Proposal (965) to South

American Classification Committee

Note from Remsen: This is a proposal submitted to and rejected

unanimously by NACC. Although the

comments are not yet public, all voters agreed with the synopsis in the

proposal, i.e., lack of information from the contact zone and minimal vocal

differences.

Treat Poliocrania

maculifer as a separate species from Chestnut-backed Antbird P. exsul

Description of the problem:

Poliocrania exsul is an understory antbird

found in tropical lowland forests of Central America and the Chocó, from

Honduras to Ecuador (Woltmann et al. 2020). In its current treatment, it

consists of five subspecies that can be broadly split into two groups based on

the presence or absence of white spots on the wing coverts (Woltmann et al.

2020). The northern exsul

("Sclater, PL", 1859) group lacks wing spots and is found in Central

America, barely reaching northern Colombia on the Caribbean slope (near Acandí; Hilty and Brown 1986), and consists of the

subspecies exsul (Caribbean slope

from Costa Rica to western Panama), niglarus (Wetmore, 1962; central Panama to northern

Colombia), and occidentalis (Cherrie,

1891; Pacific slope from Honduras to western Panama). The wing-spotted maculifer (Hellmayr, 1906) group is

found in the Chocó and reaches into the Magdalena Valley of northern Colombia

and into eastern Panama in the lowlands of Darién Province on the Pacific slope

(Woltmann et al. 2020). This group consists of the southern subspecies maculifer and the northern subspecies cassini (Ridgway, 1908). Females of the maculifer group are also distinguished

by brighter chestnut underparts.

Hellmayr (1906) described maculifer as a subspecies of exsul

(also considering occidentalis as a

subspecies), with the primary differences being the “fulvous-white apical spots

on all the wing coverts” in both sexes, and a shorter tail (40-44 mm in male maculifer vs. 47-52 mm in males of occidentalis and exsul). Ridgway (1908), describing cassini just two years later, considered both maculifer and cassini to

be valid species, each as distinct from exsul,

with the only rationale being a footnote under cassini that says, “This form is evidently quite distinct

specifically from Myrmeciza exsul Sclater”. In Ridgway’s description

of cassini, he stated that:

“This form agrees with M. maculifer in its relatively very short tail (as compared with M. exsul and M. exsul occidentalis), and also in having all the wing-coverts marked with a terminal white spot, and may be

only subspecifically distinct; but the coloration is so conspicuously different

that at present, or until actual intermediates are found, I prefer to designate

it by a binomial.”

However, Chapman (1917), with a larger series of

specimens, noted that intermediates between maculifer

and cassini occurred over a broad

region, including some localities containing specimens resembling both taxa,

and gave the approximate boundary between the two taxa as the upper Atrato

River (southwest of Medellín, Colombia) with cassini found north into the Magdalena Valley. Chapman (1917) also

noted that specimens of cassini from

eastern Panama showed no signs of intergradation with exsul from the Canal Zone and westward and considered maculifer (with cassini as a subspecies) to be a separate species from exsul. Cory and Hellmayr (1924)

considered all taxa to be part of exsul

(without comment), a treatment followed by Peters (1951), Eisenmann (1955), and

most later authors. It is surprising that Cory and Hellmayr (1924) gave no

reasoning for lumping maculifer/cassini

with the northern exsul group, as

these authors were careful to cite the broad intergradation between maculifer and cassini described by Chapman (1917) and were typically very

thorough in their taxonomic treatments.

However, it appears that individuals with white

spots in the wings extend far beyond the contact zone in the central Darién

Province of Panama. Wetmore (1962), in describing niglarus (of the northern exsul group) from Chimán

in far eastern Panamá Province (near the Darién border, geographically about

halfway between the specimens available to Chapman) noted that some individuals

of this subspecies showed intermediate amounts of wing spotting: “The wing

coverts are plain in most individuals of this race, with the white spotting

typical of M. e. cassini and M. e. maculifer found only casually in a

few. Specimens from the middle Chucunaque Valley,

near the mouth of the Rio Tuquesa, are intermediate

between the new form and cassini,

which ranges through the rest of the lowlands of the Tuira

basin”. These latter localities are in the central Darién province of Panama.

