Proposal (995) to South

American Classification Committee

(Note from Remsen: This proposal was submitted to the North American

Classification Committee and passed, and it is submitted here with permission

from Eric VanderWerf. Note that brewsteri,

as represented by the subspecies etesiaca, breeds in the SACC area on

Isla Gorgona, Colombia.)

Treat Sula brewsteri as a

separate species from Brown Booby S.

leucogaster (Part A), and if Part

A passes, establish English name for Sula

brewsteri (Part B)

Part A.

Background:

Note: much

of the background information below is from VanderWerf et al. (2023)

The Brown Booby (Sula leucogaster) is a pantropical seabird found in the Pacific,

Atlantic, and Indian Oceans that exhibits geographic morphological variation.

Five subspecies have been described based on differences in color of the

plumage, bill, and facial skin (Table 1; Nelson 1978, VanderWerf 2018a,

Schreiber & Norton 2020). Sula l.

plotus has the largest geographic range, from the Red Sea and Indian Ocean

east to the central Pacific. In both sexes of S. l. plotus, the head is

dark brown, and the bill is yellow (females) or bluish-yellow (males). The

nominate subspecies, S. l. leucogaster,

occurs in the Atlantic and Caribbean and is similar to plotus but has a more pinkish bill. The form of Brown Booby

occurring in the eastern Pacific, S. l.

brewsteri, is the most distinctive morphologically and originally was

described as a separate species called Brewster’s Booby (S. brewsteri; Goss 1888). Male S.

l. brewsteri have a geographically variable white head, a more grayish-blue

bill, and a more greenish-blue gular pouch. In the Gulf of California and the

western coast of Mexico south to the Revillagigedo Islands, male S. l. brewsteri have a white head and a

pale brown upper neck. On some islands off Central America and South America,

the white on the head of males is restricted to the forehead, and this form

sometimes is considered a separate subspecies, S. l. etesiaca, but also has been grouped with S. l. brewsteri (Harrison 1983, Schreiber & Norton 2020). The

form breeding on Clipperton Island is the palest, with the entire head and neck

white in males, and is sometimes referred to as S. l. nesiotes (Heller and Snodgrass 1901, Pitman & Balance

2002, Schreiber & Norton 2020).

As noted above, Brewster’s Booby originally was

described as a species, S. brewsteri,

by Goss (1888) based on type specimens from San Pedro Mártir Island, Mexico. In

the description, Goss noted that characteristics of the species included the

pale color of the head and neck, especially in the male, a dark brown iris with

a narrow outer ring of grayish-white, and “unfeathered parts also differently

colored.” In 1944, S. l. brewsteri was lumped with other forms of

the Brown Booby (Wetmore et al. 1944), who cited “Peters, checklist, 1, 1931”

and Wetmore (1939) as justification for the lump. Wetmore (1939) stated that

“while apparently uniform over large areas of the tropical oceans of the world

there are three (barely possibly four) races of Sula leucogaster to be recognized…on the Pacific coast of the

Americas… These differ from all other subspecies of the species.” Wetmore

(1939) discusses at length the variation among the forms in the eastern

Pacific, which seems to support their distinction, and did not offer any

explanation for why S. l. brewsteri

should be lumped with other forms of the Brown Booby, yet he did so, and this,

paradoxically, served as the basis for the lumping by Wetmore et al (1944).

Genetic population structure of Brown Boobies

largely matches patterns of morphological variation (Steeves et al. 2003,

Morris-Pocock et al. 2010, 2011). Mitochondrial haplotypes were not shared

between the eastern and central Pacific or between the eastern Pacific and

Caribbean (Steeves et al. 2003), and colonies grouped into four major,

genetically differentiated populations; Caribbean, central Atlantic,

Indo-central Pacific, and eastern Pacific (Morris-Pocock et al. 2011). The

eastern Pacific population was found to be the most different genetically and

was estimated to have diverged from all other populations approximately one

million years ago (Morris-Pocock et al. 2011). These populations have diverged

because of a combination of physical barriers (the Isthmus of Panama and the

Eastern Pacific Basin) and a behavioral tendency in the Brown Booby to forage

closer to shore than other booby species (Steeves et al. 2003).

Table 1. Distinguishing characteristics of Brown Booby subspecies.

Copied from VanderWerf et al. (2023).

|

Character |

plotus |

leucogaster |

brewsteri |

nesiotes |

etesiaca |

|

Male

head color |

brown |

brown |

white

head and upper neck |

white

head and entire neck |

white

forehead |

|

Female

head color |

brown |

brown |

whitish

forehead |

whitish

forehead |

whitish

forehead |

|

Male

bill color |

bluish-yellow |

bluish-yellow |

grayish-blue |

grayish-blue |

grayish-blue |

|

Female

bill color |

yellow |

pinkish

yellow |

pinkish

yellow |

pinkish

yellow |

pinkish

yellow |

|

Ventral lesser wing coverts |

white |

white |

white

with brown bar |

white

with brown bar |

? |

New Information:

Three types of new information support

recognizing Brewster’s Booby as a separate species: 1) morphological data

demonstrating that males and females of the subspecies differ in additional

ways not previously recognized; 2) behavioral data on pairing patterns showing

that interbreeding between plotus and

brewsteri is rare despite increasing

sympatry; 3) information on behavioral ecology demonstrating that the

morphological differences between plotus

and brewsteri act as a reproductive

isolating mechanism that inhibits interbreeding. The information on behavioral

ecology is not that new, but its relevance to taxonomy does not seem to have

been considered previously.

1. Morphology. Descriptions of Brown Booby subspecies relied

primarily on the appearance of males and did not consider the appearance of

females. VanderWerf (2018) described differences between females of the

subspecies that can be used to identify them in the field: female S. l. brewsteri have a pinker bill and

paler forehead than female S. l. plotus.

Females can be distinguished as reliably as males of these subspecies, although

the characters used to identify females are less obvious. VanderWerf (2018) also

showed that the underwing coverts in both sexes of S. l. brewsteri are less extensively white than those of S. l. plotus.

I have unpublished data showing that iris color

and bill curvature also differ among Brown Booby subspecies, but I am still in

the process of collecting and analyzing these data. I do not think this

information about additional distinguishing characters is needed to assess the

taxonomy of Brown Boobies, but it will be useful in their identification.

