Proposal (997) to South

American Classification Committee

Treat Deconychura

longicauda (Long-tailed Woodcreeper) as three species

Note:

This is one of several situations that the IOU Working Group on Avian

Checklists has asked us to review because published treatments of the species

differ, and WGAC has to pick one.

In

this case BirdLife International split Deconychura into three species,

whereas Clements/eBird, IOU, and Howard-Moore (as well as SACC) continue to

treat it in the traditional way as one species.

Here

is the BirdLife rationale, as provided by Marshall Iliff:

“Little Long-tailed

Woodcreeper [D. typica, including also subspecies darienensis

and minor; from Honduras through Central America to N. Colombia]: In

past, sometimes considered a separate species from D. longicauda

and D. pallida, and this arrangement restituted here, based on

smaller size (male wing 91–99 mm, n=9, vs respectively 106–110, n=3, and

102–111, n=4; allow 2); spots vs streaks on breast (2); chestnut

undertail-coverts (2); clearer buff-white chin and throat (1); song a long fast

series of short piping notes, starting slowly and slowing at end, hence high

number of notes (4) and very short note lengths (4) (1). Birds from NW Colombia

(Córdoba) may be intergrades between darienensis and minor. Three subspecies

recognized.

“Northern

Long-tailed Woodcreeper [D. longicauda; the Guianas and Brazil N of the

Amazon]: Usually considered conspecific with D. typica and D. pallida

(see both). Monotypic.

“Southern

Long-tailed Woodcreeper [D. pallida, including also subspecies connectens;

W and S Amazonia]: Hitherto considered conspecific with D. longicauda

and then usually also with D. typica, but differs from latter in

characters given under that species and from former in its shorter tail (in

male 92–105 mm, n=4, vs 107–109; at least 1); whitish vs strong buffish chin

and streaks on throat to breast (1); and distinctive song, a series of c. 8

flat whistles vs a series of 6–10 long upslurred whistles (both gradually

descending in pitch), hence having much shorter notes (3) with pitch of first

note much higher (3) and note shape different (ns[2]) (1). Populations in

Andean foothills of E Ecuador apparently belong to connectens, but

adjacent lowland birds may be of race pallida; in these foothills,

either connectens or an undescribed taxon sings a very different song, a

series of c. 10–14 double notes, slightly descending in pitch, suggesting a

species-rank difference; undescribed taxon, perhaps same, reported from

foothills of NE & NC Peru (2). Recent analysis of whole genus using voice,

morphology and genetics (3) proposed promotion to full species status of the

three races currently included herein, as well the undescribed taxon from

Andean foothills; however, differences appear slight, and vocal analysis based

on very small samples, some of which may be unrepresentative. Names pallida

and connectens published simultaneously; former awarded priority by

First Reviser (4). Three subspecies recognized.

Our current SACC note reads as follows:

“109. The subspecies typica was formerly (e.g., Ridgway 1911,

Cory & Hellmayr 1925) treated (with minor and Panamanian dariensis) as a separate species from Deconychura

longicauda, but Zimmer (1934) treated it as a subspecies of D. longicauda

without comment, and this was followed by Peters (1951) and subsequent

classifications. Marantz et al. (2003)

indicated that vocal differences among populations suggest that more than one

species might be involved, with the typica group possibly more closely

related to Certhiasomus stictolaema than to Amazonian longicauda group. Barbosa (2010) found vocal evidence that D.

longicauda consists of three of more species. Boesman’s (2016f) analysis of vocalizations

also supported recognizing at least three species, and this was done by del

Hoyo & Collar (2016): D. typica of primarily Middle America, D. longicauda

of the Guianan Shield, and D. pallida of Amazonia.

”

Here are LSUMNS specimens of the three proposed

species, top to bottom: typica (represented by darienensis), longicauda,

and pallida). Note that HBW/BLI

awarded something like 7 points in the Tobias et al. scheme based on phenotypic

characters such as throat color, undertail coverts color, and size (if I am

interpreting the numbers above correctly); make your own call on whether what

you see below would be sufficient for species rank. See also photos in Barbosa (2010), although

some of those did not reproduce well.

