Proposal (992) to South

American Classification Committee

Treat Tyto furcata as

a separate species from Barn Owl Tyto alba

Background:

Two

recent proposals to NACC (2018-C-13 and 2022-B-6) have considered the

taxonomic placement of various taxa within the Barn Owl (Tyto alba)

complex. Comments on both NACC proposals and one submitted concurrently to SACC

(#908) raised concerns about

the lack of analysis of vocal differences among taxa.

Although

pointed out in comments under the previous proposals, we highlight here a

distinctive and prominent flight call associated with mate attraction that is

uttered by New World Barn Owls and is absent in Old World Barn Owls. Based on

this and concordant genetic data, we recommend adoption of New World Tyto

furcata as a separate species from the Old World taxa. Work that might

refine understanding of the Barn Owl complex both within the New World and

separately in the Old World is discussed along with what is known about vocal

and plumage differences. Genetic data presented in the previous proposals are

included for the sake of completeness.

The

cosmopolitan Barn Owl (Tyto alba) has a long and complex taxonomic

history, with the American, African, southeast Asian, Australian, and many

insular taxa being considered full species at various points. The current AOS

taxonomy (AOU 1998) is largely based on Peters (1940) who lumped many

previously recognized species under a cosmopolitan Tyto alba, with 34

then-recognized subspecies. When the AOU expanded coverage to include the West

Indies and Middle America, T. glaucops (previously subsumed under T. alba

by Peters 1940) was recognized as a separate species given its sympatry with T.

a. pratincola (AOU 1983). More recently, some authors have opted to

consider the American furcata clade and the southeast Asian + Australian

javanica clade as two species separate from the alba clade of

Europe and Africa (e.g., Gill et al. 2024). Additionally, three insular taxa from

the Macaronesian islands are occasionally elevated to species level (Robb

2015), as are some insular taxa in the Indian Ocean and Indonesia. Many of

these insular taxa are much darker than their mainland counterparts, including

some with dark facial disks. These are all outside our area but highlight that

species limits in the complex are highly dynamic, and that insular taxa

especially are treated as full species by some authors.

For

reference pertinent to this proposal, select taxa and subspecies groups

(based on Clements 2023) along with their respective distributions are listed

below:

• alba (Scopoli, 1769).

Subspecies group (4 taxa) Europe, n. Africa, and Middle East east to Iran

(hereafter alba ssp. group); the alba clade as a whole includes

the alba ssp. group plus six other subspecies that occur on islands off

Africa (5 taxa) and across sub-Saharan Africa (1 taxon, T. a. poensis),

each regarded as a separate subspecies group by Clements (2023).

• javanica (Gmelin, 1788).

Subspecies group (6 taxa) Pakistan east across s. Asia to Australia; also

referred to as javanica clade.

• furcata (Temminck, 1827). In sensu

stricto (s.s.) refers to T. a. furcata, a monotypic

subspecies group, White-winged Barn Owl (Clements 2023), of Cuba, Isle of

Pines, Cayman Islands, and Jamaica; elevated to species rank based on osteological differences by Suárez and Olson (2020);

sometimes regarded as part of tuidara subspecies group. For this

proposal, furcata clade or simply furcata refers to all 11

subspecies in the Americas, including tuidara group, currently

classified under T. alba (sensu lato, s.l.) and proposed

to be split as T. furcata.

• tuidara (J. E. Gray, 1827)*.

Subspecies group (6 taxa) ranges from Canada to Tierra del Fuego. Type locality

of tuidara is Brazil. [* see footnote on publication year]

• punctatissima (Gould & G. R.

Gray, 1838). Galápagos.

• pratincola (Bonaparte, 1838).

Mainland North America south to southern Mexico, recently to Hispaniola. Part

of the tuidara subspecies group.

• glaucops (Kaup, 1852)*.

Hispaniola. [* see footnote on publication year]

• insularis (Pelzeln, 1872). St.

