tyrannidae).

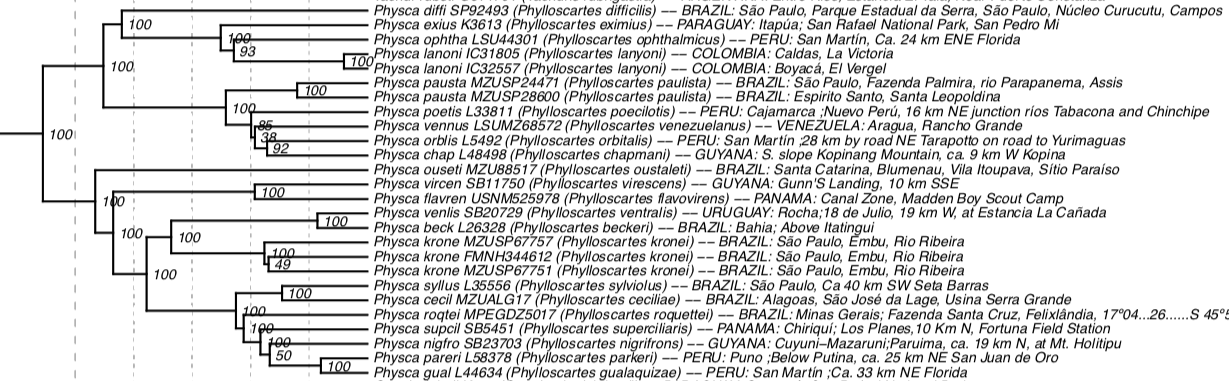

Harvey

et al. (2020) tree:

So,

we have two options here:

1.

Broad

Phylloscartes (which has priority, see below): would include all the

species shown

2.

Two

genera (Pogonotriccus with 9 species, including P. difficilis and

P. paulista, and Phylloscartes)

These

would be the species to be placed in Pogonotriccus

(see that some would be "tyrannulets" and some would be

"bristle-tyrants"; an inconsistency that may need or may not need

discussion):

|

Marble-faced

Bristle-Tyrant |

Pogonotriccus

ophthalmicus |

|

Venezuelan

Bristle-Tyrant |

Pogonotriccus

venezuelanus |

|

Antioquia

Bristle-Tyrant |

Pogonotriccus lanyoni |

|

Spectacled

Bristle-Tyrant |

Pogonotriccus

orbitalis |

|

Variegated

Bristle-Tyrant |

Pogonotriccus

poecilotis |

|

Southern

Bristle-Tyrant |

Pogonotriccus eximius |

|

Chapman's

Bristle-Tyrant |

Pogonotriccus

chapmani |

|

São

Paulo Tyrannulet |

Pogonotriccus

paulista |

|

Serra

do Mar Tyrannulet |

Pogonotriccus

difficilis |

|

|

|

Phylloscartes publication date:

see here

Pogonotriccus

publication date: see here

A

YES on this proposal endorse the two-genus treatment, with paulista and difficilis

moved to Pogonotriccus. In addition to the deep split, other features

that seem well-marked in most Pogonotriccus and lacking or much reduced

in Phylloscartes are a well-marked, broad crescent below the eye,

upright posture and relatively short tail (in comparison to more horizontal

posture and longer tail in Phylloscartes), and the habit of frequently

flicking one wing (several Leptopogon also do this regularly, but it

seems to be rare in Phylloscartes). I have personal experience with Pogonotriccus eximius, ophthalmicus, venezuelanus, poecilotis,

paulista and chapmani, and with Phylloscartes

ventralis, kronei, oustaleti, sylviolus and nigrifrons.

The behavioral distinctions hold true for all these species.

References:

HARVEY, M. G., G. A. BRAVO, S. CLARAMUNT, A. M CUERVO, G. E. DERRYBERRY,

J. BATTILANA, G. F. SEEHOLZER, J. S. MCKAY, B. C. O’MEARA, B. G. FAIRCLOTH, S.

V. EDWARDS, J. PÉREZ-EMÁN, R. G. MOYLE, F. H. SHEDLON, A. ALEIXO, B. T. SMITH,

R. T. CHESSER, L. F. SILVEIRA, J. CRACRAFT, R. T. BRUMFIELD, AND E. P.

DERRYBERRY. The evolution of a tropical

biodiversity hotspot. Science 370:

1343-1348.

