Proposal (984) to South

American Classification Committee

Note from Remsen: This is a modification for

SACC of a proposal Oscar has submitted to NACC

Treat Piaya

mexicana and P. “circe” as

separate species from P. cayana (Squirrel Cuckoo)

Description of the

problem:

A recent NACC proposal (2022-B-11;

https://americanornithology.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/03/2022-B.pdf) to split

Piaya mexicana from P. cayana failed unanimously, largely due to

a lack of genetic or vocal data, or information from the contact zone of mexicana

and thermophila. A recent paper (Sánchez‐González et al. 2023)

addressed some of these issues, and proposal 2022-B-11 overlooked genetic data

published in Smith et al. (2014). This proposal incorporates that genetic

information and additional taxonomic information from Colombia and Venezuela that

is relevant to the potential split of South American taxa. We encourage

committee members to read proposal 2022-B-11and comments on that proposal

(https://americanornithology.org/about/committees/nacc/current-prior-proposals/2022-proposals/comments-2022-b/#2022-B-11).

In particular, proposal 2022-B-11 contains photos of specimens that are

relevant to the current proposal. The introduction to this proposal includes

much of the same text as in 2022-B-11 but expands on certain topics overlooked

in 2022-B-11. Similar proposals to split Piaya cayana are being

considered concurrently by both NACC and WGAC.

![]() Piaya cayana (Linnaeus 1766) is a widespread

polytypic species found from northern Mexico to Argentina, with as many as 14

subspecies recognized (Fitzgerald et al. 2020). The species is common in

forested lowlands and foothills throughout its range. Details on relevant

subspecies are outlined here. In Middle America, the darker subspecies thermophila Sclater, 1859, is found from

eastern Mexico south to northwestern Colombia but is replaced on the Pacific

coast of the Isthmus of Tehuantepec by the pale west Mexican subspecies mexicana (Swainson, 1827), which

is found in dry forests from the Isthmus of Tehuantepec north to Sonora and

Chihuahua. Fitzgerald et al. (2020) treated thermophila as a monotypic

subspecies group, with a distribution extending south to northwestern Colombia,

where it is replaced by another monotypic subspecies group, nigricrissa

(Cabanis, 1862) of the Chocó from northwestern Colombia south to northern

Ecuador on the Pacific slope, although nigricrissa reaches as far east

as the eastern slope of the central Andes in Colombia (Chapman 1917). As the

name suggests, nigricrissa has a darker blackish vent compared to thermophila,

but it is otherwise similar. Fitzgerald et al. (2020) considered all remaining

subspecies to be part of the cayana group. In northern Colombia, thermophila

is replaced to the east by the pale rufous mehleri

Bonaparte, 1850, in the dry forests of northern Colombia and Venezuela, and

south into the Magdalena Valley of Colombia. The even paler rufous circe Bonaparte, 1850, replaces mehleri south of Lago Maracaibo. Either circe or mehleri

is found east to the Río Orinoco delta, and insulana

Hellmayr, 1906, is found on Trinidad. Subspecies mesura

(Cabanis and Heine, 1863) replaces these pale rufous taxa south across the Río

Orinoco in the northwestern Amazon Basin, likely meeting mehleri

and nigricrissa via low passes in the Andes (Chapman 1917). Compared

to nigricrissa, mesura is paler below

and has a red rather than greenish-yellow orbital skin (Ridgely and Greenfield

2001). The nominate cayana is found in the humid Guiana Shield.

Additional subspecies are found south through the remainder of South America.

Piaya cayana (Linnaeus 1766) is a widespread

polytypic species found from northern Mexico to Argentina, with as many as 14

subspecies recognized (Fitzgerald et al. 2020). The species is common in

forested lowlands and foothills throughout its range. Details on relevant

subspecies are outlined here. In Middle America, the darker subspecies thermophila Sclater, 1859, is found from

eastern Mexico south to northwestern Colombia but is replaced on the Pacific

coast of the Isthmus of Tehuantepec by the pale west Mexican subspecies mexicana (Swainson, 1827), which

is found in dry forests from the Isthmus of Tehuantepec north to Sonora and

Chihuahua. Fitzgerald et al. (2020) treated thermophila as a monotypic

subspecies group, with a distribution extending south to northwestern Colombia,

where it is replaced by another monotypic subspecies group, nigricrissa

(Cabanis, 1862) of the Chocó from northwestern Colombia south to northern

Ecuador on the Pacific slope, although nigricrissa reaches as far east

as the eastern slope of the central Andes in Colombia (Chapman 1917). As the

name suggests, nigricrissa has a darker blackish vent compared to thermophila,

but it is otherwise similar. Fitzgerald et al. (2020) considered all remaining

subspecies to be part of the cayana group. In northern Colombia, thermophila

is replaced to the east by the pale rufous mehleri

Bonaparte, 1850, in the dry forests of northern Colombia and Venezuela, and

south into the Magdalena Valley of Colombia. The even paler rufous circe Bonaparte, 1850, replaces mehleri south of Lago Maracaibo. Either circe or mehleri

is found east to the Río Orinoco delta, and insulana

Hellmayr, 1906, is found on Trinidad. Subspecies mesura

(Cabanis and Heine, 1863) replaces these pale rufous taxa south across the Río

Orinoco in the northwestern Amazon Basin, likely meeting mehleri

and nigricrissa via low passes in the Andes (Chapman 1917). Compared

to nigricrissa, mesura is paler below

and has a red rather than greenish-yellow orbital skin (Ridgely and Greenfield

2001). The nominate cayana is found in the humid Guiana Shield.

Additional subspecies are found south through the remainder of South America.

HBW-BirdLife

split mexicana from the remainder of Piaya cayana based on plumage and slight

vocal differences and parapatric distribution; citations are Navarro-Sigüenza

and Peterson (2004) and Howell (2013, in litt.): "[mexicana] differs

from parapatric subspecies thermophila

of P. cayana in its rufous underside

of tail feathers with broad black subterminal bar and broad white terminal tip

vs all-black underside of tail with broad white terminal tip (3); pale grey vs

smoky-grey lower belly and vent (2); much brighter rufous upperparts and paler

throat (1); usually greenish-grey vs greenish-yellow orbital ring (Howell 2013)

(ns1); longer tail (effect size 2.01; score 2); “somewhat different” song

(Howell 2013) (allow 1); and parapatric distribution (3)."

Piaya mexicana was described as a

species by Swainson (1827), who gave the following characters (which largely

mirror the differences described above): “Closely resembles C. cayenensis L. [=Piaya

cayana], but the tail beneath is rufous, not black; the ferruginous colour of the head and neck is likewise much brighter.”

This treatment was maintained by authors through the beginning of the 20th

century (Ridgway 1916, Cory 1919), until mexicana was lumped with P. cayana by Peters (1940). Ridgway

expanded on the differences between mexicana:

“Resembling P. cayana thermophila,

but colored portion of under surface of rectrices cinnamon-rufous (instead of

brownish black) with a dull black area immediately preceding the white tip,

general coloration much lighter, and tail relatively much longer.” Most authors

since Peters (1940) have maintained mexicana

as a subspecies of cayana.

