Proposal (999) to South

American Classification Committee

Treat Sakesphorus pulchellus as

a separate species from S. canadensis

Note:: This is one of

several situations that the IOU Working Group on Avian Checklists has asked us

to review because published treatments of the species differ, and WGAC has to

pick one. BirdLife International (del

Hoyo & Collar 2014) now treat these two as separate species. This is a complex situation about which I

have no first-hand knowledge, so my goal here is to lay out as many facts as

possible that might be of potential relevance.

Background: As

currently defined, Sakesphorus canadensis consist of 6 subspecies,

although Zimmer & Isler (2003) noted that the validity of some was

questionable due to apparent clinal variation:

• S. c. pulchellus (Cabanis & Heine, 1860) – n.

Colombia and nw. Venezuela

• S. c. intermedius (Cherrie, 1916) – e.

Colombia, s. Venezuela, n. Brazil

• S. c. trinitatis (Ridgway, 1891) – ne.

Venezuela, Trinidad, Guyana

• S. c. canadensis (Linnaeus, 1766) – Suriname, n. French

Guiana

• S. c. fumosus Zimmer, 1933 – s.

Venezuela in s. Amazonas

• S. c. loretoyacuensis (Bartlett 1882) – riverine

distribution in extreme se. Colombia, ne. Peru, and w. Amazonian Brazil

Restall et

al. (2006), however, also recognized two additional subspecies: paraguanae Gilliard, 1940, from coastal NW Venezuela

(type locality from Paraguaná Peninsula) and phainoleucus Todd, 1916, from ne. Colombia and nw.

Venezuela (type locality Rio Hacha). Restall et al. gave characters for both of

those in addition to characters for intermedius and trinitatis. This must be taken seriously because Restall

et al. based their conclusions on the world’s best collection of Venezuelan

birds, the Phelps Collection. Cory and

Hellmayr (1924) treated phainoleucus as a

synonym of pulchellus with the following footnote from Hellmayr, which

implies that Todd actually then agreed with him:

“Birds from the Goajira Peninsula and nw. Venezuela (Rio Aurare, se. of Altagracia, Zulia; Barquisimeto, s. Lara)

have slightly larger bills, more white on forehead, the sides of the head

mainly white, and less black on the under parts, this

color being, on

the throat, sometimes nearly concealed by the white apical portions of the

feathers. As, however, about fifty percent of the specimens are

indistinguishable from pulchellus, of nw. Colombia, I agree with E. W.

C. Todd that the recognition of phainoleucus

is of no practical advantage.”

Peters

(1951) listed paraguanae as a synonym of phainoleucus, and del Hoyo & Collar’s

supplemental material (see below) treated them both as synonyms of pulchellus

because they “appear to intergrade with pulchellus.” As stated, that makes no sense to me –

parapatric subspecies should intergrade at the contact zone. If they didn’t, it would be prima facie

evidence for a hard barrier to gene flow and hence full species rank.

