Proposal (962) to South

American Classification Committee

Species

limits and generic placement of Phyllomyias

burmeisteri and the generic limits

of Tyranniscus

Our

current SACC notes state:

"2. Although Fitzpatrick (2004) followed Traylor's (1977,

1979a) broad definition of Phyllomyias, he

noted that this genus is likely polyphyletic, with P. fasciatus, P.

griseocapilla, and P. griseiceps possibly forming a group unrelated

to the other species, which would force minimally the resurrection of Tyranniscus

(see Note 6).

2a. The species

burmeisteri was formerly (e.g., Cory & Hellmayr 1927, Pinto 1944, Meyer de Schauensee 1970) separated in

the genus Acrochordopus based on tarsal morphology, but Acrochordopus

was merged into Phyllomyias by Traylor (1977, 1979a). Acrochordopus

was considered to belong in the Cotingidae by Ridgway (1907) and Wetmore &

Phelps (1956). The name Idiotriccus was formerly (e.g. Ridgway

1907) used for Acrochordopus.

2b. Wetmore (1972),

Stiles & Skutch (1989), Sibley & Monroe (1990), Ridgely & Tudor

(1994), and Ridgely & Greenfield (2001) recognized the northern subspecies

zeledoni as a separate species from Phyllomyias burmeisteri based on

described vocal differences; this treatment returns to earlier ones (Cory &

Hellmayr 1927, Zimmer 1941c, Phelps & Phelps 1950a) that treated the two as

separate before Meyer de Schauensee's (1966, 1970) and Traylor's

(1977<?>, 1979a) classifications. Stiles & Skutch (1989) further recognized

Andean birds as a separate species, P. leucogonys, from Central American

P. zeledoni, returning to the classification of (REF). Elevation of

these taxa to species rank was not followed by Fitzpatrick (2004) due to lack

of published analyses of vocal differences or other data. SACC proposal needed.

6. The species nigrocapillus,

cinereiceps, and uropygialis were formerly (e.g., Ridgway 1907,

Cory & Hellmayr 1927, Zimmer 1941b, Phelps & Phelps 1950a, Meyer de

Schauensee 1970) placed in a separate genus, Tyranniscus, but they were

transferred to Phyllomyias by Traylor (1977, 1979a). <check gracilipes

-- in Tyranniscus in Pinto 1944>

"

Species

limits:

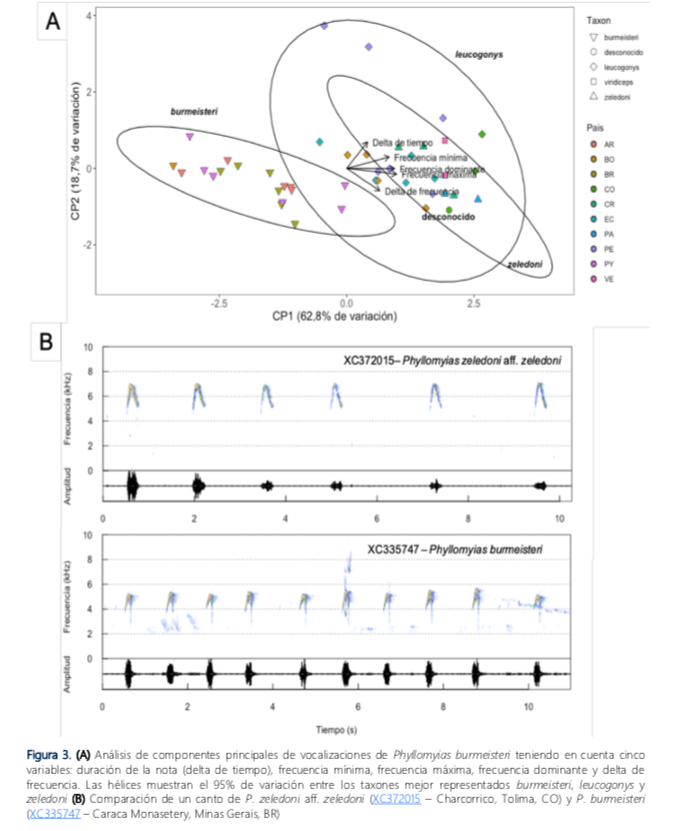

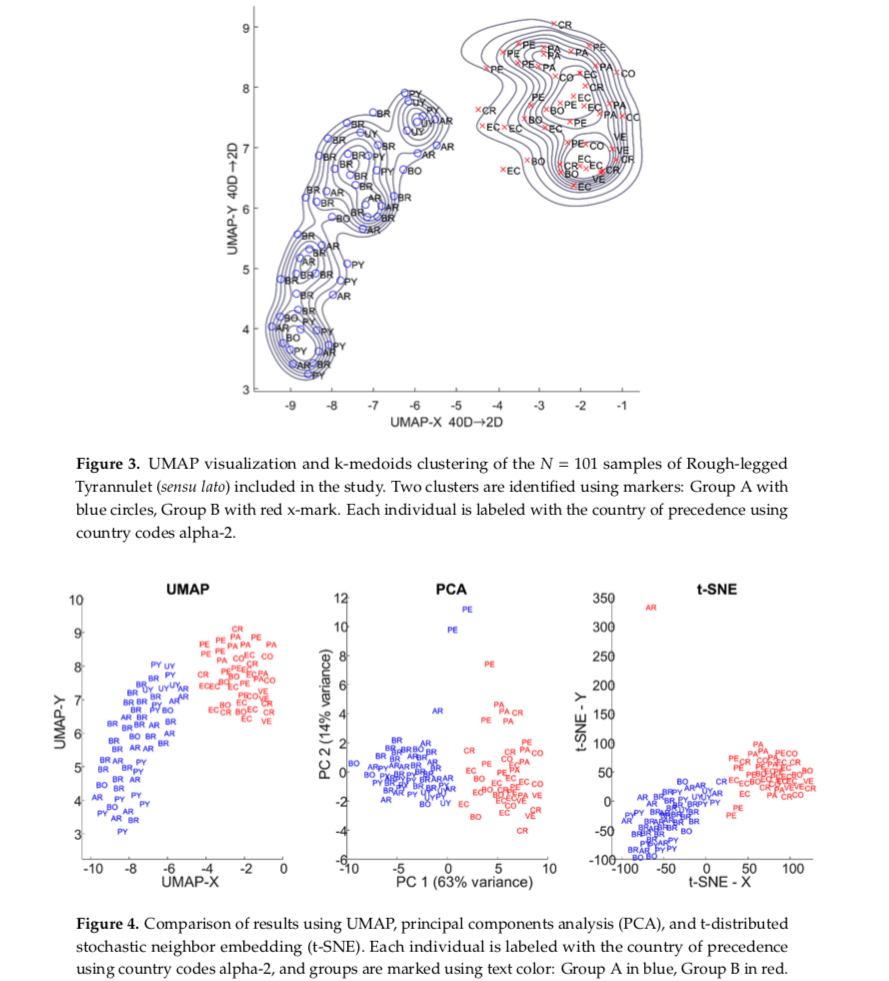

Parra-Hernández et al. (2020a, b) performed acoustic analyses to

understand vocal variation in P.

burmeisteri. Their results support the recognition of two vocal clusters.

Figure 3 in Parra-Hernández

et al. (2020a) shows spectrograms and a PCA.