Navarro-Sigüenza

and Peterson (2004) used Piaya cayana

as one of their case studies for contrasting a BSC classification (single

species) with a PSC/ESC classification (two species) by splitting mexicana, using this rationale:

“Populations along the Pacific lowlands from Sonora to the Isthmus of

Tehuantepec are long-tailed, pale in coloration of the underparts, whereas the

forms of eastern Mexico and Central America are shorter-tailed and darker in

color. Although a narrow contact zone is present in eastern Oaxaca between the

two forms, only one “hybrid” specimen is known and the

differences are maintained even in close parapatry.” The reference to the

“narrow” contact zone appears to be from Binford (1989), who reported a few

specimens intermediate between thermophila

and mexicana: “I have seen definite

intermediates from Rio Ostuta (MLZ 45402), Las Tejas (MLZ 54387), and Tehuantepec City (UMMZ 137345 and

137350), but some specimens from the last two localities are mexicana. Birds from Tapanatepec,

Santa Efigenia, and a point 18 mi south of Matias

Romero are close to thermophila but

very slightly paler, a condition that might represent response to the drier

environment rather than intergradation” but noted that the "abruptness and

apparent rarity of intergradation suggest that these two forms might be

separate species; a detailed study is needed.” This, combined with the

unpublished information from Howell (2013) mentioned above, appears to

constitute the basis for the HBW-BirdLife split of mexicana from the remainder of P.

cayana. NACC proposal 2022-B-11

also contains photos of two potential intermediate specimens from this region.

Ridgway

(1916) considered mexicana a species distinct from cayana, noting

that “these certainly represent two specific types; certainly it is impossible

that P. c. thermophila and P. mexicana can be conspecific, for

perfectly typical examples of each occur together in the State of Oaxaca, and

none of the large number of specimens examined shows the slightest

intergradation of characters.” In the list of specimens examined for both thermophila

and mexicana is the locality “Oaxaca; Tehuántepec”, which is where we

now know there is a limited contact zone. However, his note that there isn’t

the “slightest intergradation” does suggest that there is likely limited or no

intergradation of characters outside of this contact zone.

New information:

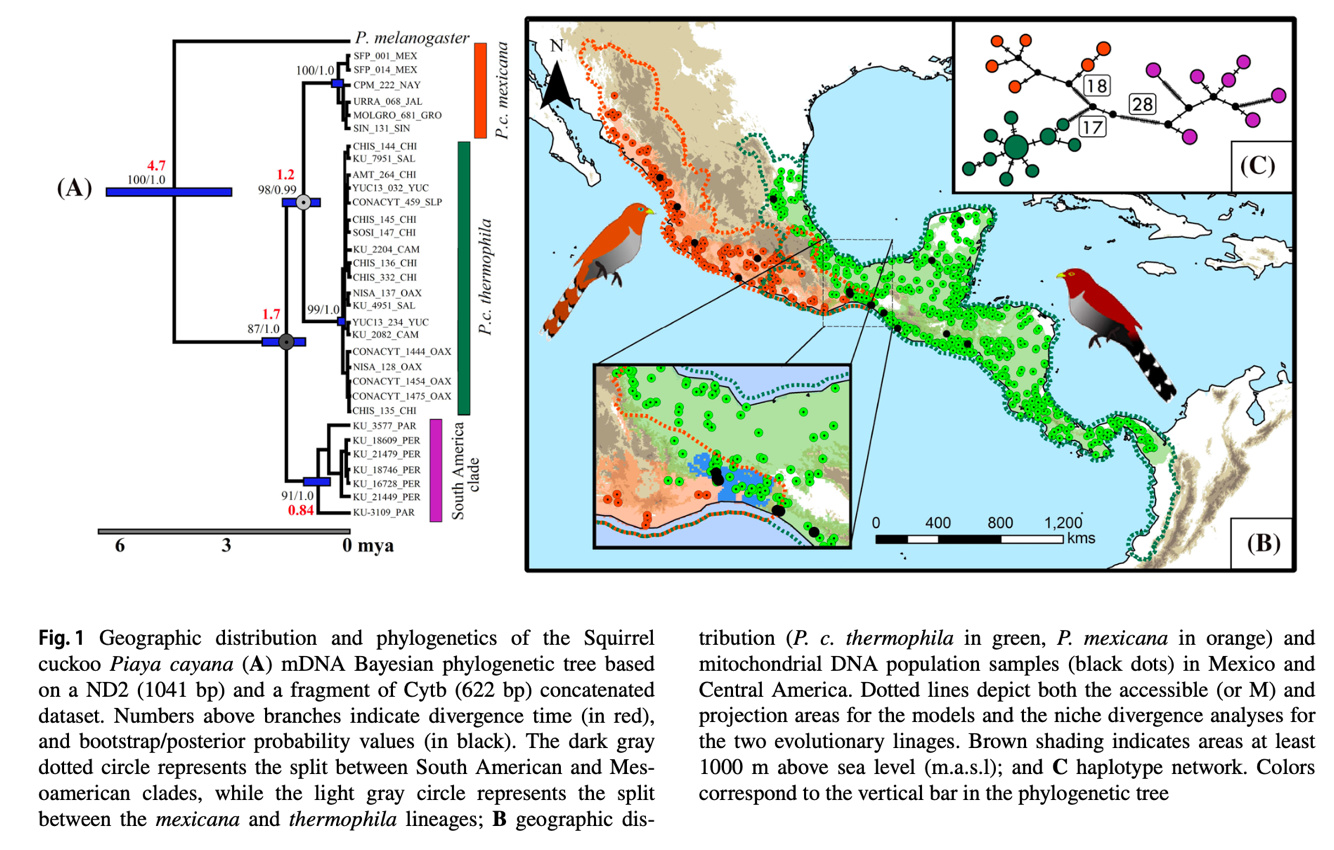

Sánchez‐González et al. (2023) and Smith et al.

(2014) each analyzed 1-2 mitochondrial markers from across the range of Piaya

cayana. Sánchez‐González et al.

(2023) recovered mexicana and thermophila as sister taxa, with a

divergence time of

1.24 mya (1.8 – 0.8 mya, 95% HPD), with nigricrissa unsampled. The mexicana + thermophila

clade was in turn sister to seven samples from Peru and Paraguay with a divergence time listed in the main

text of about 4.7 mya (6.5–3.2

mya, 95% HPD). However, this latter divergence time estimate appears to be an

error, based on the values shown in Figure 1. The 4.7 mya divergence date in

the figure is that of P. cayana vs. P. melanogaster, whereas the

divergence time of the Amazonian vs. the mexicana + thermophila clade

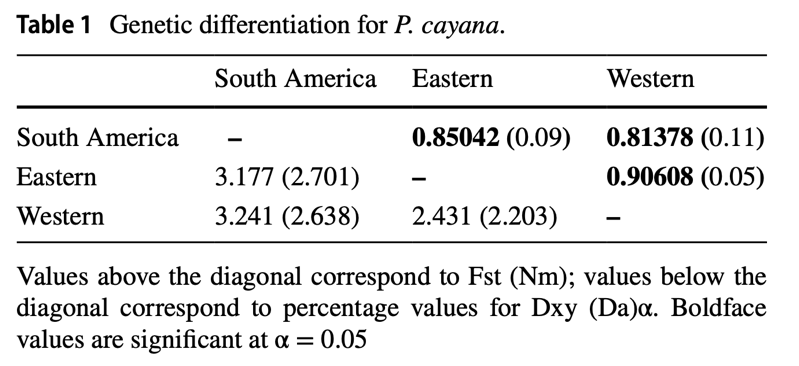

is 1.7 mya. FST and Dxy

divergence values are shown in their Table 1, and their phylogenetic tree,

haplotype network, and sampling map are shown in their Figure 1, below. The FST

results in Table 1 show FST with Nm (the number of migrants per

generation) in parentheses. However, estimates of Nm based on FST

are notoriously unreliable, especially from so few loci. See Whitlock and

McCauley (1999) for discussion of this issue.

