Proposal (966) to South

American Classification Committee

Note from Remsen: This is a proposal submitted to and rejected

(4 to 8) by NACC. Although the comments

are not yet public, the NO voters agreed with the synopsis in the proposal, i.e.,

insufficient data to make formal changes in a complex situation, although

multiple species likely involved.

Split Mionectes olivaceus into two species, M. olivaceus and M. galbinus

Background: Mionectes olivaceus is a small fruit-eating flycatcher with a range

from Costa Rica to eastern Venezuela and Bolivia along lower montane slopes and

nearby lowlands. The species was

described in 1868 by Lawrence from Costa Rica. There are 5 recognized

subspecies all of which were originally described as subspecies of olivaceus.

New Information: Boesman (2016) examined the voices of the

various subspecies of olivaceus and

concluded that there were 4 vocal groups. One was the nominate subspecies, olivaceus, found in eastern Costa Rica

and western Panama. A second consisted of the taxa hederaceus and galbinus.

The subspecies hederaceus occurs from

Veraguas, Panama, south largely on the western side of the Andes to southern

Ecuador whereas galbinus is known

from the Santa Marta Mountains of Colombia.

The third vocal group consists of venezuelanus

from northern Colombia and northern Venezuela and fasciaticollis on east slope of Andes from southern Colombia to

Bolivia. The fourth group is from Santander, Colombia and is not clearly

associated with any of the recognized taxa.

Boesman evaluated the groups using the Tobias (2010) criteria and scored

olivaceus versus the other taxa as 8.

He scored hederaceus/galbinus versus venezuelanus/fasciaticollis as 6.

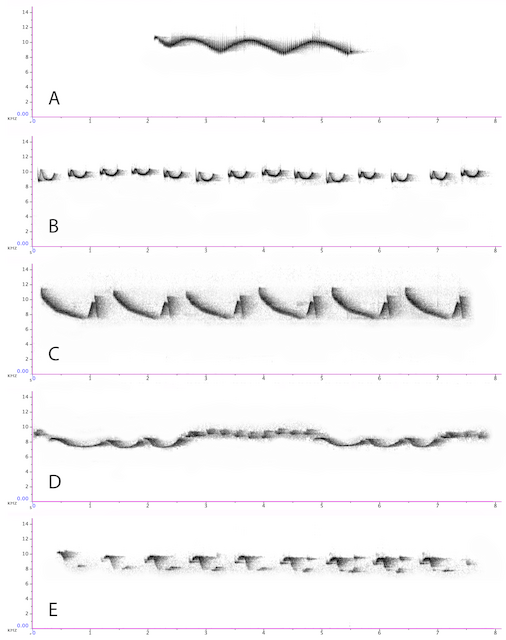

The

sonograms here are from the Birds of the World account (Fitzpatrick et al

2020). A is nominate canfasciaticollis/ venezuelanus, D is

the Santander population of uncertain subspecies, and E is a single recording

from the far eastern end of the northern Venezuela mountain, which currently

would be assigned to venezuelanus. Recordings of songs from populations in the

Perijá Mountains and Trinidad do not seem to be available.

These

songs are squeaky and extremely high pitched, basically between 8 and 10

thousand MHz I personally cannot hear

the sounds on recordings of nominate olivaceus

(at least through my computer) at all, and am not hearing the other

populations’ vocalizations well. The

literature describes these songs as insect- or hummingbird-like.

Morphological

variation among the five subspecies is minor. The main variation is in the

brightness of the green upperparts, the brightness and tone of yellow on

abdomen, the extent of streaking and paleness of streaking. None of this

variation would be apparent in the field. In del Hoyo and Collar (2016), they

assign some points toward the Tobias criteria score based on plumage. However, I would say, from examining

specimens and the discussion in Fitzpatrick et al (2020), that olivaceus is not at the extreme in any

of the characters varying across the 5 subspecies. It is generally pale and bright, but to my

eye, galbinus is the palest and

brightest of these taxa, whereas hederaceus

is overall the dullest.