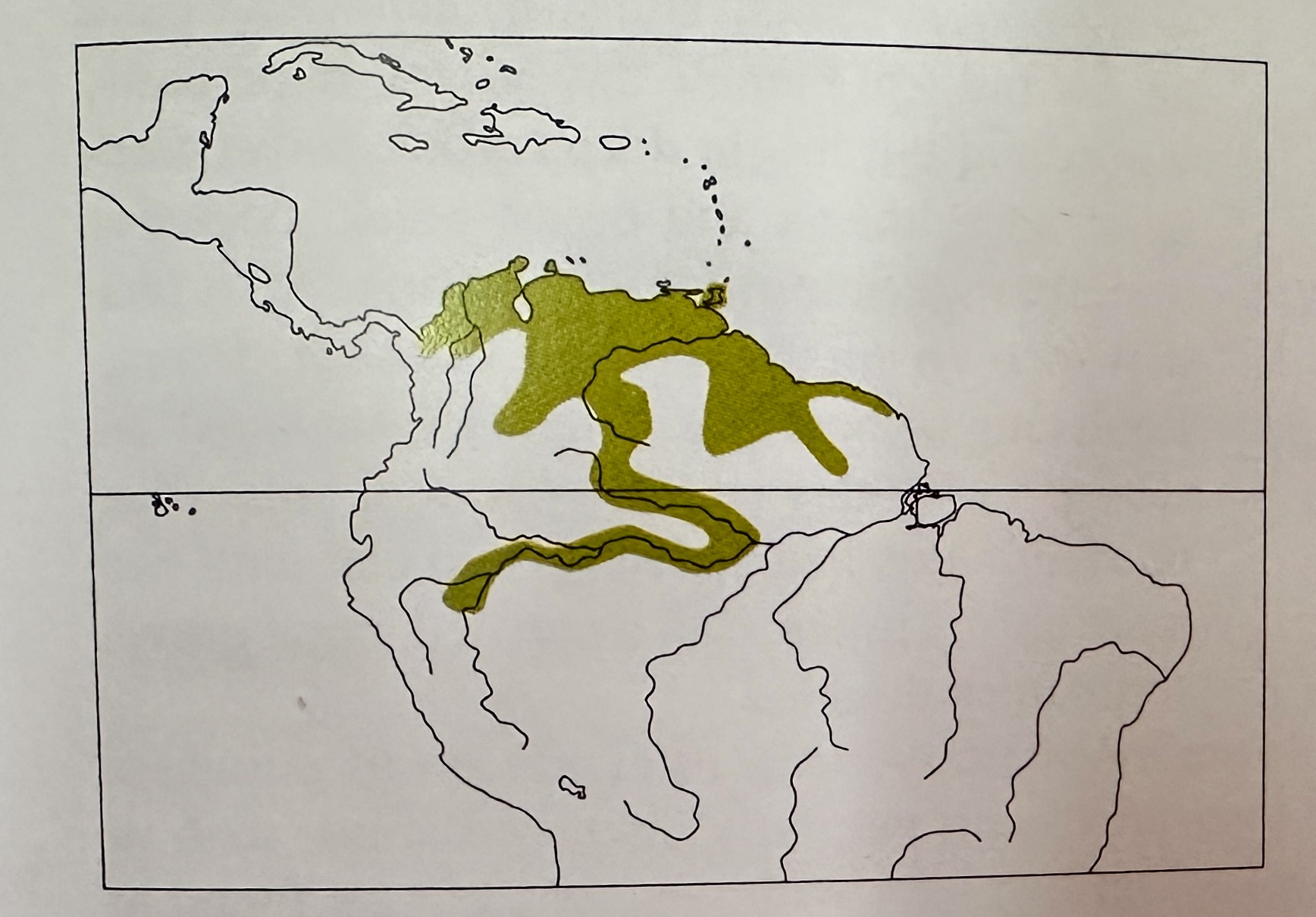

Here is the composite distribution of S. canadensis from

Zimmer & Isler (2003):