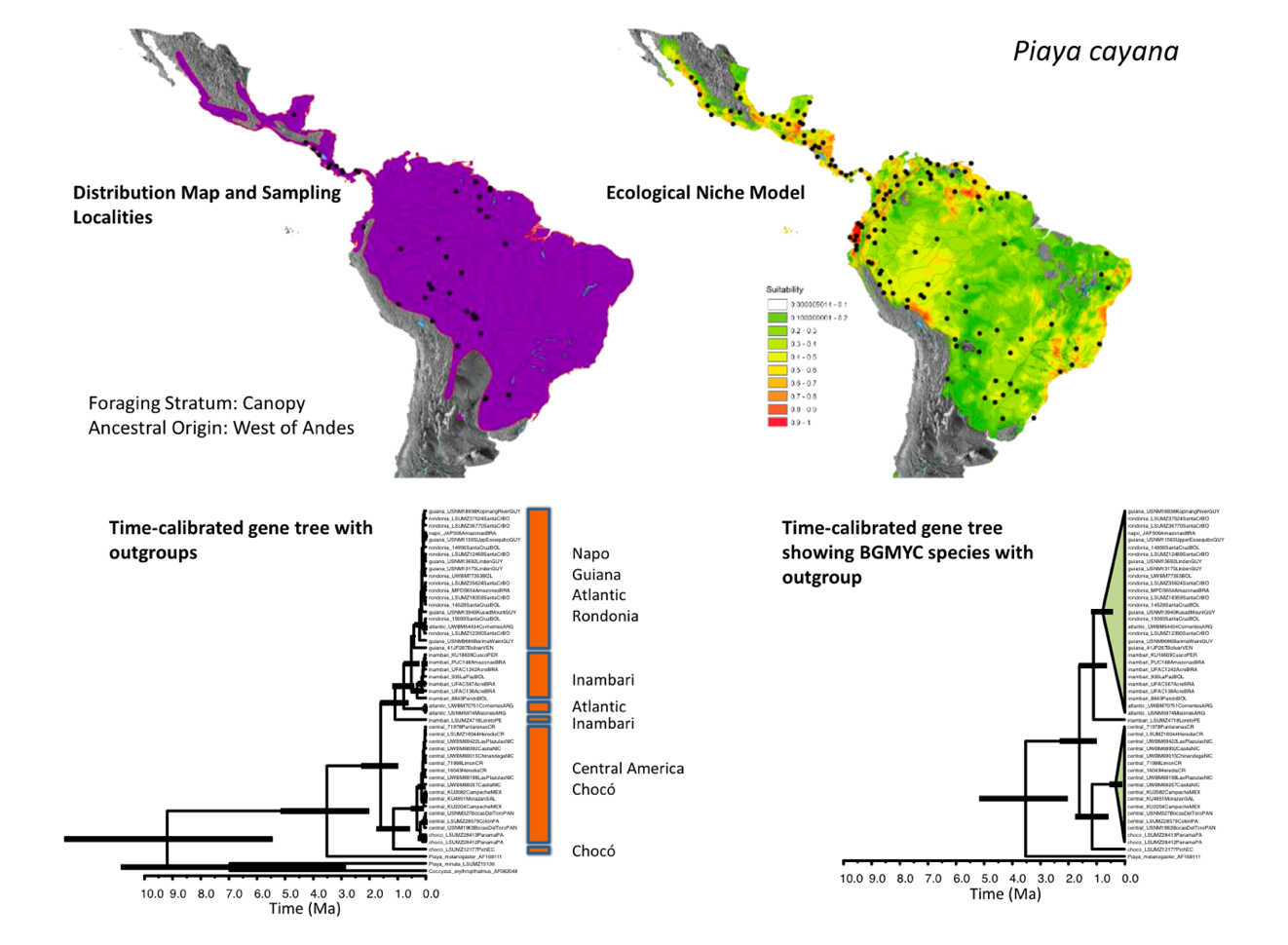

As

part of a broader study on tropical diversification, Smith et al. (2014)

sampled Piaya cayana from across its range, sequenced the ND2

mitochondrial gene, and used the species delimitation method bGMYC on the time-calibrated gene tree. Their results

largely agree with those of Sánchez‐González et al.

(2023), although the sampling is very different. Smith et al. (2014) sampled across much

of South and Middle America, but lacked samples from Colombia, eastern Brazil,

or western Mexico (i.e., mexicana). Smith et al. (2014) recovered four bGMYC

“species” (i.e., clades). Two of these clades contained most of their samples,

and corresponded to 1) Middle American samples (thermophila) and 2) most

of South America (much of the cayana group). The other two clades each

contained a single sample; the first was their sample from western Ecuador (nigricrissa)

which was sister to thermophila, and the second clade was a sample from

Loreto, Peru, in the northwestern Amazon. The divergence time estimates were

comparable between the two studies. These results are shown in the figure

below.

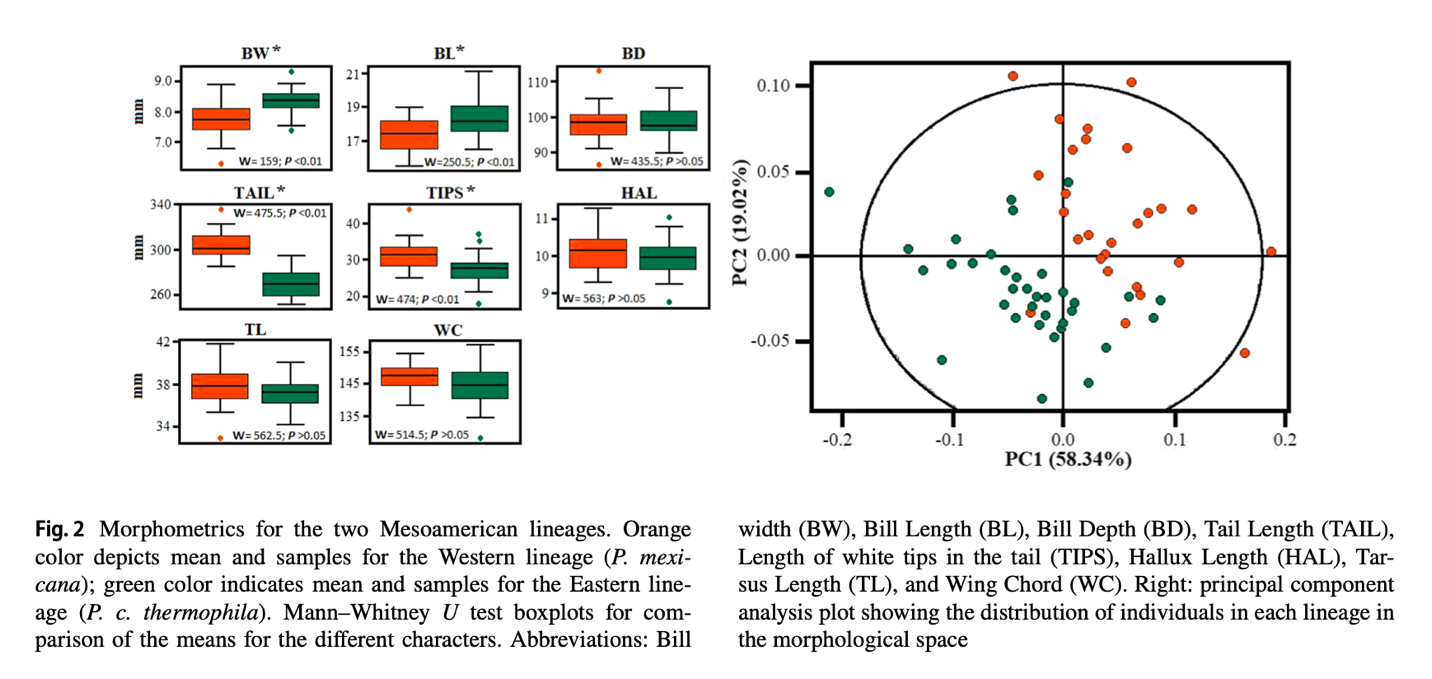

Sánchez‐González et al. (2023) also

measured specimens of thermophila and mexicana

and found significant average differences in four characters: bill width, bill

length, tail length, and the length of the white tips on the tail feathers. A

PCA of these characters largely separated the two taxa, with some overlap.