2. Pairing Patterns. The Eastern Pacific Basin is

an enormous, island-free ocean area that for millennia has formed a physical

barrier to dispersal and promoted geographic differentiation of many seabirds,

including the Brown Booby (Avise et al. 2000, Steeves et al. 2003, Morris-Pocock

et al. 2011). Recently, Brown Boobies have been overcoming the barrier posed by

the Eastern Pacific Basin and have dispersed eastward and westward across the

Pacific. VanderWerf et al. (2008) documented an increasing number of S. l. brewsteri present and breeding in

the central Pacific, and Kohno and Mizutani (2011)

documented the occurrence and breeding of S.

l. brewsteri males on islands near Japan. Isla San Benedicto,

in the Revillagigedo Islands off the west coast of Mexico, was recolonized by

Brown Boobies following a volcanic eruption in 1952, and both plotus and brewsteri males are present and breeding on the island (Pitman and

Ballance 2002, Morris-Pocock et al. 2011). VanderWerf et al. (2023) showed that

the westward expansion of brewsteri

has continued, resulting in even greater sympatry between the subspecies. The

increasing sympatry of S. l. brewsteri

and S. l. plotus could result in gene

flow and erosion of differentiation between these forms if they interbreed.

VanderWerf et al. (2023) also collected data on

pairing patterns in locations where both forms were known to breed together.

Quantitative data showed pairing by S. l.

brewsteri and S. l. plotus was

primarily assortative and interbreeding was rare (Table 2). At Moku Mana, Maui,

in 2021, there were fewer mixed pairs (zero), than expected by chance (X2

= 18.00, df = 1, p < 0.001). On Palmyra, there also were fewer mixed pairs

than expected by chance (X2 = 181.1, df = 1, p < 0.001), although

the sample size was small.

Anecdotal evidence also indicates that pairing

was primarily assortative, and that interbreeding was rare. On Wake Island in

2021, J. Gilardi observed 301 S. l. plotus pairs, six S. l.

brewsteri males, and one S. l.

brewsteri female, which was paired with one of the male S. l. brewsteri. The other five male S. l. brewsteri on Wake that year did

not attract a mate despite the presence of many unpaired S. l. plotus females. On Wake in 2022, J. Gilardi

observed that the brewsteri-brewsteri pair remained together and

raised another chick, but the other five brewsteri

males were unpaired. On Wake in 2023, J. Gilardi

observed seven male and four female brewsteri;

all 4 brewsteri females were paired

with brewsteri males, and the three

single brewsteri males built nests

but had no mate. On Moku Manu, Oahu, in May 2021, E. VanderWerf observed 93 S. l. plotus pairs and only one male and

one female S. l. brewsteri, which

were paired with each other and had a large chick. In September 2022, E.

VanderWerf observed five S. l. brewsteri

females on Moku Manu, all of which were unpaired. On Laysan, a nest with a male

brewsteri and female plotus was reported in 1998 (VanderWerf

et al. 2008), but re-examination of photos using identification criteria from

VanderWerf (2018) revealed that the female was S. l. brewsteri, representing another instance in which a male and

female brewsteri paired with each

other amid large numbers of male and female plotus.

The only instances of interbreeding occurred in locations where no female brewsteri

were present. On Midway, J. Plissner observed a male brewsteri x female plotus pair that raised a chick in 2020, when no female brewsteri were present. At Nakanokamishima Island, Japan, one brewsteri male paired and raised offspring with a plotus female from 2012-2014, but a

second brewsteri male was not able to

attract a mate despite frequent courtship attempts with plotus females (Kohno and Mizutani 2015).

Moku Mana Islet off the north coast of Maui is a

particularly interesting case. It was colonized by Brown Boobies recently, with

the first nest documented in 2004 by J. Penniman. In 2021, the island held

twice as many S. l. brewsteri pairs

as S. l. plotus pairs, with no mixed

pairs. This is the easternmost location in the Hawaiian Islands where Brown

Boobies breed, and the colonies were formed by individuals dispersing from the

east (S. l. brewsteri) and west (S. l. plotus), much like the situation

on Isla San Benedicto (Pitman and Ballance 2002).

Table 2. Pairing patterns of Brown Boobies by

subspecies, including only cases in which the identity of both parents was

known. Copied from VanderWerf et al. (2023).

|

Location |

Year |

Male

plotus + female plotus |

Male

plotus + female brewsteri |

Male brewsteri

+ female plotus |

Male brewsteri

+ female brewsteri |

|

Palmyra

Atoll † |

2014 |

~200 |

1 |

0 |

8 |

|

Moku

Mana |

2021 |

6 |

0 |

0 |

12 |

|

Moku

Manu |

2021 |

93 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

|

Laysan |

1998 |

~70 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

|

Midway ‡ |

2020 |

15 |

NA |

1 |

NA |

|

Wake

Island |

2023 |

301 |

0 |

0 |

4 |

|

Nakanokamishima ‡ |

2009 |

~900 |

NA |

1 |

NA |

†

At Palmyra 30 nests were observed with at least one brewsteri parent, but some nests were attended by a single parent

and the identity of the mate was unknown.

‡ At Midway and Nakanokamishima

no female brewsteri were

present so there was no chance of a mixed pair.

3. Reproductive Isolating Mechanisms. Mate

choice and breeding biology of Brewster’s Booby have been studied extensively

in Mexico, and this literature is important for understanding the pairing

patterns observed in the central Pacific. Most importantly, López-Rull et al. (2016) showed that male S. l. brewsteri with their head painted brown to look like male S. l.

plotus were treated aggressively by their mate and that the level of

aggression was higher at a colony closer to the zone of overlap between the

forms. They concluded that female dislike of foreign males may function as a

reproductive barrier in populations close to contact zones, where the risk of

possibly maladaptive hybridization is highest. Montoya et al. (2018) showed

that the carotenoid-based greenish-blue color of the gular pouch of males was

energetically expensive to maintain, that its chroma peaked during courtship,

and that it may serve as a reliable signal of individual quality. Michael et

al. (2018) showed that color of the gular pouch in Brown Boobies in México was

related to foraging range and location, with individuals in poor body condition

constrained to low-cost, short-distance foraging trips closer to shore, where

they were unable to obtain the pelagic diet necessary for production of the

carotenoid-rich gular pouch ornament important in mate attraction.

Cumulatively, this research indicates that the morphological differences

between S. l. brewsteri and S. l. plotus act as an isolating

mechanism that inhibits interbreeding.

The morphological

and genetic differences between S. l.

brewsteri and other forms of the Brown Booby meet the standards for species

recognition under the typological (or morphological) and phylogenetic species

concepts, respectively (Mayr 2000, Wheeler 2000). The behavioral evidence

described in this study, increasing sympatry with primarily assortative mating

and rare interbreeding, meets the standards of the biological species concept

(Mayr 2000). Cumulatively, all three forms of evidence suggest that it would be

appropriate to consider Brewster’s Booby as a separate species again.

