Proposal (964) to South

American Classification Committee

Note from Remsen: This is a proposal submitted to and rejected

unanimously by NACC. Although the

comments are not yet public, all voters agreed with the synopsis in the

proposal, i.e. almost certainly more than one species is involved, data are

insufficient for resolving the boundaries in this complex group.

Treat Xiphorhynchus aequatorialis

as a separate species from Spotted Woodcreeper X. erythropygius

Description of the problem:

Xiphorhynchus erythropygius is an uncommon

species of upper tropical and lower montane zones from central Mexico (San Luis

Potosí) south through Central America and the Chocoan forests as far south as

southern Ecuador (Marantz et al. 2020). Although its distribution is largely

contiguous, there are multiple breaks in lowland zones. One of these is in

Nicaragua and divides the species into a northern (erythropygius) group and southern (aequatorialis) group, with the species absent from most of the

southern half of Nicaragua (Vallely and Dyer 2018, Marantz et al. 2020). The

northern group is composed of erythropygius

("Sclater, PL", 1860) from north of the Isthmus of Tehuantepec

and parvus Griscom, 1937 to the south

of the isthmus. The southern group is composed of punctigula (Ridgway, 1889) from Nicaragua to central Panama, insolitus Ridgway, 1909, from central

Panama to central Colombia (including the Magdalena Valley), and aequatorialis (von Berlepsch &

Taczanowski, 1884) from central Colombia to southwestern Ecuador. Olive-backed

Woodcreeper (Xiphorhynchus triangularis) of the Andes is part of

this complex, and some authors have considered all taxa to be part of triangularis (see below). Hilty and

Brown (1986) noted that triangularis

is an upper elevation (above 1,500 meters) replacement of aequatorialis on the west slope of the Andes in Colombia.

Taxonomic history:

Ridgway (1911) considered erythropygius monotypic but noted that Berlepsch and Stolzmann

(1896) considered erythropygius to be

a subspecies of triangularis. Ridgway

(1911) split punctigula (with insolitus as a subspecies) as

Spotted-throated Woodhewer, with the following comment: “Somewhat like X. erythropygius,

but color of pileum, back, and under parts greenish or ocherous olive instead

of olive-brown, back without streaks or with very narrow ones on anterior

portion only, and throat spotted rather than barred with dusky.” He gave the

range of punctigula/insolitus as Nicaragua (San Rafael del

Norte) to northwestern Colombia (Río Truando). Berlepsch & Taczanowski

(1884) described aequatorialis as a

subspecies of erythropygius, but aequatorialis was overlooked by Ridgway

(1911) who considered punctigula as

the name for the southern group, although aequatorialis

has priority.

Cory and Hellmayr (1925), perhaps following

Berlepsch and Stolzmann (1896), considered all taxa in the complex to be part

of X. triangularis, with the

following English names for the relevant taxa: Pacific Wood-Hewer for aequatorialis, Truando Wood-Hewer for insolitus (presumably based on the Río

Truando in northern Colombia), Spotted-throated Wood-Hewer for punctigula, and Spotted Wood-Hewer for erythropygius. Cory and Hellmayr’s

comments on the reasoning for lumping all these taxa are worth reproducing here

in full, as they constitute (as far as we can tell) the most comprehensive

comments on plumage variation in the complex, with taxa arranged from

south-to-north:

“Xiphorhynchus triangularis aequatorialis (Berlepsch and

Taczanowski): Differs from X. t.

triangularis in more brownish (less olivaceous) upper parts; plain

(unspotted) crown, with only a few narrow buff streaks on forehead; the much

deeper chestnut rufous of wings and tail spreading also over the lower back;

much deeper buff throat, with the olive markings restricted to small, rounded

apical spots; larger spots on breast and abdomen; uniform horn brown maxilla,

etc.

“Xiphorhynchus triangularis insolitus

appears to have been based on intergrades between aequatorialis and punctigula.

The specimen listed above, obtained by A. Schott on Lt. N. Michler's Expedition

to the lower Atrato [northwestern Colombia], has the back decidedly browner

than the majority in the series of the two forms, though it is very nearly

matched by a female from Bulun, Prov. Esmeraldas, Ecuador, and an unsexed

individual from Chiriqui [Panama]. Markings of throat and spotting on

underparts are exactly as in punctigula.

On the other hand, two skins from Calovevora, Veragua [Panama] hence not far

from the type locality of insolitus

and in the same general region I am quite unable to distinguish from Costa

Rican specimens of punctigula, which,

moreover, is sometimes hard to separate from aequatorialis. Individual variation in these birds is much greater

than generally admitted.

[Regarding a

specimen from San Rafael del Norte in northern Nicaragua] In the amount of

spotting above, this bird is exactly intermediate between punctigula and erythropygia,

but resembles the former in olivaceous coloration and restricted rufous

uropygial area.

“Xiphorhynchus triangularis punctigula. Birds

from Veragua (Calovevora) and Chiriqui [Panama] are identical with those from

Costa Rica. X. t. punctigula is

exceedingly close to X. t. aequatorialis,

but generally distinguishable by brighter olivaceous under parts with smaller

buff spots, more heavily spotted throat, somewhat lighter rufous rump and

wings, etc. Single specimens are, however, not always separable. Through

individual variation, it also intergrades with X. t. erythropygius, of Guatemala. There is notably a specimen from

Chiriqui (at Tring), which combines the greenish olive coloration of punctigula with the heavy spotting, both

above and below, of erythropygia.

Similar examples are no doubt responsible for Panama records of the last named

race.”

In a departure from his typical pattern of

lumping taxa without comment, Peters (1951) split the Choco/Middle American

taxa from X. triangularis (although again without comment), a treatment

maintained by Eisenmann (1955), Wetmore (1972), AOU (1983), and most current

authors.

Multiple authors (e.g., Eisenmann 1955, AOU

1983) noted that the aequatorialis

group is sometimes recognized as a separate species from erythropygius, a treatment formalized by HBW-BirdLife: "[aequatorialis] Hitherto considered

conspecific with X. erythropygius,

but differs in its much less obvious, less teardrop-shaped (and often minimal)

pale streaking on mantle and back (2); darker chestnut tail (1); slightly less

dense pale spotting on underparts (1); higher maximum frequency of whistles in

song after first whistle (2), and overslurred vs downslurred whistles in song

after first whistle (2) (Boesman 2016)."

AOU (1983) account: populations from eastern

Nicaragua southward, occurring commonly in lowland habitats, are sometimes

recognized as a species, X. aequatorialis

(Berlepsch and Taczanowski, 1884) [SPOT-THROATED WOODCREEPER], distinct from X. erythropygius. The widespread South

American species, X. triangularis

(Lafresnaye, 1842), and X. erythropygius

are regarded as conspecific by some authors; they constitute a superspecies.