The vocal data in the BLI account come from

Boesman’s (2016) brief synopsis, one of 457 he prepared to evaluate vocal

differences in advance of del Hoyo & Collar (2016) for use in the Tobias et

al.’s point system: once a total of 7 points is achieved using various

morphological and vocal characters, a taxon is ranked as a species. The analysis of the Deconychura

referred to as “(3)” in the accounts is an unpublished MS thesis (Barbosa

2010). The reference to treatment as

separate species in the past likely refers to Cory & Hellmayr (1927), which

treated the complex as two species, D. typica and D. longicauda;

at that time no subspecies were described within longicauda and it thus

including all Amazonian populations. Of

interest is that the linear sequence of species in Deconychura in Cory

& Hellmayr implies that they did not consider them sister species (D.

stictolaema separating them), as is also implied in their discussion of

similar species in the footnotes.

This situation in an increasingly familiar one

in species limits in Neotropical birds: fragmentary and anecdotal information

strongly suggest that more than one species is involved yet no peer-reviewed

paper has been published that evaluates the evidence. The conundrum is whether to anticipate what a

formal analysis would indicate or wait for the formal analysis to appear.

In this case, we do have an unpublished formal

analysis, and so the conundrum also includes whether to treat an unpublished

analysis, albeit available online, as sufficient evidence. (It’s a solid thesis; Alex Aleixo was

Barbosa’s advisor, and John Bates and Jason Weckstein served on the committee.)

As for the Tobias et al. point system used by

BLI/HBW, none of the phenotypic characters mentioned in the quoted accounts

above is any more associated with species-level differences than with subspecies-level

differences. In the dendrocolaptids,

differences in all those features are routinely found between taxa treated as

subspecies because of vocal similarities.

So, it all boils down to vocal differences in my opinion.

Marantz et al. (2003) noted that the typica

group had once been considered a separate species, possibly more closely

related to then=Deconychura, now=Certhiasomus stictolaema. They

also outlined the strong vocal differences between the typica, pallida

and longicauda groups. At that

time the Andean foothill taxon was not well known and was thought to be D.

p. connectens.