Occasional hybridization between S. l. brewsteri and S. l. plotus and the presence of some individuals of intermediate

appearance do not constitute evidence that they are conspecific. Similar

situations exist in two other pairs of booby species, specifically Blue-footed

Booby (S. nebouxii) and Peruvian

Booby (S. variegata), and Masked

Booby (S. dactylatra) and Nazca Booby

(S. granti). Blue-footed and Peruvian

boobies are largely allopatric, but breeding colonies occur together on two

islands off Peru, where mating is primarily assortative, with few instances of

hybridization, resulting in genetic differentiation and only limited introgression

(Figueroa 2004, Figueroa and Stucchi 2008, Taylor et al. 2012). Nazca Booby was

considered a subspecies of Masked Booby but was split into a separate species

based on morphological differences and assortative mating (Pitman and Jehl

1998, AOU 2000), which subsequently was supported by evidence of genetic

differentiation (Friesen et al. 2002).

Part B. English name:

For the English common name, according to NACC

guidelines for English names, when a split restores species status and a

previously existing English name exists, that name would be resurrected. In

this case the name would have been Brewster’s Booby. However, given the recent

decision by AOS to change all eponymous common bird names, the name Brewster’s

Booby is no longer an option. Below I have listed several possible alternative

English common names, grouped by whether they are geographical or descriptive of

the bird. I have offered some discussion of each name, including the pluses and

minuses. My personal favorite is Cocos Booby and I recommend that as the new

English common name for. S. brewsteri.

GEOGRAPHIC NAMES

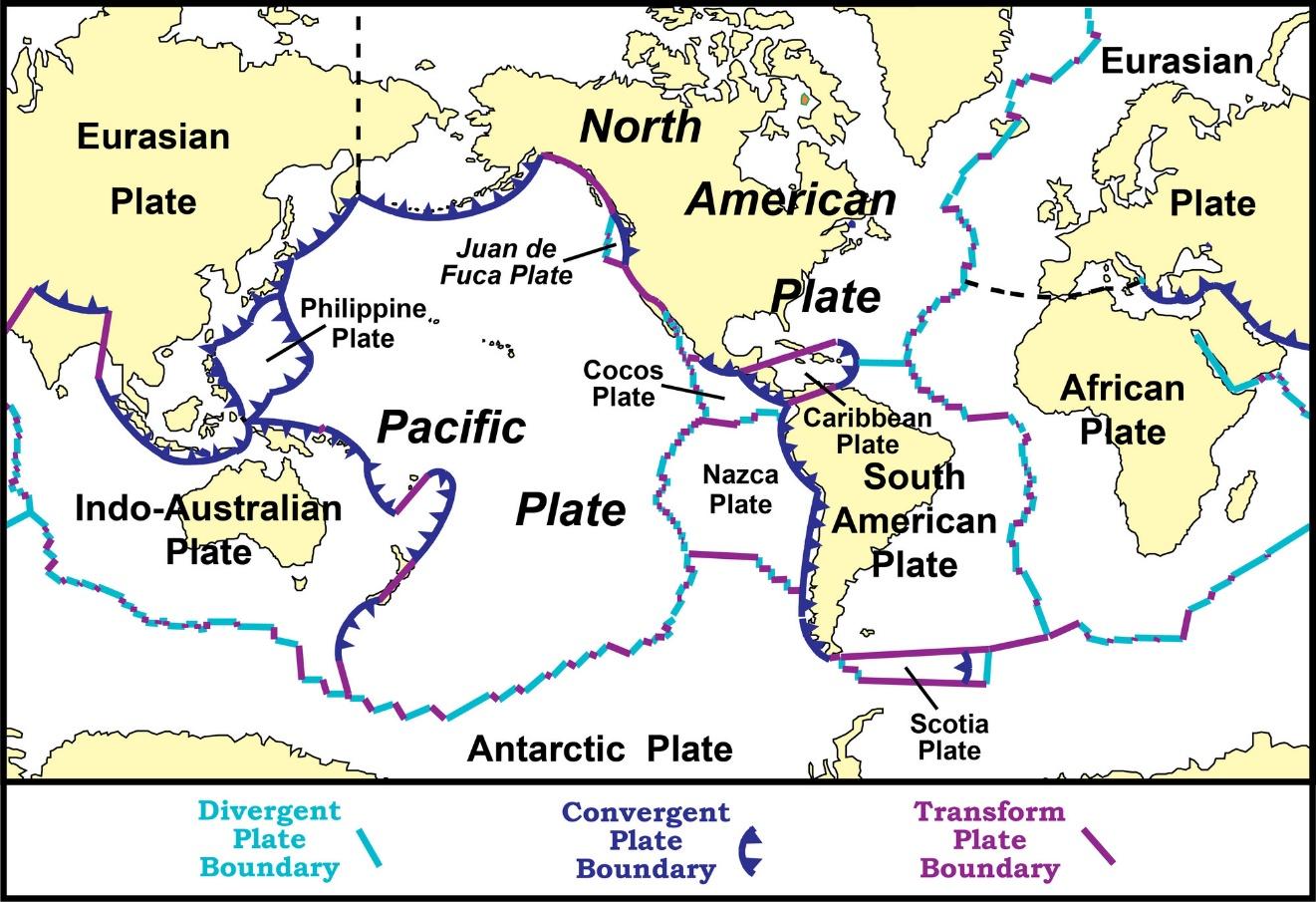

Cocos Booby. The rationale for this name is similar to that

of the Nazca Booby, which is named for a tectonic plate in the earth’s crust

that contains part of the range of that species. The Cocos Plate is located in

the eastern Pacific and is adjacent to and north of the Nazca Plate. The Cocos

Plate extends off the west coast of the Americas from Panama north to the

Mexican state of Jalisco (Figure 1). The volcanoes and earthquakes in western

Mexico and Central America are fueled by plate convergence and subduction of

the Cocos Plate under the North American and Caribbean plates. The Cocos Plate

is named for Cocos Island, which rides upon the plate and is the only part of

the plate above sea level. Cocos Island is an important nesting site for S. brewsteri, although the colonies

there are not among the largest of the species. One downside to this name is

that the Cocos Plate encompasses only a small portion of the geographic range

of S. brewsteri, although it contains

a larger proportion of the range than the Nazca Plate contains of the Nazca

Booby range. The parallel naming of Nazca Booby and Cocos Booby would provide a

logical, geographical rationale for these two species that overlap considerably

in range.

Mexican Booby. The name Mexican Booby would recognize that

much of the range of S. brewsteri

occurs in Mexico and Mexican Waters and that the type specimens were collected

in Mexico. Two drawbacks to this name are that 1) two subspecies that would be

included with S. brewsteri (S. b. nesiotes and S. b. etesiaca) are not found in Mexico, and 2) increasingly less

of the range of S. brewsteri will be

in Mexico if the current range expansion continues across the Pacific. These

same drawbacks also pertain to the name Cocos Booby. The name Mexican Booby

would provide historical context for the likely origin for many of these

dispersing birds.