Vincent south to Grenada. With nigrescens grouped as Lesser Antilles

Barn Owl (Clements 2023) or as a species (Suárez and Olson 2020); regarded as

subspecies of T. glaucops by Bruce (1999) and Gill et al. (2024).

• nigrescens (Lawrence, 1878).

Dominica. With insularis grouped as Lesser Antilles Barn Owl (Clements

2023) or as a subspecies under insularis (Suárez and Olson 2020);

regarded as subspecies of T. glaucops by Bruce (1999) and Gill et al.

(2024).

New

information:

Vocalizations:

One

of the primary issues raised by committee members in previous proposals is the

lack of analysis of vocalizations in the Barn Owl complex. Although no formal

analysis is yet published, we think that the qualitative analysis provided here

is sufficient to elevate the furcata clade to species rank. Across the

genus Tyto and within the Barn Owl complex there are a wide array of

both vocal and mechanical sounds. Here we focus on the context of vocalizations

associated with breeding, which is also the time when these owls are most

vocal. Two specific types of vocalizations are defined below: Screech

and kleak-kleak.

•

Screech: Categorized as either courtship or perennial (Robb 2015).

Recordings below are from https://soundapproach.co.uk/species/common-barn-owl/

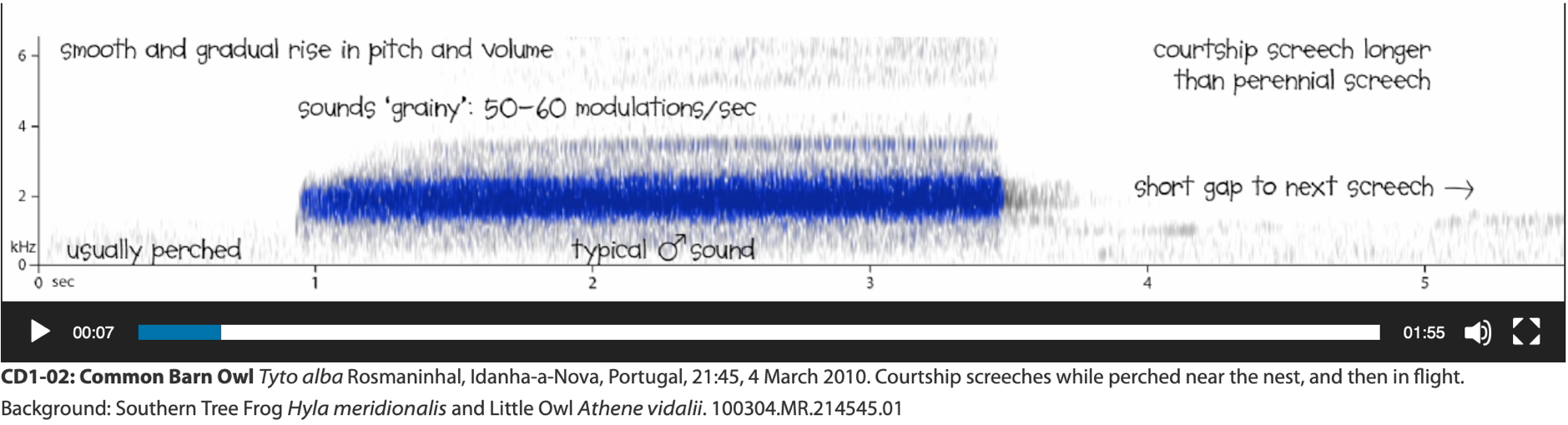

(1) Courtship screech:

Used by males of alba clade (here specifically alba ssp. group), typically

given when perched but also in flight. Courtship screech in addition to

perched context is also longer and with shorter gaps between calls compared to

the perennial screech. Existence and context of this courtship screech is

unknown in the furcata clade (G. Vyn fide Robb 2015). Notably,

none of us has ever experienced a bird of the furcata clade screech from

a perch. This needs further investigation.