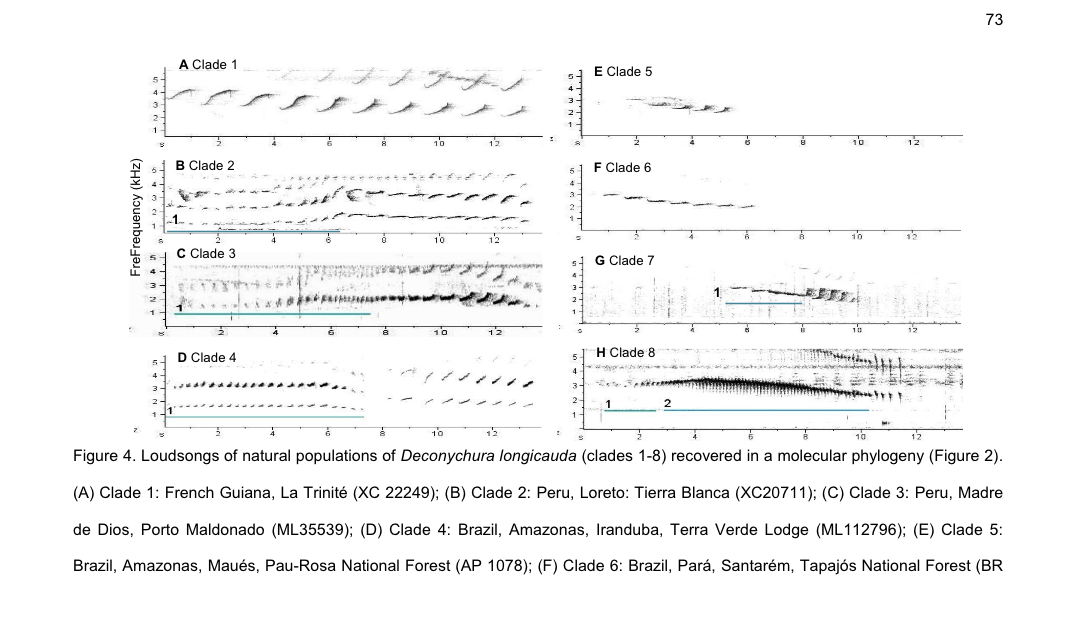

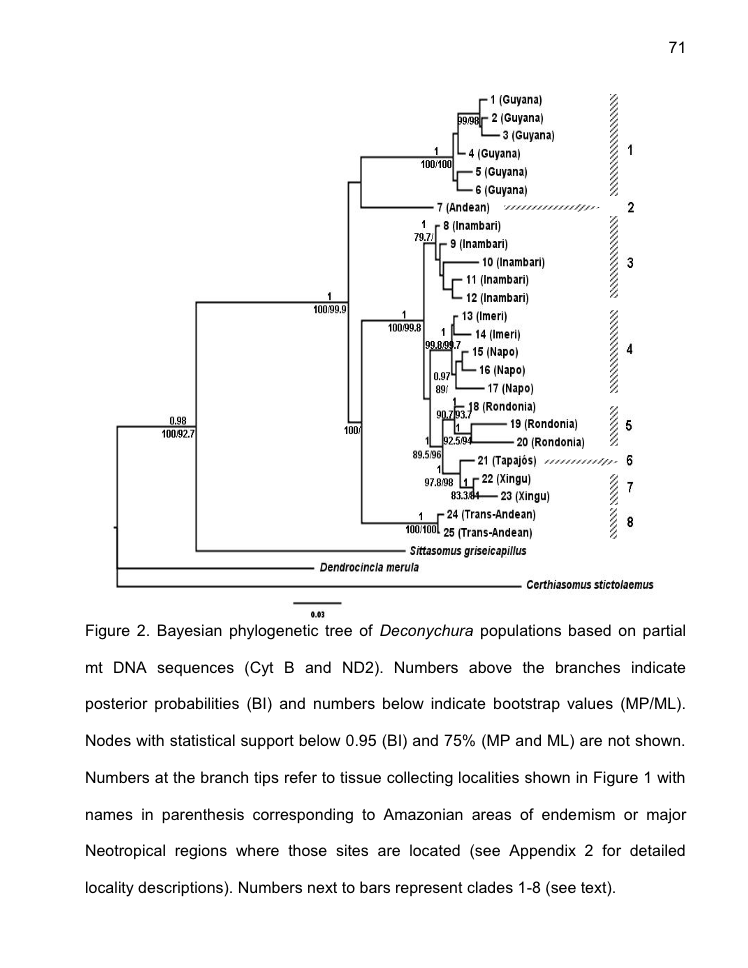

Barbosa (2010) presented sonograms for each of

the 8 well-supported clades found in the genetic analysis; those 8 clades

include the 3 recognized as species by BLI/HBW plus the undescribed foothill

taxon plus and additional 3 clades within the Amazonian pallida

group.

They all appear qualitatively different, but as

noted by Boesman (2016), there are problems with taking each sonogram as

representative of the clades because of small N, differences in “motivation”