Figure 1. Map of the earth’s tectonic plates, showing the

location of the Cocos Plate. From National Park Service: https://www.nps.gov/subjects/geology/plate-tectonics-evidence-of-plate-motions.htm

Tropical Eastern Pacific Booby. The Tropical

Eastern Pacific is a name applied to one of twelve marine realms that cover the

coastal waters and continental shelves of

the world's oceans as part of a global classification system called Marine

Ecoregions of the World (MEOW), which was devised by an international team,

including conservation organizations, academic institutions and

intergovernmental organizations (Spalding et al. 2007). It extends along the

Pacific Coast of the Americas, from the

southern tip of the Baja California Peninsula

in the north to northern Peru in the

south. The range of S. brewsteri

largely coincides with this geographic unit, though the species range does

extend farther to the north and south. Among geographic names this would be the

most geographically appropriate because it coincides most the with range of the

species. The main downside to this name is that it is long and cumbersome,

consisting of four words.

DESCRIPTIVE NAMES

White-headed Booby. The name White-headed Booby

is based on the most distinctive character of the species, the white head of

males, which was the character that seems to have contributed most to its

description as a separate species. However, this name has two significant drawbacks

that in my opinion disqualify it: 1) it would pertain only to males of the brewsteri and nesiotes forms, and not to males of etesiaca; and 2) it would not pertain to females of any form, and

thus would perpetuate the neglect of female appearance that has occurred

already.

Pale-headed Booby. Pale-headed Booby would be

preferable to White-headed Booby because it would apply to females and males of

all forms that would be included in S.

brewsteri. The main downside is that it seems a little bland.

Recommendation:

I recommend that S. l. brewsteri be split from other forms of the Brown Booby into a

separate species. This split has been mentioned previously (Schreiber and

Norton 2020), and the additional evidence described in this proposal

strengthens the rationale for the split. The scientific name for the re-split

species would revert to S. brewsteri,

as it was originally described by Goss (1888). Sula brewsteri should include all pale-headed subspecies that breed

in the eastern Pacific, including nesiotes

and etesiaca recognized by some

authors (Schreiber and Norton 2020). If subspecific status continues to be

recognized for these forms, they would become S. brewsteri nesiotes and S.

brewsteri etesiaca, respectively.

Although etesiaca males have a

pale, not white, head, etesiaca

females are similar to females in other forms of brewsteri, and genetically etesiaca

clearly grouped with other populations in the eastern Pacific (Steeves et al.

2003, Morris-Pocock et al. 2010). No changes are needed in taxonomic status or

nomenclature of the other Brown Booby subspecies, which are more similar to

each other morphologically and genetically (Morris-Pocock et al. 2011). Thus, S. l. plotus and S. l. leucogaster would remain subspecies of the Brown Booby.

For the English name, I recommend Cocos Booby,

for the reasons discussed above.

Note from Remsen on voting on Part B. A YES vote is for Cocos Booby,

the recommendation of the proposal and the unanimous choice of NACC, and a NO

is for some other name; please indicate if that is Brewster’s Booby, the

traditional name of the taxon, or some novel name.

Literature Cited:

Avise, J. C., W. S.

Nelson, B. W. Bowen, and D. Walker. 2000. Phylogeography of colonially nesting

seabirds, with special reference to global matrilineal patterns in the sooty

tern (Sterna fuscata). Molecular

Ecology 9:1783-1792.

Del Hoyo, J., A. Elliott, and J. Sargatal. 1992. Handbook of birds of

the world. Volume 1. Barcelona: Lynx Editions.

Figueroa, J. 2004. First record of breeding by the Nazca Booby Sula granti on Lobos de Afuera Islands,

Peru. Marine Ornithology 32:117-118.

Figueroa, J., and M.

Stucchi. 2008. Possible hybridization between the Peruvian Booby Sula variegata and the Blue-footed Booby

S. nebouxii in Lobos de Afuera

Islands, Peru. Marine Ornithology 36:75-76.

Friesen, V. L., D. J. Anderson, T. E. Steeves, H. Jones, and E. A.

Schreiber. 2002. Molecular support for species status of the Nazca Booby (Sula granti). Auk 119:820–826.

Goss, N. S. 1888. New

and rare birds found breeding on the San Pedro Martir

Isle. Auk 5:240-244.

Heller, E. and Snodgrass, R.E. 1901. Descriptions of two new species and

three new subspecies of birds from the Eastern Pacific, collected by the

Hopkins-Stanford expedition to the Galapagos Islands. Condor:74-77.

Kohno, H., and A. Mizutani. 2011. The first

record of Brewster’s Brown Booby Sula

leucogaster brewsteri for Japan. J. Yamashina Institute for Ornithology

42:147‒153.

Kohno, H., and A. Mizutani. 2015. First record

of breeding behaviour of Brewster’s Brown Booby Sula leucogaster brewsteri in Japan. J. Yamashina

Institute for Ornithology 46:108-118.

López-Rull, I., N. Lifshitz, C. M. Garcia, J.

A. Graves, and R. Torres. 2016. Females of a polymorphic seabird dislike

foreign-looking males. Animal Behaviour 113:31-38.

Michael, N.P., R. Torres, A. J. Welch, J. Adams, M. E. Bonillas-Monge, J. Felis, L. Lopez-Marquez, A.

Martínez-Flores, and A. E. Wiley. 2018. Carotenoid-based skin ornaments reflect

foraging propensity in a seabird, Sula

leucogaster. Biology letters 14:20180398.

Montoya, B., C. Flores, and R. Torres. 2018. Repeatability of a dynamic

sexual trait: Skin color variation in the Brown Booby (Sula leucogaster). The Auk: Ornithological Advances 135:622-636.

Morris-Pocock, J. A., D. J. Anderson, and V. L. Friesen. 2011.

Mechanisms of global diversification in the Brown Booby (Sula leucogaster) revealed by uniting statistical phylogeographic

and multilocus phylogenetic methods. Molecular Ecology 20:2835‒2850.

Morris-Pocock, J. A., T. E. Steeves, F. A. Estela, D. J. Anderson, and

V. L. Friesen. 2010. Comparative phylogeography of Brown (Sula leucogaster) and Red-footed Boobies (S. sula): the influence of physical barriers and habitat preference

on gene flow in pelagic seabirds. Molecular Phylogenetic and Evolution

54:883‒896.

Nelson, J. B. 1978. The Sulidae. Oxford University Press, London.

Pitman, R. L., and L. T. Ballance. 2002.

The changing status of marine birds breeding at San Benedicto

Island, Mexico. Wilson Bulletin 114: 11-19.

Pitman, R., and J. Jehl. 1998. Geographic variation and reassessment of

species limits in the “Masked” boobies of the eastern Pacific Ocean. Wilson

Bulletin 110:155–170.

Rauzon, M. J., D. Boyle, W. T. Everett, and J. Gilardi.

2008. The status of birds of Wake Atoll.

Atoll Research Bulletin 561:1-41.