At

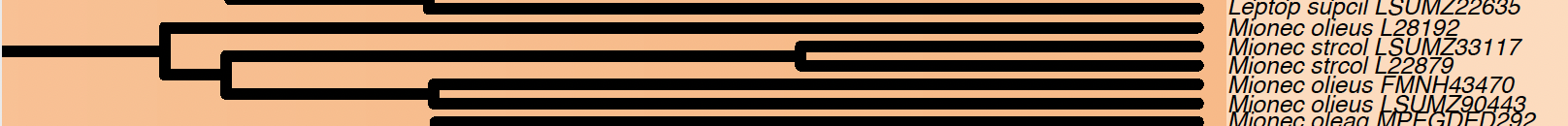

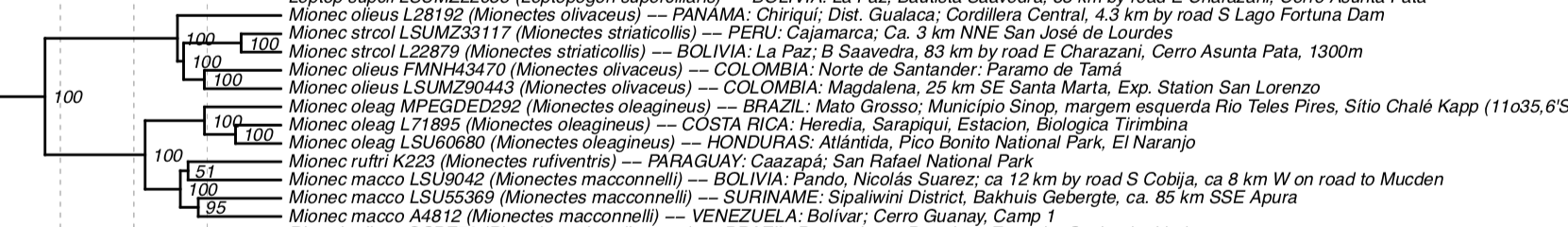

the time of del Hoyo and Collar (2016) there was no genetic evidence available

for this complex. However, Harvey et al

(2020) examined multiple samples of olivaceus

as well as the other species of Mionectes. In their analysis, Mionectes olivaceus was paraphyletic, with nominate olivaceus, sister to a clade with Mionectes striaticollis and samples

corresponding to galbinus and venezuelanus. M.

striaticollis is a similar species broadly sympatric with olivaceus in South America, overlapping

with the subspecies hederaceus,

fasciaticollis, and venezuelanus.

Recommendation: This is a complicated issue. I think it is very likely there are multiple

species within the current Mionectes

olivaceus. Splitting nominate olivaceus is supported by a distinctive

voice and the genetic evidence that it is not sister to the rest of the

species. If NACC did this, we would add

a species to the overall list, because olivaceus

occurs in Costa Rica and western Panama, and hederaceus representing Mionectes

galbinus occurs in central and eastern Panama. However, it seems likely that there are

multiple species to be recognized in galbinus. Unfortunately, I think we currently lack

sufficient information to define the various species that would be left in galbinus. There has not been genetic analysis done at a

relevant scale for that question, and many populations (including galbinus) do not have recordings in

Xeno-canto or Macauley collections. One vocal group (D from Santander above) has

not been clearly assigned to a named taxon. For NACC, the issue is that the

name galbinus may not be applicable

in the end to the populations in Panama.

This case reminds me of Schiffornis

turdinus for SACC. A proposal to

split in 2007 failed to pass, but with additional data, in 2011 a new proposal

to split Schiffornis turdinus into 5

species did pass.

My

weak recommendation is a NO vote, awaiting further evidence that will allow us to define more

clearly the multiple species that likely make up Mionectes olivaceus.

English

names:

Del Hoyo and Collar (2016) use Olive-streaked Flycatcher for M. olivaceus and retain Olive-striped

Flycatcher M. galbinus. Because the ranges are very uneven in size

with M. galbinus much more widespread

than M. olivaceus, I think the use of

Olive-striped Flycatcher for M. galbinus

is justified under our English name criteria.

Further, given that the splitting up of galbinus into two or more species seems likely eventually, we (or

SACC) would have to coin new names for the daughter species at a later time. I

recommend using Olive-streaked Flycatcher for Mionectes olivaceus and Olive-striped Flycatcher for Mionectes galbinus if we decide to split

these two groups. These are the names used by del Hoyo and Collar 2016, and

used for the groups corresponding to the species recognized by del Hoyo and

Collar in the Birds of the World account (Fitzpatrick et al. 2020).