Nacho Areta, February

2023

Note from Remsen: Nacho noted the

problem of paulista and difficilis having the English names

“Tyrannulet”, and so if option 2 is favored, then would anyone be opposed to

changing their last names to “Bristle-Tyrant”?

Do we need a separate proposal on this?

Seems like such a no-brainer to me that an official proposal seems

superfluous and unnecessary.”

Comments

from Areta:

“YES. A large Phylloscartes is

phylogenetically quite uninformative, and Pogonotriccus

has a suite of supporting phenotypic features and a deep genetic divergence

that to me suggest genus-level differentiation.

Comments

from Remsen:

“YES. The merger of Pogonotriccus into Phylloscartes was widely regarded

as unwise by field people at the time, and in fact most subsequent authors

continued to maintain Pogonotriccus as a separate

genus. Now we have solid genetic data to

support its resurrection. The division

is estimated at more than 5 MYA, which is consistent with my informal criterion

for recognizing separate genera. It looks like phenotypic evidence is also

consistent with the split.”

“As you can tell from my appended comment on English names,

I favor implementing this without a separate proposal. We have a chance to have a 1-to-1 match

between genus and English name, with the bonus that two fewer tyrannids are

left with the non-informative name “Tyrannulet.”

Comments from Zimmer: “YES.

This one has always seemed like a slam-dunk to me based upon the behavioral and

morphological distinctions mentioned by Nacho in the Proposal, and now, the

phylogenetic data from Harvey et al. (2020) makes it clear, what field people

maintained all along. The 2 species that

would need to be moved from Phylloscartes to

Pogonotriccus in order for each group to be monophyletic,

P. difficilis and P. paulista, are birds

I know well from Brazil’s Atlantic Forest, and in behavior, plumage, and overall

morphology, both fit comfortably within

Pogonotriccus, and are outliers for “true”

Phylloscartes.

“As for Van’s note on English names: I don’t think we need a

separate proposal to deal with this. Count me as a

YES for making difficilis and

paulista “Bristle-Tyrants” and leaving the true

Phylloscartes as “Tyrannulets”. A similar change of English

name was made for P. chapmani

some time back, and we should definitely try to keep that 1-to-1

match between Genus name and English group name intact.”

Comments from Lane: “YES to recognizing Pogonotriccus separate from Phylloscartes.

And, I agree with Kevin that we don't have to have a separate proposal to add

"Bristle-Tyrant" to all species now included in Pogonotriccus.

It simply makes sense.”

Comments from Stiles: “YES to split this genus

from Phyllomyias, based on genetics and vocalizations: also I see no

problem in using the E-name of “Bristle-Tyrant” for paulista and difficilis

(the degree of “bristliness” is quite variable in the “true” Pogonotriccus

in any case.”

Comments

from Stotz (voting for Pacheco): “I vote YES on the

split of Pogonotriccus and Phylloscartes and the moving of difficilis

and paulista from their traditional placement in Phylloscartes

(pre-lump of Pogonotriccus and Phylloscartes) into Pogonotriccus,

where the genetic evidence clearly show them to be imbedded. I further favor

using Bristle-Tyrant for both difficilis and paulista in recognition of

this now treatment. This will make Bristle-Tyrants and Pogonotriccus

congruent, and is doubtful to cause any confusion. Traylor in my view did

a good job in making sense of the relationships of among various Tyrannid

species and groups, but over-lumped at the generic level (besides this, also

seen in the Tody-Tyrants and Tody-Flycatchers). Almost from the moment Pogonotriccus

and Phylloscartes were lumped, people with experience with these species

in the field noted the behavioral differences and some morphological

differences between the species previously in Pogonotriccus and those

originally in Phylloscartes. Now

that we have genetic data supporting this split, I think it is a good idea to

re-split the Bristle-Tyrants back into Pogonotriccus. I think it is worth noting that gualaquizae

was a Pogonotriccus pre-Traylor, but moves in the opposite direction

from difficilis and paulista, and clearly belongs in Phylloscartes.”