Spectrogram of courtship screech

by T. a. alba (Robb 2015)

(2) Perennial screech: Used by both sexes, uttered in

flight and less often from perch in alba clade but perhaps

never (or rarely?) given from perch in furcata clade. Further

investigation between the perennial screech of the alba clade and the flight calls of the furcata clade is needed, especially in the

context of whether the call is uttered when flying or perched.

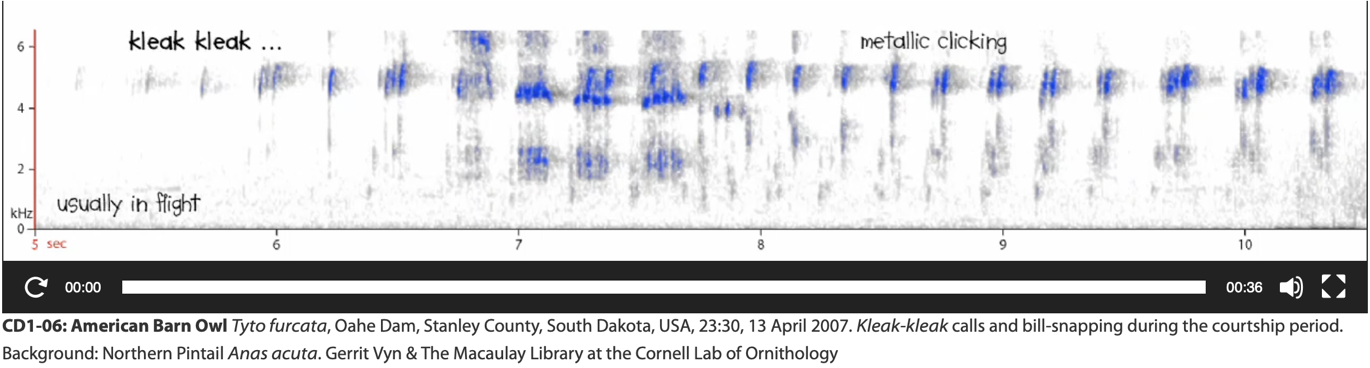

• kleak-kleak (Vyn 2006): Given

in flight by furcata clade, perhaps most

often used by unpaired males (Gerrit Vyn pers comm fide M. Robb) or males in vicinity of

nest (Marti et al. 2020); presumed to have an important role in mate

attraction. Absent in both alba and javanica clades. Sometimes

categorized under terms like cackles, chirrups, or twitters.

Spectrogram of kleak-kleak by T. a. pratincola (Vyn 2006)

The

screech (or scream in Marti et al. 2020) is the best-known

vocalization. The kleak-kleak call was described under “chirrups and

twitters” in Marti et al. (2020). We note that much published information

on vocalizations draws on Old World studies. Thus, it is important to heed the

warning in Marti et al. (2020):

“Other than anecdotal

notes, only unpublished information is available on vocalizations by the North

American race (E. McLean and B. Colvin pers. comm.). Some of the calls

described […] have not been positively documented for the North American race.”

Indeed,

much of the behavioral context and sounds ascribed to Barn Owls in the Americas

is adopted from Old World literature. Our summary here is guided in large part

by “The Sound Approach” (Robb

2015), with especially helpful material published by that author on Barn Owls

of the alba ssp. group here. One of us (O.J.)

perused the sonograms of all available Old World recordings on Xeno-canto

(1,080 alba clade and 62 javanica clade), plus a large selection in

the Macaulay Library. We found no examples

of kleak-kleak in either alba or javanica clades.

From

listening to recordings of many Tyto species, including glaucops

and various Masked/Grass owls it is clear that the loud screech call is fairly

conserved across the genus. There is some variation in length of the call among

species, and some have a whistled quality, but there is also much intra-taxon

variation in call length, perhaps related to whether these are courtship or

territorial, perennial screeches.

