Proposal (968) to South

American Classification Committee

Species

limits in Thamnophilus ruficapillus

Our

current SACC notes read:

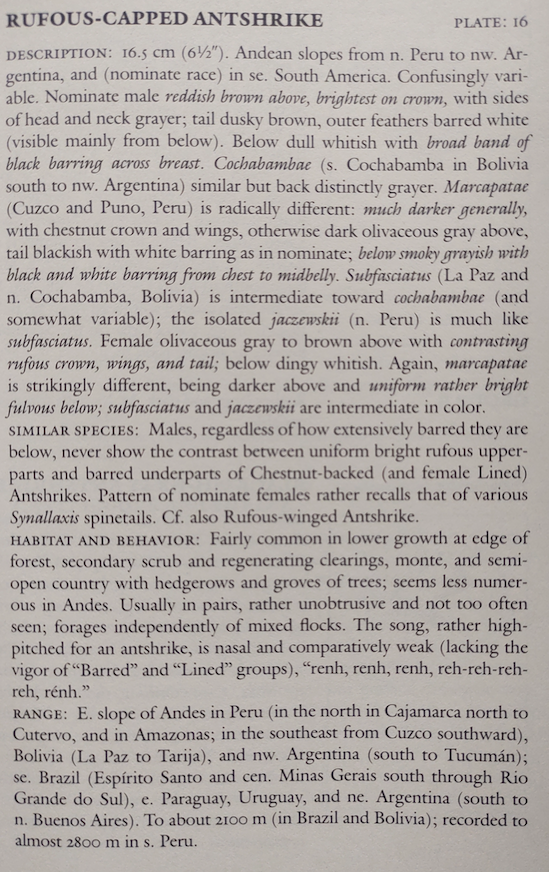

"7c. Short (1975) suggested that

the Andean subspecies (marcapatae and jaczewskii) might warrant

recognition as a separate species from Thamnophilus ruficapillus, but

see Ridgely & Tudor (1994).

7f. Plumage and vocal characters

strongly suggested that Thamnophilus ruficapillus and T. torquatus

should be placed next to the T. doliatus group in linear sequences

(Ridgely and Tudor 1994), and this change in sequence was made by Zimmer &

Isler (2003), who considered them to form a superspecies. Genetic data

(Brumfield & Edwards 2007) strongly support this, with T.

ruficapillus and T. torquatus are sister species and closely related

to T. doliatus. SACC proposal passed to change linear

sequence of species."

The Rufous-capped Antshrike T. ruficapillus is polytypic, with the following 5 subspecies – and

overall distribution:

Atlantic

Forest and Parana/del Plata basin:

• T. r. ruficapillus

Vieillot, 1816 – E Paraguay and SE Brazil (S from E Minas Gerais and Espírito

Santo) S to NE Argentina (Misiones, Corrientes, Entre Ríos, NE Buenos Aires)

and Uruguay.

Andes

(from N to S)

• T. r. jaczewskii

Domaniewski, 1925 – Andes of N Peru (C Cajamarca, Amazonas S of R Marañón, NW

San Martín).

• T. r. marcapatae

Hellmayr, 1912 – E slope of Andes of S Peru (E Cuzco, Puno).

• T. r. subfasciatus

P. L. Sclater & Salvin, 1876 – E slope of Andes of NW Bolivia (La Paz, W

Cochabamba)

• T. r. cochabambae

(Chapman, 1921) – E slope of Andes of C Bolivia (E Cochabamba and SW Santa

Cruz) S to NW Argentina (Jujuy, Salta, Tucumán).

Previous treatments

Short 1975 (pages 262-263) wrote:

"?Thamnophilus ruficapillus

Rufous-capped

Antshrike

Taxonomy. Polytypic. Forms a superspecies with Andean marcapatae (disjunct populations of

latter in northern and in southeastern Peru). Thamnophilus marcapatae is darker, grayer, and less pale rufescent

than ruficapillus, and females are

very dark (rufous) below, not whitish-buff as in ruficapillus.

Ecology. Found in forest undergrowth and in canopy. Nonmigratory.