(as emphasized by Marantz et al. 2003 for interpreting woodcreeper

vocalizations in general). Further,

although longicauda and typica appear distinctive, so to varying

degrees do some of the groups within pallida. I suspect this is in part due to

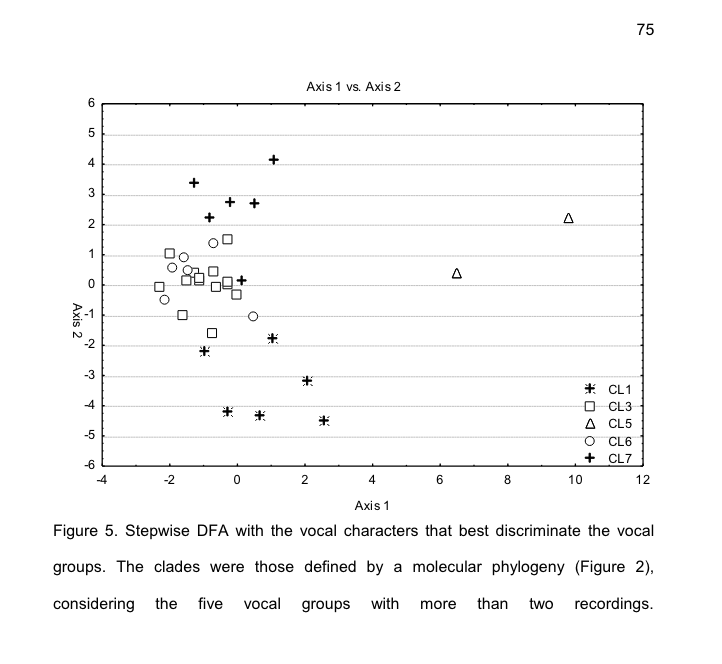

non-homologous vocalizations, but it’s hard to say. Barbosa’s Discriminant Function Analysis of

standard vocal characters shows that one of the pallida clades (5) is

actually the most distinctive, and that clade 1 (longicauda sensu

stricto) is actually more similar to some of the pallida group than are

some pallida clades to each other, although this may be a consequence of

the way characters are scored.

Barbosa’s (2010) genetic data (mt DNA gene

trees) are presented below:

Note that clade 1 represents longicauda,

clade 2 the undescribed Andean foothill taxon, clades 3-7 pallida, and

clade 8 typica. My personal view

is that these data say nothing about taxon rank per se.

Recommendation: I don’t have a strong

recommendation. When I listen to

cherry-picked sample recordings, my subjective reaction is “have to be

different species”:

• typica from

Puntarenas: https://xeno-canto.org/168203 (by Chris Benesh).

• longicauda

from Sipaliwini: https://xeno-canto.org/519473 (by Rolf A. de By)

• what would become

nominate pallida (type loc. rio Purus) from Rondônia: https://xeno-canto.org/427298 (by Caio Brito).

But there are dangers in that approach, and I

can see the rationale for waiting for more detailed, published analyses,

especially given the tricky nature of dendrocolaptid vocal analysis.

In support of a split, note that typica

was formerly treated as a separate species (e.g., Ridgway 1911, Cory &

Hellmayr 1925) and was subsequently treated as conspecific with D.

longicauda without published rationale (as far as I can find).

English names: A separate proposal would be needed

for English names if this one passes.

Perhaps we can do better than the somewhat misleading and insipid names

used by BLI, but I’m not optimistic.

References:

Barbosa, I. 2010. Revisão

sistemática e filogeografia de Deconychura longicauda (Aves -

Dendrocolaptidae). MSc Thesis. Universidade Federal de Pará, Belem.

Boesman, P. 2016.

Notes on the vocalizations of the Long-tailed Woodcreeper (Deconychura

longicauda). HBW Alive

Ornithological Note 78, In: Handbook of the Birds of the World Alive. Lynx

Edicions, Barcelona.

Marantz, C. A., A. Aleixo, L. R. Bevier, and M. A. Patten. 2003. Family Dendrocolaptidae (woodcreepers).

Pp. 358-447 in "Handbook of the Birds of the World, Vol. 8.

Broadbills to tapaculos." (J. del Hoyo et al., eds.). Lynx Edicions, Barcelona.

Van Remsen, May 2024

_________________________________________________________________________________________________

Comments

from Lane:

“This is a topic that has been on my mind a long

time, and I reviewed Barbosa's dissertation work with many comments and

suggestions while it was still in the works, but it appears he incorporated few

of them, which makes me reluctant to accept his results at face value. Among my

concerns were: 1) he had a few specimens that he misidentified to taxon through

a misunderstanding of localities. 2) he made little to no effort to control for

vocal variation due to agitation to playback versus "calmer"

emotional state, and given the small sample sizes of recordings he used in his

comparisons, this resulted in magnifying differences that are probably not

real, and 3) he completely ignored minor Todd, 1917 (type loc. El

Tambor, Santander; recognized by Peters 1951) as a taxon

worth investigating, simply lumping it in with typica and darienensis,

without much rationale.