New information:

Although many studies have sampled Xiphorhynchus erythropygius for

phylogenetic work, most included only a single sample, so are not of use here.

The sole study we have been able to find that included multiple taxa is Weir

(2009), who sampled three individuals and sequenced the mitochondrial locus

cytochrome-b. Samples from El Copé, Panama, and Darién, Panama (both insolitus under current taxonomy), were

sisters, whereas one from the western slope of the Andes (=aequatorialis) was sister to those two. However, no genetic

distances were reported, and the northern erythropygius

group was not sampled. Two samples in Harvey et al. (2020) were both of erythropygius (sensu stricto), whereas two samples in Aleixo (2002) were both of aequatorialis. Multiple studies found erythropygius/aequatorialis as sister to

X. triangularis.

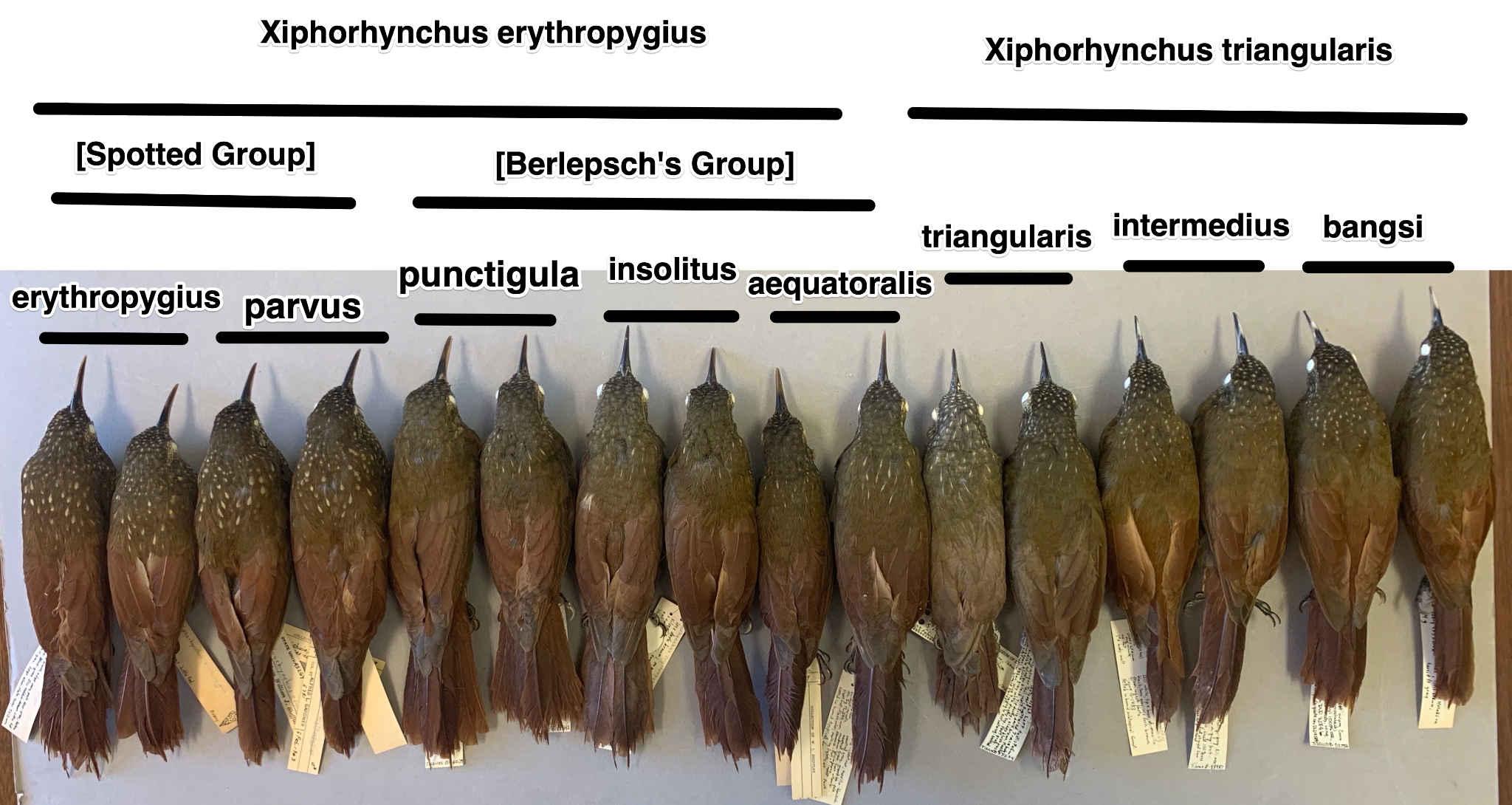

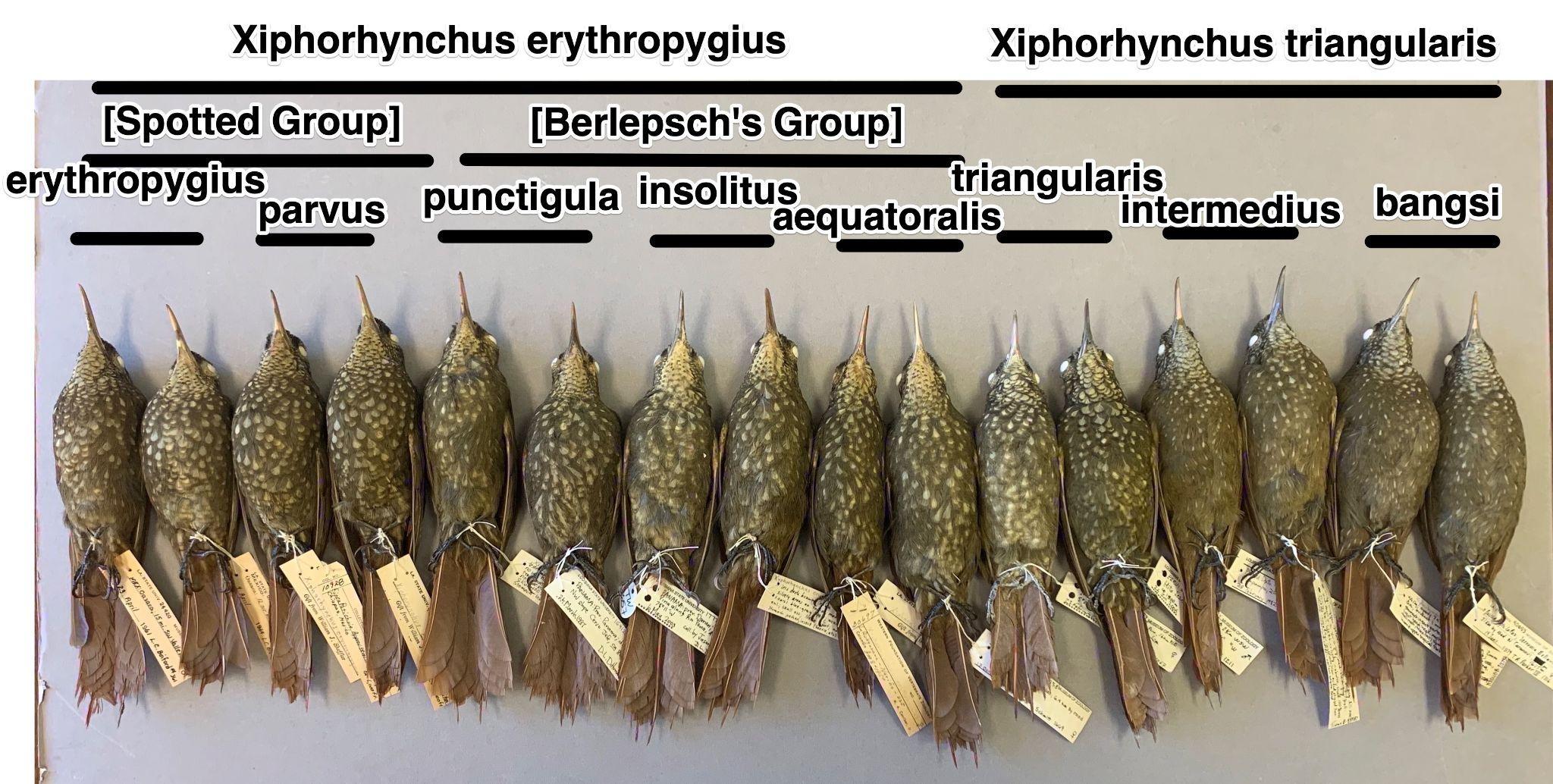

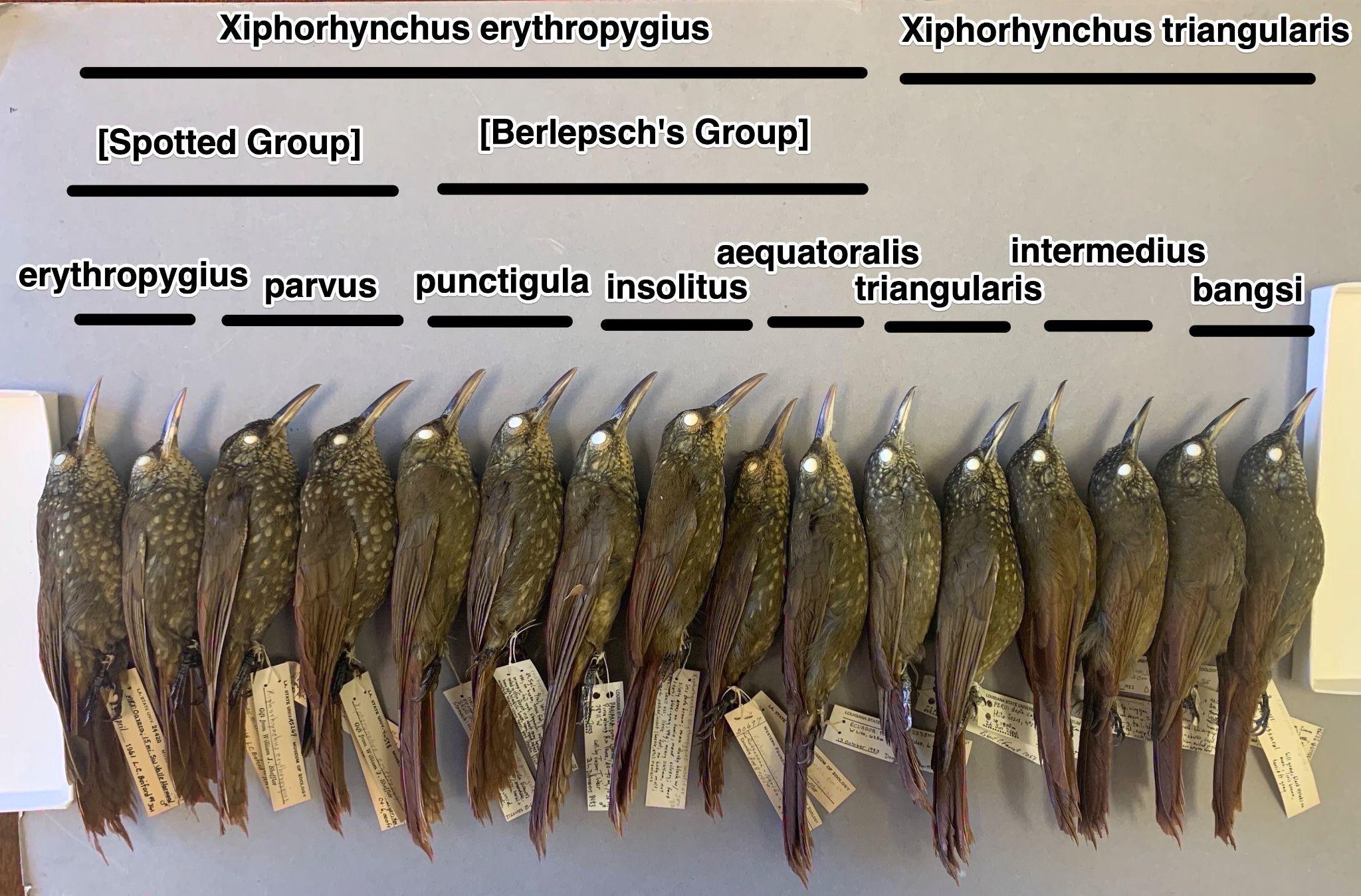

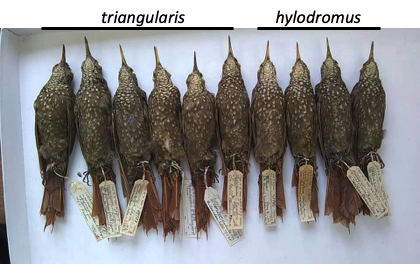

Below are photos of most taxa in the group, from

the collections at the Louisiana State University Museum of Natural Science

(LSUMNS). The two samples of insolitus

are from Darién, Panama, so east of the canal zone.

The specimens at LSUMNS show a confusing

patchwork of plumage variation that do not readily align with current species

limits. The one taxon in the complex not represented in the LSUMNS collections

is the Venezuelan X. t. hylodromus

(see photo in Macaulay Library: https://macaulaylibrary.org/asset/205397931).

