Proposal (970) to South

American Classification Committee

Note from Remsen: This proposal is being evaluated by NACC concurrently

Revise

generic limits among Rhodothraupis, Periporphyrus, and Caryothraustes,

and adopt a new linear sequence for these taxa

Background:

Rhodothraupis celaeno (Deppe, 1830) is a

dichromatic understory cardinalid of the lowlands of northeastern Mexico, the

males being largely dark red with a solid black head and dark back, whereas the

females have the red replaced by yellowish olive (Brewer 2020b). This overall

plumage pattern is shared by Periporphyrus erythromelas ("Gmelin,

JF", 1789) of northeastern South America and the southeastern Amazon

Basin, although that species is brighter red (males) or yellow (females),

especially on the back, and has a larger bill (Brewer 2020a, eBird records).

After being placed in various ‘catchall’ genera (e.g., Loxia, Fringilla)

in the 19th century, Rhodothraupis celaeno bounced around

between the monotypic genus Rhodothraupis Ridgway 1898, Periporphyrus

Reichenbach 1850, Caryothraustes Reichenbach 1850, and Pitylus

Cuvier 1829 (Ridgway 1901, Hellmayr 1938), whereas Periporphyrus

erythromelas moved between its current genus and Pitylus Cuvier 1829

(Hellmayr 1938). Molecular data have now shown Pitylus to be part of Saltator

in the Thraupidae, but the remaining three genera are closely related and part

of the Cardinalidae (Barker et al. 2015). Parkerthraustes humeralis

(Lawrence 1867) was previously considered a Caryothraustes until

molecular data showed it belonged in the Thraupidae (Demastes and Remsen 1994).

In the current treatment of NACC/SACC, Caryothraustes contains two

species: poliogaster of Mexico and Central America and canadensis

of northeastern South America, southeastern Brazil, and eastern Panama

(Clements et al. 2022). Both species of Caryothraustes are

monochromatic, largely arboreal lowland species. Both Rhodothraupis celaeno

and Periporphyrus erythromelas are mostly understory / midstory species,

and at least Periporphyrus will join mixed flocks (Brewer 2020a).

All four species in this group give

leisurely whistled songs in short but widely separated strophes (i.e., typical

cardinalid songs), although the pattern differs between species. The two Caryothraustes

also give a variety of “loud and arresting” calls when flocking, described as a

“zzzrt”, “tree-dreek”, or “chew-chew-chew” (Gulson 2020). Rhodothraupis and

Periporphyrus both give more subtle calls; a “high, clear, penetrating

slurred ‘sseeuu’” in Rhodothraupis and a ”high-pitched, sharp ‘spink’”

in Periporphyrus (Brewer 2020a, 2020b).

The last major generic revision of this

group was that of Ridgway (1901), resulting in the treatment followed by most

subsequent authors, with Rhodothraupis and Periporphyrus each

being monotypic, and Caryothraustes with two species (e.g. Dickinson and

Christidis 2014, Gill et al. 2020, Clements et al. 2022, Chesser et al. 2023).

Paynter (1970) lumped Caryothraustes poliogaster with canadensis,

but that treatment was not followed by subsequent authors. SACC recently

considered a proposal to split Caryothraustes canadensis, which

did not pass. In addition to whether the species were dichromatic or

monochromatic, Ridgway (1901) used the following structural characters to

delimit genera: Periporphyrus with a culmen longer than the tarsus,

concave mandibular tomium, and a “broad truncated prominence” at the base of

the tomium (i.e. a “toothed” tomium), Rhodothraupis with a relatively

longer tail and narrower bill, and Caryothraustes with a relatively

shorter tail and broader bill. We now know that bill shape is extremely labile

in the Cardinalidae, with a particularly drastic example being “Guiraca”

[=Passerina] caerulea.

del Hoyo et al. (2016) transferred both Rhodothraupis

and Periporphyrus to Caryothraustes but provided no rationale

for this action. Both Periporphyrus and Caryothraustes were

described in the same volume by Reichenbach (Reichenbach 1850), but I am unable

to locate a copy of this volume to review the genus descriptions. Hellmayr

(1938) lists the two genera as being described on sequential plates 77 (Periporphyrus)

and 78 (Caryothraustes). My interpretation is that these genera were

therefore simultaneously published, and that in transferring Periporphyrus

to Caryothraustes, del Hoyo et al. (2016) should be considered the First

Revisers when they selected Caryothraustes as having priority.