AOU (1983) followed this treatment, noting that “Populations from eastern

Panama (eastern Darién) south to western Colombia have sometimes been regarded

as a distinct species, M. maculifer (Hellmayr, 1906) [WING-SPOTTED

ANTBIRD], but intergradation occurs in western Darién.” Ridgely and Gwynne

(1989) noted that some birds with wing spots can be found as far west as Cerro

Jefe on the Caribbean slope of the Canal Zone.

BirdLife International split the maculifer group from the exsul group based on the following

rationale: P. maculifer "[h]itherto considered conspecific with P. exsul, but (although voices appear identical) differs in its

white spots on wing-coverts (3); brighter underparts in female (1); paler grey

underparts in male (1); olive-chestnut vs dark chestnut upperparts in both

sexes (ns1); shorter tail (effect size -4.9, score 2); narrow zone of

hybridization (2)."

Woltmann et al. (2020) described the song as

“Two or three full, mellow whistles. […] The first note is more emphatic, with

a deliberate, but short (1 s) pause before the next note, which may or may not

be of lower pitch. In the 3-note song it is the first syllable that is repeated

(the second note sometimes at a higher pitch) and never the last syllable.”

They noted that maculifer may give

the three-note song more frequently than the two-note song.

New information:

Very little. Other than an excellent summary of

geographic variation in the Poliocrania

exsul complex in Woltmann et al.

(2020), I can find no recent publications with taxonomic relevance on this

group.

The Harvey et al. (2020) suboscine phylogeny

included two samples of P. exsul, but

both were of the subspecies occidentalis,

one from Limón on the Caribbean coast of Costa Rica, and the other from Coclé,

Panama, the latter of which is near the contact zone with niglarus. However, no samples were

from the southern maculifer group.

Below are a series of photos of specimens at the

Louisiana State University Museum of Natural Science (LSUMNS), courtesy of Anna

Hiller and Nicholas Mason (Figs. 1-3).

Figure 1. Seven specimens from the maculifer group. The upper five are of maculifer and the lower two are of cassini. Note that one of the males of maculifer has the wing coverts obscured by flank and scapular

feathers, such that any wing spots (if present) are not visible.

Figure 2. A series of specimens of exsul (upper 6) and occidentalis

(lower 3) showing the lack of wing spotting and overall darker coloration of

both sexes in comparison with the Chocó taxa.

Figure 3. Females of (L to R) exsul, cassini, and two maculifer, showing especially the brighter underparts of the southern taxa.

Although most photos available online (Macaulay)

from Darién Province seem to agree with the LSUMNS specimens (e.g. https://macaulaylibrary.org/asset/48605081), two from central Darién seem to show limited white spotting (https://macaulaylibrary.org/asset/494631221 and https://macaulaylibrary.org/asset/343711101) and although the photo is not clear, one may lack spotting (https://macaulaylibrary.org/asset/223776311). However, topotypical niglarus is found only a short distance (about 80 km) to the

west of most of these individuals (https://macaulaylibrary.org/asset/202364931), so the contact zone seems to be quite limited in extent. A female

from the Canal Zone in Panama shows the darker underparts of the exsul group but has small white spots on

the wing coverts: https://macaulaylibrary.org/asset/35110341. I found photos of two adult males in Costa Rica

(out of ~1,000 photos available in the Macaulay

Library) with very limited white spots on the median coverts:

https://macaulaylibrary.org/asset/178037841 and https://macaulaylibrary.org/asset/54813581. All individuals in Macaulay from Ecuador and Colombia had clearly

spotted wing coverts.

There appear to be no published analyses of

vocal differences between taxa, aside from the assertion in Woltmann et al.

(2020) that maculifer gives 3-note

songs more frequently than the exsul

group. In listening to recordings, I was able to find multiple recordings of

3-note songs in maculifer and cassini, and although I found only a few

examples of 3-note songs in the exsul group,

they do exist.

• maculifer, 3 note: https://macaulaylibrary.org/asset/28482

• exsul, 3-note: https://macaulaylibrary.org/asset/55245961

However, 2-note songs were also common in maculifer, e.g.: https://macaulaylibrary.org/asset/499635721

And most from

occidentalis and exsul were

2-note: https://macaulaylibrary.org/asset/338492511

Although some recordings from Costa Rica sound a

bit higher-pitched, I am unable to detect consistent vocal differences between

the northern exsul and southern maculifer groups. However, a formal

analysis is desirable.