Distribution and variation. The superspecies is endemic in central

South America. Thamnophilus ruficapillus

occurs from northern Bolivia S along the Andes to Tucumán, and, disjunctly,

from Espirito Santo and eastern Paraguay S to northern Buenos Aires and

Uruguay. It occurs outside of the chaco, but is very likely to reach the

western fringes of the chaco in Salta or western Paraguay, and, in the E, it

possibly may reach the W bank of the Parana River in the Santa Fe chaco. The

eastern nominate ruficapillus is more

rufous and less gray than the western races. Of the two western forms, cochabambae occurs from central Bolivia

S, and is the one likely to occur in the western chaco fringes. It is lighter gray and less fully barred

below than is west-central Bolivian subfasciatus."

Ridgely & Tudor (1994) remarked on

the vocal similarities, highlighted the distinctiveness of marcapatae and suggested that subfasciatus

was intermediate between the northernmost Andean taxa and cochabambae, proposing that variation was clinal:

The BirdLife split:

Del Hoyo & Collar (2016), see also del Hoyo et

al. (2017), split the three north Bolivian/Peruvian taxa (subfasciatus, marcapatae and

jaczewskii) as the

Northern Rufous-capped Antshrike T.

subfasciatus with the following argument:

"Belongs to the “T. doliatus group” (which see). Hitherto

treated as conspecific with T.

ruficapillus, but differs in its denser barring on breast, this extending

to belly and onto throat, in male (3); rufous vs whitish below in female (3);

shorter tail (effect size 2.79, score 2). Three subspecies recognized."

Genetics

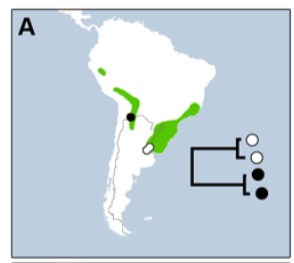

A

series of genetic studies, using different combinations of taxa, are consistent

among them and point to relatively deep divergences among taxa:

• Brumfield & Edwards (2007) found that a sample

of cochabambae and one of torquatus were sister (3.6% divergent in

ND2, 5.2% in Cyt b).

• Kerr et al. (2009) found a deep (ca. 4%)

divergence in COI between cochabambae

and ruficapillus

with two samples per taxon:

More recently, with better geographic sampling but

just one sample per taxon Harvey et al.

(2020) found T.

torquatus as sister to nominate ruficapillus,

whereas cochabambae

was sister to marcapatae

and jaczewskii

(lacking samples of subfasciatus):

![]()

Importantly, note that according to this tree T. ruficapillus would be

paraphyletic whether we follow the traditional arrangement or whether we decide

to split it along BirdLife lines. With all this in mind, one could solve the

lack of monophyly of T. ruficapillus either

by moving cochabambae as a taxon

within subfasciatus or by following a

more drastic course and performing a three-way split, separating cochabambae (monotypic) and subfasciatus (polytypic)

from a monotypic ruficapillus.

However, (a) Harvey et al. (2020) had no genetic samples of nominate subfasciatus, (b) there is

just one sample per taxon, and (c) no rigorous vocal studies have been

conducted.

Vocalizations

The vocalizations of two undisputed species, T. torquatus

and T. ruficapillus, are quite similar. However, no

formal quantitative studies have been published to date for this complex. Mark

and I have recorded cochabambae

and ruficapillus

extensively, in the hope of being able to sit down and analyze the data

properly. Although we still have to do that, our preliminary analyses (Areta

& Pearman, unpublished) indicate that there are some differences, but the

differences are far from obvious: birds in the Andes of NW Argentina (cochabambae) deliver faster paced songs

than lowland birds in NE Argentina (ruficapillus).

This is an interesting study case to apply the Isler et al. (1998) criteria,

that has been instrumental to most taxonomic changes in Thamnophilidae during

the last 25 years.