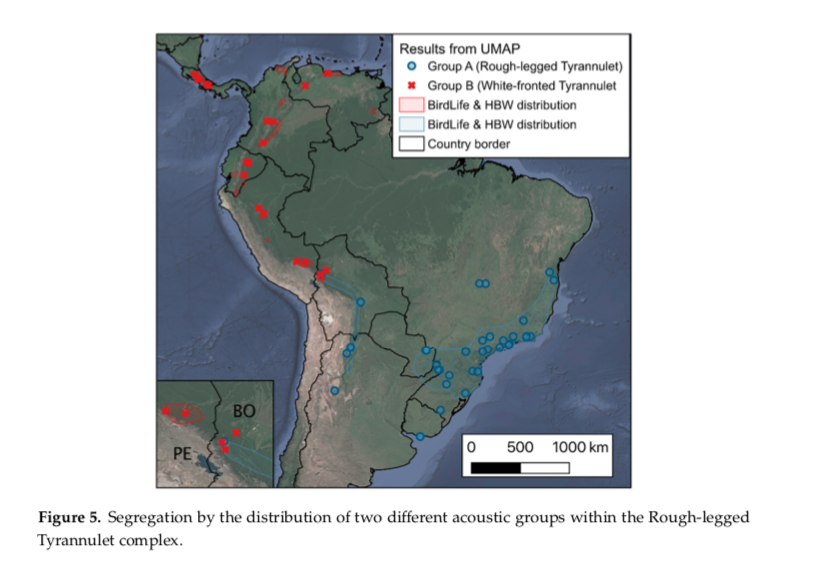

Figures 3-5 in Parra-Hernández et al. (2020b) show

the geographic distribution of data points analyzed, together with different

analyses performed in order to try to group the different vocal types. Note

here that according to these results, leucogonys

would fall within the spectrum of variation of zeledoni.

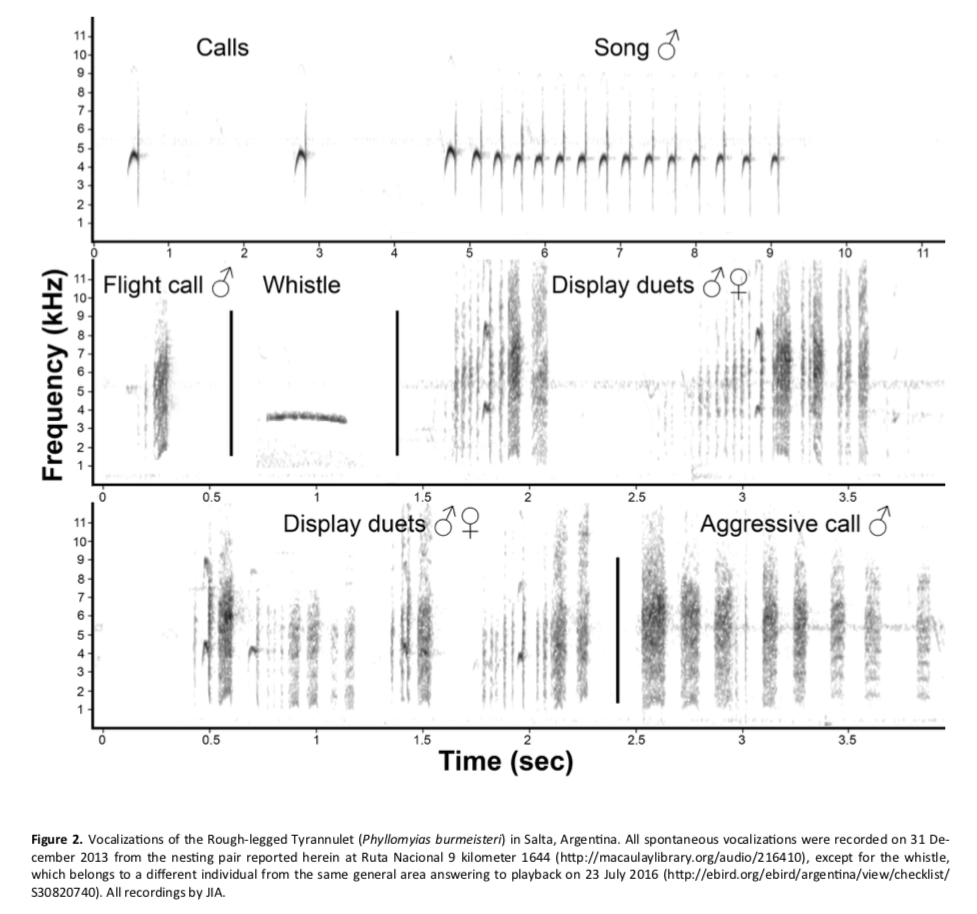

Areta et al (2021) showed some other vocalizations, and

discriminated between calls and song of burmeisteri.

Clearly, there is more to be done in vocal analyses. Notably, burmeisteri has a "two-noted" song repeated in quick succession

(sometimes given at dawn, so perhaps a dawn song...), which might also be

profitably compared to the northern taxa (e.g., this leucogonys recording).