These results are shown in their Figure 2 below.

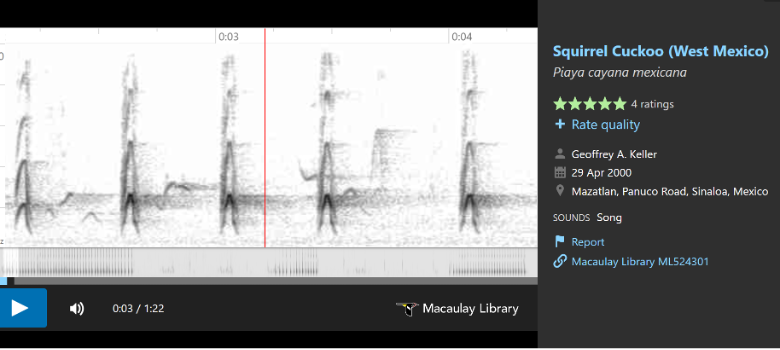

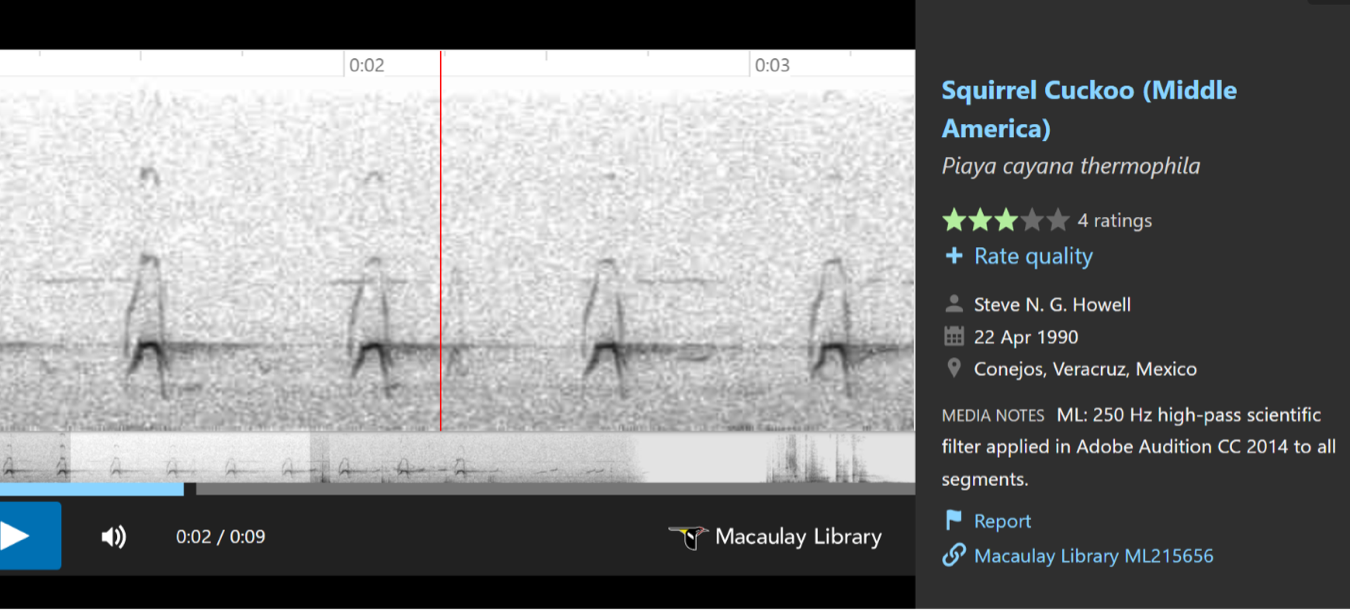

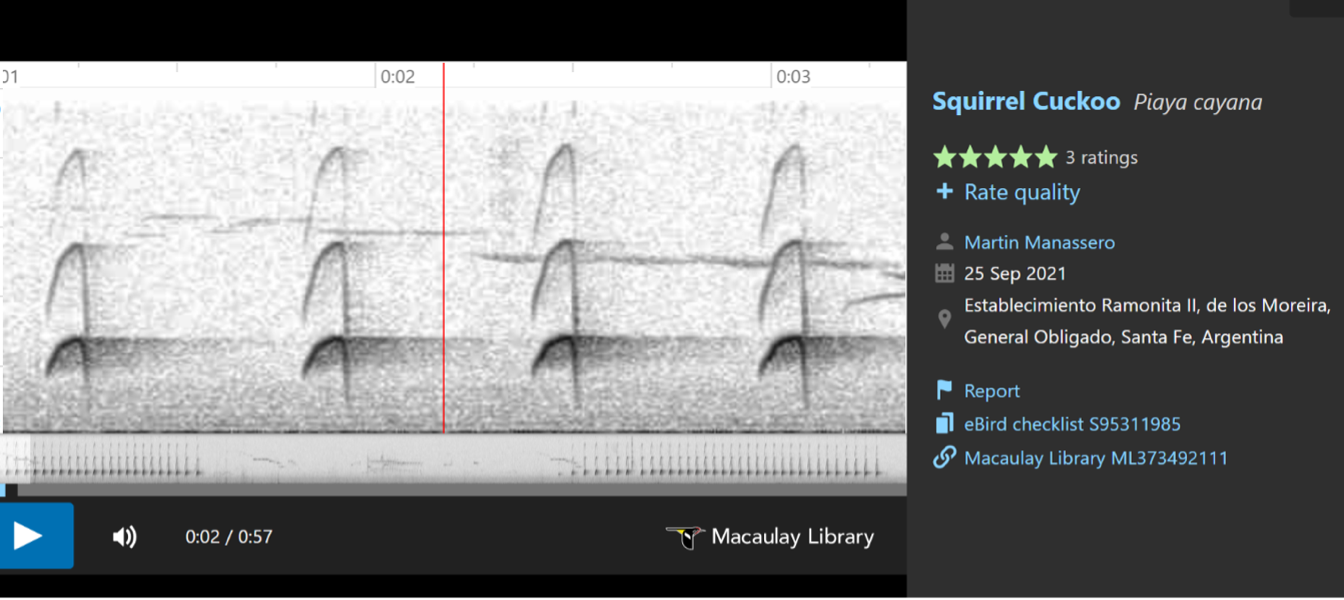

There

do not appear to be any published analyses of plumage or song from across the

distribution of P. cayana, but multiple references outlined below

discuss the plumages of each subspecies. Also, photos in 2022-B-11 nicely illustrate the plumage variation

in the group. As for song, we noted in 2022-B-11 that “the song of mexicana

appears to average higher pitched and more rapid than that of thermophila,

but some recordings of songs of thermophila seem to match recordings of mexicana”.

Pam Rasmussen in her WGAC proposal noted that mexicana “seems to have

the fastest ‘chick’ series with the sharpest (most vertical) notes, while South

American taxa seem to have more slurred (more diagonal) notes, and east Mexican

birds with longer, more resonant (less clipped) notes”, and included the following

sonograms to illustrate these differences.