The plumage character that most readily

distinguishes X. triangularis from X. erythropygius (as currently defined)

is the scalloped vs spotted throat. However, nominate triangularis (with hylodromus

based on the Macaulay photo above) shares the extensive and broad streaking on

the belly shown by all taxa in X.

erythropygius, and is quite distinct in this regard from the two southern

taxa in X. triangularis (intermedius and bangsi), which show sparse streaks on the belly. Within X. erythropygius, the two northern taxa

(Spotted group) show extensive dorsal

streaking not shown by other taxa, whereas the three southern taxa (Berlepsch’s group) show less crown spotting than

either the Spotted group or X. triangularis, although one specimen

of aequatorialis seems to show some

crown spotting (Figure 1, right hand specimen).

Vocal variation

To our knowledge the only quantitative analysis

of vocal variation within the X.

erythropygius / X. triangularis complex

comes from Boesman (2016), who described vocal variation within X. erythropygius. There is considerable

variation among recognized subspecies across the two currently recognized

species. We are not aware of any rigorous playback studies on this group.

Between the currently recognized subspecies

within X. erythropygius, there are

some slight differences across the putative split in question, but they are

overall quite similar. Both groups

Figure 1: Dorsal view of LSUMNS specimens of X. erythropygius and X. triangularis.

Figure 2: Ventral view of LSUMNS specimens of X. erythropygius and X. triangularis.

Figure 3: Lateral view of LSUMNS specimens of X. erythropygius and X. triangularis.

------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

emit a similar series of 2-4 whistles each of

approximately 0.5–1.0 s in length. However, the erythropygius / parvus group

has little to no frequency modulation in these whistles and is slightly lower

in pitch, starting at ~2.5 kHz and descending to ~1.5 kHz. Among the

Berlepsch’s group of punctigula / insolitus / aequatorialis, the nearest

neighbor X. e. punctigula in Costa

Rica has a similar structure in the series of whistles to the erythropygius / parvus group, but the first punctigula

note has considerably more frequency modulation and higher pitch overall,

starting at ~3.5 kHz and descending to ~2.5 kHz. The songs of X. e. aequatorialis are the most

distinct among these in having much more frequency modulation in each of the

notes, giving them much more of a ‘quavering’ tone compared to the pure

‘whistled’ tone of those in Costa Rica or north of Nicaragua. The quavering

tone seems to extend to the west of the Canal Zone in Panama, but then becomes

decidedly more clear east of the Canal Zone. The type locality of insolitus is in Coclé, Panama, so insolitus would be of the northern vocal

type. Please note that these observations are qualitative and may not stand up

to a more rigorous quantitative analysis of larger sample sizes for vocal

variation within the group.

Boesman (2016) divided X. erythropygius into two vocal groups, a northern one (comprised

of erythropygius and parvus) and a southern one (comprised of

punctigula, insolitus, and aequatorialis),

and his results largely agree with what we describe above. Additionally, he

described the erythropygius group as

having downslurred notes, whereas the aequatorialis

group has overslurred notes. This difference is quite subtle to our ears, and

the strong frequency modulation of aequatorialis

(not present in punctigula and insolitus) and lower pitch of the erythropygius group seem like more

distinct characters. Boesman (2016) stated that the quavering songs change

gradually from north to south, but it seems to us that there may be a clear

break between pure-toned and quavering songs near the canal zone of Panama.

However, some examples even from the northern group seem to have a quavering

tone to some songs.

Macaulay Library holdings for erythropygius / parvus songs from N of Nicaragua:

https://search.macaulaylibrary.org/catalog?taxonCode=spowoo2&mediaType=audio&view=list

https://search.macaulaylibrary.org/catalog?taxonCode=spowoo1&mediaType=audio®ionCode=MX

Macaulay Library holdings for punctigula / insolitus / aequatorialis song from S of Nicaragua:

https://search.macaulaylibrary.org/catalog?taxonCode=spowoo3&mediaType=audio&tag=song&view=list

An example of the quavering song immediately

east of the canal zone in Panama: https://xeno-canto.org/253672

But songs of birds immediately west of the canal

zone in Panama are whistled like those from Costa Rica:

However, some recordings of parvus are somewhat quavering, but otherwise match typical parvus songs in pattern and lower pitch:

https://macaulaylibrary.org/asset/527388

Because X.

triangularis has been considered part of the same species, we have here

provided some recordings from the nearest populations in Colombia. However,

there are not many recordings of the song of this species, and recordings from

farther south in the Andes sound quite different from those in the north. The

short descending whinny of these northern birds is quite different from the

songs of any of the taxa currently considered part of X. erythropygius.

Schulenberg et al. (2007) described the song of

the northern Peruvian populations of X.

triangularis as a “mellow, decelerating, descending series of musical

whistled notes: “whi’we-we-we-we we we

wur”, which agrees with the recordings linked to above, but they noted that

the southern Peruvian (Pasco south) X. t.

bangsi has an additional song, a wiry insistent rising-falling series of

nasal whines: “WHEEEW

who-WHI-WHI-whi-whi-whi” suggesting some vocal variation within X. triangularis. An example of that

latter song is here: https://xeno-canto.org/746087 All song recordings available online from south of the Marañón Valley

seem to match this latter nasal song type.

Very few examples of hylodromus are available online, all in Macaulay, and it is not

clear if these refer to natural songs:

https://media.ebird.org/catalog?taxonCode=olbwoo1&mediaType=audio®ionCode=VE

Effect on AOS-CLC area:

Splitting X.

aequatorialis from X. erythropygius would

result in one additional species for the AOS area. Splitting X. aequatorialis and X. punctigula from X. erythropygius would result in two additional species for the AOS

area.

Recommendation:

We recommend a NO on any splits in this group at this time.

Although we suspect that multiple species may be

involved within what is currently treated as X. erythropygius, it is not clear where best to split taxa as the

different data types are not concordant in their clustering. Vocal data suggest

three song groups within X. erythropygius,

a low-pitched group with clear whistles (erythropygius

/ parvus), a higher-pitched group

with clear whistles (punctigula / insolitus west of the canal zone) and a

quavering song group (aequatorialis

east of the canal zone). The vocal aspect of the BirdLife split is based on

song pitch and downslurred vs overslurred notes but minimized the

diagnosability of the distinctive quavering songs of aequatorialis. However, quantitative analyses are likely necessary

to ascertain whether there is a gradual change in clear-noted to quavering

songs as suggested by Boesman (2016). The differences between the songs of

these groups do not seem as drastic as the differences between X. erythropygius and X. triangularis, and the songs of the

southern X. triangularis (bangsi) seem more distinct than do the

three groups within X. erythropygius.

Plumage data support the distinctiveness of the erythropygius / parvus group based on their extensive mantle and crown streaking.

However, the two southern groups (punctigula

and aequatorialis) show ventral

streaking similar to the northern taxa in X.

triangularis, although they differ from X.

triangularis in throat pattern. We are unable to find consistent plumage

differences between punctigula/insolitus and aequatorialis (which agrees with comments by Cory and Hellmayr

1925, see above) despite apparent differences in song.