Additional

comments from Zimmer:

“It seems to me that we have, as a committee,

grappled with exactly these same sorts of scenarios several times, with the

publication of relatively complete (= broadly taxon-sampled) phylogenies for

various groups. For example, think of recent generic realignments of “tanagers”,

antbirds, and Buteonine raptors, in which we have been confronted with either

splitting previously broadly defined genera into multiple genera, or, lumping

one or more current genera into a single, more inclusive genus in order to

achieve monophyletic genera. Either path to monophyly can be defended on purely

genetic grounds, and thus, it comes down to a matter of taste, or preference,

in how each of us views a genus. Personally, I tend to prefer to recognize

distinctive, morphologically or behaviorally homogeneous groups of related

species at the generic level when possible, because I find such arrangements

more informative than broadly defined, heterogeneous groups. However, the

genetic data from broadly sampled, diverse assemblages, often reveal novel

relationships that defy patterns of morphological, vocal or behavioral

characters that would otherwise allow us to diagnose distinct subgroups.

The question then becomes one of whether we ignore the broader pattern

because it isn’t universal to every member of the clade, and maintain

everything in one broadly defined, heterogeneous group, or,

do we rely on the genetic data to define the more narrowly monophyletic

subgrouping, and recognize that the subgroups, are, on the whole, still largely

diagnosable, even if there are individual taxa that are outliers.

“To my thinking, this still comes down to taste/preference, with

no single, ideologically right/wrong answer.

“For starters, let’s set aside the 2 species (difficilis, paulista)

that would need to “move” in order for Pogonotriccus and Phylloscartes

to be monophyletic if recognized, as is unambiguously the case, based on the

genetic data of Harvey et al (2020). The first order of business then, is

whether the proposed groups are, indeed, distinct, or meaningful units.

“In the Proposal, Nacho clearly states that he has personal

experience with 6 of the proposed Pogonotriccus species (5 if you exclude paulista), and 5 of the “true” Phylloscartes. For my part, I have field experience with 22

of the 23 currently recognized species of Phylloscartes/Pogonotriccus (including extralimital flavovirens) – lacking experience

only with P. lanyoni – and would characterize my familiarity

with all but Chapman’s, Parker’s and Ecuadorian tyrannulets, and Spectacled

Bristle-Tyrant as being extensive.

“It has been pointed out that Pogonotriccus, as

traditionally defined, was found to be polyphyletic, meaning that some species

(e.g. flaviventris) that would be treated as belonging to Phylloscartes

if this proposal passes, actually more closely resemble the newly defined Pogonotriccus.

But that is because the “traditionally

defined” Pogonotriccus was defined solely by morphological characters,

the inconsistency of which was also why Traylor advocated for subsuming Pogonotriccus

into Phylloscartes in the first place!

“If morphology was all we had to go on, then I’d probably be right

there with Traylor in advising against recognizing Pogonotriccus. Fortunately, we have more than just morphology

to go on. Field ornithologists who knew

the birds in the field, have been advocating for the distinctiveness of the Pogonotriccus

subgroup versus “true” Phylloscartes for decades (think Hilty,

Fitzpatrick, Ridgely, etc.), and essentially from the moment Pogonotriccus

was subsumed into a broad Phylloscartes! One only has to look at Van’s Note on our

website, which Nacho included in the Proposal, to see the depth of support in

the literature for retaining/resurrecting Pogonotriccus. Note also, that the polyphyly of traditionally

defined Pogonotriccus was already predicted long before it was confirmed

by the recent work of Harvey et al (2020), precisely due to differences in

posture, behavior, and ecology noted by field workers. These differences led

Hilty (2003, Birds of Venezuela) and others, to not only retain Pogonotriccus,

but to treat flaviventris and nigrifrons as Phylloscartes,

and to treat chapmani as a Bristle-Tyrant.

“Basically, in my experience, again, setting aside difficilis

and paulista, all of the “true” Phylloscartes, are canopy- and subcanopy-dwelling

birds, with horizontal postures, that cock their relatively long tails most of

the time (often pronounced), imparting a distinctly gnatcatcher-like impression,

and they forage mostly by hopping from side-to-side outwardly along

branches, and perch-gleaning, or, by making short lunges or sally-strikes. Conversely, all of the “true” Pogonotriccus

(again, setting aside difficilis and paulista) are birds of the

understory to midstory, sticking within shade or cover, perch with a much more

consistently upright posture (usually with tail hanging down, and seldom, if

ever, cocked), and forage mostly by upward-directed sally-strikes or

hover-gleans. Again, in my experience,

which includes 20 of the 21 species (setting aside difficilis and paulista),

these distinctions between the members of the two groups are rock solid,

and 100% consistent.