In

addition, the limited genetic data suggest that if mexicana is split,

then a split of South American taxa should also be considered, as this is a

deeper split in the mitochondrial gene tree. This split is also currently being

considered by WGAC. However, neither Smith et al. (2014) nor Sánchez‐González et al. (2023) had

samples from anywhere in Colombia, nor from the zones of contact between Middle

American and South American groups. The sole sample from Venezuela in Smith et

al. (2014) comes from south of the Río Orinoco in the far east of the country.

Because it is very relevant to the species limits and range boundaries of

groups, we here include what information is available on the distributions of

the various forms that might come into contact. Fitzgerald et al. (2020) give

the following distributional statements (and plumage differences) for the

relevant subspecies that come into contact in Colombia and Venezuela. The first

two taxa are each considered monophyletic subspecies groups by Fitzgerald et

al. (2020):

thermophila Sclater 1859; type locality Jalapa,

Veracruz, Mexico. Occurs on the Gulf and Atlantic slopes from Mexico south to

Panama and northwestern Colombia. Relatively dark rufous-chestnut above; belly

and undertail coverts dark gray to black; underside of rectrices black, white

tips to rectrices relatively narrow.

nigricrissa (Cabanis 1862); type locality Babahoyo or Esmeraldas, Ecuador. Occurs in western Colombia

(east to the slopes of the central Andes), south of northwestern Peru. Similar

to thermophila, but plumage darker; belly and undertail coverts

blackish.

cayana group:

circe Bonaparte 1850; type

locality Caracas, Venezuela. Occurs in Venezuela, south of Lake Maracaibo.

Upperparts slightly more rufous than mehleri,

but paler than nominate cayana.

mehleri Bonaparte 1850; type

locality Santa Fé de Bogota (the same type locality

as mesura?!). Occurs in northeastern Colombia,

from the Gulf of Urabá to the Magdalena valley and the west slope of the

eastern Andes, east along the coast of northern Venezuela to the Paria

Peninsula. More rufous than mexicana, with a lighter throat and breast

that grade to light gray on the belly; underside of rectrices rufous.

insulana Hellmayr 1906; type

locality Chaguaranas, Trinidad. Trinidad. Similar to cayana,

but undertail coverts black.

cayana (Linné 1766); type

locality Cayenne. Widespread, from eastern and southern Venezuela east through

the Guyanas, south to Brazil to the north bank of the

lower Amazon. Belly ashy gray; undertail coverts darker gray; colors otherwise

similar to thermophila except that the belly and undertail coverts are

not as dark; underside of rectrices black with white tips.

mesura (Cabanis and Heine

1863); type locality Bogotá, Colombia. Occurs in eastern Colombia, Ecuador, and

Peru. Similar in plumage to nigricrissa; smaller, but with overlap in

size.

Chapman

(1917) included more detail on the distribution of the Colombian taxa, and,

critically, suggested an area of potential contact between nigricrissa

and mehleri based on a fairly extensive

specimen series. Some critical passages from Chapman (1917) are below. Note

that “columbiana” is currently regarded as a synonym of mehleri.

Piaya cayana columbiana [=mehleri]

After comparison with an essentially

topotypical series from Santa Marta, I refer to this form our specimens from

the Magdalena Valley and western slope of the Eastern Andes as far south as Chicoral. These birds have the ventral region darker, the

rectrices are blacker, and a bird from Puerto Berrio

is deeper above than true columbiana. They thus show an approach toward P.

c. nigricrissa of western Colombia, which, however, is darker above and has

much more black on the ventral region.

Piaya cayana mesura

Two forms of Piaya inhabit the Bogotá

region, P. c. mesura and P. c. columbiana.

The first occurs on the eastern slopes of the Eastern Andes, and, singularly

enough, on both eastern and western slopes of the Andes at the head of the

Magdalena Valley; the second, occurs on the slopes of the Eastern Andes west of

Bogotá and in the Magdalena Valley at least as far south as Chicoral.

Piaya cayana nigricrissa

Inhabits the Tropical and Subtropical Zones in

western Ecuador and western Colombia, extending in Colombia eastward to the

eastern slope of the Central Andes. Specimens from Antioquia east of the

Western Andes approach columbiana, but on the whole, are nearer nigricrissa.

Chapman

(1917) notes that mesura is “distinguished

chiefly by the comparative blackness of all but the central tail-feathers, seen

from below, a character that at once separates it from the other Colombian

forms”. This character is apparent in the photo of mesura

in proposal 2022-B-11, especially in comparison to the specimen of nigricrissa.

This, combined with Chapman’s statement of intermediates between nigricrissa

and columbiana [=mehleri] in

Antioquia, suggests hybridization in central Colombia, likely between

populations in the Magdalena Valley (mehleri)

and the eastern slope of the central Andes (nigricrissa). As noted

above, Chapman (1917) also indicates that samples at the far southern end of

the Magdalena Valley pertain to mesura, which

crosses over the eastern Andes in this region. An additional potential contact

zone is in low passes in southern Ecuador (vicinity of Loja). It is not clear

whether there are intergrades in these areas, which do not appear to be located

at ecotones as in mexicana vs. thermophila.

Another

point, overlooked in 2022-B-11, is that mehleri

of the northern coast of Colombia (and the taxon that presumably meets thermophila

in northwestern Colombia) is pale rufous in color similar to mexicana.

This was noted by Stone (1908), who stated that mehleri

“is indistinguishable from mexicana above, and differs below only in the

greater amount of black shading on the rectrices; the greatest difference is

found in the much larger bill”. Given that the very rufous coloration of mexicana

is one of the primary characters suggesting species status for this taxon, this

is of particular interest. Although proposal 2022-B-11 highlighted the similar

pale rufous plumage of mexicana and pallescens of eastern Brazil,

no specimen photos of mehleri were included in

that proposal. The similar pale rufous coloration of mehleri

and mexicana is readily apparent in photos, although the undertail of mehleri is darker overall, being more similar to

other taxa in the cayana group in this regard. Photos of mehleri from northern Colombia:

https://macaulaylibrary.org/asset/206165711

https://macaulaylibrary.org/asset/366888881

https://macaulaylibrary.org/asset/393722091

Another

critical issue in overlooked in 2022-B-11 are differences in orbital skin

color, something noted by Pam Rasmussen in her WGAC proposal and described in

detail by Fitzgerald et al. (2020), but of course not apparent in specimens. In

fact, this character might be a much better indicator of species limits in the

group than overall plumage coloration, the latter of which seems to vary

considerably based on climate. Based on Schulenberg et al. (2007), Restall et

al. (2007), Fitzgerald et al. (2020), and available photos online, variation in

orbital skin color is as follows: blue-gray in mexicana; greenish-yellow

in thermophila, nigricrissa, mehleri, circe, and insulana;

and red in mesura, cayana (of the Guiana

Shield), and all remaining South American taxa. Based on photos, it appears

that populations with red orbital skin (mesura

and cayana) approach those with greenish-yellow orbital skin (nigricrissa,

circe, and mehleri)

in multiple places with very abrupt turnover. These areas mostly correspond

quite closely to the subspecies turnovers noted by Chapman (1917). These

include in the southern Magdalena Valley near Neiva (greenish yellow mehleri to the north, red mesura

to the south/east), the Rio Orinoco in Venezuela (greenish yellow circe on the left bank, and red cayana on the

right bank), and perhaps somewhere across the Rio Meta in the dry llanos Orientales of Colombia. The two (here mehleri

and mesura) also appear to turn over within a

few kilometers along the eastern flank of the eastern Andes near Yopal, Casanare, Colombia: https://macaulaylibrary.org/asset/285186601 versus https://macaulaylibrary.org/asset/586198261. eBird photos from

Casanare department, Colombia in the dry llanos show a mix of red and

greenish-yellow orbital rings in a patchwork, raising the possibility of local

sympatry. We have found just one individual (from adjacent northern Meta

department) that appears to show some green in an otherwise red orbital ring,

which would argue for some limited hybridization in this area: https://macaulaylibrary.org/asset/217105071https://macaulaylibrary.org/asset/217105071. There is also abrupt turnover in this character within a

few kilometers across low Andean passes near Loja in southern Ecuador (here nigricrissa

and mesura). See https://macaulaylibrary.org/asset/518051361 versus https://macaulaylibrary.org/asset/600766311.