New Information:

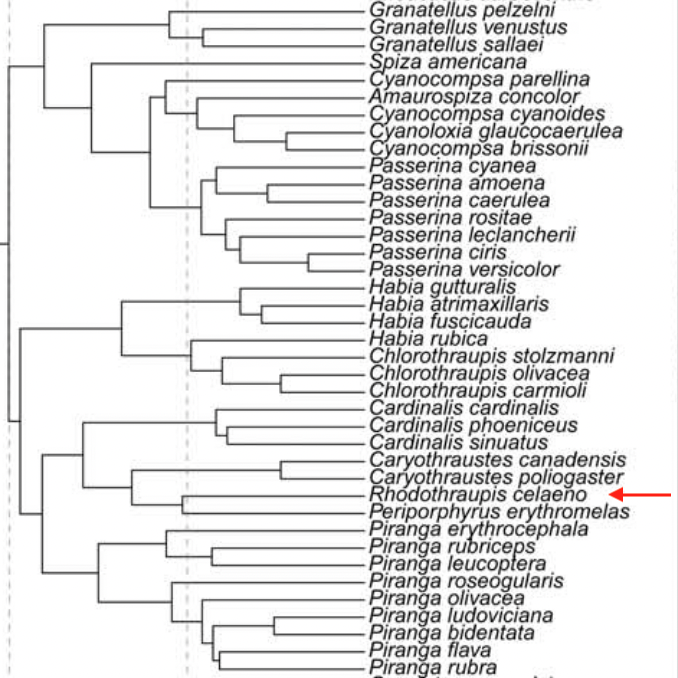

Barker et al. (2015) used a supertree

approach to estimate a phylogeny for the 9-primaried oscines which resulted in

many genus and family level rearrangements that have since been adopted by

NACC, SACC, and other authorities. This tree was based primarily on the

mitochondrial genes Cyt-B and ND2, augmented by four nuclear genes for

representatives of most genera. Below I have reproduced a portion of the tree

showing most of the Cardinalidae, including the species relevant to this

proposal (Figure 1). Of note is that Rhodothraupis, Periporphyrus,

and Caryothraustes form a clade sister to Cardinalis. Rhodothraupis

and Periporphyrus are sister taxa, separated by about 5 Ma (right-most

dashed line in Figure 1). A more recent phylogenetic analysis of Caryothraustes

(Tonetti et al. 2017; with Rhodothraupis and Periporphyrus as

outgroups) using the mitochondrial locus ND2 found similar branch lengths and

topology as Barker et al. (2015).

Figure 1. A portion of

the Cardinalidae phylogeny from Barker et al. (2015). The two vertical dashed

lines correspond to 10 Ma (left-hand line) and 5 Ma (right-hand line). Rhodothraupis

celaeno is indicated with a red arrow.

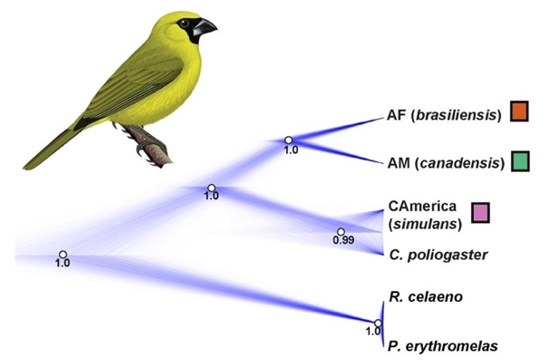

A more recent study on sister

relationships of multiple complexes of Amazonian and Atlantic Forest taxa

(Bocalini et al. 2021) included all subspecies of Caryothraustes and

both Rhodothraupis and Periporphyrus as outgroups. They estimated

a coalescent-based species tree from 3,826 UCE SNPs, which I have reproduced

below (Figure 2). As an aside, Bocalini et al. (2021) found that Caryothraustes

canadensis simulans of eastern Panama was sister to C. poliogaster,

rather than to the remainder of C. canadensis, so a species-level

taxonomic change should be considered for simulans, either considering

it a separate species or transferring it to C. poliogaster.

Figure 2. The phylogeny

of Caryothraustes and two outgroups, estimated in SNAPP. From Bocalini

et al. (2021).

The topology of the phylogenies in

Barker et al. (2015) and Bocalini et al. (2021) are concordant, but the branch

lengths are extremely different. Most notably, the UCE tree in Bocalini et al.