This complex is an excellent candidate for

future work. Quantitative analysis of song, plumage, and genetic variation (the

latter of which is lacking) would go a long way towards resolving species

limits in the group.

If any of these splits gain traction, an English

name proposal should be drafted to address the new names. Cory and Hellmayr

(1925) provided some options to work with, which adapted for modern conventions

would be:

• Spot-throated

Woodcreeper for punctigula (which

would include insolitus).

• Spotted Woodcreeper for erythropygius

(although this has now been used for X.

erythropygius s.l., so a new name may be necessary)

• Pacific

Woodcreeper for aequatorialis s.s.

AOU (1983, 1998) used Spot-throated Woodcreeper

for the aequatorialis group (when

separated from X. erythropygius,

although we note that both groups have spotted throats). Clements/eBird gives

Berlepsch’s Woodcreeper as the English name for this group.

Please vote on the following:

1)

Elevate aequatorialis

(with punctigula and insolitus) to species rank (BirdLife

treatment)

2)

Elevate both punctigula

(with insolitus) and aequatorialis to species rank

Literature Cited:

Aleixo, A. 2002. Molecular systematics and the role of the

“várzea”–“terra-firme” ecotone in the diversification of Xiphorhynchus woodcreepers (Aves: Dendrocolaptidae). The Auk

119(3): 621-640. https://doi.org/10.1093/auk/119.3.621

AOU. 1983. Check-list of North American Birds. The species of birds of

North America from the Arctic through Panama, including the West Indies and

Hawaiian islands. 6th edition. American Ornithologists’ Union.

AOU. 1998. Check-list of North American Birds. The species of birds of

North America from the Arctic through Panama, including the West Indies and

Hawaiian islands. 7th edition. American Ornithologists’ Union.

Berlepsch, G. H. von, and L. Taczanowski. 1884. Liste des Oiseaux

recueillis par MM. Stolzmann et Siemiradski dans l’Ecuadeur occidental.

Proceedings of the Zoological Society of London 536-577.

Berlepsch, G. H. von, and J. Stolzmann. 1896. On the ornithological

researches of M. Jean Kalinowski in central Peru. Proceedings of the Zoological

Society of London 322-388.

Boesman, P. 2016. Notes on the vocalizations of Spotted Woodcreeper (Xiphorhynchus erythropygius). HBW Alive

Ornithological Note 82. In: Handbook of the Birds of the World Alive. Lynx

Edicions, Barcelona. (retrieved from http://www.hbw.com/node/931976).

Cory, C. B. and Hellmayr, C. E. 1925. Catalogue of birds of the

Americas, part IV. Field Museum of Natural History Zoological Series Vol. XIII.

Chicago, USA.

Eisenmann, E. 1955. The species of Middle American birds. Transactions

of the Linnaean Society of New York. Vol. VII.

Harvey, M.G., A. Aleixo, C.C. Ribas, and R.T. Brumfield. 2017. Habitat

association predicts genetic diversity and population divergence in Amazonian

birds. American Naturalist 190: 631-648.

Hilty, S. L., and W. L. Brown. 1986. A Guide to the Birds of Colombia.

Princeton University Press.

Marantz, C. A., J. del Hoyo, N. Collar, A. Aleixo, L. R. Bevier, G. M.

Kirwan, and M. A. Patten. 2020. Spotted Woodcreeper (Xiphorhynchus erythropygius), version 1.0. In Birds of the World

(S. M. Billerman, B. K. Keeney, P. G. Rodewald, and T. S. Schulenberg,

Editors). Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, NY, USA.

https://doi.org/10.2173/bow.spowoo1.01

Peters, J. L. 1951. Check-list of birds of the world. Vol. VII. Museum

of Comparative Zoology at Harvard College.

Ridgway, R. 1911. The birds of North and Middle America. Part V.

Bulletin of the United States National Museum. No. 50.

Schulenberg, T. S., D. F. Stotz, D. F. Lane, J. P. O’Neill, and T. A.

Parker III. 2007. Birds of Peru, revised and updated edition. Princeton

University Press.

Vallely, A. C. and D. Dyer. 2018. Birds of Central America. Princeton

University Press.

Weir, J. 2009. Implications of genetic differentiation in Neotropical

montane forest birds. Annals of the Missouri Botanical Garden 96(3): 410-433. https://doi.org/10.3417/2008011

Wetmore, A. 1972. The Birds of the Republic of Panamá. Part

3.-Passeriformes: Dendrocolaptidae (Woodcreepers) to Oxyruncidae (Sharpbills).

Smithsonian miscellaneous collections, v. 150.

Oscar Johnson and Nicholas A. Mason, February

2023

Note

from Remsen on voting: Although I didn’t put this in the proposal title, note

that there are two parts, which require separate votes:

964.1.

Elevate aequatorialis (with punctigula and insolitus) to species rank (BLI treatment)

964.2. Elevate both punctigula (with insolitus)

and aequatorialis to species rank

Note

from Remsen on English names: if this passes, a separate proposal would be

needed; see discussion of possibilities above.

Comments

from Remsen:

“I’m not voting on this one – I have asked Jorge to take my slot. What I said on the NACC version was ‘No for all the reasons given

in the proposal (which is outstanding).

As noted in the proposal, this is a complex situation that requires a

rigorous, formal, published study to change species limits, and it seems clear

that changes are needed, even from the largely anecdotal information presented

so far.’

Comments from Areta: “NO, following the rationale in the

excellent proposal. After hearing to several vocalizations, I could not find

any clearly diagnostic feature of each taxon. There seems to be a lot of

geographic variation, and some vocalizations sound quite intermediate. Until

someone performs a more rigorous vocal study, I prefer to keep these as one

species. Xiphorhynchus triangularis

is also in need of a taxonomic review, of course.”

Comments

solicited from Curtis Marantz (voting for Pacheco): “NO. I am in agreement with the

recommendation to recognize no splits at this time. I should begin by noting that this is a

mostly highland complex for which I have very little field experience, and as

such, I am not in as good a position as I am with the lowland taxa to comment

on the variation that I see or hear in the photos and recordings, or in past

treatments of the group. It has also been a very long time now since I last

looked at any of this, because even though they have contacted me regarding

some of the HBW accounts, this was not one of them, so I have had no input

whatsoever on anything in the newer HBW account beyond what I wrote back in 2001,

and to be honest, I cannot even recall now if I wrote the taxonomic section for

this entry (though I think I did write this one).

“This said, the plumage variation is rather complex and

confusing. Moreover, I am not sure how

important things like the extent of spotting or the tone of olive or brown in

the plumage is for species-level differences.

These seem more like subspecies-level differences to me. I feel better about discrete differences,

such as those shown between the Central American and Amazonian populations of

the Barred Woodcreepers, and especially so when they correspond to very

striking vocal differences. I suppose

the first thing one would want is a detailed analysis based on many specimens

of each taxon to see how consistent these plumage differences really are.