Herzog et al (2016) indicated that in W La

Paz, the taxon present belongs to the zeledoni

group, and they provided separate vocal descriptions for both groups. See for

example here for a song of burmeisteri from Santa Cruz sounding like birds in NW

Argentina and in the Atlantic Forest of Argentina, Brazil and Paraguay, and the

different sounding leucogonys from La Paz. It seems that the two vocal types

are geographically segregated, although the exact turnover point needs further

elucidation. Compare against for example this song of viridiceps the Coastal Cordillera in Venezuela.

There

are three main species-limits options here:

A) One

species treatment: keep all taxa in a wide-ranging P. burmeisteri (this is our current treatment). There is not much

support for this treatment, although one could argue that the vocal

differences, even if diagnostic, are not outstanding. The gap in information in

CN Bolivia could create concern, as if there will be vocally intermediate

individuals, they would come from this area. However, the vocal equivalency

between Atlantic Forest and allopatric Andean birds in the burmeisteri group, may signal that the divergence between leucogonys and burmeisteri is real and could undermine the idea of the existence

of intermediate individuals.

B) Two

species treatment: split P. zeledoni including

wetmorei, viridiceps, bunites,

together with leucogonys from P. burmeisteri. This is the option

supported by vocal analyses in Parra-Hernandez et al. 2020 (a,b).

C) Three

species treatment: split P. zeledoni, P. leucogonys and P. burmeisteri. I would like to hear from those with more

experience with zeledoni and leucogonys on whether they agree with

their treatment as the same species. This would also mean that we need to

decide on which of the South American taxa stay with zeledoni and which are more properly placed with leucogonys.

2) Generic

placement

Regarding the generic placement, Areta et al (2021) discussed

different alternatives following the tree of Harvey et al (2020) and nesting

data:

Phylogenetics

of Phyllomyias and nest structure

The genus Phyllomyias, as currently composed, is clearly

polyphyletic and four groups can be distinguished (Ohlson et al. 2008, Tello et

al. 2009, Harvey et al. 2020). The first group includes the type species of Phyllomyias,

P. fasciatus, which is closely related to the Sooty-headed (P.

griseiceps) and Yungas (P. weedeni) Tyrannulets, forming a clade

sister to Phaeomyias-Nesotriccus (Ohlson et al. 2008, Tello et al. 2009,

Herzog et al. 2012, Harvey et al. 2020). Nests are small cups covered with

lichens for the former two species, yet undescribed in the latter (Belton 1985,

Gonzaga and Castiglioni 2007, R. Ridgely in Hilty and Brown 1986).

The fourth group includes P. burmeisteri (nominate and zeledoni

as sister), the Black-capped (P. nigrocapillus; type of the genus Tyranniscus,

see Cabanis and Heine 1859), Tawny-rumped (P. uropygialis), and

Ashy-headed (P. cinereiceps) tyrannulets. This clade is sister to Ornithion-Camptostoma

(Tello et al. 2009, Harvey et al. 2020). The genetically unsampled but

distinctive leucogonys would presumably be more closely related to burmeisteri

and zeledoni. At the generic level, one alternative would be to treat

all four species in the genus Tyranniscus, whilst P. burmeisteri (together

with zeledoni and possibly leucogonys) might alternatively be put

in the genus Acrochordopus Berlepsch and Hellmayr 1905 (type species Phyllomyias

subviridis Pelzeln 1871, a junior synonym of burmeisteri,

see Hellmayr 1914, 1927). The open cup of burmeisteri and zeledoni contrasts

with the globular nests of Camptostoma and Ornithion (Narosky

& Salvador 1998, de melo Dantas 2006, de la Peña 2016). Unfortunately, no

data is available on the nesting of P. nigrocapillus, P. uropygialis,

or P. cinereiceps (Crozariol 2016). "