References:

Boesman, P. F. D. 2016.

Notes on the vocalizations of Olive-striped Flycatcher (Mionectes olivaceus). Birds of the World

Ornithological Note 117. In: Birds

of the World. Cornell Lab of Ornithology,

Ithaca, NY. (retrieved from birdsoftheworld.org/bow/ornith-notes/JN100117

on 25 March 2022.).

del

Hoyo, J., and N. J. Collar. 2016. HBW and BirdLife International Illustrated

Checklist of the Birds of the World. Volume 2. Passerines. Lynx Edicions,

Barcelona, Spain.

Fitzpatrick, J. W., J. del Hoyo, N. Collar, E. de Juana, G. M. Kirwan,

and A. J. Spencer. 2020. Olive-striped Flycatcher (Mionectes

olivaceus), version 2.0. In Birds of the World (T. S.

Schulenberg and B. K. Keeney, Editors). Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, NY,

USA. https://doi.org/10.2173/bow.olsfly1.02

Harvey, M. G., G. A.

Bravo, S. Claramunt, A. M. Cuervo, G. E. Derryberry, J. Battilana, G. F.

Seeholzer, J. S. McKay, B. C. O’Meara, B. C. Faircloth, S. V. Edwards, J.

Pérez-Emán, R. G. Moyle, F. H. Sheldon, A. Aleixo, B. T. Smith, R. T. Chesser,

L. F. Silveira, J. Cracraft, R. T. Brumfield, and E. P. Derryberry. 2020. The

evolution of a tropical biodiversity hotspot. Science 370:1343-1348.

Tobias, J.A., N.

Seddon, C. N. Spottiswoode, J. D. Pilgrim, L. D. C. Fishpool, & N. J.

Collar 2010. Quantitative criteria for species delimitation. Ibis 142:724-746.

Doug Stotz, February 2023

Note

from Remsen on English names: if this passes, a separate proposal would be

needed; see discussion of possibilities above.

Comments from Remsen (as in my NACC

comments):

“NO. Tough call for me. As noted in the proposal, M. olivaceus

is a paraphyletic taxon certainly consisting of multiple species, and Boesman’s

preliminary analysis indicates vocal differences consistent with species rank

for several populations. But this is a

case in which a piecemeal approach seems unwise, especially in the case of galbinus-hederaceus,

because we don’t have genetic data from what would be the taxon in the NACC

area (hederaceus) (Harvey et al. included only 3 subspecies of M.

olivaceus) and because according to the proposal, galbinus and hederaceus

are the most divergent taxa in terms of plumage. Boesman and Harvey et al. have set the stage

for a future, thorough analysis that will allow us to sort all this out in

terms of taxonomy.

“One could make the argument that it is more

important to split olivaceus into two species to remove the problem of

maintaining a paraphyletic species than it is to wait to sort out all the

details, which affect mainly extralimital taxa (South America) anyway. I understand that rationale, and I am

convinced from the published sonograms and measurements of the vocal parameters

in Boesman (2016) that the NACC area has two species-level taxa (nominate olivaceus

vs. hederaceus). I am not opposed to piecemeal taxonomic change, would

support it if we were reverting to a prior treatment rather than a novel one,

and would support that split if the data behind it were solid. But are they solid? The genetic data for paraphyly are based on

Harvey et al. 2020, excerpted below:

“Note that

only 5 individuals were sampled: 2 M. striaticollis and 3 M.

olivaceus. The proposal notes that

the 3 olivaceus samples represent 1 sample each of nominate olivaceus,

galbinus, and venezuelensis (the latter two the sisters in the

tree). That only leaves out Boesman’s

Santander vocal group* (which evidently cannot be assigned to subspecies

yet). But it also leaves out two

critical subspecies, including the one from the NACC area: hederaceus. Splitting everything from nominate olivaceus

as one species assumes that hederaceus and fasciaticollis group

with galbinus and venezuelensis rather than olivaceus. That is the most likely outcome based on

biogeography, but it is not a certainty.