(2021) found extremely low divergence between Rhodothraupis and Periporphyrus

(far less than the divergence within Caryothraustes),

although I note that this is a coalescent-based analysis, which in my

experience often recovers lower divergence estimates than maximum likelihood

methods like those used in Barker et al. (2015). The Barker et al. (2015) study

was based on many fewer loci, which may also explain the different branch

lengths between the two studies.

A series of specimens of the relevant

species in this group are shown on below, courtesy of Terry Chesser. Within

each species, males are on the left and females on the right, and the species

from left to right are: Rhodothraupis celaeno, Periporphyrus

erythromelas, Caryothraustes poliogaster, and Caryothraustes canadensis.

Effect on AOS-CLC area:

Merging Rhodothraupis into Periporphyrus

would result in a name change from Rhodothraupis celaeno to Periporphyrus

celaeno. Merging all species into Caryothraustes (following del Hoyo

et al. 2016) would result in name changes for Rhodothraupis celaeno and Periporphyrus

erythromelas in the following linear sequence: Caryothraustes celaeno,

C. erythromelas, C. poliogaster, C. canadensis.

Recommendation:

The two major clades in this group have

the same number of species (2), and Rhodothraupis celaeno is the

northern-most member of the group, so regardless of any genus-level transfers celaeno

should go first in the linear sequence. I recommend adopting a new linear

sequence (see below), which differs only slightly from the current NACC

treatment.

The ~5 Ma divergence between Rhodothraupis

and Periporphyrus in Barker et al. (2015) is less than that shown by

most related cardinalid genera, and the very low divergence between the

two species found by Bocalini et al. (2021) suggests that these two species are

very closely related. The bill size / shape differences are best not considered

genus-level characters in the Cardinalidae, and I find the wing and tail length

differences to not be drastically different. Combined with the broadly similar

red-and-black (male) and green-and-black (female) plumages of Rhodothraupis and

Periporphyrus, I think Rhodothraupis celaeno is best transferred

to Periporphyrus.

Based solely on relative branch lengths

in Barker et al. (2015), the divergence between Caryothraustes and Rhodothraupis

+ Periporphyrus is roughly comparable to some other genus-level

divergences in the Cardinalidae, such as those among Amaurospiza,

Cyanoloxia, and Cyanocompsa. These similar genus-level clade ages,

combined with the differing plumage dimorphism (monochromatic in Caryothraustes

vs. dichromatic in Rhodothraupis and Periporphyrus), and a

more canopy-dwelling habit and differing calls of Caryothraustes, are

sufficient in my view to keep Caryothraustes and Periporphyrus as

separate genera. Although I minimized the importance of the bill shape

differences in advocating for the merger of Rhodothraupis and Periporphyrus,

the two Caryothraustes do have a notably wide bill. Caryothraustes

do also look superficially like females of Rhodothraupis and Periporphyrus,

albeit with restricted black on the head. That said, I don’t think that a

merger of Caryothraustes and Periporphyrus is necessary, although

it would maintain a monophyletic grouping.

Please vote on the following:

A. Adopt the following linear sequence: celaeno (extralimital),

erythromelas, poliogaster (extralimital), canadensis.

B. Transfer Rhodothraupis celaeno (extralimital) to

Periporphyrus (advisory only)

C. Transfer Rhodothraupis celaeno and Periporphyrus

erythromelas to Caryothraustes (only if B passes)

I recommend a YES on A and B, and

a NO on C.

Literature Cited:

Barker, F.

K., Burns, K. J., Klicka, J., Lanyon, S. M., and Lovette, I. J. 2015. New

insights into New World biogeography: An integrated view from the phylogeny of

blackbirds, cardinals, sparrows, tanagers, warblers, and allies. The Auk,

132(2), 333–348. https://doi.org/10.1642/AUK-14-110.1

Bocalini,

F., Bolívar-Leguizamón, S. D., Silveira, L. F., and Bravo, G. A. 2021.

Comparative phylogeographic and demographic analyses reveal a congruent pattern

of sister relationships between bird populations of the northern and

south-central Atlantic Forest. Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution, 154,

106973. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ympev.2020.106973

Brewer, D.

2020a. Red-and-black Grosbeak (Periporphyrus erythromelas), version 1.0.

In Birds of the World (J. del Hoyo, A. Elliott, J. Sargatal, D. A. Christie,

and E. de Juana, Editors). Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, NY, USA. https://doi.org/10.2173/bow.rabgro1.01

Brewer, D.

2020b. Crimson-collared Grosbeak (Rhodothraupis celaeno), version 1.0.