Effect on AOS-CLC area:

Splitting maculifer

from exsul would result in one

additional species for the AOS area.

Recommendation:

I recommend a NO on splitting maculifer

from exsul based on apparent

intermediates in the Darién, a lack of published studies on this contact zone,

and apparently minimal vocal differences. Based on the data in Wetmore (1962),

it appears that there is a (perhaps narrow) hybrid zone in the central/western Darién,

although the exact width and evolutionary dynamics of this hybrid zone have not

been investigated. Other than the brief mention by Ridgely and Gwynne (1989),

there appear to be no data on whether there are intermediate phenotypes on the

Caribbean slope of eastern Panama and northern Colombia. Given the utility of

vocal divergence as a metric for species-level differences between antbird

species (Isler et al. 1998), the minimal vocal differences (in just a scan of

recordings available online, formal analysis needed) between the maculifer and exsul groups also indicate that these are best treated as

subspecies for now.

If maculifer

is split from exsul, then an English

name proposal should be drafted to address the new names, preferably in

coordination with the SACC. Clements/eBird uses the common names of

Chestnut-backed Antbird for exsul and

Short-tailed Antbird for maculifer. I

prefer Wing-spotted Antbird for maculifer,

as suggested by AOU (1983), as this is the more obvious morphological character

separating this group. Chestnut-backed Antbird has been used for both the exsul group and for the entire complex,

with no other name published for the exsul

group.

Literature Cited:

AOU. 1983. Check-list of North American birds. The species of birds of North

America from the Arctic through Panama, including the West Indies and Hawaiian

islands. 6th edition. American Ornithologists’ Union.

Chapman, F. M. 1917. The distribution of bird-life in Colombia: a

contribution to a biological survey of South America. Bulletin of the American

Museum of Natural History 36.

Cory, C. B., and C. E. Hellmayr. 1924. Catalogue of birds of the

Americas, part III. Field Museum of Natural History Zoological Series Vol.

XIII. Chicago, USA.

Eisenmann, E. 1955. The species of Middle American birds. Volume VII.

Transactions of the Linnaean Society of New York.

Harvey, M. G., Bravo, G. A., Claramunt, S., Cuervo, A. M., Derryberry,

G. E., Battilana, J., Seeholzer, G. F., McKay, J. S., O’Meara, B. C.,

Faircloth, B. C., Edwards, S. V., Pérez-Emán, J., Moyle, R. G., Sheldon, F. H.,

Aleixo, A., Smith, B. T., Chesser, R. T., Silveira, L. F., Cracraft, J., …

Derryberry, E. P. 2020. The evolution of a tropical biodiversity hotspot.

Science 370(6522): 1343–1348. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aaz6970

Hellmayr, C. E. 1906. Critical notes on the types of little-known

species of Neotropical Birds. Novitates Zoologicae 13 (2): 305-352.

Hilty, S. L. and W. L. Brown. 1986. A guide to the birds of Colombia.

Princeton University Press, Princeton, New Jersey.

Isler, M. L., P. R. Isler, and B. M. Whitney. 1998. Use of vocalizations

to establish species limits in antbirds (Passeriformes; Thamnophilidae). Auk

115:577–590.

Peters, J. L. 1951. Check-list of birds of the world. Vol. 7. Museum of

Comparative Zoology at Harvard College.

Ridgway, R. 1908. Diagnoses of some new forms of Neotropical birds.

Proceedings of the Biological Society of Washington 21:191-196.

Ridgely, R. S., and J. A. Gwynne, Jr. 1989. A guide to the birds of

Panama. Princeton University Press, Princeton, New Jersey.

Wetmore, A. 1962. Systematic notes concerned with the avifauna of

Panamá. Smithsonian Miscellaneous Collections 145 (1): 1-14.

Woltmann, S., R. S. Terrill, M. J. Miller, and M. L. Brady. 2020.

Chestnut-backed Antbird (Poliocrania

exsul), version 1.0. In Birds of the World (T. S. Schulenberg, Editor).

Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, NY, USA.

https://doi.org/10.2173/bow.chbant1.01

Oscar Johnson, February 2023

Note

from Remsen on English names: if this passes, a separate proposal would be

needed; see discussion of possibilities above.