Hederaceus is the closest taxon (parapatric evidently) to

nominate olivaceus. We are

assuming hederaceus groups with galbinus because of Boesman’s

vocal analysis (more on that later), but the proposal noted that they are at

opposite extremes of plumage variation in the complex, so that is a

concern. Even fasciaticollis, the

most distant taxon from nominate olivaceus, occurs as close as southern

Colombia, and cannot be dismissed completely as a potential disjunct, sister

taxon to nominate olivaceus.

“And then there is

another potential problem: there are two additional unsampled named taxa that

were subsumed into venezuelensis on the say-so of Fitzpatrick in HBW

without any real analysis: pallidus Chapman, 1914 (TL = Buena Vista,

4500 ft., above Villaviscensio, Meta, Colombia), and meridae Zimmer,

1941 (type loc = near Mérida, Venezuela).

Mel Traylor, in his Tyrannidae chapter in “Peters” 1979 recognized both

subspecies. Traylor gave the range of pallidus

as “Upper tropical and lower subtropical zones of Eastern Andes of Magdalena

and northern Meta, Colombia” and of meridae as “Subtropical zone of

northwestern Venezuela from western Zulia and Falcon to Táchira, and Norte de

Santander and Boyacá in adjacent northeastern Colombia.” Note that according to the proposal Norte de

Santander is region from which Boesman described a separate vocal group, and so

I strongly suspect Fitzpatrick unjustly sunk meridae; here’s what

Fitzpatrick said: “pallidus …. and meridae … are indistinct,

intermediate forms within a cline, both treated as synonyms of venezuelensis.” That’s it.

It should be noted that Fitzpatrick synonymized a number of tyrannid

subspecies based on statements like this, and that some of these synonymized

taxa are actually vocally distinct (e.g. Phyllomyias griseiceps, which

he treated as monotypic).

“As far as Boesman’s

vocal data go, his N for nominate olivaceus was 6 and for hederaceus,

19. So that looks solid, and just

eyeballing the sonograms suggests to me that these are the most different of

the vocal groups. Then, for galbinus

from the Santa Martas, N=1. On the basis

of that one recording, Boesman groups galbinus with our hederaceus. Again

eyeballing the sonograms, that single recording does bounce around like hederaceus,

but to my eye, the note shapes (lopsided “U”) of galbinus look more like

Andean venezuelensis and fasciaticollis than they do those of hederaceus

….Which actually makes more sense biogeographically in terms of

relationships. Boesman does not have a

specific metric for note shape, by the way.

“So, in summary, we

would be making a novel taxonomic change based on 5 individual genetic samples

that do not include the critical taxon hederaceus, which happens to be

the one of the largely South American group represented in the NACC area. Yet we would be assigning the species name galbinus

to that species, and hederaceus would be a subspecies of galbinus. And that taxonomy would be based on Boesman’s

analysis of a single recording, the sonogram of which to my eye looks more like

the Andean taxa, not hederaceus.

Further, our case for paraphyly is actually weak with respect to the two

taxa in our area because we don’t have a genetic analysis that included hederaceus. Am I the only one queasy about all this? Yes,

we’ve got two species in the NACC area, and we can punt the other problems to

SACC, but it just seems awfully sloppy and laden with compound assumptions. Imagine the egg-on-face fallout if there is

something wrong with our current understanding once we have genetic and vocal

data from all 5 (or 7) taxa? I don’t see

why we should take that risk.

“* my

downloaded version of Boesman (2016) states that this vocal group is from

Caripe, Venezuela, and thus pertains to venezuelensis, so I’m not sure

what’s going on here except that Doug must have access to a more recent

revision.”

Comments from Areta: “Harvey et al. (2020) show that olivaceus is deeply

paraphyletic (Panama sample would be olivaceus,

Colombian samples would be galbinus

from Santa Marta and hederaceus

from Tamá):

“The

problem I see is that by splitting the nominate olivaceus from the rest, we would have a new

use for the name galbinus

to be applied to what seems to be at least 2-3 species, thereby leading to a

new faulty taxonomy.