In Birds of the World (J. del Hoyo, A. Elliott, J. Sargatal, D. A. Christie,

and E. de Juana, Editors). Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, NY, USA. https://doi.org/10.2173/bow.crcgro.01

Chesser,

R. T., S. M. Billerman, K. J. Burns, C. Cicero, J. L. Dunn, A. W. Kratter, I.

J. Lovette, N. A. Mason, P. C. Rasmussen, J. V. Remsen, Jr., D. F. Stotz, and

K. Winker. 2023. Check-list of North American Birds (online). American

Ornithological Society.

Clements,

J. F., T. S. Schulenberg, M. J. Iliff, T. A. Fredericks, J. A. Gerbracht, D.

Lepage, S. M. Billerman, B. L. Sullivan, and C. L. Wood. 2022. The

eBird/Clements checklist of Birds of the World: v2022. Downloaded from https://www.birds.cornell.edu/clementschecklist/download/

Demastes,

J. W., and J. V. Remsen, Jr. 1994. The genus Caryothraustes

(Cardinalinae) is not monophyletic. Wilson Bulletin 106(4): 738–743.

Dickinson,

E. C., and L. Christidis (Editors) (2014). The Howard and Moore Complete

Checklist of the Birds of the World. 4th edition. Volume Two.

Passerines. Aves Press Ltd., Eastbourne. UK.

Gill, F.,

D. Donsker, and P. C. Rasmussen (Editors) (2020). IOC World Bird List (v 10.2).

DOI 10.14344/IOC.ML.10.2. http://www.worldbirdnames.org/

Gulson, E.

R. 2020. Black-faced Grosbeak (Caryothraustes poliogaster), version 1.0.

In Birds of the World (T. S. Schulenberg, Editor). Cornell Lab of Ornithology,

Ithaca, NY, USA. https://doi.org/10.2173/bow.blfgro1.01

Hellmayr,

C. E. 1938. Catalogue of birds of the Americas, part XI. Field Museum of

Natural History Zoological Series Vol. XIII. Chicago, USA.

del Hoyo,

J., Collar, N.J., Christie, D.A., Elliott, A., Fishpool, L.D.C., Boesman, P.

and Kirwan, G.M. 2016. HBW and BirdLife International Illustrated Checklist of

the Birds of the World. Volume 2: Passerines. Lynx Edicions and BirdLife

International, Barcelona, Spain and Cambridge, UK.

Paynter,

R. A., JR. 1970. Subfamily Cardinalinae. Pp. 216-245 in Check-list of birds of

the world (R. A. Paynter, Jr., ed.). Museum of Comparative Zoology, Cambridge,

Massachusetts

Reichenbach,

H. G. L. 1850. Avium systema naturale. Das natürliche System der Vögel.

Expedition der vollständigsten naturgeschichte. Dresden and Leipzig.

Ridgway,

R. 1901. The birds of North and Middle America. Part I. Bulletin of the United

States National Museum. No. 50.

Tonetti,

V. R., F. Bocalini, L. F. Silveira, and G. Del-Rio. 2017. Taxonomy and

molecular systematics of the Yellow-green Grosbeak Caryothraustes canadensis

(Passeriformes: Cardinalidae). Revista Brasileira de Ornitologia 25: 176–189.

Oscar Johnson,

February 2023

Vote tabulation:

https://www.museum.lsu.edu/~Remsen/SACCPropChart864+.htm

Comments

from Robbins: “YES. I support the new linear sequence proposed by Oscar and

also vote Yes for the rationale he presents in placing Rhodothraupis celaeno

in Periporphyrus. I would support

either maintaining Periporphyrus or placing it within Caryothraustes.”

Comments

from Stiles: “YES

to all recommendations. A- the new sequence based on geography fits with the

closer affinities between Periporphyrus and Rhodothraupis than with Caryothraustes; B- genetic,

plumage and ecological similarities lend support to merging Rhodothraupis

into Periporphyrus, and C- vocal, genetic and ecological differences

support maintaining separate Periporphyrus from Caryothraustes.”

Comments from Areta:

“A-YES to the proposed linear sequence.