Remsen’s comments on the NACC version:

“NO, resoundingly, for all the reasons given in the

proposal. I basically stopped reading the proposal in detail when I came to

BLI’s own analysis: “BirdLife International split the maculifer group

from the exsul group based on the following rationale: P. maculifer

"[h]itherto considered conspecific with P.

exsul, but (although voices appear identical) …. “ [boldfacing by me]. This is a great example of the

fundamental problem with the phenetic, point-based Tobias et al system. All

characters are not alike. Thanks to the work of Mort and Phyllis Isler, Bret

Whitney, and many others, vocal differences are known to be the key predictor

of free gene flow or lack of it in parapatric and sympatric antbirds. Plumage

differences are of minimal consequence as barriers to gene flow to these

antbirds, so why should it make a difference to us if our criteria for species

rank are rooted in cessation of free gene flow?”

Comments from Areta: “NO. The case is very weak, given the

lack of a proper vocal analysis in the face of vocal similarity, the reduced

plumage differences, and the fact that the hybrid zone is scored as favoring

the split (baffling in its own).”

Comments from Robbins: “I vote NO for treating Poliocrania

exsul maculifer as a species for all the reasons that Oscar underscored in

the proposal.”

Comments

from Gustavo Bravo (who has Remsen’s vote): ““No.

After inspecting a series of 12 specimens (5 females, 5 males) specimens from

PN Katíos housed at the Instituto Humboldt Bird

Collection, females seem to exhibit variance in wing-covert spots ranging from niglarus-like birds (almost no spots) to cassini-like

(prominent spots). Also, there are birds with intermediate spots being more

like maculifer. Males, on the other hand, seem to resemble cassini.

Keeping in mind that the geographic location of PN Katios

is roughly where the three subspecies are predicted to meet, it makes sense

that birds therein represent intermediates. The critical question is how far

these intermediates expand from Katíos and the Darién

region. Except for a female from Acandí (ca. 70 km N

of Katíos) with conspicuous niglarus

plumage (no spots, darker underparts), I don’t have available specimens from

nearby regions. The closest localities with specimens available to me (male

only) are Nuquí (coastal Chocó) and Alto Baudó (Baudó

River Valley), which are ca. 250 km S, and plumage there seems to be good maculifer.

Also, a quick inspection of a handful of spread wings of males along the

Pacific coast of Colombia seems to suggest clinal variation in the size and

density of wing-covert spots, but, of course, this should be taken with a grain

of salt given the tiny sample size and the sparse geographic sampling.

Regarding underparts, all females from Katíos (except

for one) are decisively lighter than females from the exsul group.

“Therefore, given the current

suggestions of plumage intermediates, the lack of consistent vocal variation,

and the lack of detailed genetic and morphological analyses with sampling

around the putative zone of phenotypic intergradation, I vote NO on this split.

This one is an obvious case in which a thorough sampling would inform the

taxonomy and the extent of gene flow between populations from South and Central

America meeting in this region. Given what we know of other taxa with similar

distributional patterns, I would not be surprised if, in the future, we end up

having enough evidence to support this split.”