Schreiber, E. A., and R. L. Norton. 2020. Brown Booby (Sula leucogaster), version 1.0 In Birds

of the World (S.M. Billerman, Ed.). Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, NY,

USA: https://doi.org/10.2173/bow.brnboo.01

Spalding, M.D., H. E. Fox, G.R. Allen, N. Davidson, et al. 2007. Marine

Ecoregions of the World: A Bioregionalization of Coastal and Shelf Areas.

Bioscience 57(7):573–583.

Steeves, T. E, D. J. Anderson, H. Mcnally, M.

H. Kim, and V. L. Friesen. 2003. Phylogeography of Sula: the role of physical barriers to gene flow in the

diversification of tropical seabirds. J. Avian Biology 34:217-223.

Steeves, T. E, D. J. Anderson, and V. L. Friesen. 2005. A role for

nonphysical barriers to gene flow in the diversification of a highly vagile

seabird, the Masked Booby (Sula

dactylatra). Molecular Ecology 14:3877-3887.

Taylor, S. A., D. J. Anderson, C. B. Zavalaga,

and V. L. Friesen. 2012. Evidence for strong assortative mating, limited gene

flow, and strong differentiation across the Blue‐footed/Peruvian

booby hybrid zone in northern Peru. Journal of Avian Biology 43:311-324.

VanderWerf, E. A.

2018a. Geographic variation in the Brown Booby. Field identification of males

and females by subspecies. Birding 50:48-54.

VanderWerf, E. A., B. L. Becker, J. Eijzenga,

and H. Eijzenga. 2008. Nazca Booby Sula granti and Brewster’s Brown Booby Sula leucogaster brewsteri in the

Hawaiian Islands and Johnston and Palmyra Atolls. Marine Ornithology 36:67–71.

VanderWerf, E. A., M.

Frye, J. Gilardi, J. Penniman, M. Rauzon,

H. D. Pratt, R. S. Steffy, and J. Plissner. 2023.

Range expansion, pairing patterns, and taxonomic status of Brewster’s Booby Sula leucogaster brewsteri. Pacific

Science 77:1-12.

Wetmore, A. 1939.

Birds from Clipperton Island collected on the presidential cruise of 1938.

Smithsonian Miscellaneous Collections 98(22):1-6.

Wetmore, A.,

Friedmann, H., Lincoln, F.C., Miller, A.H., Peters, J.L., van Rossem, A.J., Van

Tyne, J., and Zimmer, J.T. 1944. Nineteenth supplement to the American

Ornithologists’ Union Check-list of North American birds. Auk 61:441-464.

Wheeler, Q. D. 2000.

The phylogenetic species concept (sensu

Wheeler and Platnick). Pp. 55-60 in Species Concepts

and Phylogenetic Theory: a Debate (Q.D. Wheeler and

R. Meier, eds.).

Columbia University Press, New York.

Eric A. VanderWerf,

April 2024

Additional notes on Part B – English name. When Remsen told VanderWerf

that SACC was not bound by the edict of the AOS Council on removing all

eponyms, VanderWerf responded by noting that he was not opposed to eponyms but

still preferred Cocos Booby for the following reasons: “I

prefer Cocos Booby for 3 reasons: 1) I like geographic names, and

this offers a nice parallel with Nazca Booby; 2) if the NACC also adopts the

split, then there would be a chance that the same English name, Cocos Booby,

would be recognized by both groups. Having different common names would be

confusing; and 3) the Spanish name, which has not been discussed and I don’t

know where/how/when that would happen, presumably would be Bobo Cocos, which

has a nice ring to it.”

Comments

from Remsen:

“Part

A: YES. The lack of non-assortative mating is striking especially because

reproductive isolating mechanisms in birds tend to be weakest when range

expansions bring taxa together that have had little previous contact. Also, note that the phenotypic differences

between Sula dactylatra and Sula granti roughly comparable to

those between brewsteri and leucogaster. Note also that there was no evidence for the

Peters-Wetmore lump of the two species.

The 4th edition of the AOU Check-list (1931) treated it as a

separate species, Brewster’s Booby (S. brewsteri) from Sula l.

leucogaster (White-bellied Booby), and the broadly defined species

treatment then appeared in the 5th edition (1957) based solely on

Peters’ and Wetmore’s treatment.

“Part

B: NO. I think Cocos is a much better name than any of the others in the

proposal for the biogeographic rationale outlined therein. Nevertheless, the title of VanderWerf et

al.’s paper makes it clear why Brewster’s is the better name in that that is

the name that seabird people use for the distinctive taxa of the eastern

Pacific. What better evidence do we need

than this that the name has about 130+ years of formal and informal association

with the eastern Pacific taxa? See also

the title of VanderWerf et al. (2008) above.

See also any of the 20+ papers, most of them published in The Auk,

that used “Brewster’s Booby”, as revealed by Google Scholar. Google search on “Brewster’s Booby” produces

934 hits. Brewster’s Booby was the name

used by the AOU (1931), where treated as a separate species. Hellmayr and Conover (1948) also used

Brewster’s Booby for S. l. brewsteri.

More recently, Howell and Zufelt (Oceanic Birds of the World, 2019,

Princeton Univ. Press) used “Brewster’s Brown Booby” for S. l. brewsteri.

“Although Goss, who also described brewsteri,

made no attempt to justify that name and in fact did not make it clear that brewsteri

presumably honored “the” Brewster of ornithology, i.e. William Brewster. That was because it was so obvious that

William Brewster’s contributions to the avifauna of Baja California (e.g.,

“Birds of the Cape region of Lower California”, 1902, Bull. Museum Comp.

Zoology, 241 pp., and many additional papers, based on existing collections and

collections that he commissioned, but not on his own fieldwork) were so

important that no explanation was needed.

“William Brewster’s contributions to

ornithology go far beyond Baja California.

He was one of three founding members of the American Ornithological

Society itself (1873), and served as its president for three years. The AOS’s Brewster Medal is one of the three

highest awards it gives for research.

Brewster was a Fellow of the American Academy for Advancement of Science

(AAAS). He was the founder and a president of the Nuttall Ornithological Club,

the oldest ornithological society in the Western Hemisphere. He was the first president of Mass Audubon

from 1896 to 1913, and the major goal of that society was to restrict the

killing of wild birds and was a force behind passage of the Lacey Act of 1900

(which prohibits interstate commerce in wild birds killed illegally). Brewster was curator of birds at Harvard’s

Museum of Comparative Zoology from 1885 until his death in 1919. Henshaw’s 23 page memorial to Brewster in the Auk in 1920 outlines his many

additional contributions and personal attributes; Henshaw made it clear that Brewster was what

we would call a “good guy” nowadays:

‘He

was charitably disposed to all, and inclined to judge the delinquent leniently

and with forbearance. He never spoke ill of any man. He was generously

inclined, and, within his means, gave freely to those less fortunate than

himself, though of his beneficence he said nothing, preferring that it should remain unknown.