This

would all suggest that if a split is implemented, the division of only thermophila

and nigricrissa from cayana is not a good course of action. In

fact, we suggest based on orbital ring color and what appear to be very sharp

turnovers between populations with red vs greenish-yellow orbital rings, that a

group comprised of circe, mehleri, insulana, thermophila

and nigricrissa could be split from P. cayana. In this case, the

northern species would be either P. circe or P.

mehleri, both described by Bonaparte in 1850,

rather than P. thermophila Sclater, 1859. Because Bonaparte (1850)

described circe and mehleri

in the same publication, a first reviser action would likely be required to

establish priority; we will refer to this species as P. “circe”

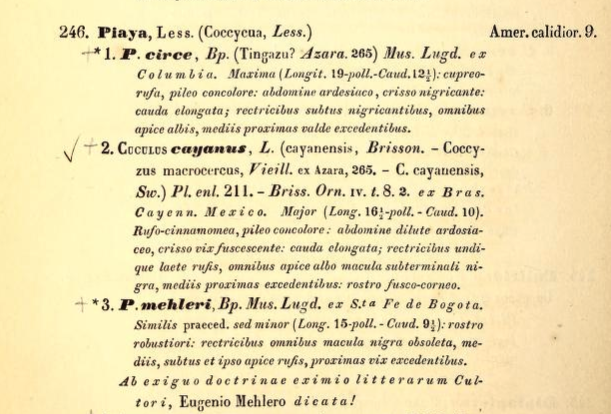

through the rest of this proposal. Bonaparte’s description of these

taxa is here:

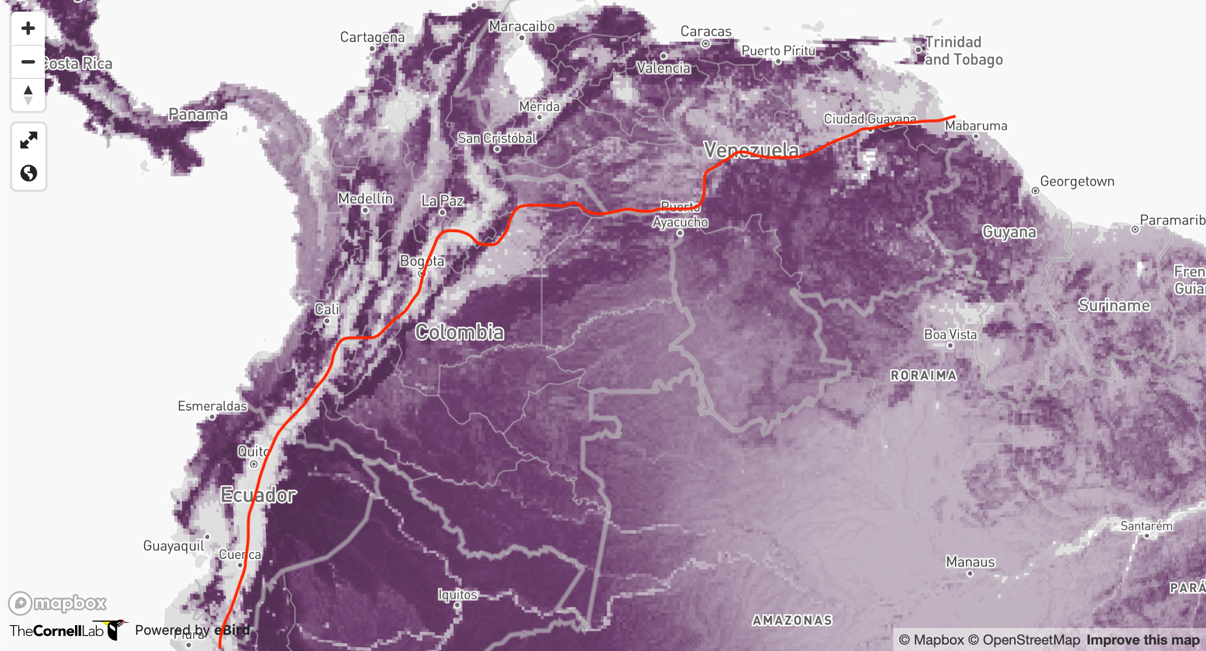

To

provide a better visualization of where these taxa come into contact in

Colombia, below is the eBird abundance map (https://science.ebird.org/en/status-and-trends/species/squcuc1/abundance-map), with a red line

approximately delineating the cayana and “circe”

groups based on the distributional statements above. The abundances do seem to

match the number of eBird records in these regions, so are likely a decent

representation of the distribution. However, it would be great to get some

insight on this issue from Colombian and Venezuelan ornithologists who are more

familiar with this species in these potential areas of contact. If implementing

this split, the range boundary between P. “circe”

and P. cayana would be approximately as such:

In

reading the older literature on this group there is a bewildering number of

synonymies for each taxon, which is confounded by multiple taxa described from

“Bogota” skins, and multiple examples of a name being applied to different

populations by different authors. Much of this was sorted out by Chapman (1917)

and Junge (1937) but we think some errors persist. As

an example of this confusion, Stone (1908) applied mehleri

Bonaparte, 1850, to the Central American populations (now considered thermophila)

based on Sclater’s (1860) determination that the type locality was in fact

“Central America”, not “Santa Fé de Bogota” as

originally given by Bonaparte. Chapman (1917) then applied columbiana

(type locality Cartagena, Colombia) to the northern Colombian population,

considering mehleri Allen, 1900 (type

locality Santa Marta, Colombia), as a synonym, apparently overlooking mehleri Bonaparte, 1850. Later authors (e.g.,

Fitzgerald et al. 2020) applied mehleri

Bonaparte, 1850, to the populations of coastal northern Colombia and Venezuela

(i.e., columbiana of Chapman 1917). We mention this because we have not

undertaken a thorough review of all synonymies for these taxa, and trust that

later authors (e.g., Fitzgerald et al. 2020) have resolved these issues

satisfactorily, such that if these taxa are split the correct names are applied

to the daughter species.

One

issue that we have attempted to clarify involves the type localities of circe and mehleri.

Junge (1937) sorted out these type localities by

reviewing the collecting localities on the tags of the type specimens. In

contrast to earlier authors (see previous paragraph), he reported that the type

of circe was collected in Caracas,

Venezuela, and mehleri in Cartagena, Colombia.

Both of these localities contain pale rufous birds with greenish-yellow orbital

rings, so can be confidently associated with the northern group, not with the cayana

group, based on orbital ring color. Phelps and Phelps (1958) thought that

the type locality of circe was likely

Mérida, Venezuela, and reported the distribution as being south of Lago

Maracaibo, which seems to be the basis of the distributional statement in

Fitzgerald et al. (2020). However, Junge (1937)

compared the type of circe (from Caracas) to

specimens collected “south of Lago Maracaibo” and concluded that they were

similar enough to be considered same taxon. So, we suspect that it is circe that is found from western Venezuela (near

Lago Maracaibo) as far east as the Delta Amacuro. Subspecies mehleri would then be restricted to northern Colombia

and the Magdalena Valley.