“B-NO. I don´t see a pressing need to move

Rhodothraupis into

Periporphyrus. My main arguments have to deal with

side-effects that I think should be considered with a broader comparative

framework in mind. This seems a borderline case to me in which any option can

be defended, but merging them should (from my perspective)

lead to a cascade effect also

requiring decisions on what to do with other genera, given the lack of

monophyly of Habia, and the

deep divergences in Piranga. I think

that it would be more appropriate to deal with the

Rhodothraupis/Periporphyrus

case after a comparative study is published dealing with generic

limits in this clade. I find it difficult to decide what to do with the long

branch length of Rhodothraupis/Periporphyrus,

without further context on generic limits in the group. For

example, H. rubica

seems to have diverged from

Chlorothraupis at about

the same time as Rhodothraupis

and Periporphyrus, and two

even more deeply diverged clades have been uncovered in Piranga. I feel

that we need a better comparative internal yardstick in order to decide. Otherwise,

this merger might (or might not) need to be undone soon. I am not strongly

opposed to merging Rhodothraupis

into Periporphyrus, it is

just that I do not know how other pieces in the puzzle will fit and I prefer to

have the advantage of a broader comparative look before deciding to change this

well-entrenched taxonomy.

“C-NO. Pretty much for the same reasons that I voted NO to B: one

could choose to accommodate the generic limits in different ways depending on

different criteria, but I do not think it is advisable to mess around with

Rhodothraupis/Periporphyrus/Caryothraustes

without a clear perspective on what to do with other close

relatives. For example, one could follow the merger of

Rhodothraupis and

Periporphyrus into

Caryothraustes and then

also decide to merge Habia with

Chlorothraupis and

recognizing a deeply diverged Piranga. I would

possibly vote against all these three if the moment arrives, but this would be

another way of dealing with generic limits in this clade. An integrative

perspective on genetic and phenotypic variation in this clade should give us

more elements to make a balanced decision towards establishing generic limits.”

Comments from Lane: “A) YES.

B) NO, I don’t see a need to do this, given the long branches involved and the

distinctions between the two species. C) NO, as per B, this seems an

unnecessary move given the distinctiveness of the taxa involved.”

Comments from Claramunt: “I broadly concur with

Oscar’s assessment and recommendation:

“A – YES

“B – YES. erythromelas

and celaeno are two sister species with similar morphologies, plumage,

and ecology. Treating them in the same genus makes total sense. The genus

category is most useful when it groups multiple species indicating

relationships and monophyletic groups. Monotypic genera fail at that. I know

that monotypic genera are sometimes unavoidable, but this is a case in which

they are avoidable, and a single genus with two species in it makes a lot of

sense.

“C – NO. If

it were only for their plumage, I would merge all fours species into a single

genus, but I think it makes more sense to maintain the big and red erythromelas

and celaeno separated from the smaller, yellow, and canopy-dwelling Caryothraustes.”

Comments from Remsen:

“A. YES. Required book-keeping.

“B. YES.

The genetic differences are minor, and the differences in plumage insufficient

on their own to assign them to different genera.

“C. NO. The estimated

divergence time is early Miocene, well within the range of lineage ages of most

groups considered to be in separate genera, so I see no objective reason to

upset the status quo

Comments

from Zimmer:

“A) YES on adopting the

proposed linear sequence of celaeno, erythromelas (NOTE that it

is celaeno that is extralimital, not erythromelas as stated in

the Proposal), poliogaster, canadensis.

“B) YES on transferring

Rhodothraupis celaeno to Periporphyrus, as supported by multiple

data sets.

“C) NO, on folding Rhodothraupis

celaeno and Periporphyrus erythromelas into Caryothraustes. In addition to all of the differences between

these two species-pairs cited by Oscar, I would add that both Caryothraustes

troop through the forest in noisy groups of up to 20 (or more) individuals –

very unlike celaeno or erythromelas, which, at least in my

experience, tend to be encountered as rather retiring, inconspicuous pairs or

individuals.”

Comments

from Bonaccorso:

“YES on A. The phylogenies are concordant. I wouldn't

worry too much about the differences in branch lengths since we are basically

comparing a mitochondrial-DNA-driven tree with a coalescent-based tree. Based

on plumage dichromatism, and overall size and bill size, transferring Rhodothraupis

celaeno to Periporphyrus seems

reasonable, so YES to B. No to C.”

Comments from Gustavo Bravo (who has Del-Rio vote): “Given

the evidence from various datasets, I support keeping the two larger-sized and

sexually dichromatic (red/yellow) species in one genus and the smaller and

sexually monochromatic in another. Species limits within Caryothraustes

will have to be revisited in the future. Thus, my vote goes as follows:

A – YES.

B – YES.

C– NO.”

Comments

from Stiles:

“YES to A + B, NO on C. I especially dislike lumping all of these in Caryothraustes,

which differs in plumage, vocalizations and habits from Periporphyrus.