‘He

was absolutely truthful, habitually refrained from all exaggeration, and

falsehood and evasion were foreign to his nature. As he was sincere and

truthful, so was he honorable and pure minded, and his conversation reflected

the thoughts and imaginings of a pure soul.’

“Some tidbits gleaned from these and other

sources: All three of his siblings died in childhood; their early deaths

evidently inspired the poem The Open Window, by Henry Wadsworth

Longfellow, one of the Brewster family’s neighbors. Brewster had some sort of vision problem as a

child, but that seems to have passed as he became an adult. His extensive field notes have been digitized

and are online, and browsing through these, it is clear that Brewster was not

only a keen observer of birds but really loved them. Actually watching birds and describing their

behavior was his passion, and in this way seemed ahead of his time despite what

must have been primitive optics. Perhaps

in compensation, he had a reputation for extremely sharp hearing and ability to

identify birds at a distance by voice to the extent that Henshaw considered him

supremely talented:

‘His hearing was

extraordinarily acute, and his ability to recognize the notes of birds at a

distance and amid other and confusing sounds was little less than marvelous,

and far exceeded that of any one I ever knew.’

“His 38 years of fieldwork at Lake Umbagog, on the Maine-New Hampshire border, produced some

legendary observations, often from his canoe, to the point that Robert Stymiest published excerpts as a paper in the Bird Observer in 2004. At Lake Umbagog, he

made the first detailed observations

of the nesting behavior of the Philadelphia Vireo, as just one of his

many contributions. He was also one of

many famous naturalists who made extensive observations in the Concord,

Massachusetts, and kept copious field notes on his experiences there; in fact,

in 1937, a 300 page book of

selections from his Concord journals was published.

Brewster was also interested in bird migration, and actually spent 6

weeks in Fall 1885 at a lighthouse in the Bay of Fundy do study the behavior of

migrating birds. The paper he published

on these observations was a classic of the era.

“I herein take the opportunity to make some

positive remarks on eponymous English names.

Brewster’s case, in my opinion, provides a strong example of the value

of eponyms. Yes, many of these founders

of American ornithology are memorialized in other ways, including scientific

names. However, most birders and even

many professional ornithologists have a weak knowledge of scientific names, and

even fewer are inclined to delve into the general history of ornithology in

North America on their own. An English

name, however, gets the attention of every bird person who uses it. Most will never take the time to read about

these people, but those who do will hopefully be inspired and will be reminded

that we got where we are today in our understanding of birds through the work

of those who preceded us. Knowing that we

humans are instinctively interested in stories about other humans, I doubt that

I am the only one inspired by the stories of people like Brewster. Some of you may know why I have a special admiration

for Brewster, but I hope all of you will appreciate this accomplishments and

the reverence in which he was held by his peers. Contrast the window into ornithology opened

by “Brewster’s Booby” compared to the value of a name like “Brown Booby,” its

sister species. Yes, Brown Booby is an

excellent descriptive name. It is indeed

a brown booby, brownest of the genus.

But that’s where the value ends.

There is no depth, no cachet, no inspiration. In my opinion, I think that having a tiny

percentage of English names that honor contributors to ornithology acknowledges

that we did not get here on our own and provides potential inspiration for

others to contribute to ornithology and especially in a case like Brewster to

appreciate birds more deeply.

“Additional

points: one problem with Cocos is that the name is clearly associated with

three endemics of Cocos Island (Cocos Cuckoo, Cocos Flycatcher, Cocos Finch)

and thus the natural implication of the name “Cocos Booby” is that it is

another island endemic. Few people are

aware of the name Cocos Plate, and so confusion will be inevitable. By the way, there is no need to discuss

adding group names in this case, e.g. “Cocos Brown-Booby” etc., because our

guidelines indicate that there is no need for that if two species previously

split, then lumped, and then re-split --- the original species treatment used

Brewster’s Booby for S. brewsteri (and White-bellied Booby for S.

leucogaster). Using White-bellied

Booby for narrowly defined S. leucogaster also should be discussed, as

recommended in our guidelines on English names because it calls attention to

the species split and restores a historical name used in much literature prior

to 1957.”

Comments from Don Roberson (voting for Claramunt on

Part B): YES on Cocos Booby.

Although "Brewster's Booby" would have been okay with me, some people

disfavor eponymous common names, so a different English name is fine at this

point in time. The genus Sula

currently has a nice set of English names: Red-footed, Blue-footed, Brown,

Peruvian, Masked, and Nazca. [in the Sulidae, only the monotypic genus Papasula

has an eponymous name, but it resides far from the New World.]

“Traditionally, the long-standing set of

the five basic Sula boobies were Red-footed, Blue-footed, Brown,

Peruvian, and Masked. All are short, distinctive, and memorable -- 4 are based

on plumage and/or soft-parts color, and one is named for the Peruvian Current

where it occurs. Red-footed and Blue-footed are surely among the "really

good English names" for those species. Brown and Masked are accurate and

serviceable. Then came the first split in Sula, and I was delighted when

the authors of the taxonomic paper (Pitman & Jehl 1998) concluded with this

line: "As a common name for Sula granti we propose Nazca

Booby, which recognizes that the current breeding range and probably

evolutionary history of this species is closely associated with the Nazca

Crustal Plate."

“This was a great English name -- short,

very memorable, reasonable accurate, and innovative. In 1989, when I spent 4

months in the eastern tropical Pacific on a NOAA ship, with Bob Pitman on a

sister ship on that cruise, Bob asked me to take notes on the juvenal

"Masked" Boobies when we went through the Galapagos, which he used in

writing his 1998 paper [later, I wrote a paper on ID issues in Masked &

Nazca Boobies.] On that same cruise, we had the good fortune to visit Isla del

Coco [Cocos Island, off Costa Rica] and even land on the island. My notes also

mention a "breeding colony on Nuez I., where

Gary Fredrichsen saw fledglings" of brewsteri

Brown Booby while I was on Cocos itself (Nuez is a

tiny islet in Chatham Bay; we also scoped it with the ship's Big Eyes).

“Now, we have an opportunity to give S.

brewsteri another excellent English name: Cocos Booby. It parallels the

name Nazca Booby nicely. Neither name includes all the breeding range of the Sula

involved, let alone its at-sea distribution, but

Cocos is a core breeding location, well represents core at-sea range, and does

so better than the Nazca Plate did for Nazca Booby. It is really a fine choice:

short, very memorable, reasonable accurate, and innovative in parallel with

Nazca. While it is useful to name local resident landbird endemics for the

island on which they occur (e.g., Cocos Finch), it is also appropriate to name

a seabird after the tectonic plate which covers a good portion of both its

breeding and its pelagic range, postulating, as did Pitman & Jehl, that it

is likely that the "evolutionary history of this species is closely

associated with the Cocos Crustal Plate."