Plumage

In terms of plumage, the subfasciatus group is the most distinctive, given its extensive and

profuse ventral barring, grey flanks and back, and grey face

(https://macaulaylibrary.org/asset/204867361), whereas cochabambae has a greyish face

(https://macaulaylibrary.org/asset/205684661) that distinguishes it from the

browner-faced, yet very similar ruficapillus

(https://macaulaylibrary.org/asset/68731871). Overall, despite variation, cochabambae has less extensive ventral

barring and is paler dorsally than ruficapillus.

Ridgely & Tudor (1994) (see above) suggested that plumage varied clinally

in Andean taxa.

Brief

analysis

Given the apparent vocal conservatism in the ruficapillus/torquatus clade, we think that a full comparative study is

necessary to correctly sort out the species limits here. More genetic samples

of all taxa (especially including subfasciatus)

would also strengthen the case. Although the plumage differences (the main

features used to describe the taxa) seem well established, a more thorough

characterization of geographic variation would also be welcome, especially to

assess whether variation is clinal across the Andean taxa cochabambae-subfasciatus-marcapatae-jaczewskii. The BirdLife

treatment was based just on plumage and tail length: features that can hardly

be used as solid characters in antbird species-level taxonomy, given the number

of well-studied widespread (biological) species with striking plumage and

morphological differences that exhibit clinal variation.

Voting

options

A) Treat T. ruficapillus as a single, polytypic

species, including the 5 traditional subspecies --- The traditional treatment.

B) Split T. ruficapillus (with ssp. ruficapillus and cochabambae) from T.

subfasciatus (with ssp. subfasciatus,

marcapatae and jaczewskii)

--- The BirdLife treatment.

C) Split T. ruficapillus (monotypic), and T. subfasciatus (with ssp. subfasciatus, marcapatae, jaczewskii and cochabambae)

--- A different 2-species option that achieves monophyly for both: there would

be one Western (Andes) species and one Eastern (Atlantic Forest and Parana/del

Plata river basin) species

D) Split T. ruficapillus (monotypic), T. cochabambae (monotypic) and T. subfasciatus (with

ssp. subfasciatus, marcapatae

and jaczewskii)

--- A 3-species option that has not been suggested before in the literature to

our knowledge.

Recommendation

We recommend a YES to option A and NO to options B, C,

and D. More studies, especially including genetic samples

of nominate subfasciatus and

rigorous, large-scale comparative vocal analyses are needed to sort this

complex out adequately. Collectively, the data indicate that the current

single-species treatment seems erroneous, but we lack enough data to make fully

informed improvements to our classification.

Additional

references

del

Hoyo, J., and N. J. Collar (2016). HBW and BirdLife International Illustrated

Checklist of the Birds of the World. Volume 2. Lynx Edicions, Barcelona, Spain.

del

Hoyo, J., N. Collar, and G. M. Kirwan (2017). Northern

Rufous-capped Antshrike (Thamnophilus subfasciatus). In

Handbook of the Birds of the World Alive (J. del Hoyo, A. Elliott, J. Sargatal,

D. A. Christie, and E. de Juana, Editors). Lynx Edicions, Barcelona. Retrieved

from Handbook of the Birds of the World Alive: https://birdsoftheworld.org/hbw/species/rucant4/1.0

Kerr KCR, Lijtmaer DA,

Barreira AS, Hebert PDN, Tubaro PL. (2009) Probing evolutionary patterns in

Neotropical birds through DNA barcodes. PLoS ONE 4(2): e4379.

doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0004379

Juan I. Areta &

Mark Pearman, February 2023

Comments

from Remsen: “YES to A and NO to B, C, and D, as recommended in the

proposal. I strongly agree with the

theme of the analysis: this is a complex situation that really needs a thorough

study of voice and potential contact zones, with multiple genetic samples from

strategic locations. Making splits based

on differences in tail length and plumage in antbirds is just silly, and using genetic

distance is problematic, for conceptual and practical reasons (that I’ve

elaborated on in many previous proposals; further, the reported distances in

the taxa sampled are routine in Neotropical birds for taxa ranked as subspecies

for lack of vocal differences or evidence of free gene flow in contact zones).”

Comments

from Stiles: “YES

to A- maintain a polytypic T. ruficapillus pending more conclusive data

supporting a split.”