“That said, his phylogenetic tree does show that it is necessary

to split Deconychura up into several species, and there is strong voice

distinction that correlates with this. The present 3-way split (plus the

undescribed Andean taxon that Jonas Nilsson and I and others have a manuscript

in the works to describe) seems to be the best move with current phylogenetic

and voice information available to us. I think minor, presently nearly

unknown in life, may be another taxon to keep an eye on, and I believe Andres

Cuervo has re-encountered it recently, so I am interested to see how that

shakes out.

“So at present, between Barbosa's dissertation and my own

experience with several of the forms, I would say YES to splitting Deconychura

up into three named species as listed in the proposal, with the Andean taxon

yet to be described as a fourth:

D. typica (including darienensis,

but with the caveat that minor probably doesn't belong here)

D. longicauda

(monotypic)

D. pallida (including

all other Amazonian lowland forms for now).

“A more in-depth study may require more fine-tuned splitting of

the pallida complex, and minor, but for now, this is the best option.”

Comments

from Claramunt:

“YES. Songs and genetic data suggest the presence of fairly divergent lineages.

In particular, the separation of typica from the Amazonian taxa seems supported

by both. Phenotypic differences are subtle, some claimed to be diagnostic but

with no formal analysis. But subtle differences in the shape of the light spots

or the extension of spotting across the plumage should not be disregarded as

insignificant, as woodcreepers are very conservative in plumage and such

differences are associated with species-level taxa in other genera. At the very

minimum, we have to accept that the historical lumping of typica into longicauda was done without presenting any

evidence, and we don’t have any evidence today. On the contrary, songs and

mtDNA suggest a clear divergence between the two. For the separation of pallida from longicauda, the vocal and

genetic evidence also show similar levels of divergence and I don’t see any

evidence of gene flow or admixture between the nominate form and the other

Amazonian forms. Therefore, having similar evidence, the conclusion should be

the same: separate species. Once the situation of the Andean clade is clarified

we can revisit this problem.”

Comments

from Stiles:

“YES to the 3-way split of Deconychura longirostris. I note that the

species epithet longirostris was proposed in Natterer’s (unpublished?)

catalogue in the genus Dendrocolaptes, but was apparently first

published by Pelzeln (1868) in the genus Dendrocincla. The genus Deconychura

was named by Cherrie (1891) with the species epithet typica as its

type species. Again, I presume that a proposal pending regarding E-names will

be forthcoming. As an aside, I recall seeing a recommendation (but I

unfortunately can’t recall where) to discourage use of the name typica for

proposed type species because with generic transfers, this could result in

messy homonyms.”

Comments

from Robbins:

“NO. Given the widely recognized limitations of using cyt B and ND2 for

discerning species limits coupled with concerns of comparing appropriate

primary vocalizations, I lean for waiting until there is a more complete

assessment of this complex before making changes. Clearly, plumage morphology does not add

insight into species limits within this complex. I look forward to Dan et al.’s

upcoming paper that will address some of the issues that he brings up in his

comments on this proposal. At that

point, it may become clear just how many species should be recognized.”

Comments

from Jaramillo:

“YES – Thanks Dan for your comments, they persuaded me at least. I suggest

Short-tailed longtailed Woodcreeper as a name for one

of the taxa.”

Comments

from Curtis Marantz (voting for Remsen): “YES. Based on my

field experience with at least several of the Amazonian taxa, the work that we

did putting together the HBW account, and the genetic work done subsequently by

Barbosa, my feeling is that the split of this complex into three species is

well supported. I know nothing about the recent Andean taxon, and

therefore cannot comment on it, but it appears that this one can be dealt with

following the publication of a description.