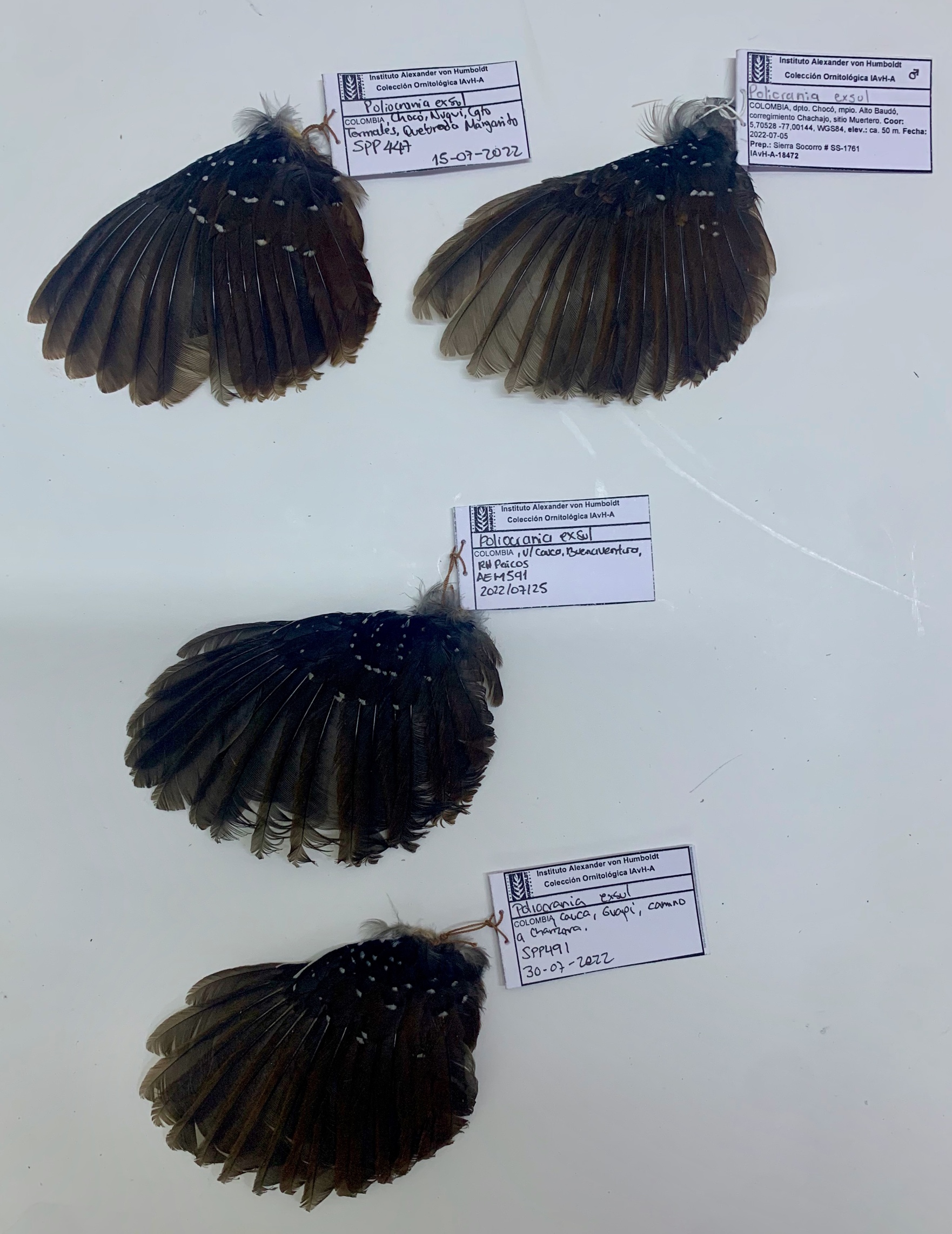

“Photo 1. Female plumage

variation in PN Katíos and comparison with niglarus, cassini, and maculifer.

“Photo 2. Male plumage variation

in PN Katíos and comparison with cassini, and maculifer.

“Photo 3. Male spread wings

showing wing-covert spot variation along the Colombian Pacific Coast. Top row Nuquí and Alto Baudó, Chocó; middle row Buenaventura, Valle

del Cauca; bottom row Guapi, Cauca.

Comments from Lane: “NO on this split. It appears that all evidence available

now suggests that these two groups are not sufficiently distinct to warrant a

split.”

Comments from Stiles: “NO, on equivocal vocal evidence and

intergradation in Panama. Regarding the former, with practically daily

experience with exsul in Costa Rica, I can confirm that the 2-note song

is somewhat more frequent, but the 3-note version is by no means rare; and when

I whistled the 2-note song in Tumaco (extreme SW Colombia), the local Poliocrania

birds responded and approached me giving both the 3-note song and the 2-note

version (at least once). Definitely anecdotal, but certainly not evidence for a

2-species split!”

Comments

from Zimmer:

“NO, for all of the reasons mentioned in the Proposal and by others in their

comments. I have seen, photographed, and

tape-recorded many P. e. cassini in the lowlands of Darién, Panama, and

while they are consistently somewhat different in plumage from their Canal Zone

counterparts (this particularly true of female cassini, whose underparts

are largely bright rufous), both calls and songs are very similar. I remember paying particular attention to the

vocalizations of cassini on my first several encounters, and aside from

the already discussed differences in the frequency of delivery of 2-note songs

and 3-note songs (relative to exsul), the songs of cassini struck

me as having a slightly different tonal quality, but this did not, to my ear,

rise to the level of species-grade distinctions, and both the single-note

agonistic calls and the longer multi-note calls sounded to me to be identical

to the homologous calls of birds from the Canal Zone.”