“With regard to the vocal differences, my recommendation would be

that a much larger sample is required, not only to examine individual and

regional variation in the song of the species, but also to examine the

repertoire more carefully to ensure that you are not comparing songs with

calls. Even within the sets of recordings from smaller areas, I am hearing

sufficient variation to conclude that both songs and calls are included in

these samples, but I do not know these birds sufficiently well to determine

which sounds are homologous. In the Xiphorhynchus guttatus complex,

which I know best, there are several different calls and extensive variation in

the songs, some if it motivational and not regional. From listening to the

various recordings linked, it becomes immediately apparent that the recordings

from the Macaulay Library show a break between the clear and quavering songs to

be well south of where the species-groups are divided, with recordings from

Costa Rica and those from Ecuador having rather different songs despite both

being treated under the category Spotted Woodcreeper (Berlepsch's). I also found some recordings in which the

initial element was quavered but the others were clear, which may suggest to me

that there is a motivational aspect to the quavered elements.

“So, in the end, I do agree that there are interesting patterns

evident, and possibly even more than one species involved, but as with many

such cases in woodcreepers, I feel that it is premature, given the information

available, to make any taxonomic decisions. Then again, I am also one who tends

to be of the opinion that taxonomy should remain as stable as possible unless

there is a really compelling reason to make a change. If not, the result is

that others will conclude that the bodies making these decisions do not really

have a solid grasp on what they are doing and are just trying to jump on the

newest suggestions based on incomplete data.”

Comments

from Robbins:

“I vote NO for elevating any of the taxa currently in

Xiphorhynchus erythropygius to species level for the reasons that

Oscar and Nick have detailed in their thorough proposal. It appears that there

is considerable variability in all character states mentioned and genetic data

are lacking across the entire complex. Yes, likely more than one species

involved in the complex, but clarifying what taxonomic changes need to be made

will require much more data.”

Comments from Lane: “NO. As a believer in the concept of subspecies, I see the

variation demonstrated within X. erythropygius here as in line with my

expectations of furnariid subspecific variation.

As an aside, I would point out

that the proposal made the comment that within X. triangularis "All song recordings available online

from south of the Marañón Valley seem to match this latter nasal song type."

This is not true, as illustrated by https://macaulaylibrary.org/asset/531434and https://macaulaylibrary.org/asset/534618. The

wiry song described in Schulenberg et al. seems to be genuinely limited to more

southerly Peruvian and Bolivian populations; central Peru seems poorly sampled

for voice of this species. Nevertheless, the well-sampled San Martín area

population lacks this wiry song, seeming more aligned with the north of the

Marañon voice type. This taxonomic issue is best saved for some future

proposal, however.”

Comments

from Stiles:

“NO, on current evidence in which genetics, plumages and perhaps vocalizations

appear not to concur.”

Comments

from Jorge Pérez-Emán (voting for Remsen): “This proposal aims to treat the

subspecies Xiphorhynchus erythropygius

aequatorialis as a separate species (aequatorialis)

from X. erythropygius. It also

elaborates on the potential for an additional species (punctigula), the relationship of these taxa with X. triangularis, and the geographical

differentiation of triangularis (just

briefly). The evidence put into the proposal is thorough and provide a good

picture of geographical variation both in plumage patterns and vocalizations.

Based on such information, it is clear we don´t have enough data to understand

species limits in this complex, so my short answer will be NO and NO to both

parts of the proposal (two or three species, when considering punctigula also as a different species).

I elaborate a bit more below, and provide additional complementary information

on molecular data, thanks to Brant Faircloth who extracted mitochondrial

sequences from UCEs data from the suboscines project (from Harvey et al. 2020)

to provide molecular data of the northern erythropygius

group.

“1.

Differences in plumage coloration and size are minor among recognized

subspecies. However, on top of that and as clearly indicated in the proposal,

the large amount of individual variation shown by X. erythropygius specimens compromise any pattern of geographical

variation previously used to define taxon limits. Such awareness for individual

variation is not new and was emphasized by previous researchers (Cory and

Hellmayr 1925, Griscom 1937), some even indicating the potential effects of

foxing in museum specimens and age in such variation (Wetmore 1972, Griscom

1937). Even with a short series, pictures of LSUMNS specimens taken by Oscar

and Nick reveal plumage differences between two specimens of aequatorialis (differences that suggest

even potential diagnostic patterns are variable). Additionally, Cory and

Hellmayr (1925, and also Griscom 1937) highlighted different aspects of this

variation suggesting the presence of intermediates between punctigula and parvus

(specimens from San Rafael del Norte, Nicaragua, and Chiriqui, Panama). In

fact, I am not quite sure when the San Rafael del Norte specimen was

transferred to punctigula, but

Griscom (1937) already included there. The same pattern was highlighted by

these authors (as noticed in the proposal) for aequatorialis and insolitus

in Colombia, where limits of distribution are unclear and some localities were

considered as dubious (about what taxon was present) by M. de Schauensee (1950,

lower Cauca Valley, La Frijolera).

“2.

Variation in vocalizations seems to better differentiate some groups but is not

clear cut. Analyses from Boesman (2016) and this proposal found a major break

between the northern and southern group (erythropygius/parvus vs. punctigula/insolitus/aequatorialis, respectively), though

diagnostic vocal characters differed between both analyses. However, the most

different vocalization corresponded to aequatorialis

compared to other taxa and there is individual variation that makes difficult

to understand differences between punctigula

and insolitus or even between these

taxa and the northern group taxa (as highlighted in this proposal). A pattern

of variation worth mentioning is the suggested break of vocalization

similarities at the Canal zone, with birds east of it similar to aequatorialis and birds west of it more

similar to punctigula and the

northern group. This pattern suggests insolitus

vocalizations group with different taxa depending on location relative to the

Canal zone. With much variation and no certainty about the cause of these

differences (as pointed out by Curtis), deciding how to group these taxa is

difficult. The proposal also makes clear that patterns presented are

qualitative and require formal analysis with larger data. Unfortunately,

Boesman (2016) does not indicate sample size for his analysis, making difficult

to evaluate how consistent are the reported differences.