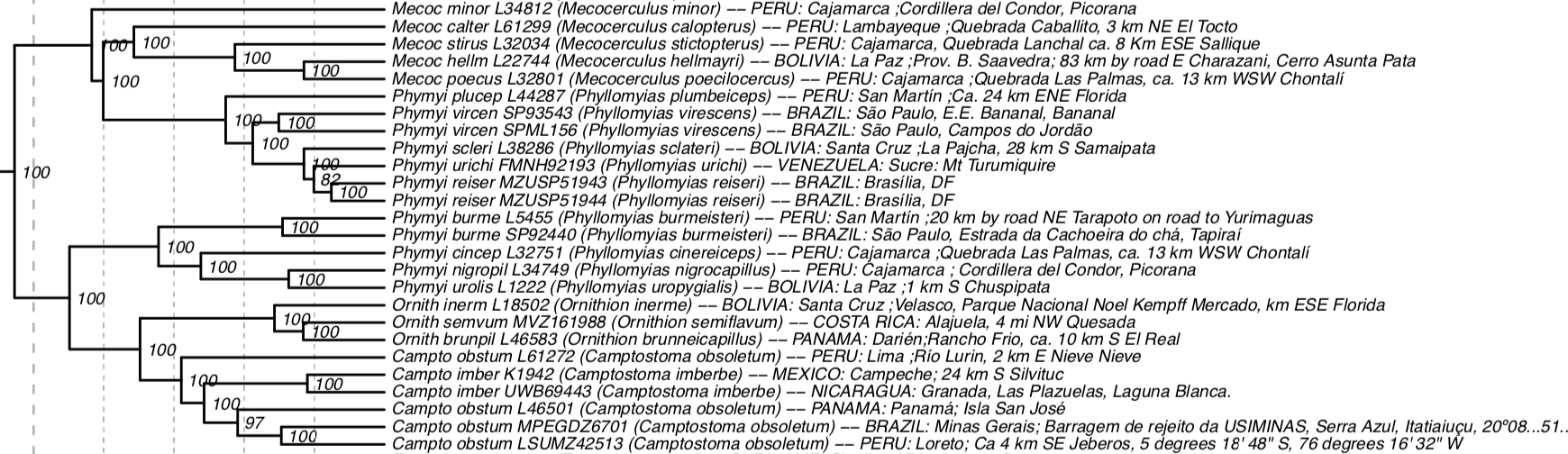

Here is the tree from Harvey et al (2020):

Keeping burmeisteri and

allies in Phyllomyias is not a viable

alternative, although fixing this won´t make Phyllomyias monophyletic (which requires several changes, but this

is a separate issue).

There are two solid options that we could embrace to begin

untangling the generic limits:

A) Broad Tyranniscus: put burmeisteri (including all the taxa

historically contained within it, whether at the species or subspecies level), cinereiceps, nigrocapillus and uropygialis

in Tyranniscus. This option creates a

diverse Tyranniscus, with

genetically, vocally and morphologically quite divergent species.

B) Narrow Acrochordopus: put burmeisteri in Acrochordopus. This seems the conservative option. The rough tarsus

of burmeisteri sensu lato is often

visible even in the field (it does stand out), the genus has been used frequently

in the past, and the taxa in the group are closely knit.

3) Spinoff

on Tyranniscus: If 2B

passes, then we could also move forward and put cinereiceps, nigrocapillus

and uropygialis in Tyranniscus as done well before the

genomic era or the massive Phyllomyias

lump by Traylor (see SACC note 6 above). The three taxa are closely related and

share their high-pitched and similarly patterned vocalizations with a flatter

initial note and some sort of rapid chatter. Although cinereiceps is more different in terms of plumage and was sister to

the other two, it is vocally very similar to nigrocapillus.

Recommendations: we

recommend YES to 1B (depending on discussions on the zeledoni/leucogonys conundrum) and YES to 2B. Likewise, we

recommend a YES to 3.

Voting:

1. Species Limits: Pick

A, B, or C. If one of the options

doesn’t get at least a 7-3 majority on first ballot, then we will do something

more complex.

2. Generic placement:

Pick A or B. Ditto on subsequent ballots

if needed.

3. Tyranniscus

expansion: If you voted for B, then YES or NO on this one

References:

Areta,

J.I., Mangini,

G.G., Gandoy, F.A. & M. Pearman. 2021. Notes on

the nesting of the Rough-legged Tyrannulet (Phyllomyias

burmeisteri): phylogenetic comments and taxonomic tracking of

natural history data. Ornitologia Neotropical 32:56-61.

Parra-Hernández, RM & HD Arias-Moreno (2020a)

Primer registro de Phyllomyias burmeisteri para la cordillera Central de los Andes colombianos, con

comentarios en su variación acústica. Ornitología Colombiana 17: eNB10.