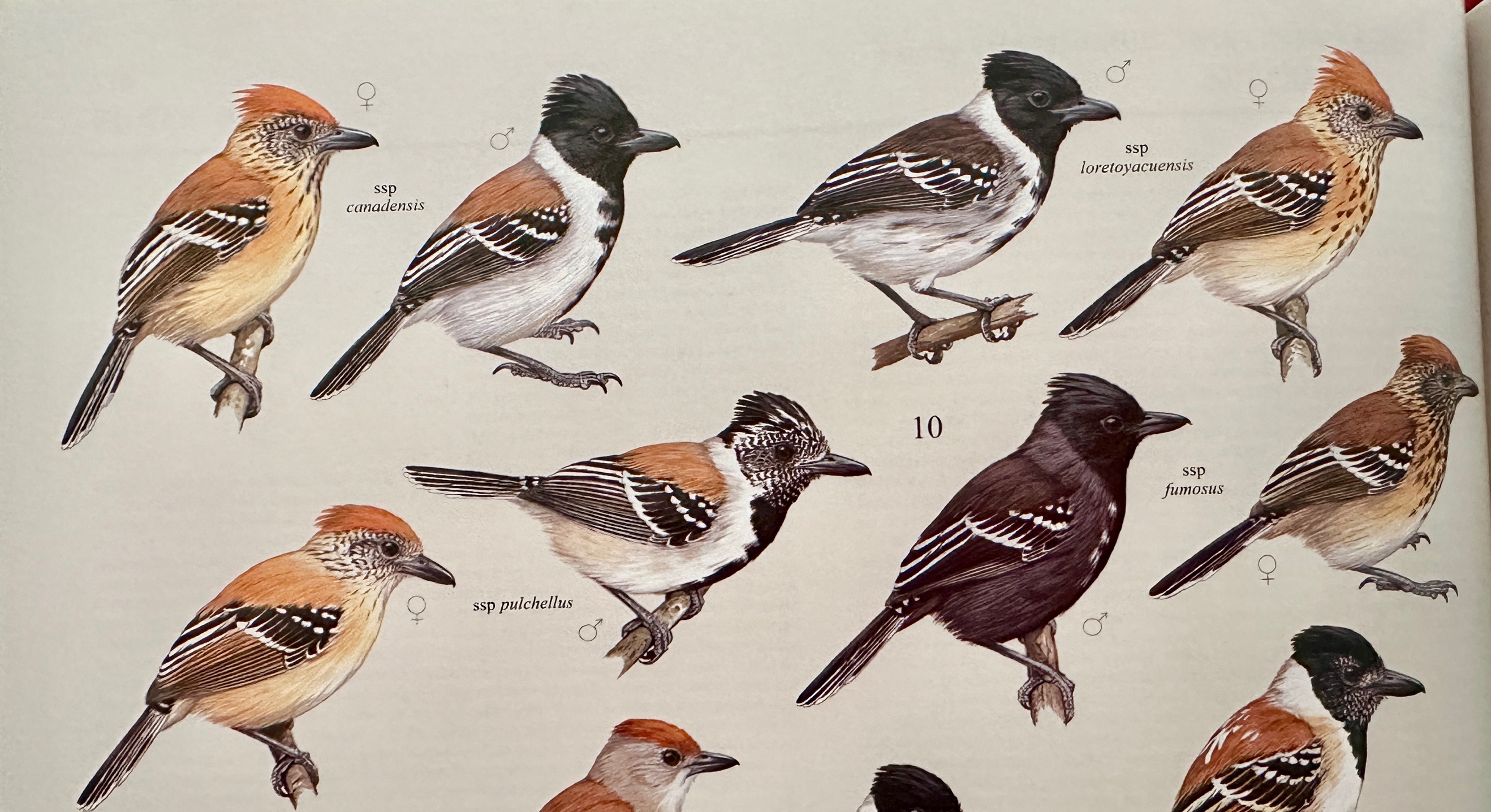

Here

is the terrific plate by Hilary Burn from Zimmer & Isler (2003), which

illustrates canadensis, pulchellus, loretoyacuensis, and fumosus. Trinitatis and intermedius (not

shown) are “very similar to nominate canadensis” (Zimmer & Isler

2003), and Cory & Hellmayr (1924) basically provided sufficient evidence in

their long footnote to treat them as clinal variation within a more broadly

defined canadensis; in retrospect, I (in Dickinson & Christidis 2014)

perhaps should have treated them as synonyms of the nominate subspecies because

Cory & Hellmayr’s (1924) qualitative assessment of them was sufficient to

put the burden of proof on maintaining them as separate taxa, and they treated intermedius

as a synonym of trinitatis. Note

that Zimmer & Isler (2003) didn’t even try to describe the differences

between intermedius and trinitatis versus the others because,

evidently, they were so subtle, although see Restall et al.’s subsequent

diagnoses of these subspecies. Peters

(1951) retained intermedius, perhaps on the basis of an analysis I

haven’t found. Cherrie (1916) described intermedius

as follows (and note that the paleness would be “in the direction” of pulchellus):

“Birds from the middle Orinoco, from Ciudad Bolivar,

and beyond, are intermediate in general color between the Cayenne birds and

those from Trinidad, the Orinoco delta, and Caura River points, being as a

series, at once distinguishable by their paler coloring both above and below.

This pale coloring is perhaps more marked in the females, but is very evident

in the males also when compared as a series. So characteristic does this paler

form seem of the middle Orinoco region that I would designate it as … HYPOLOPHUS CANADENSIS INTERMEDIUS subsp. nov.”

Based

on this plate, it looks to me that we have taxa in which both male and female

plumage roughly follow Gloger’s Rule, with the taxon from the driest area (pulchellus)

the palest, and the one from perhaps the wettest area (fumosus) the

darkest.

Here

is our current SACC note:

2h. The northwestern subspecies pulchellus

differs vocally from the others and may merit recognition as a separate species

(Zimmer & Isler 2003).

As far as I can tell, Ridgway

(1911) was the first one to treat pulchellus as a subspecies of S.

canadensis, and no rationale was provided nor does his synonymy indicate a

previous publication that had done that.

I can see the rationale, however, in the plate above – without checking

specimens, pulchellus superficially looks like a canadensis that

shows white streaking and freckling in the face, crown, and throat – other than

that, those two appear to resemble each other more than either does to loretoyacuensis

or fumosus. Cory & Hellmayr

(1918), Peters (1951), and all subsequent classification except del Hoyo &

Collar (2016) have treated them as conspecific.

Zimmer (1933) described fumosus

from 6 specimens taken near of Mt. Duida in Venezuela; he noted that two of the

males from “Río Cassiquare” [Casiquiare] not as

solidly black as the type in that “the irregular whitish marks on the sides of

the breast and belly slightly larger.”

He also looked extensively at variation in canadensis, and his

comments are worth noting here in full because (1) they illustrate in detail

the complexity of the situation, and (2) they underscore the problem of

assigning Tobias et al. plumage scores to taxa.