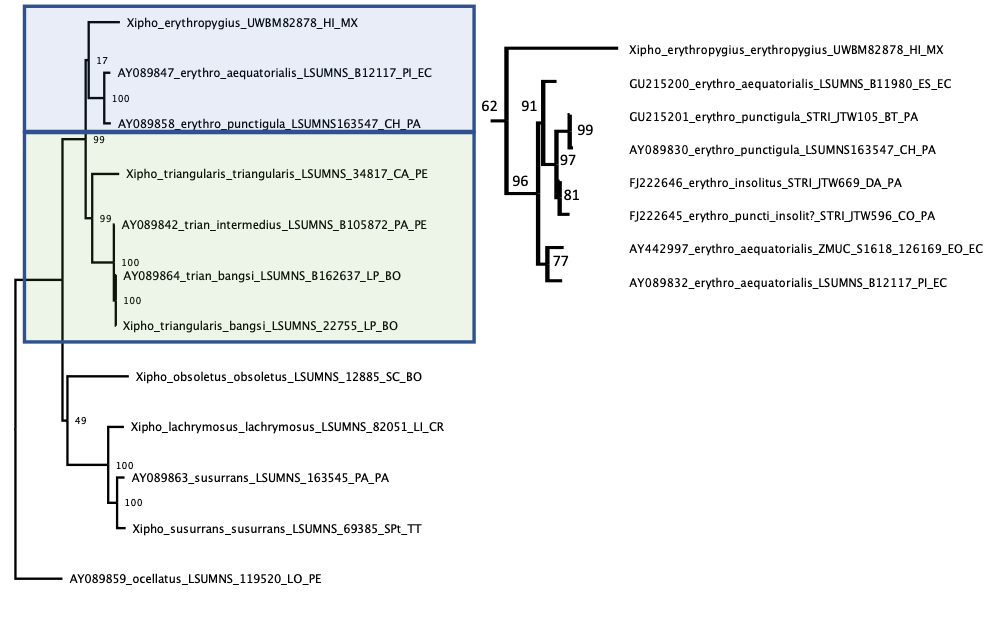

“3.

I gathered all available molecular information (both from GenBank and Brant

Faircloth) to complement this proposal with some hints on genetic variation,

doing a quick phylogenetic analysis and some molecular pairwise comparisons.

Previous phylogenetic information showed triangularis

to be the sister taxon of erythropygius

(Derryberry et al. 2011; Harvey et al. 2020), a relationship that holds

here with increasing taxon representation for each species (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Maximum Likelihood hypothesis of

phylogenetic relationships of Xiphorhynchus

erythropygius species complex. In the left figure is the hypothesis based

on both ND2 and cytochrome b genes, while the right figure shows only the

relationships within X. erythropygius

based on just cytochrome b gene. Color boxes highlight relationships within

(and between) both X. erythropygius

and X. triangularis. Sequences

obtained either from GenBank (identified by their code starting with AY, GU or

FJ) or from the UCEs data of the suboscine phylogeny (Harvey et al. 2020, mitochondrial genes

courtesy of Brant Faircloth). Numbers at nodes represent bootstrap data

obtained from 1000 pseudoreplicates of the fast algorithm of RAxML. Localities: HI_MX = Hidalgo, Mexico; LI_CR = Limón, Costa Rica; CH_PA =

Chiriquí, Panama; BT_PA = Bocas del Toro, Panama; CO_PA = Coclé, Panama; PA_PA

= Panama, Panama; DA_PA = Darién, Panama; SPt_TT = Saint Patrick, Trinidad and

Tobago; ES_EC = Esmeraldas, Ecuador; PI_EC = Pichincha, Ecuador; EO_EC = El

Oro, Ecuador; CA_PE = Cajamarca, Perú; LO_PE = Loreto, Perú; PA_PE = Pasco,

Perú; LP_BO = La Paz, Bolivia; SC_BO = Santa Cruz, Bolivia.

“Molecular

data allow for a complementary view of geographical variation from a different

character set. An important add-on to previous analyses is the availability of

one sample of erythropygius from

Hidalgo, Mexico (erythropygius).

Haplotypes from this specimen are sister to the rest of haplotypes (punctigula, insolitus, aequatorialis;

parvus not included) with large

genetic divergence between them (around 5% in ND2, and 4% in Cytb). Such

genetic divergence and sister relationship is in agreement with suggestions

that this taxon is a candidate for a separate species (or aequatorialis, including the southern group, being a separate

species). Variation within the aequatorialis

group is somehow complex. The most complete available molecular data is for the

cytochrome b gene, and it shows a non-monophyletic aequatorialis with high support and some structure suggesting

western Panama and Costa Rican taxa conforming a group that separates from

another one that includes both east and west Canal zone populations (Darien and

Coclé, Figure 1). Whether the Coclé specimen is insolitus is unclear as it comes from the Pacific slope of Coclé

(El Copé National Park), perhaps less than 30km to one of the closest

localities associated to punctigula (Chitra,

Panama; Wetmore 1972). These sequences are very similar (about 0.3% divergent)

and differed a bit when compared to western Panama/Costa Rica sequences (about

0.6%), but still very similar. Sequences from aequatorialis diverge in average 1.4% from these punctigula/insolitus but are more similar to the Darien one (1.2%) than the

ones from the west Canal zone (1.6%; including the Coclé sequence). However,

these are very similar numbers which might not mean much based on the small

sample size.

“4.

Even when we could be tempted to make some conclusions from the plumage,

vocalizations and molecular patterns at hand, geographical differentiation and

species/taxon limits are difficult to understand as geographical sampling is

far from being representative and different characters vary differently with

geography as pointed in the proposal. There are unclear geographical breaks

based on plumage variation (with some intermediates found throughout Central

America and northern Colombia, based on the literature) and vocal data suggest

a complex differentiation in Panama (breaking potential insolitus in two potential groups, west and east of the Canal zone)

with the largest variation associated to aequatorialis.

Molecular data show a large differentiation of erythropygius compared to the southern group, which does not

differentiate much genetically. However, data from specimens collected west and

east of the Canal zone (Darien and Coclé) group together, contrasting with

vocalization data. It is worth to highlight the fact that the area from Colón

to Veraguas (east and west Canal zone) have been identified as a potential

suture zone in which morphology and molecular data are not congruent between

each other (McLaughlin et al. 2020 Cotinga 42:77-81; McLaughlin et al. 2023,

bioRxiv). This could explain the lack of correlation among all sets of

characters in this area and make it hard to understand, with current data, the

relationships between punctigula, insolitus and even aequatorialis. If we add the lack of data for the region of

potential contact between insolitus

and aequatorialis or punctigula and parvus (and between the northern group subspecies), we realize we

are far from reaching a conclusion regarding species/taxon limits in this

complex.

“5.

To expand on the discussion of X.

triangularis, plumage variation seems to be larger between triangularis (and hylodromus) and intermedius/bangsi. In the proposal, Oscar and Nick

did not have access to skins of hylodromus.