Parra-Hernández, RM, JI

Posada-Quintero, O Acevedo-Charry & HF Posada-Quintero (2020b) Uniform

Manifold Approximation and Projection for clustering taxa through vocalizations

in a Neotropical passerine (Rough-Legged Tyrannulet, Phyllomyias burmeisteri).

Animals 10: 1406.

J. I. Areta & M. Pearman, February 2023

Comments from Lane:

“Part 1: YES to option B,

recognizing burmeisteri and zeledoni as separate species.

“Part 2: YES to option B,

recognizing Acrochordopus for burmeisteri and zeledoni.

“Part 3: YES to recognizing Tyranniscus

for nigriceps, uropygialis, and cinereiceps.”

Comments

from Stiles:

“Species-limits options- A- NO to keeping all in burmeisteri; B- YES to

separating burmeisteri from the leucogonys-zeledoni group;

C- NO for further split of leucogonys and zeledoni on the basis

of vocal data; at least, genetic data needed. (I´m at a bit of a loss here,

because 1A and 1B are mutually exclusive options and in effect recommending

both is confusing). 2. Generic-level options- A- a broad Phyllomyias-NO: at the

least, the Acrochordopus group must be split off; B- Split off the Acrochordopus

group of burmeisteri et al-YES; 3. Spinoff from Tyranniscus

(i.e., resurrect Tyranniscus for nigricapillus et al. leaving the rest

(fasciatus et al.) in Phyllomyias- YES. Thus, the result would be three

genera, no?”

Comments

from Zimmer:

“Part

1. YES on Option B: Two species

treatment, splitting P. zeledoni (including wetmorei, viridiceps,

bunites & leucogonys) from P. burmeisteri, following the vocal

analyses in Parra-Hernandez et al. 2020.

I still think there remains the possibility that more comprehensive

vocal analysis, with broader sampling of calls and songs, might support

recognizing zeledoni sensu stricto as distinct from the other

(South American) taxa in the leucogonys group. I have noted some trilled,

frequency-modulated vocalizations of zeledoni, typically given in

response to playback, or, naturally, during interactions between excited

conspecifics, that I have not heard from leucogonys (sensu lato),

although that may reflect my relative lack of interaction with the latter,

rather than a true distinction. In a

perusal of recordings on the Cornell Birds of the World website, it also seems

as if the spectrographic tracings of songs reveal some fairly consistent

distinctions in note shapes between zeledoni and other taxa in the leucogonys-group

(longer notes, with less-peaked, more rounded centers and longer terminal tails

in zeledoni, versus shorter, more steeply peaked and triangular-shaped

notes with truncated terminal tails in leucogonys). Recognition of zeledoni sensu stricto

as a separate species would also make sense from the standpoint of

biogeography, since its range is confined to the Chiriquí Highlands center of

endemism. All of that being said, I

don’t think the current available evidence supports a 3-way split at this time,

and I also take note of the fact that Gary, who probably has more familiarity with

zeledoni relative to Andean taxa in the leucogonys-group than any

of us (and who treated zeledoni as specifically distinct in Birds of

Costa Rica) is not voting for splitting the two at this time.

“Part

2, Generic placement: YES to option B,

recognizing Acrochordopus for burmeisteri and zeledoni. The currently recognized, broad Phyllomyias

is clearly paraphyletic, and not tenable, as currently constructed. Vocal distinctions and the distinctive, warty

tarsi of the burmeisteri-group are enough, in my opinion, to warrant

further generic separation of those taxa from cinereiceps, nigrocapillus

& uropygialis.

“Part

3, Tyranniscus resurrection: “YES

to resurrecting Tyranniscus for cinereiceps, nigrocapillus &

uropygialis.”

Comments from Claramunt:

“YES to 1.B. split P. zeledoni from P.

burmeisteri.

“YES to

2.B. First impression, a “broad” Tyranniscus (option A), will not be

broad at all as it would include just a handful of species that look very, very

similar. However, I admit that those rough tarsi are so peculiar and

distinctive, plus the light iris that gives them that mad-man look, I think

their separation in Acrochordopus* (totally descriptive, by the way)

makes sense.