I suggest at least a skim, although it doesn’t get much better than a

full dose of Zimmer’s style:

“I am not able to adopt unreservedly the

arrangement proposed by Hellmayr (Field Mus. Nat. Hist. Publ., Zool. Ser.,

XIII, pt. 3, p. 53, 1924) which assigns all of the Venezuelan birds (except

pulchellus of the Lake Maracaibo region) to trinitatis; yet, with fewer

skins than the series examined by Hellmayr, I would hesitate to make a counter proposal

were it not for certain new material at hand which helps to explain some of the

puzzling factors in Hellmayr's arrangement.

“With the establishment of typical canadensis

in French and Dutch Guiana, the birds from Trinidad are recognizable under the

name trinitatis. I have only two males from British Guiana, one of

which, labeled "Demerara," is not unlike Trinidad males while the

other, collected by Alexander and possibly from the eastern portion of the

country, is much like true canadensis. The difference between the males

is small and, without females from various parts of British Guiana, it is

impossible to say whether or not both forms occur in this country.

“In the Orinoco Delta region and in the

former state of Bermuidez (now Anzoátegui and

Monagas), the birds are very like the Trinidad examples.

“Farther up the Orinoco, at Ciudad

Bolivar, Caicara, and the Rio San Feliz, there is a

prevailing tendency toward lighter coloration than is shown in the delta

region. The males are brownish on the back, rather than grayish, but the tone

is light, and the lores are decidedly whitish. The under tail-coverts are

largely white, sometimes grayish subterminally but without a strongly blackish

area in that position such as occurs in canadensis and trinitatis.

The sides and flanks are light gray or even whitish, in reduced contrast to the

white area bordering the median black stripe. The females also are pale brown

on the back, and are light rufous on the crown, pale ochraceous below, with

only moderately heavy streaking on the breast, and with the belly distinctly (though

restrictedly) white in the middle. The same style of coloration, possibly a

trifle warmer, is exhibited by birds from the Rio Surumú,

Brazil, an affluent of the Rio Cotinga. The region of the Surumui

is largely savanna country, I am informed by Messrs. Tate and Carter, who

visited the locality, and savanna occurs at places on the top of the Pacaraima

Range and at the headwaters of the Rio Caroni in Venezuela and it may extend,

at least brokenly, down to the middle stretches of the Orinoco. Consequently it

seems entirely possible that a light-colored race may exist in these savannas.

Since the Caicara bird has been named intermedius

by Cherrie, that name would be available for such a pale subspecies, if it can

be satisfactorily maintained.

“Birds from the state of Falcon are

neither typical trinitatis nor the Caicara

form but probably are nearer the latter though they are slightly darker. The

under tail-coverts are without blackish subterminal areas and the lores of the

males are rather extensively whitish. Possibly these birds should be considered

as intermediate between trinitatis and pulchellus which latter

form inhabits the nearby state of Lara, but, even if so, the similarity to intermedius

may necessitate their reference to that subspecies. An additional character

noted in the two males from the state of Falc6n, but not observed in skins from

other regions nor in Falcon females, is a small whitish area on the inner webs

of the tail feathers at their extreme base. Its significance is not clear. In

any case, material must be examined from the region between Caicara

and the state of Falcon to determine the possible continuity of range. Since

the region is one of savannas, direct connection is not unlikely. Nevertheless,

Hellmayr and Seilern (Arch. Naturg., LXXVIII, A (5),

p. 119, 1912) found three males from San Esteban, Carabobo, to be more grayish,

less rufous, above than others from British Guiana, Trinidad, and the Rio

Branco, Brazil, being like skins from the Caura region and San Fernando de

Apure!

On the Río Caura, a different type of

coloration is encountered which is not that of Caicara

and Ciudad Bolivar although the Caura empties into the Orinoco between these

two places. Judging by the darker hues, the Caura birds are inhabitants more of

forests than savannas and, from available accounts, the Caura is marked by this

type of habitat. Some relationship to the forest-inhabiting fumosus is, therefore,

to be expected. Four males from as many localities (Río Mato, Suapure, Maripa, and La Uni6n)

all have the white stripes bordering the median black area of the under parts

virtually obsolete, being dull and grayish and not distinguishable as

sharply-defined white; the lower belly is quite sooty, not white. The

metacarpal border of the under wing-coverts is broadly black in the Río Mato

male, with white tips in the Maripa skin, intermediate

in the other two; the under tail-coverts have blackish bases and relatively

narrow white tips; the male from La Uni6n has the lores quite black, though the

three other males have much white in this region. All these tendencies are in

the direction of fumosus. The back is rather plain, without the heavy

streaks of fumosus but of a darker tone than in intermedius. An

additional character of doubtful significance is the decided reduction of the

white spot on the lateral margins of the outer pair of rectrices. Instead of

the customary broad patch reaching from the shaft to the margin, there is only

a narrow marginal streak, rarely supplemented by a small oval spot in the

middle of the web. A young male has the patch of exceptionally large size,

connecting on the left rectrix with the white at the tip of the feather. In the

Caura females the patch is of the regular size or but slightly reduced, and, in

addition, the general color of both upper and under parts is as near to that of

female intermedius as to that of fumosus, being intermediate

between the two, as in the males. The general impression left by the Caura

birds of both sexes is that of intermediates between intermedius and fumosus,

not definitely referable to either.