“None of the other options are as

attractive. "White-headed" and "Pale-headed" are rather

boring, do not accurately describe all subspecies, and focus only on adult male

plumages but would not be accurate for well over half of the birds encountered

(females, sub-adults, and juvs). "Tropical Eastern Pacific Booby" is

a jaw-breaker, not significantly more accurate, and would break the string of

having the names of all Sula boobies be short, distinctive, and punchy.

Finally, "Mexican Booby" is misleading is multiple ways -- Mexico

(including the western coast of Mexico) has multiple species of boobies, but

more importantly, the eastern coast of Mexico will have a Brown Booby from the

Gulf that is not brewsteri, so a "Mexican Booby" would not

even include the Caribbean coast, with its entirely different type of

"Brown Booby", adding to confusion.

“VanderWerf et al. (2023) did point out

that there are four major lineages in Brown Booby: Caribbean, central Atlantic,

Indo-central Pacific, and eastern Pacific. Some have suggested that all might

be elevated to species level, and that in doing so, a hyphenated English name

-- Brown-Booby -- should be preceded by a modifier to create, say, Caribbean

Brown-Booby, Atlantic Brown-Booby etc. SACC has adopted this sort of scheme

multiple times, but generally in complex situations (e.g., the Trogonidae,

Thamnophilidae). The Sula boobies are currently just 7 species (with brewsteri)

and only 10 species if the other 3 Brown Booby lineages were to be split, and

even the entire Sulidae would be just 14 species. I don't think we need

hyphenated English names is this relatively small group of Sulids, and to do so

would create long names which are neither short, memorable, or punchy. But even

if later taxonomic changes might be made, Cocos Booby or "Cocos

Brown-Booby" would still be the best choice, in my opinion, for the

eastern Pacific taxa.

“Citation: Pitman & Jehl (1998)

Geographic variation and reassessment of species limits in the "Masked

" boobies of the eastern Pacific Ocean. Wilson Bull 110: 155-170.”

Comments from Claramunt (Part A): “A. YES. The combination of morphological, genetic and behavioral

information provides compelling evidence for the species status of E Pacific

taxa.”

Comments from Stiles: “A. YES to

Split Sula brewsteri from S. leucogaster. B. NO. I definitely

prefer Brewster’s as the E-name, given my strong objection to AOS’s decision to

abolish all eponyms, thus ignoring nomenclatural history and Brewster’s

significant contributions to the development of American ornithology.”

Comments from Robbins:

“A. YES for recognizing Sula brewsteri as a species given that this

taxon appears to be consistent with species-level treatment of other taxa in Sula.”

Comments from Areta: “A.

YES,

the evidence is more fitting with species status for brewsteri, although I would not be averse to having more genetic

information on the distinction and effect of gene flow between the syntopic

birds.”

Comments

from David Ainley (voting for Del-Rio): B. NO on Cocos

Booby and YES on something else. Cocos too geographically restrictive for the

species. Brewster's Brown Booby would be fine with me, and kind of how I have

always considered it. For what it's worth, though, if given the choice, I'd go

with Eastern Pacific BB (for S. brewsteri) should the other BBs become

known as Indo-Pacific BB and Atlantic BB. That's more in line with how Gannets

are named.”

Comments from Bonaccorso: “A. YES. All the evidence

supports the idea that Sula

brewsteri is a good

species, morphologically diagnosable and reproductively isolated.”

Comments from Jaramillo:

“A – YES to the split of

Brown Booby. Apart from the biology of sympatry and avoidance of hybridization

with is key here. I will also point out, and this is in the proposal that for

years it has been stated that the females are unidentifiable. But VanderWerf et

al. have shown that they are actually identifiable -- it is just more difficult. We have started

using these criteria in the field, and they seems to work.

“B – YES to Cocos Booby. Memorable, easy to spell, and a name that

is similar in etymology to Nazca. Cocos means a lot of things, including

coconuts in most Spanish places, but it is slang for testicles in Chile. Most

words are slang for testicles in Chile, so I would not be concerned, and this

is the English Name, not the Spanish Name. But I wanted to mention that. It

also can mean your brain/mind in slang.”

Comments

from Debra Shearwater (voting for Bonaccorso): “YES to

Cocos would be my vote. Memorable, easy to spell, short. It bookends with Nazca

Booby.”

Comments

from Lane:

“YES on both. It seems NACC has already accepted this split and the English

name “Cocos Booby.” The assortative nesting certainly suggests that the S.

brewsteri is acting as a good species where it overlaps with other

populations of S. leucogaster in the central and eastern Pacific. The

English name “Cocos,” whereas calling to mind a single island to me, follows

the logic of “Nazca Booby” and thus makes sense after some thought.”

Comments

from Scott Terrill: B:”NO to Cocos Booby. In voting no

on B, I agree with all of the rationale provided, in detail, by Remsen,

including but not limited to: (1) The extensive historical precedence for

the name "Brewster's" Booby with eastern Pacific taxa; (2) Brewster's

immense early contributions to ornithology and, as Remsen put it; (3)

"Henshaw made it clear that Brewster was what we would call a 'good guy'

nowadays."

Additional

comments from Stiles:

“Here, I have a very strong opinion that “Cocos Booby” is a singularly

inappropriate name for Sula brewsteri, and that the reasons for NACC’s

adoption of it are most ill-founded. To begin with, geography. The majority and

best-known part of the Cocos plate constitutes the floor of the Caribbean,

which immediately causes confusion by implying that brewsteri is a

Caribbean bird. By contrast, Cocos I. is near the western extreme of this

plate, effectively an outlier as well as constituting only a minute fraction of

the distribution of brewsteri. Regarding the presence of this species on

Cocos I., my experience suggests that it is also an insignificant part of this

distribution. I spent a week in 1975 on and around Cocos and, mindful of a

previous unconfirmed record of its breeding there on an outlying islet at about

the same time of year, I made a special effort during two slow circuits of the

island to observe this species on these islets as well as the many cliffs of

the island itself – and never saw it there, or in the surrounding waters. My

conclusion was that if brewsteri breeds (or even occurs) there, it must

be in small numbers and probably not regularly. All of this puts Cocos Booby in

the same league for aptness in distributional terms as Tennessee Warbler or

Philadelphia Vireo. The analogy between Cocos Booby and Nazca Booby (for S.

granti), while sounding cute, is also flawed (simply compare the data for

the distribution and status of brewsteri above with that of S. granti

with respect to the Nazca plate, the distribution of which lies entirely

offshore in the Pacific, the rest being subducted under the South American

continent. The major and best-studied breeding colony of granti is

centered on this plate and its seaward distribution is also centered on and

around it, making Nazca Booby a most appropriate name. In fact, the seaward

distribution of brewsteri also includes the Nazca plate (to a greater

extent than its occurrence on the Cocos plate: it could even be called the

“Lesser Nazca Booby” more appropriately). Finally, regarding English names,

Brewster’s Booby has a considerable track record among the seabird fraternity,

which after all has a better appreciation of its global distribution (than at

least, the NACC, which due to its recently-acquired obligatory eschewing of

eponyms, must ignore “Brewster´s Booby”. I see no reason why SACC should follow

suit and condone, much less honor this practice and strongly suggest that

members of the SACC approving “Cocos Booby” should reconsider their votes and

give more serious consideration to “Brewster´s Booby” as a better name.