Comments from Del-Rio: “YES to A, and NO to B, C and D. Waiting on an updated phylogenetic

tree to clarify whether ruficapillus would be polyphyletic, for now, keep the status quo.”

Comments

from Zimmer:

“YES to Option A (continue to treat T. ruficapillus as a single,

polytypic species, including the 5 traditionally recognized subspecies.), and

NO to options B, C and D. Although the

incomplete genetic data, and striking differences in both male and female

plumage of some of the Andean taxa versus nominate ruficapillus are

certainly suggestive of more than one species-level taxon being involved, I

agree completely with Nacho and Mark that more genetic, vocal, and

morphological/plumage analyses are needed from throughout the Andean

distribution of taxa to make sense of the variation, and, to rule out clinality

in morphological and vocal characters.

This case actually reminds me a lot of the situation with Thamnophilus

caerulescens, which Mort Isler and I grappled with while working on the

Thamnophilid chapter for Volume 8 of HBW.

As is the case with ruficapillus, caerulescens is a

polytypic species (I think Peters recognized 12 ssp., but Mort and I only

recognized 8.), with a broad, and somewhat unusual distribution that includes a

chain of multiple Andean taxa, as well as Atlantic Forest representatives

ranging from NE Argentina, SE Paraguay, Uruguay, and SE Brazil (and even to NE

Brazil in Ceará and Pernambuco, so even more extensive than the distribution of

ruficapillus). As with ruficapillus-group,

the caerulescens-group encompasses a considerable amount of plumage

variation in both male and female plumages, with males of some subspecies-pairs

and females of others being exceptionally dichromatic. Also, as in the ruficapillus-group,

vocalizations of the caerulescens-group are remarkably consistent across

such a broad range, particularly given the extent of plumage variation within

the group. Our conclusion, when

researching the antbird chapter for HBW, was that, in spite of the apparent

discontinuities in diagnostic plumage characters separating many of the

described subspecies, that it would take a broadly sampled quantitative vocal

analysis to demonstrate any diagnostic vocal characters, and to eliminate the

possibility that perceived distinctions in pace of the loudsongs (which was the

only vocal difference between populations that we could discern from a

qualitative “ear test”) between some populations did not differ clinally. A couple of years later, (2005) the Islers

and Robb Brumfield published just such a study of caerulescens, albeit

one dealing only with the Andean taxa, and not with any of the Atlantic Forest

populations, and found that vocalizations did vary clinally across named

populations. In fact, as I recall, the

only diagnostic vocal character they could find was pace of loudsong (maybe

also number of notes?), and even that single character differed only between

populations at either end of the cline, with no vocal characters allowing

diagnosis of any two adjacent populations.

I thought of this as soon as I read Nacho’s comments in the Proposal

regarding the preliminary results of the vocal study that he and Mark have been

doing on ruficapillus and cochabambae – ‘some differences…far

from obvious…cochabambae delivering faster-paced songs than ruficapillus.’

“All

of this having been said, I still suspect that a similar, thoroughly sampled

genetic, vocal and plumage analysis of the various eastern (NE Brazil south to

Argentina, Paraguay and Uruguay) taxa in the caerulescens-group would

support recognition of at least one species distinct from the Andean

populations. Similarly, I would not be

surprised if such a detailed analysis across all populations of the ruficapillus-complex

would justify some splitting of taxa too, particularly since there is a vocally

similar sister species (T. torquatus) whose range basically fills the

gap between the range of nominate ruficapillus and that of the other

subspecies. But the point is, that it

will take robust analyses such as the molecular and vocal studies of caerulescens

by Brumfield (2007) and Isler et al (2005), not simplified, point-based scoring

systems of plumage or tail length, to resolve the situation in my opinion.”

Comments from LANE: A) YES.