“In the neighborhood of the upper Orinoco,

above Caicara, from Maipures

to the falls of the Atures at Ayacucho, another

definite change of color and pattern is found which bears little relation to

the Caura series. The males from this region are even darker and more rufous

brown on the back than the Caura males with the added features of rather prominent

dusky streaks and an evident, though very small, concealed patch of white on

the mantle. The white patch on the outer margins of the outer rectrices is not

reduced in size but the lores are noticeably whitish. However, the under parts

have not lost any of the broad white areas but rather have this white more

decidedly in evidence than usual and the lower belly is white, showing no

approach toward fumosus in these respects. I have no females from this

part of the Orinoco, but a young male from the "Upper Orinoco"

(judging by the collector's dates, not far from Maipures)

is very like the young male from the Caura (Maripa)

and, like it, has unusually extensive white on the outer margins of the outer

rectrices, but is a little duller on the mantle. [Curiously enough, a young

male of intermedius from the Rio Surumú,

Brazil, and one from Ciudad Bolivar, Venezuela, also have the white spots of

tip and outer margin of the outer rectrices continuous, with a small subterminal

spot of dusky on the outer web, and a young female of trinitatis from

Las Barrancas, Rio Orinoco, has the same continuity without any dusky spot, as

in pulchellus. An occasional skin of pulchellus shows a

subterminal dusky spot and one male from La Cienega, Santa Marta, has the

marginal patch connected with the terminal spot only by a very narrow line on

the outer margin of the outer web.] There is a tendency toward the development

of white not only on the lores, as mentioned, but also on the forehead and

superciliary region (as well as in the malar region where it appears frequently

in other forms). The under tail-coverts are grayish as often as sooty and are

quite broadly tipped with white which conceals the darker basal portions. The

nearest affinity, in several of’ these respects, is pulchellus which

occurs southeast of Lake Maracaibo though on the far side of the cordillera

which separates the drainage of this lake from the rivers flowing to the upper

Orinoco.

“A single male from San Fernando de Atabapo, between Ayacucho and Mt. Duida, is more like fumosus

than are the Ayacucho birds, but it still has the white on the sides of breast

and belly and the streaked upper parts with more of brown than of black though

the brown is grayer and Jess rufous than in Ayacucho males. Resemblance is

apparent to some loretoyacuensis, which probably is due not to racial

consanguinity but rather to a parallelism reached in the transition from fumosus

to pulchellus or intermedius.

“The only other skin which needs special

mention is a male from Caracarahy, on the middle

stretches of the Rio Branco, Brazil. This bird is plain brown on the mantle, of

a darker hue than that of intermedius from the affluents of the upper

Branco; in other respects it resembles loretoyacuensis. Since it comes from a

locality in the region where the ranges of these birds must meet, it may be

considered as intermediate between them.

“In spite of the apparent regularity of

the variations on the Caura and at Ayacucho and Maipures,

and the impossibility of referring the respective series to one form or

another, I hesitate to name new forms from these two regions. Obviously fumosus,

as an inhabitant of forested areas, finds its way across the Pacaraima Mts. to

the upper Caura which is forested, and extends down that stream in somewhat

modified form, affected, probably, by some contact with the paler intermedius

of the savannas which is more prevalent to the east and northward.

“On the other hand, descending the

Orinoco, an earlier contact occurs with savanna-covered regions, and a

different modifying factor may exist in pulchellus some distance to the

northwestward, resulting, in any event, in a somewhat different combination of

characters as outlined above. Until more material is available from other

localities I can do no more than suggest the lines of possible relationship.”

New information:

Del Hoyo & Collar (2016)

treated pulchellus as a separate species (“Streak-fronted Antshrike”)

from canadensis and other 4 subspecies.

Unfortunately, their plate places the illustrations of pulchellus

and nominate canadensis on opposite sides of the page so that the similarities

in plumage are not emphasized. Del Hoyo

& Collar’s assessment using the Tobias et al. point scheme is as follows

(courtesy M. Iliff):

“Streak-fronted: https://birdsoftheworld.org/bow/historic/hbw/bkcant1/1.0/introduction:

Previously suggested as possibly deserving

of species status, but hitherto treated as race of S. canadensis.