Effect on SACC area:

Splitting

“circe” from cayana would result in one

additional species for the SACC area. Splitting mexicana from cayana

would not result in any additional species for the SACC area, as mexicana

is extralimital. However, we think that it is still worthwhile for SACC to

consider this split, as it would be better to consider species limits in the

complex as a whole, based on current information.

Please

vote on the following issues:

A.

Treat Piaya mexicana as a separate species from P. cayana

B.

Treat Piaya “circe” (including thermophila,

nigricrissa, mehleri, and insulana)

as a separate species from P. cayana

Recommendation:

This

is clearly a borderline case with suboptimal data [and a potential

nomenclatural issue], but we tentatively recommend a YES on both A and

B.

The

split of mexicana would be based on the mitochondrial genetic

differences, consistent plumage differences, morphometric differences, possible

sharper call notes, and narrow contact zone with thermophila. This is

the treatment recommended by Sánchez‐González et al. (2023).

This contact zone does appear to be narrow and occurs across a sharp ecotone,

albeit with a few intermediates. However, there are still no formal analyses of

vocal or plumage data. The vocal information mentioned above does seem to indicate

a sharper, higher-pitched call note in mexicana, but it is unknown

whether these differences are diagnosable, if they’re affected by the level of

agitation of the bird, or if they’re relevant in playback trials. The plumage

differences between mexicana and

thermophila are readily apparent visually (especially the rufous undertail

of mexicana), but the overall pale rufous plumage coloration is repeated in

other taxa such as mehleri and pallescens.

The morphometric data from Sánchez‐González et al. (2023)

for mexicana vs. thermophila do show average differences between

the two groups, but with overlap. The data show that the longer tail of mexicana is closer to being diagnostic

versus thermophila than are other characters (i.e., less

overlap in the box plots). However, splitting mexicana from cayana, and not splitting thermophila, would render cayana paraphyletic for

the mitochondrial gene tree. This may not be an issue, given gene tree /

species tree issues, but nuclear DNA data would be preferable. There are also

little data on gene flow across the contact zone. If the Nm

values in Sánchez‐González et al. (2023) are reliable (which we

posit that they are not), there is little gene flow across the contact zone (Nm = 0.05). In short, there appear to be diagnosable differences across a

small contact zone, but it is not clear whether these differences correspond to

biological species.

In

contrast, as noted above, there are still many unanswered questions regarding

the contact zone between the “circe” and

cayana groups. Most importantly, there are no genetic samples from

potential contact zones in Venezuela, Colombia, or Ecuador. However, given the

available data, splitting “circe” and

mexicana would maintain monophyly for the mitochondrial gene tree and split

two clades that are 1.2 – 1.7 million years divergent. The data from Smith et

al. (2014) suggest that there is a mitochondrial clade in northern Peru that is

distinct from the rest of South America, and whether this clade is the same as

the one found in Colombia is unknown. We think that the critical data are from

the very abrupt turnover between taxa with red orbital rings from those with

greenish-yellow orbital rings. Analyses of these contact zones do seem critical

to determining species limits, but we think the data at hand tip the scales

towards valid species. However, the sonograms of the thermophila and

cayana groups shown above look fairly similar to us. There is also

still the issue of the extensive plumage variation within the cayana group

even if the “circe” group is split, with pale

bellied and pale rufous taxa (e.g., pallescens) and dark-vented (e.g., macroura)

taxa that at least superficially resemble the Middle American and northern

South American taxa.

The

nomenclatural issue of circe and mehleri is problematic. As stated above, because circe and mehleri

were published simultaneously, a first reviser action would be necessary to

decide which species name would apply if this northern group were split from P.

cayana. We think it is worth considering this novel species treatment given

the available data, but it may be worth waiting until for a publication to sort

out the nomenclatural issues before implementing the split.

The

way that the voting options are structured, there are a few other possible

voting solutions. The first is a YES on A and a NO on B, which would render P.

cayana paraphyletic in the mitochondrial gene trees. The other option would

be a NO on A and a YES on B, which would prioritize the deeper split in the

mitochondrial gene tree and the more obvious difference in orbital ring color

(the blue-gray orbital ring of mexicana is somewhat more similar to the

greenish-yellow of thermophila). Note that if this latter option is

adopted that the species would be P. mexicana (Swainson, 1827), which

has priority over circe Bonaparte,

1850.

Note

also that the WGAC is considering splitting just thermophila and nigricrissa

from the remainder of the South American taxa. We do not consider this a viable

solution to this taxonomic problem, and are not including it as a voting

option.

If

any of these splits are adopted,

an English name proposal should be drafted to address the new names, preferably

in coordination with the NACC. We tentatively recommend Mexican Squirrel-Cuckoo

for mexicana, following Chapman (1917). Although a bit of a mouthful,

Chapman (1917) used Central American Squirrel-Cuckoo for thermophila (although

nigricrissa occurs in South America), but this name would not be

appropriate for the more widespread P. circe.

One option, though not ideal, could be Northern Squirrel-Cuckoo for “circe” and Southern Squirrel-Cuckoo for cayana.

South American Squirrel-Cuckoo could also work for cayana.

Literature Cited:

Binford, L. C. 1989. A

Distributional Survey of the Birds of the Mexican State of Oaxaca.

Ornithological Monographs 43. American Ornithologists’ Union. Washington, DC,

USA.

Bonaparte, C.L. 1850.

Conspectus Generum Avium. Lugduni

Batavorum. Apud E. J. Brill, Acadamiae

Typographum.

https://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/item/141467#page/186/mode/1up

Chapman, F.M. 1917. The

distribution of bird-life in Colombia; a contribution to a biological survey of

South America. Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History. Volume 36. https://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/item/117614#page/407/mode/1up

Cory, C. B. 1919.

Catalogue of birds of the Americas, part II. Field Museum of Natural History

Zoological Series Vol. XIII. Chicago, USA.

Fitzgerald, J., T. S.

Schulenberg, and G. F. Seeholzer. 2020. Squirrel Cuckoo (Piaya cayana), version 1.0. In Birds of the World (T. S.

Schulenberg, Editor). Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, NY, USA. https://doi.org/10.2173/bow.squcuc1.01

Junge, G.C.A. 1937. On

Bonaparte’s types of the cuckoos belonging to the genus Piaya. Zoologische Mededelingen

19:186–193.

Navarro-Sigüenza, A.G.

and A.T. Peterson. 2004. An alternative species taxonomy of the birds of

Mexico. Biota Neotropica 4(2):1–32.

http://www.biotaneotropica.org.br/v4n2/pt/fullpaper?bn03504022004+en

Peters, J. L. 1940.

Check-list of birds of the world. Vol. 4. Museum of Comparative Zoology at

Harvard College.

Phelps, W.H., and W.H.

Phelps, Jr. 1958. Lista de las Aves de Venezuela con su

Distribución. Tomo II, Parte I. No Passeriformes. Editorial Sucre, Caracas.

Restall, R., C. Rodner,

and M. Lentino. 2007. Birds of northern South America; an identification guide.

Volume 1: species accounts. Yale University Press.

Ridgely, R.S., and P.J.

Greenfield. 2001. The birds of Ecuador. Vol. 2. Cornell University Press.

Ridgway, R. 1916. The

birds of North and Middle America. Part VII. Bulletin of the United States

National Museum. No. 50.

Sánchez‐González,

L.A., H. Cayetano, D.A. Prieto‐Torres, O.R. Rojas‐Soto,

and A.G. Navarro‐Sigüenza. 2023. The role of ecological and

geographical drivers of lineage diversification in the Squirrel Cuckoo Piaya

cayana in Mexico: a mitochondrial DNA perspective. Journal of Ornithology

164:37–53. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10336-022-02008-w

Schulenberg, T.S., D.F.