NO to the remaining options. Until it is clear with which group

cochabambae falls, and

what (if any) characters vocal analyses can unearth, I think we should not make

changes that could require reversals once studies are performed. One issue I

think is overlooked in this proposal is the status of T. torquatus with

respect to the rest of T. ruficapillus. In the proposal, they are called

"undisputed species" but I wonder? I will

point out that T.

torquatus and

T. ruficapillus (nominate

group) have extremely limited overlap, and with birds that look like this

(https://macaulaylibrary.org/asset/112680911), (https://macaulaylibrary.org/asset/212242301), (https://macaulaylibrary.org/asset/139135831), (https://macaulaylibrary.org/asset/104308891), (https://macaulaylibrary.org/asset/203030841), (https://macaulaylibrary.org/asset/213202581), (https://www.wikiaves.com.br/2762203&t=s&s=10833&tag=FOTOALIMENTACAO) (https://www.wikiaves.com.br/922533&tm=f&t=s&s=10833&o=mp&o=mp) (https://www.wikiaves.com.br/1313378&tm=f&t=s&s=10833&o=mp&o=mp) (https://www.wikiaves.com.br/1317945&tm=f&t=s&s=10833&o=mp&o=mp) (https://www.wikiaves.com.br/3185750&tm=f&t=s&s=10833&o=mp&o=mp) (https://www.wikiaves.com.br/1761206&tm=f&t=s&s=10833&o=mp&o=mp) (https://www.wikiaves.com.br/2786202&tm=f&t=s&s=10833&o=mp&o=mp) (https://www.wikiaves.com.br/2748024&tm=f&t=s&s=10833&o=mp&o=mp) (https://www.wikiaves.com.br/1744876&tm=f&t=s&s=10833&o=mp&o=mp) (https://www.wikiaves.com.br/2642126&tm=f&t=s&s=10833&o=mp&o=mp) (https://www.wikiaves.com.br/1644632&tm=f&t=s&s=10834&o=mp&o=mp)

at sites where both species

reportedly occur makes me wonder just how “undisputed” the species status of

T. torquatus really is?

Other than the black cap of the male, I don’t see or hear a whole lot that

distinguish the two… and is that black cap as important a feature in the birds’

eyes as it seems to be for us? My point is: I am not entirely convinced that we

should be leaving T.

torquatus out of this complex simply

because it looks so distinctive to human eyes. It may be best inserted into

T. ruficapillus,

and then the paraphyly of the latter is no longer! According to

Wagner Nogueira, it seems

that the present-day contact of the two taxa is thanks to recent anthropogenic

habitat alteration, so a broad region of contact and overlap is not to be

expected, and the above evidence of potential interbreeding could be a

precursor of a larger future swarm.”

Comments from Rafael Lima: “I

agree with Daniel that it may be best to lump T. torquatus with the

T. ruficapillus complex, at least

provisionally while thorough genetic and acoustic trait analyses are not

available. Although this possibility has not been considered in the

original proposal, it would equally eliminate paraphyly.

“I have recently cursorily

examined dozens of specimens of almost all taxa of the complex at the

AMNH, LSUMNS, and MZUSP, and my impression is that if two biological species

were to be recognized in this complex for the time being, based on morphology

alone, these species should be the eastern taxa (ruficapillus + torquatus)

comprising one species and the Andean taxa (subfasciatus + marcapatae

+ jaczewskii + cochabambae) comprising the other species.

Subspecies cochabambae is difficult to place in one of the two

morphologically-delimited species, but I think this arrangement makes much more

sense than treating the Andean taxa plus ruficapillus as one species and

torquatus as another. This arrangement would also result in two monophyletic

species taxa. Nevertheless, I think that based on current evidence (including

the many photos on WikiAves suggesting that torquatus and ruficapillus

hybridize freely where they come into contact), the best option is to treat all

of them as a single biological species until a thorough study of geographic

variation is available.”

Comments from Robbins: “YES to A, no to B, C, D for

reasons outlined in the proposal and based on comments by other committee

members.”

Comments from Claramunt: “Option A. The situation is

clearly complex and requires a detailed analysis of the evidence. Nothing new

has been published. NO to B,C,D.”

Comments from Bonaccorso: “A, YES. No to B, C, D. The

problem with the last three proposals is not only the lack of vocal data (as

the proposal indicates), but there is also a lack of good geographic and

genetic sampling across the ranges of all taxa involved in the potential alternatives.”