Differs (in male) in its black hood shot with white (forecrown with white

streaks, white speckling on throat, head-side and supercilium) (2); upperparts

bright pale cinnamon vs dullish cinnamon-brown (or darker) (1); more white in

tail, with much larger white tips and all-white outer vane of outermost rectrix

(small white tips in other taxa) (2); more white on underparts (ns[1]); and

overall distinctive song, with slower pace and lower frequency at start, lower

maximum frequency (no overlap; 3), and last notes dropping vs rising in pitch

(3), with less acceleration (1). Proposed races phainoleucus

(Riohacha, in N Colombia) and paraguanae

(Paraguaná Peninsula, in NW Venezuela) appear to

intergrade with pulchellus, and are best rejected. Monotypic.”

As an aside, fumosus certainly would score more points based

on plumage vs. nominate canadensis than pulchellus does, and loretoyacuensis

also would likely to do so.

The vocal differences are based on Boesman (2016), who

documented substantial differences in the loudsong of pulchellus (N=6)

and “other races” (N=8): faster pace, last notes dropping in pitch, lower start

frequency, snarling notes at end, etc. I’m

a big fan of Boesman’s notes as catalysts to guide more thorough research, but

he pumped out 457 of these in a short time and just did not have the time to

get them into the shape that would be required for peer review. For example, It is not clear from Boesman

whether his 8 samples from “other races” included all 5 subspecies; he stated

that “song shows little variation among the different races, with the exception

of race pulchellus.” What would

be really critical is a comparison of songs from adjacent populations of trinitatis;

from range maps it would appear that there is a potential contact zone in north-central

Venezuela in the vicinity of Yaracuy-Carabobo and also south of Lake Maracaibo. In fact, here’s a footnote by Hellmayr from

Cory & Hellmayr (1924) that describes a specimen intermediate between pulchellus

and trinitatis:

“A single male from Catatumbo, sw.

of Lake Maracaibo, however, combines the general coloration above and the

extensive white tail-markings of pulchellus with the dark gray flanks

and the chiefly black sides of the head of trinitatis. More material is

required to prove the constancy of these characters or otherwise.”

However, I wonder if that is not in the range of intermedius

rather than trinitatis – the boundary between trinitatis and intermedius

is not clear to me.

Some sample recordings:

• pulchellus from n.

Colombia by Ross Gallardy: https://xeno-canto.org/353175

• trinitatis: from Aragua,

Venezuela, by Chris Parrish: https://xeno-canto.org/6209

• intermedius: from Apure,

Venezuela, by Joe Klaiber: https://xeno-canto.org/220949

• canadensis: from French

Guiana by Olivier Claessens: https://xeno-canto.org/42702

• loretoyacuensis: from Ilha

Anavilhanas west of Manaus by Thiago V. V. Costa: https://xeno-canto.org/14906; and from

Peru by Juan Díaz Alván: https://xeno-canto.org/87932.

• fumosus: from Roraima by

Jeremy Minns: https://xeno-canto.org/319232

My cursory cruise through the recordings supports everything that

Boesman said, especially the differences in the ending of the song. By the way, the differences in the song

endings of the pulchellus group were noted long ago by David Ascanio as

cited by Hilty (2003). On the other

hand, all the songs sound somewhat alike to someone like me who is not immersed

in antshrike song. Whether the

differences meet the Isler-Whitney criteria for species-level differences is

not obvious (to me).

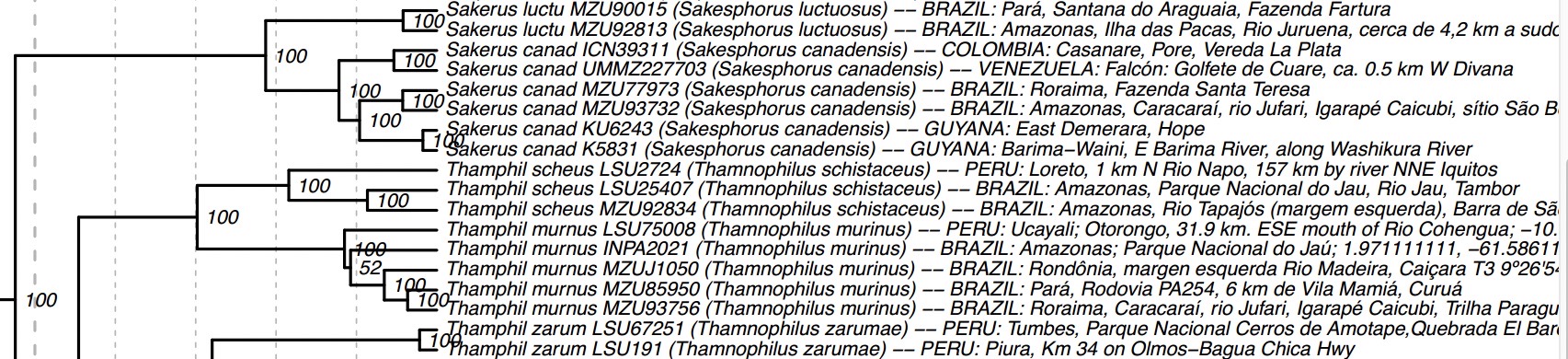

New genetic data: My view on genetic data and

species limits is that unless they reveal non-monophyly, they are not taxonomically

definitive. Using comparative branch

lengths and genetic distance is problematic in my opinion. Harvey et al.’s (2020) suboscine

tree shows the following branching pattern, strongly supported, for Sakesphorus:

The salient points here for me are:

1. I

originally thought that that the Casanare sample referred to pulchellus

because comments from WGAC voters stated this.

However, I am grateful to Ottavio Janni (pers.

comm.) for pointing out to me that a sample from Casanare would represent intermedius,

of del Hoyo and Collar’s narrowly defined canadensis group, NOT pulchellus,

as indicated in private comments from WGAC members. Therefore, pulchellus sensu del

Hoyo-Collar is a paraphyletic taxon that also conflicts with the vocal data.

2. If one

puts stock in genetic distance, the depth of the node that marks the split of

the three Thamnophilus schistaceus samples is considerably deeper than

the one that the comparable node for S. canadensis sensu lato. Also, the node that marks the split of the five

T. murinus samples is at the same depth as the comparable node for S.

canadensis sensu lato. I only

included a portion of the tree just to include the first Thamnophilus

branch. Whether the canadensis

node better fits the current taxonomic ranks of species vs. subspecies in Thamnophilus

would require more work.

Discussion

and recommendation:

I’m going to try to get an antshrike expert to take my vote on this because I

can see this both ways and am conflicted.

If there were a study of the likely contact zone between pulchellus

and trinitatis in north-central Venezuela, then this would be a simple

problem – do they intergrade there or not?

The same applies to pulchellus vs. intermedius. Even a densely sampled set of recordings from

that area would show whether the song characters change abruptly or not. If there were an analysis of the vocal

differences using the Isler-Whitney criteria, then that would also provide an

objective answer. But as is, we have

none of that. All we really have is a

summary of an analysis of 14 recordings, possibly but not certainly of all the

subspecies, and a sum of plumage character differences of which most individual

characters are typical of subspecies-level, not species-level, differences. Further, pulchellus is much more

similar overall in terms of plumage to the adjacent subspecies of canadensis

(trinitatis and intermedius) than those two are to other

subspecies that del Hoyo & Collar included in canadensis sensu

stricto. The fatal flaw in the del

Hoyo-Collar treatment the genetic data (Harvey et al. 2020) conflict with the vocal

data similarities, and refute treating their treatment of canadensis as

a species. Finally, I feel reluctant to

make any decisions on this complex until a thorough, modern analysis of

geographic variation is presented. Badly

needed is a study of character variation.

Every author who has commented on plumage variation has mentioned some

degree of variability within samples from within even a single taxon. The actual boundaries between taxa are also

unclear, at least to me. This make me

uncomfortable. All of these issues constitute

sufficient reason, in my opinion, to proceed cautiously in any such decision,

and so I strongly recommend a NO vote on this one.

English

names: If the proposal passes, I think we should

have a separate proposal on English names. Streak-fronted is excellent. However, leaving the rest of canadensis

with the parental name Black-crested will lead to perpetual confusion, i.e. the

same name, Black-crested Antshrike, would apply to two different taxonomic

treatments. Broadly defined Sakesphorus

canadensis has been known as Black-crested Antshrike or Something

Black-crested Antshrike since the dawn of English names for South American birds

(e.g. Cory & Hellmayr 2024). The

range of pulchellus is large; although not as large as canadensis

sensu stricto, it is far from being a peripheral isolate. So, if we follow our guidelines (C.1), then we should

coin a new name, perhaps something like Black-fronted Antshrike to maintain as

much of the connections as possible.

References (see SACC Bibliography for standard

references)

Boesman, P.

2016. Notes on the vocalizations

of the Black-crested Antshrike (Sakesphorus canadensis). HBW Alive Ornithological Note 52: In Handbook

of the Birds of the World Alive. Lynx

Edicions.

Van Remsen, June 2024

Addendum

from Remsen:

This proposal suddenly became a lot easier thanks to Ottavio Janni, who pointed out to me that the genetic sample from

Casanare (llanos of Colombia) must refer to intermedius, of the del

Hoyo-Collar species canadensis, NOT to pulchellus. I had overlooked this because WGAC internal

discussion erred in assuming it represented pulchellus, and I didn't

catch that mistake. From Ottavio Janni: “I noticed that in

discussing the Harvey et al suboscine tree you say that "the two samples

of pulchellus cluster together", but the Colombian specimen is from

Casanare in the llanos, so shouldn't it be intermedius? This is what the

Hilty guide shows. The eBird photos from Casanare, a handful of which are mine,

also show birds that belong to the canadensis group on plumage (https://media.ebird.org/catalog?taxonCode=blcant4&mediaType=photo®ionCode=CO-CAS), although some birds have more of a grizzled instead of

uniformly black face (I guess that's why whoever described them named them intermedius?).