Stotz, D.F. Lane, J.P. O’Neill, and T.A. Parker III. 2007. Birds of Peru,

revised and updated edition. Princeton University Press.

Stone, W. 1908. A

review of the genus Piaya Lesson. Proceedings of the Academy of

Philadelphia 60(3):492–501. https://www.jstor.org/stable/4063306

Swainson, W. 1827. A

synopsis of the birds discovered in Mexico by W. Bullock, F. L. S., and H. S.,

Mr. William Bullock. Philos. Mag. (New Series) 1: 364–369, 433–442. https://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/item/53108#page/456/mode/1up

Whitlock, M., and D.

McCauley. 1999. Indirect measures of gene flow and migration: FST≠1/(4Nm+1).

Heredity 82:117–125. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.hdy.6884960

Oscar Johnson,

September 2023

Comments from Remsen: “NO. Highly conflicted on this

one. Borderline indeed. If the data assembled in the proposal were in

the form of a peer-reviewed publication, I would vote YES because I think it

more closely approximates species limits than does the current broadly defined,

Peters-based single species.

“A thorough study

that sampled all taxa might reveal some conflicts with a three-species

taxonomy, and it is always easy to require more data before making splits in a

complex like this one. But a “do no harm” conservative approach might be the

wisest thing to do in a case like this given the data gaps. We already know that basing taxonomy on mtDNA

gene trees is unwise, so I don’t trust the basics of the tree typology. And the contact zones outside of the mexicana-thermophila

one are poorly characterized. And then

there’s the circe-mehleri nomenclature

problem.

“Given the

absence of any sign of free gene flow between extralimital mexicana and thermophila,

I personally would consider that sufficient evidence for a species split, but

that is out of the SACC realm. Given the

orbital ring color differences outlined in the proposal, I think it also might

be safe to extrapolate from the mexicana-thermophila situation to

the South American situation. If all

this were summarized in a publication rather than NACC + WGAC proposals, I

would favor a YES vote, especially because that would also provide the first

revisor opportunity.”

Comments from Robbins: “NO. This

is indeed a difficult situation to evaluate, at any level. As Oscar summarizes

in paragraph two of the recommendation, a number of issues need to be clarified

with just splitting off mexicana.

I’m not convinced that plumage differences have any relevance in species

limits, and I even wonder if orbital ring color is important. Moreover, as Oscar points out the vocal

comparisons may not have been standardized, i.e., comparing analogous calls

under similar conditions, and I agree they not only look similar in a

spectrogram but sound similar. It should

also be noted that only one of several vocalizations that Piaya give

have been looked at. Finally, I would like to see a nuclear DNA data set that

helps guide the way forward. Thus, for now, I vote NO.”

Comments

from Lane:

“NO to both A and B. Having some personal experience

with both Middle American/trans-Andean groups, and extensive experience with cis-Andean

groups, the main characters that define them are not strong enough for me to

see them as species-level. The cis/trans split seems like it is the one we

should be looking at first, as it clearly is the older split, and the orbital

color is a character that doesn't seem as affected by Gloger's Rule as the

plumage, but even there, I'm underwhelmed by the vocal differences, which to me

suggest that these groups simply aren't that divergent. I wonder if work in the

Llanos of Colombia and Venezuela might elucidate how the two groups interact?

As indicated in the proposal, there has been effectively no real effort yet to

quantify vocal differences, and whereas the mitochondrial groups certainly

indicate clades that could be worthy of recognition, my mind doesn't register

them as so distinctive as to warrant species status.”

Comments from Zimmer:

“A. Treat

Piaya Mexicana as a separate species from P. cayana. NO.

“B. Treat Piaya “circe” (including thermophila, nigricrissa, mehleri, and insulana)

as a separate species from P. cayana. NO.

“This

is a tough call for me, because, from the evidence presented in the Proposal, I

suspect that the proposed three-way split is actually the most reflective of

the relationships of these various taxa.

The abrupt turn-over in orbital ring color between the cis-trans groups

is particularly compelling to me, as is the absence of any sign of free gene

flow between mexicana and parapatric thermophila. However, I

agree with Mark that the plumage differences and tail length differences,

although pronounced between some taxon-pairs, when considered as a whole, are

all over the map, and may not have any relevance in species limits. After all, plumage distinctions of tail

pattern, belly/vent coloration, and overall color saturation of upperparts and

underparts, and tail length of P. melanogaster seem to overlap or at

least closely approach, one or more named subspecies of “Squirrel Cuckoo”, but

bare parts colors and head/facial pattern are dramatically different (which, in

my mind, lends further significance to the cis-trans orbital skin color

differences in the cayana-group).

The larger issue in my mind, is the lack of any well-sampled vocal

analysis that compares clearly homologous vocalizations. As Mark notes, members of this complex have

multiple types of vocalizations, and, although, as alluded to by both Mark and

Dan, the vocal distinctions may not be impressively obvious on first

reflection, I suspect that a comprehensive analysis (both quantitative and

qualitative) will reveal some distinctions that are concordant with the

proposed splits. Looking

again at P. melanogaster, there are several different types of

vocalizations in that species as well, and most/all are similar enough to be at

least recognizably analogous to the various vocalizations within cayana

(sensu lato), and yet the birds themselves, as well as a rigorous vocal

analysis, would have little trouble making the distinction. I’ve also noticed a seeming difference in the

frequency of usage of homologous vocalizations between different populations of

Squirrel Cuckoos, particularly with respect to Atlantic Forest populations

versus Amazonian and Central American populations, which further underscores

the need for a vocal analysis that considers the entire range of the complex. Taken in sum, that leaves me as a reluctant

NO vote for now, but looking forward to a published analysis of vocalizations

that, I predict, will flip my vote to a YES.”

Comments

from Bonaccorso:

“A.

NO. But very close to a YES. The mitochondrial tree

from Sanchez-Gonzalez et al (2023), based on a good sampling of P.c.

thermophila and P. mexicana (at least for Mexico) and is very well supported, but I

think nuclear evidence should provide the definitive answer. Although

morphological measurements overlap, plumage variation seems clear, especially

regarding tail color. I agree that voice comparison needs to be standardized.”

“B. NO. It is too risky to make any decision without proper

genetic sampling of all the populations, and enough samples from each

population. For these, there are no formal morphometric or vocal analyses and

no comprehension of the potential contact zone.”

Comments from Claramunt: “NO. I’m persuaded by de evidence

for species status for mexicana. Here we have two populations with clear

phenotypic differences in plumage color, tail length, and skin color, that are

reciprocally monophyletic in their mtDNA genealogies, and show an extensive

contact zone with barely any evidence of potential hybridization. This pattern

would be highly implausible if the two taxa were not largely reproductively

isolated. However, the genetic evidence suggests that the separation of mexicana

would require further splits in the other taxon in order to avoid a paraphyletic

group. But the situation in this other group is complex. I agree with Van in

that situations of this complexity require a peer-review publication. I would

need to see maps with the distribution of subspecies and, more importantly,

maps of distributions of characters. And the nomenclatorial issues would need

to be worked out. I think there is great potential for this to become a

three-way split with periorbital skin color separating two South American

forms. But I would like to see the evidence more clearly.”

Comments

from Stiles:

“NO for now – this species could be split into two or more species, but the

bewildering number of noncongruent characters and holes or uncertainty in the

distributional limits of some forms and hence, in locating possible areas of

contact all add up to a puzzle with too many missing pieces. Just how one

potentially useful feature, eyering color, needs to be looked at with more

detail (hopefully, I may be able to look at the distributions of a number of

Colombian specimens here) – but for now, no clear decision seems possible.”