Following the leader out of “loyalty” to the NACC seems unwise if the “leader”

itself, makes what from any knowledgeable viewpoint is an unwise decision.”

Additional

comments from Remsen:

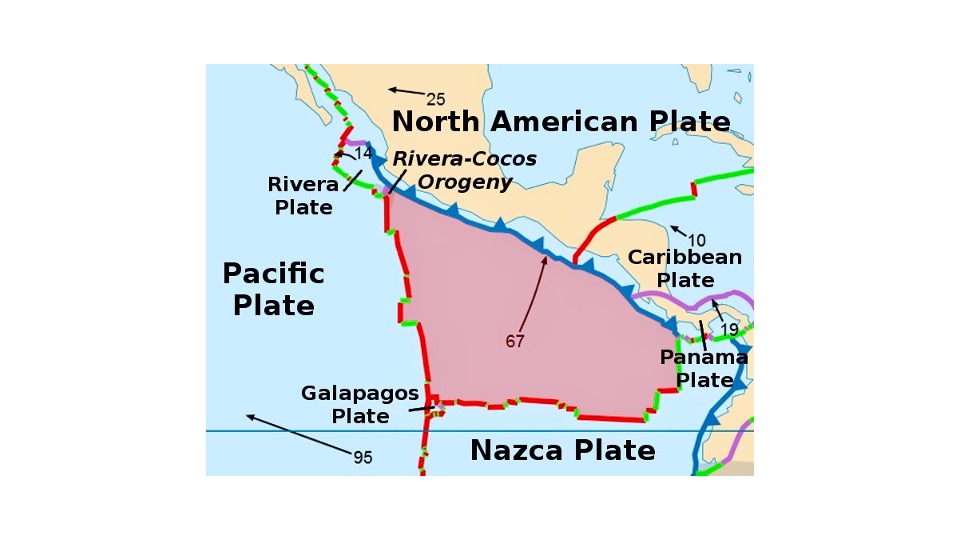

The proposal maps the Cocos Plate, and I decided to elaborate by mapping

brewsteri breeding distribution on the plate in a crude way.

Here’s

a more detailed map of the Cocos Plate from Wikipedia:

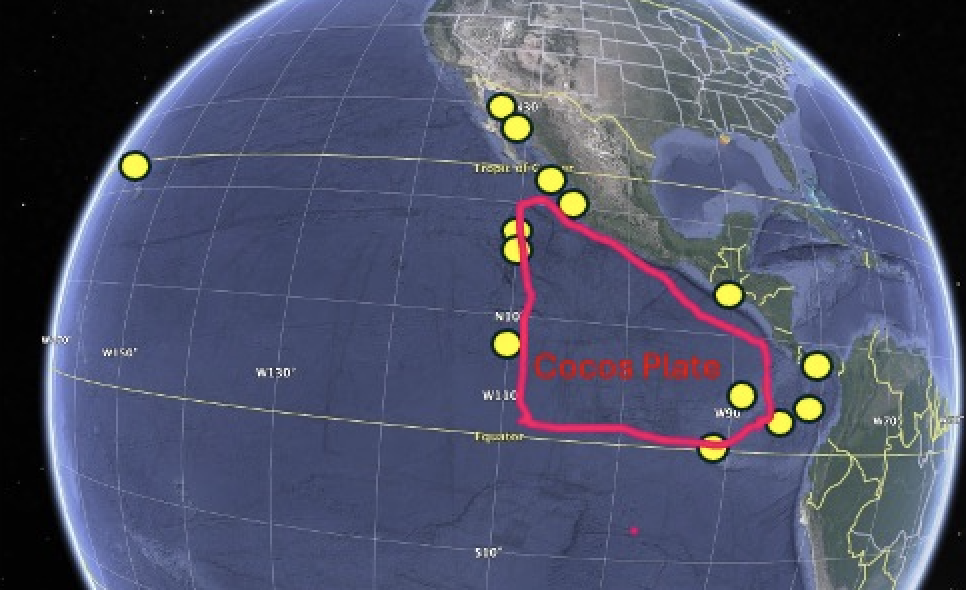

And

here’s my first attempt at crudely mapping by eye the breeding distribution of brewsteri

from some of its most prominent breeding locations as given in Birds of World

and elsewhere (yellow circles). I will

likely refine this to make it more accurate, and additions/corrections are

welcome. But the bottom line, barring

gross inaccuracy, is that for geographic name, Cocos Booby is pretty good in

that it looks like the tectonic activity of the plate produced many of the

islands on which the species breeds, and even some of the islands not on the

plate were formed by interactions between the plate and other ridges. Much of the distribution in Mexico lies north

of the plate and of course the range expansion to Hawaii has added territory

far from the plate, but nonetheless for a geographic name that doesn’t refer to

a single island or isolated mountain range, it’s not bad at all in my

opinion. The species occurs mainly along

the margins of the plate, not the deep ocean within the plate.

Comments

from Zimmer:

“YES to Part A. The clincher for me is

that both brewsteri and plotus are expanding their ranges,

increasingly coming into contact, and are still, for the most part,

assortatively mating in contact zones.

The suggested mechanism of mate choice based upon gular pouch coloration

as an indicator of fitness, and reported increased female aggression towards

“foreign” males closer to contact zones, is pretty inspired in my opinion. The situation also draws some obvious

parallels with the Blue-footed versus Peruvian boobies and the Masked versus

Nazca boobies, as noted in the Proposal.

NO on Part B. I too, prefer

reverting to the widely recognized and historically used “Brewster’s Booby” for

all of the reasons spelled out by Van and Gary.

I don’t have any particular objection to “Cocos Booby” for brewsteri,

even if it means we would be combining sexualized slang for testicles and

breasts from two different language systems in the same bird name (!) – as

others have noted, it is pithy and memorable, and has at least some precedence

in the name already given to S. granti.

However, the rationale for discarding a long-standing name with

historical traction, that honors one of the giants of ornithology, and someone

who seemingly meets the character test of even modern generations, simply to

follow what I consider to be the misguided dictates of the AOS, just doesn’t

sit well with me. Don Roberson gives a

good synopsis of why some of the other proposed names (“Mexican Booby”,

“White-headed Booby”, “Pale-headed Booby”) are not good choices, and I agree

with his reasoning on each of those. So,

I won’t fight “Cocos Booby” if that’s the way the SACC vote goes down, but I

would prefer “Brewster’s Booby” for brewsteri.”