“The exaggerated one-wing-upward-flick, although eye-catching, is

not unique to Pogonotriccus, and is regularly done by some species of “true”

Phylloscartes. That said, it proves nothing about the relationship of Pogonotriccus

to Phylloscartes, since the same behavior is found in some species of Leptopogon/Mionectes.

“So, that’s my two cents on the distinctiveness of Pogonotriccus

versus Phylloscartes. So, what about difficilis and paulista,

the two species which would need to be moved to Pogonotriccus (as

demonstrated in the phylogeny of Harvey et al, 2020), in order to make both Pogonotriccus

and Phylloscartes monophyletic?

This is what I said in my original comments:

‘The 2 species that would need to

be moved from Phylloscartes to Pogonotriccus in order for each

group to be monophyletic, P.

difficilis and P. paulista,

are birds I know well from Brazil’s Atlantic Forest, and in behavior, plumage,

and overall morphology, both fit comfortably within Pogonotriccus, and are outliers for

“true” Phylloscartes.’

“What I should have said, is that both difficilis and paulista

are what I would call “tweeners” (to use a basketball term) — not fitting

neatly into either of the two well-defined (on posture, behavior, foraging

ecology) groups – but also, in my opinion, still closer to Pogonotriccus

than to Phylloscartes, and therefore, not inconsistent with placement in

Pogonotriccus, which is where the genetic data clearly places them.

“Neither species is as consistently upright in posture as the

other Pogonotriccus, but neither are they as consistently horizontal as

all of the other Phylloscartes (this particularly true of paulista),

and neither of them consistently hold their tails cocked to the extent of

typical Phylloscartes (I have plenty of photos of both species that back

this up.). Neither species hangs out in the canopy and subcanopy (as does

typical Phylloscartes), and both, in my experience, stick within the

shaded understory, often keeping within cover, and often with 1-2 meters or

less of the ground – again, much more like typical Pogonotriccus, and

completely contrary to typical Phylloscartes. I will concede that the posture of difficilis

is closer to that of typical Phylloscartes, but the height at which it

forages, and its general foraging behavior (upward-directed sally-strikes and

hover-gleans) are much closer to Pogonotriccus in my experience. São

Paulo Tyrannulet is an oddball in that it is notably small and over-the-top

hyperactive (“não pode parar” is the Brazilian name), and closely

associated pairs respond to playback by dropping almost to the ground and

engaging in animated duets, as if they had OD’d on Red Bull. That doesn’t

really fit either group, but, again, the genetic data tell us pretty clearly

where their affinities lie. As for vocal

characters, I would note that there’s really no such thing as a yardstick for

generic-level vocal differences, and, again, IMO, the squeaky vocalizations of difficilis

and the duets of paulista, although pretty different from eximius,

are also pretty different from any other species of Phylloscartes that I

can think of off the top of my head.”

“In sum, I think that 21 of the 23 species of currently recognized

Phylloscartes pretty clearly fall into one of two groups based on

posture, foraging ecology. and behavior, and the other two species, although

not a perfect fit for either group, are not inconsistent with placement in Pogonotriccus,

which is where the genetic data clearly places them.”

Additional comments from Remsen: “Reading Kevin’s comments

on posture and foraging behavior … I wonder how many genes are involved in

those differences? One day, maybe we will know, but it

seems likely that this sort of flexible wiring is likely under complex genetic

control, and that the differences likely have influences on the optic, neural,

and myological systems in a bird.”

Comments from Claramunt: “YES. A reluctant one because the phenotypic

diagnosability is not clear. But both clades are considerably species-rich and

old, so, in the big scheme of things, and given that Pogonotriccus has

been used often, I vote for recognizing two different genera for this group.”

Comments

from Robbins:

“YES. Based primarily on Kevin's comments and the

fact that Pogonotriccus has been in use for a long time, I vote yes for

recognizing the genus.”