I am including two pictures (taken by Miguel Lentino from Colección Ornitológica

Phelps) in which you can see the large similarity between both taxa. Wetmore

(1939, Smith. Misc. Coll. 98) described hylodromus

as “brighter olive brown above; expose

surfaces of secondaries darker, less reddish brown; under surface lighter, more

greenish olive, more abundantly spotted, the spot lighter colored; throat

decidedly lighter, with the dark marginal lines on the feathers reduced in

width (underlining mine).” Many of these differences are really tenuous

and with a series such as the one in the picture (Figure 2), showing large

individual variation throughout the distribution of the species in Venezuela, a

reevaluation of geographical differentiation is needed to recognize (or not)

the presence of two subspecies. The major difference is on the throat, lighter

in hylodromus, part of the effect

given by the reduction of dark marginal lines on the feathers (Figure 2, right

picture). Regarding distribution of these taxa in Venezuela, and perhaps a

consequence of the tenuous differences between them, Hilty (2003) indicated hylodromus has a distribution along the

northern Cordillera of Venezuela extending to the northeastern Andean

Cordillera (Lara and Trujillo). However, these specimens were suggested to be

either intermediate in plumage coloration between both taxa (Phelps and Phelps,

ms.) or should be better placed in triangularis

(M. Lentino, pers. comm.). Unfortunately, Hilty (2003) did not provide any

criteria to understand how he assigned localities to these taxa.

Figure

2. Pictures of Xiphorhynchus triangularis

triangularis and X. t. hylodromus

from Venezuela (pictures taken by Miguel Lentino from Colección Ornitológica

Phelps). On the left, ventral view of a short series of specimens showing the

large similarity between these taxa. The major difference between them is the

lighter throat in hylodromus shown in

the right picture.

“Molecular

data and phylogenetic analyses (Figure 1) also suggest a major break

potentially associated to the Huancabamba Dry Valley or Marañon river.

Sequences were available from Cajamarca, Peru and Zamora-Chinchipe, Ecuador

(not shown in the figure), north of Marañon river (both triangularis, diverging by just 0.2%), and, south of the Marañon,

from Pasco, Peru (intermedius) and La

Paz, Bolivia (bangsi), also very

similar genetically (0.3-0.4%). These data show that there might be a large

break between triangularis and both intermedius/bangsi but the geographical range of triangularis is largely unsampled. On the other hand, sequences of intermedius and bangsi are very similar (suggesting either current gene flow or

recent divergence) compared to vocalizations that appear to be largely

different (based on southern records (potentially bangsi) of Tom Schulenberg. However, the geographical distribution

of these vocal differences and the real nature of it (i.e., larger vocal

diversity, frequency of each vocalization in the repertoire) is unclear as Dan

Lane recordings from San Martin, Peru, suggest a similar vocalization of this

population (intermedius) to triangularis and we don´t know where, if

any, is the break between these type of vocalizations.

“In

summary, the proposal clearly indicates that even when phenotypic

differentiation of X. erythropygius

suggest more than one species within this group, the complexities of this

variation, the lack of correlation among characters, and the lack of formal

analyses, sample sizes and geographical representation, do not allow to make

any definitive conclusions at this point. The same goes for X. triangularis, included in the

proposal as historically considered to form a species or species complex with X. erythropygius.”

Comments

from Zimmer:

“NO. As laid out nicely in this proposal, we simply don’t have enough

information in my opinion to make sense out of the observed variation. Sample sizes and geographic breadth of

genetic data seems insufficient to do much with, and plumage variation, while

notable at the extremes, seems to not be concordant with currently recognized

taxa, and intra-taxon variation looks, in some cases, to exceed or equal

between-taxon variation. Vocal

distinctions are much more impressive to me, as I would expect to be the case

with tree-hugging, forest-interior inhabiting, suboscines of a group in which

plumage seems to be evolutionarily conservative, and in which minor

distinctions are unlikely to be used by the birds themselves for sorting one

another out. As Curtis pointed out in

his comments, it is especially important that any quantitative vocal analysis

compares homologous vocalizations from one taxon to the next, and in the linked

audio recordings, I’m seeing some instances where the vocalizations being

compared are not clearly homologs. This

was particularly the case with the referenced recordings of X. triangularis

hylodromus from Venezuela, all of which I would label as calls and not

songs. It has been some years since my

last field exposure to members of the erythropygius-triangularis

complex, but my recollection is that the two currently recognized species

(Spotted and Olive-backed) always struck me as vocally distinct (at least in

their songs), and that vocal differences from one place to another in Spotted

Woodcreepers were a matter of degree, not of kind. I also remember individual Spotted

Woodcreepers giving altered songs in response to playback, and those

alterations involved differences in number of notes, pace, and degree of

frequency modulation, the latter altering the quality of the vocal elements –

something I’m certain would have been visible in spectrograms. It is my experience that woodcreepers, in

general, tend to give all kinds of twisted, qualitatively different

vocalizations in response to playback (as is also the case with the various Sclerurus

species of Leaftossers), and therefore, any attempts at quantitative vocal

analyses need to be of spontaneously vocalizing birds and homologous

vocalizations. All of that being said, I

will say that my personal experience with Spotted Woodcreepers is mostly from

Mexico to c Panama (west of the Canal Zone), and it is those birds whose voices

I would describe as differing in only subtle ways from one another. I was struck by how consistently different

all of the songs of aequatorialis that I listened to from the sound

archives (mostly from Ecuador) sounded from the relatively pure, unmodulated

whistles of birds from w Panama, Costa Rica, and points north and west from

there. Nothing from those northern

populations sound anything, to my ears, like the tremulous, quavering songs of aequatorialis,

nor do the tracings from the spectrograms look anything alike. So, I think there’s definitely some

significant vocal differences between songs of triangularis versus the erythropygius

group and the aequatorialis group, and between the erythropygius

group and the aequatorialis group.

But, at this point, that’s a qualitative judgement on my part, and one

that still hasn’t been rigorously quantified with geographically broad samples

of homologous, spontaneously given vocalizations across the various taxa. Until we have that, I would favor sticking

with the status quo. Also, although I

clearly think it is premature at this point to be talking about English names

for any splits, I do want to point out that the suggested (in the Proposal) English

name of “Spot-throated Woodcreeper” for X. punctigula/insolitus is

already taken by Certhiasomus stictolaemus!”

Comments

from Jaramillo:

“NO. This is a highly complex situation that requires

much more rigorous data to sort it out. Looking at that line up of specimens is

eye-opening … that is a good amount of variation morphologically there. That

alone makes me think something more than one species is present, but which

ones, why, based on what data independent of morphology? I don't think we are

close on this one yet to understanding what is going on.”

Comments from Claramunt: “NO. First I have to

disagree with previous comments: plumage variation is suggestive of

species-level differences, in my opinion. At least the LSU series shows three

clearly diagnostic groups, easily distinguishable, that would match the

proposed three-species classification. Those differences are not minor in the

context of Xiphorhynchus woodcreepers that tend to be very conservative

in plumage patterns. But of course, the situation may be more complex and a

detailed study of geographic variation (including also songs and DNA) is

clearly necessary here before making decisions about species limits.”