“We knew even before the HBW accounts were published that there

were multiple vocal groups, with the Central American ones being especially

distinct, and both looking and sounding much like what is now recognized as Certhiasomus,

which the genetics appear to show as being quite different. The genetic, morphological, and vocal datasets

all support recognition of this complex as a full species, especially given

that there appears to be no real justification for lumping it with the

Amazonian taxa in the first place.

“The Amazonian populations present a more complex situation. Despite their morphological similarity, D.

longicauda is moderately different vocally from the members with which I am

familiar in the pallida-group. I

will nevertheless note that, in my opinion, the vocal differences between these

groups represent more a case of moderate variation on a theme rather than

totally different themes, as is true for the Amazonian versus Central American

groups. Moreover, within

"Southern" Long-tailed Woodcreeper group, which I might add is poorly

named because it occurs almost as far north as does the "Northern"

Long-tailed Woodcreeper, I find minimal variation in the songs. Looking at the sound spectrograms shown in

Figure 4 of the proposal taken from Barbosa, I would have to argue that the

representative examples were either based on a very small sample of

unrepresentative recordings, or instead, they were "cherry picked" to

show differences that are unlikely to be real. For comparison, check out the songs in the

four recordings at the links below taken from widely separated locations within

the range of the pallida-group, and clearly representing both D. l.

pallida and D. l. connectens as the ranges of each are described. (Ignore the black squares – they come with

the link and can’t be deleted without deleting the link.)

Ucayali, Peru - ML127031131 - Long-tailed Woodcreeper - Macaulay Library

|

Para, Brazil - ML115073 - Long-tailed Woodcreeper (Southern) - Macaulay

Library

|

Napo, Ecuador - ML343373841 - Long-tailed Woodcreeper - Macaulay Library

|

Amazonas, Venezuela - ML65714 - Long-tailed Woodcreeper (Southern) - Macaulay

Library

|

“Having just looked superficially at the spectrograms and listened

to a song or two from each recording, I will not deny that there could be

subtle differences in the songs included in each of these recordings, but to

me, they sound pretty much the same. Moreover, almost more so than any woodcreepers

that I know, Deconychura can get really worked up after playback, and

they can emit a wide variety of sounds, so one must be careful t compare songs given under similar motivational states,

this being most easily done by looking at natural songs that were not recorded

during a territorial dispute.

“This said, I do think the song differences between nominate D.

longicauda and the pallida-group are consistent, and when used in

combination with the genetic data, probably sufficient to treat these two

groups as separate species.

“Given the morphological, vocal, and genetic variation presented

in our HBW accounts, Barbosa's thesis, and the proposal, I do feel that

treating Deconychura as three species is warranted. The decision about whether to split these

populations up now, or instead, wait until more information is available for

the new Andean population and those in the zone between the Amazonian and

Central American forms in Colombia is

another issue. I suppose I fall more in

the camp of waiting until the whole picture is clear before making changes,

which is why we treated these populations as one species for HBW even though we

knew that more than one species was almost certainly involved. Given my experience with at least several of

the Amazonian populations, s exemplified by the recordings above, I do not see

support at this point for further subdividing the pallida-group into

multiple species.

“Given their scientific names, I might

suggest naming the typica-group the Little Woodcreeper, keeping

Long-tailed Woodcreeper for D. longicauda, and maybe Pallid Woodcreeper

for D. pallida, though admittedly, it is not overly "pallid"

as far as woodcreepers go... “

Additional

comments from Remsen:

“Curtis, inspired by Alvaro and clearly trying to audition for a voting

position on SACC for English names, further made the following, logical

suggestion, perhaps implicit in Alvaro’s:

Little Long-tailed Woodcreeper

Long-tailed Long-tailed

Woodcreeper

Short-tailed Long-tailed

Woodcreeper”

Comments from Areta: “YES. I am not enthusiastic about this kind of

splits. I would really like to see the paper describing the new taxon and

assessing the species limits in Deconychura

as a whole, which will surely provide solid nomenclatural and taxonomic

assessments. I admit that it is difficult, at this point in time, to recognize

a single species when the information is screaming that there are multiple

species. I do not see the need for rapid assessments when there is people

working in good, detailed studies that will shed light on this. This being

said, I support the 3-way split that has been around for a long time.”