“The

variation in vocalizations of these Mionectes

requires more thorough quantification. In a rapid examination in XC and in the

NACC proposal, the differences in sounds do not match the species limits

outlined by BirdLife, and because so much variation remains unexplained, I

don´t think a good case has been made to adopt this split, even when it seems

quite clear that there are multiple species within M. olivaceus

as currently circumscribed.

“I

am seriously concerned by these “express” splits. I have no doubt that olivaceus is a different

species, but as a taxonomic committee, I think that we should be worried about

deeper issues, such as the new application of the name galbinus (a Santa Marta

endemic?) at the species level for another array of species. Then this rather

unsatisfactory usage will spread, only to be changed sooner than later. As

such, I prefer to stick to known historical errors of wide application instead

of incurring in a new kind of error affecting more taxa (e.g., venezuelanus would in all

probability have now been erroneously considered to pertain to olivaceus AND galbinus). To me, we do a

disservice to stability by accepting splits such as this one, and this is why

to me not all the "clear splits" are equally acceptable. We have to

deal with species-level entities and their names, and this is where things get

muddy. In this case, I don´t think that the piecemeal approach to taxonomy is

adequate. This complex needs to be sorted in one movement, lest we create a

large number of ephemeral taxonomies and ensuing confusion.”

Comments from Lane:

“NO, largely for the reasoning Van puts forth. Whereas I suspect

splits will be necessary once we gain a better understanding of the various

taxa involved (both molecularly and vocally), the taxonomy makes me leery of

splitting using the wrong daughter names (much as was almost the case with

Herpsilochmus rufimarginatus and

frater). As it happens, I literally made a recording yesterday in the

Santa Martas-- as “bycatch” in the background of

another recording (and thus ID not visually confirmed)--that has the same

vocalization that Niels identified as M. o.

galbinus (XC235896). My recording

uploaded here: https://macaulaylibrary.org/asset/534205891.

“I note that XC235896 has in its notes that the singer was *not

seen* and so I don’t know what grounds Niels used to identify that voice as

M. o. galbinus! However, I used Niels' recording to play back

to a bird I was watching later yesterday, and it seemed

briefly to respond

positively, approaching me once before returning to foraging (and not showing

interest again despite more playback). Given the lack of representation of key

taxa in a phylogeny, the lack of confirmation of ID of several key recordings (such

as the XC recording above), and the reluctance to have to backtrack on species

names if the results of those future studies contradict what has been proposed,

I would rather stay at status quo until things are clearer.”

Comments from Robbins: “NO. Clearly, multiple species

are involved, but as Van and Dan point out we need additional information on a number

of facets of this complex before any splits are made.”

Comments from Stiles: “NO for splits at this time; the plumages

of all are very difficult to tell apart, and unfortunately, my post-malarial

ear is deaf to the songs, so I’d like to see a more thorough genetic analysis

with birds also recorded and if possible, a colorimetric analysis to get this

one sorted out.”

Comments

from Del-Rio (who has Pacheco vote): “NO. I would like to see a more

complete study of this complex, including sound recordings and molecular data.”

Comments from Zimmer: “NO. The molecular

data are pretty clear that M. olivaceus, as currently constituted, is

paraphyletic. But Boesman’s vocal

presentation, while a good start, leaves the question of how many splits should

be recognized as the taxonomic equivalent of a “jump ball”. I would want to see a more broadly sampled,

detailed, quantitative vocal analysis, not just a handful of spectrograms, no

matter how much those tracings would appear to differ.”

Comments from Claramunt: “NO. Vocal

and genetic data really suggest that the taxon in Costa Rica and W Panama is a

different species, but I agree with others in that more evidence is needed, in

particular, data about birds in central and eastern Panama.”

Additional

comments from Lane (11 Feb 2025): “As a PS to the above comments, I

just returned from the Santa Martas (again) and I believe the mystery of the Krabbe recording that was

the sole documentation of the voice of taxon galbinus has been solved:

that voice is actually song of Anisognathus melanogenys! This makes

perfect sense now, as it is a COMMON voice on the San Lorenzo ridge (2600 m),

where I have not seen Mionectes at all! The identification was made by

local guide Roger Rodriguez, who says he has visually confirmed the identity.

So, given that the voice of galbinus is now not documented at all, we

are dealing with yet more gaps in knowledge about this complex than before.”