It would be good to clear this up, if indeed pulchellus and intermedius

cluster together I guess that would weaken the case for splitting pulchellus,

at least genetically, though maybe voice can make the case alone?”

_____________________________________________________________________________________________

Comments

from Stiles:

“NO for the reasons stated by Van: this whole complex of Sakesphorus appears

to be something like a maze of discordant characters of genetics, distributions

and color patterns that needs to be straightened out with a more detailed study

that definitely requires more data on vocalizations.”

Comments from Areta: “NO. I am torn

by this case, which seems to be solid, but for which more comparative

information is missing. The vocalizations differ noticeably, and Paul Schwartz

realized about that a long time ago (see here: https://macaulaylibrary.org/asset/61724).

“I think that pulchellus

will eventually be split from canadensis,

and it is a great candidate. As in other cases, if we were starting from

scratch, I would start by calling it a species. However, I would like to see a

full vocal study to help clear any doubt and to provide a more robust picture

of geographic variation in S.

canadensis as a whole. I stress that, biogeographically, numerous

species are restricted to arid N Colombia and N Venezuela. Everything makes

sense for a split here, but I want to see a more thorough assessment that goes

beyond the obvious. So, a

painful NO, until someone publishes a deeper study, that will

surely show that pulchellus

is a different species.”

Comments

from Robbins: “NO. Van has

underscored the issues with evaluating the complexity of these Sakesphorus

and that alone should raise concerns about making any changes. Moreover,

subsequently more information has been provided that has underscored issues

with the allocation of both genetic and vocal data to appropriate taxa (fide

Ottavio Janni, Gustavo Bravo, respectively). Thus, this has become a mess and clearly

needs to be sorted out before any taxonomic changes be made.”

Comments from Claramunt: “NO. I think Van’s

arguments are very valid. We have only spotty information on plumage and songs

(and DNA) from a complex that shows marked geographic variation (at least in

plumage). Climate and/or habitat seem to be playing a major role in influencing

plumage variation, raising the possibility that the plumage variation may be

more climate-driven than indicative of relationships. The genomic data don’t

even support the separation of pulchellus alone. A

modern analysis of geographic variation is needed to gain a better picture of

species limits in this complex.”

Comments

from Jaramillo:

“NO at this time, this is a messy situation and requires a more complete

sampling of vocal characters as well as genetics.”

Comments

from Gustavo Bravo (voting for Remsen): “NO. As everybody

has very well pointed out, the situation is messy, and we lack sufficient data

to determine species limits. To me, it is critical to assess gene flow across

potential contact zones between pulchellus and canadensis (e.g.,

Táchira depression), and the extent of plumage and vocal variation across the

whole complex."

Comments

from Bonaccorso:

“NO. Although pulchellus has has enough plumage characters to be diagnosable, a better

understanding of contact zones and genetics (more samples across the

distribution of all the subspecies) is necessary to make an informed decision.

Also, a formal vocal analysis would be a huge plus to a future proposal.”

Comments

from Lane:

“NO. Whereas I suspect that a more thorough study of this complex will uncover

the evidence necessary to support this proposed taxonomic change, the evidence

simply isn’t available right now.

“I am troubled by the eagerness of WGAC to

influence change when the cases are woefully under-sampled. In fact, I question

the point of the WGAC efforts completely: to try to get all the major world

checklists aligned is a fool’s errand. The authors of all these competing

checklists clearly don’t use the same criteria for determining species limits,

or they would all already match, and most would be superfluous… but they don’t

match, and different users use these lists depending on their own ideologies

and purposes. And that we in SACC are asked to vote on cases, when other

checklists have already made up their minds, suggests that we are still able to

disagree with those checklists, and thus will not fall into line with the other

WGAC members, correct? So…. What’s the point here? In most cases, the evidence

available simply isn’t sufficient to allow us to make an informed decision by

SACC’s usual standards, so either we abandon those standards, or we are forced

to settle for substandard or (more often) entirely incomplete evidence. This

may not matter to many checklist users (some or most of whom just want more

species to tick off), but it does mean that any student looking for a potential

project will simply assume that many of these poorly supported scenarios are

“already settled” when in fact they are very much not. To me, that is a harmful

side effect of jumping to conclusions without sufficient evidence.”