Comments

from Bonaccorso:

“NO. The song differences are compelling, but the

vocal analysis is based on a handful of recordings. The plumage differences

don´t seem to add much; I think they are far from diagnostic, although that

seems to be the case for many good species in this group of birds. I think more

genetic information (nuclear loci) based on more specimens, especially at

potential contact zones, are needed.”

Comments from Andrew Spencer (voting for Del-Rio): “YES -

There's not much I can say here that hasn't already been said by previous votes

for the split, but to reiterate: the vocalizations of these groups are so

drastically different, especially in typica, that I

think the burden of proof is squarely on those who want to keep them together.

I personally feel that in the age of enormous sound collections that are

continually vetted by experts from all over the world, that requiring the

perfect rigorous analysis in cases of obviously very divergent vocalizations is

overkill. Yes, I'd love to see that analysis. But I don't think we need it to

state the obvious that has already been thoroughly vetted. Also, and this is

purely circumstantial and minor evidence, I have played the songs of southern

birds to individuals in Costa Rica and Panama and was completely ignored. Both

before and after playback of typical typica (ha that

was fun to write). And I have also played

typica to a bird at Cristalino, Mato Grosso,

with the same lack of response.”

Comments from Zimmer: “YES to the

proposed three-way split. Even given

some of the problems with the vocal analyses of Barbosa (as highlighted by Dan

and Curtis), the vocal differences between the typica-group and both longicauda

and the pallida-group are not even in the same ballpark in my opinion,

and the distinctiveness of the typica-group is further supported by

morphometric and (to a lesser extent) plumage differences, as well as by the

genetic data from Barbosa (2010). That

the Central American birds were described as a species separate from longicauda,

and subsequently lumped without justification, is all the more reason to split

them in my opinion. I would also add,

that like Andrew Spencer, I have conducted informal playback trials by

presenting individuals of typica, encountered on the Pacific Slope of

Costa Rica (specifically, in Carara NP, and the

Wilson Botanic Gardens), with playback of songs of various subspecies in the pallida-group

that I had personally recorded in Brazil, and had zero response. I have performed similar trials, using

playback of recordings of typica from Costa Rica to pallida-types

at various spots south of the Solimões/Amazon in Brazil, and had identical zero

response, and this, from birds that were highly responsive to geographically

appropriate, taxon-specific vocalizations.

So, in sum, the split of the typica-group from the others is a

slam-dunk in my opinion.

”I also feel that N bank longicauda

is vocally distinct from everything I’ve encountered on the S bank of the

Solimões/Amazon, and although these vocal distinctions are not as striking as

those of Central American versus Amazonian populations, they are, to my ears,

both significant and consistent, and the genetic data of Barbosa (2010) further

support treating nominate longicauda as distinct from the pallida-group. That’s as far as I’m willing to take it at

this point. I know nothing about the

Andean population that Dan is working on, nor do I know anything of minor,

so I have nothing to add there. As

regards the 3 additional clades that Barbosa recovered within the pallida-group,

I remain unconvinced regarding the purported vocal distinctions. Echoing the concerns of others regarding the

problems of small sample sizes, lack of proof that homologous vocalizations are

being compared, and lack of accounting for the motivational state of the

audio-recorded individuals involved, I’m reluctant to give the qualitative

distinctions evident in Barbosa’s spectrographs too much weight. The importance of the motivational state of

the recorded birds cannot, in my opinion, be emphasized enough. As Curtis states in his comments,

woodcreepers in general, but particularly these pallida-types, can get

really wound-up by playback. One thing

that I’ve noted in particular among pallida, is that when presented with

playback, they have a decided tendency to modulate the frequency of each note,

often dramatically so, which can change the entire quality of the song, in

addition to changes in pace, and total number of notes. This tendency, when coupled with small sample

sizes, could result in spectrographs that seriously inflate perceived

differences in songs. In summation, I would vote YES to the suggested 3-way

split, but hold off on any further action until Dan & co-authors sort out

some of these remaining issues.”