“YES to 3,

recognize Tyranniscus for cinereiceps, nigrocapillus, and uropygialis”

[*

from Jobling: “Gr. akrokhordön wart; pous foot”]

Comments

from Niels Krabbe (voting for Pacheco):

“Part 1. YES to option A. Keep a broad burmeisteri. Although the

clusters by Parra-Hernández et al. appear distinctive, they really cover only

two differences: average note length (correlated with pace of notes in song)

and pitch (and with it automatically frequency max, min and span), hardly

enough for species rank. General patterns of songs and calls are identical and

there is overlap in both note length and pitch. Notably, one of four recordings

from W La Paz (ML120908) is intermediate.

“Part 2. YES to a separate genus for burmeisteri (with zeledoni

group). The tarsus is so distinctive.

“Part 3. YES to resurrecting Tyranniscus for cinereiceps,

nigrocapillus & uropygialis. It is only a first step in

cleaning up the polyphyletic Phyllomyias, but at least a step in the

right direction.”

Comments

from Bonaccorso:

962 A. YES.

One species treatment. Definitively, the vocal differences between

burmeisteri and

zeledoni-leucogonys are not as

strong (and may respond to adaptations to local conditions), and the

possibility of more individuals showing intermediate voices (as Niels points

out about (ML120908)) calls for caution and a better understanding of this

aspect in the limits of the distributions. I know that vocal differences are

heavily used here for justifying splits, but it would be important to reinforce

the case with more sampling and some genetic data.

962. B. NO

962 C. NO

962.2. YES

to recognizing Acrochordopus

for burmeisteri. Because a

new name is needed anyway (no name stability possible here), it is best to name

these lineages in a way that reflects their distinctiveness from other

lineages.

962.3. YES to resurrecting

Tyranniscus for

cinereiceps, nigrocapillus, and

uropygialis.

Comments from Mario Cohn-Haft (voting for Jaramillo): “Although

I don't have much direct familiarity with the taxa in question individually and

no comparative experience at all with them in the field, the situation seems to

be nicely laid out for evaluation. judging from the other votes, the most

controversial question is the first one: split or not to split burmeisteri,

and if so in how many spp? The argument

for 3 spp. appears to lack data, and the data currently available argue against

species status for leucogonys. That

will have to wait for new arguments, it seems. No tragedy there. The argument for 2 species is primarily vocal,

but nay-sayers point out that the voices are not spectacularly different and

that there may be vocal intermediates in the geographical middle ground. i

agree that the figures of vocal variation show what could be interpreted as

lots of variation in each and little gap between the 2 vocal types--a gap that

could theoretically be filled by further sampling. However, geographic

proximity does not appear related to vocal trait similarity in the figures, so

it's not intuitively obvious that the intermediate localities, if sampled,

would lead to intermediate vocal types. Furthermore,

the voices sound different to me, especially in pitch (frequency), in a way

that intuitively sounds like "different flycatcher species" to me,

and the lack of any hint of clinal variation approaching a similar-sounding

middle ground reinforces that impression. But finally, if I’m interpreting the

Harvey et al tree correctly, then the 2 "burmeisteri" in it

are actually one a burmeisteri (Brazil) and one a zeledoni/leucogonys

(Peru), and they show the kind of depth in their split comparable to (or deeper

than) most other species in that part of the tree. although I'm no fan of

genetic % limits for taxonomic status, it's hard to imagine members of a cline

that near to one another geographically having that much genetic difference.

“So,

1. YES for

1B: split into 2 species: burmeisteri vs. all other taxa in zeledoni.

2. YES for

2B: place the above 2 spp in genus Acrochordopus. I like recognizing

these smallish clades within the tiny flycatchers as genera. Just because we have trouble seeing (and

hearing) their differences, I think that's simply the allometry of perception;

they're as temporally and proportionately different as genera in larger birds.

3. Then

naturally, YES also for 3: use narrow Tyranniscus for 3 species

currently in broad and sloppy Phyllomyias.”

Comments from Robbins:

“Part 1. Yes to option B. Two species treatment.

“Part 2. Yes to option B. Narrow Acrochordopus.

“Part 3. Yes to Tyranniscus expansion.”

Comments

from Remsen:

“Part 1. Yes to option B, as per recommendation in proposal.

“Part 2. Yes to option B, as per recommendation in proposal.

“Part 3. Yes, for all the reasons given in the proposal”