Typical

screech calls of the three clades are given below. For javanica and alba

clades, the screech tends to fade out and fall in pitch at the end of the

calls, unlike furcata clade which ends more abruptly and rises slightly

at the end:

alba: https://macaulaylibrary.org/asset/301733691

javanica: https://macaulaylibrary.org/asset/117266311 and https://macaulaylibrary.org/asset/271631421

furcata: https://macaulaylibrary.org/asset/50147

European

birds (alba) do tend to give longer screech calls than furcata,

while javanica are generally shorter but with a subtly different quality

than furcata. However, alba and javanica commonly have a

harsh whistled quality to the notes:

alba: https://macaulaylibrary.org/asset/235237551 and

https://macaulaylibrary.org/asset/367445881

javanica: https://macaulaylibrary.org/asset/273379781

Here

is an exceptionally long screech call from furcata: https://macaulaylibrary.org/asset/425012341

Non-screech

calls, when present, seem quite different among species. The Australian

Masked-Owl (T. novaehollandiae) utters a call

called a cackle that is said to be given in

courtship display flights by males circling over breeding territory (Higgins

1999, page 919). An example of that cackle call is here (https://macaulaylibrary.org/asset/539506871) and seems analogous

to the kleak-kleak call of furcata.

Likewise, analogous vocalizations exist in the two grass owls, T. capensis and T. longimembris

(Robb 2015).

The

kleak-kleak call of furcata is present across its range, with

recordings from California, Florida, and Brazil. Here are a few examples:

https://macaulaylibrary.org/asset/172455681

https://macaulaylibrary.org/asset/245778421

https://macaulaylibrary.org/asset/554918181

Critically,

this “kleak” call appears to be entirely absent

from both alba and javanica according

to The Sound Approach and our own perusal of

recordings. Robb (2015), quoting Gerrit Vyn (pers. comm.), says that “unpaired

males use this call most often…so it must have an important role in mate

attraction.” Marti et al. (2020) also report that males give the “kleak” call in the vicinity of the nest, soon after

leaving the daytime roost, and when approaching with food deliveries. Given

that analogous calls exist in T. novaehollandiae

and other Tyto, we suspect it has been lost in alba and javanica. Regardless, in our view this is a diagnostic vocal difference

between the clades.

In our personal experience, this “kleak” call is nearly always given in flight. For example, JLD recently witnessed (summer 2023) one bird giving the kleak-kleak call in fluttery flight almost nonstop for a few minutes as it circled a lit up area near a known nest. The only mention that we can find regarding the “kleak” call for alba is Bunn et al. (1982), who say that it is reportedly uncommon in Britain. This contradicts Robb (2015) who has extensive experience with the alba ssp. group in Portugal and elsewhere. Despite fairly exhaustive searches of databases online we are unable to find any recordings of this vocalization from anywhere in the Old World. This reference of the kleak call in Britain appears anecdotal and could refer to another call that Bunn (1977) called the kit-kit call.

We

feel it worth mentioning that no North American Field Guide or popular book on

owls, including König et al. (1999) and Weidensaul

(2015), mention the kleak-kleak call or its context in display. How did

the birding community miss this characteristic sound of New World birds? The

one source that does have it is Marti (1992), but none of us picked this up.

Genetics:

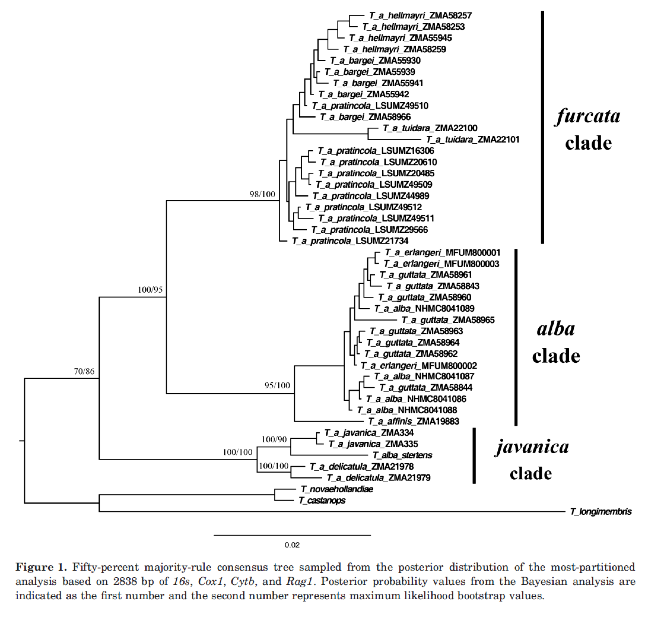

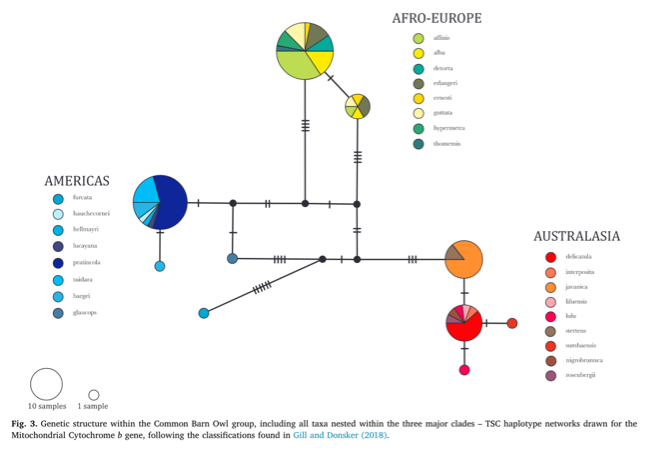

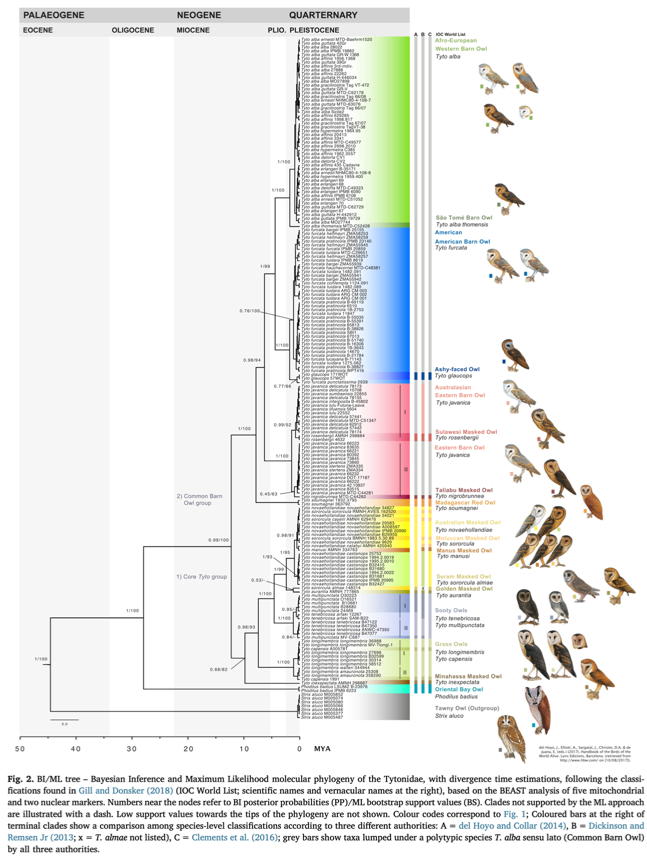

A

paper by Uva et al. (2018) analyzed two nuclear and five mitochondrial loci to

estimate a phylogeny of Tytonidae. This paper was included in the 2018-C-13

NACC proposal, and the proposal included a haplotype map that was based on a

single mitochondrial gene but did not include the phylogeny that was based on a

greater set of genes. That proposal did include the phylogeny from earlier work

by Alibadian et al. (2016) that was based on slightly fewer genes and many

fewer taxa. Although comments from many committee members considered the

genetic evidence inconclusive on its own, we include it in the current proposal

for the sake of completeness. Relevant figures from Alibadian et al. (2016) and

Uva et al. (2018) are reproduced below.

Phylogeny

from Alibadian et al. (2016):

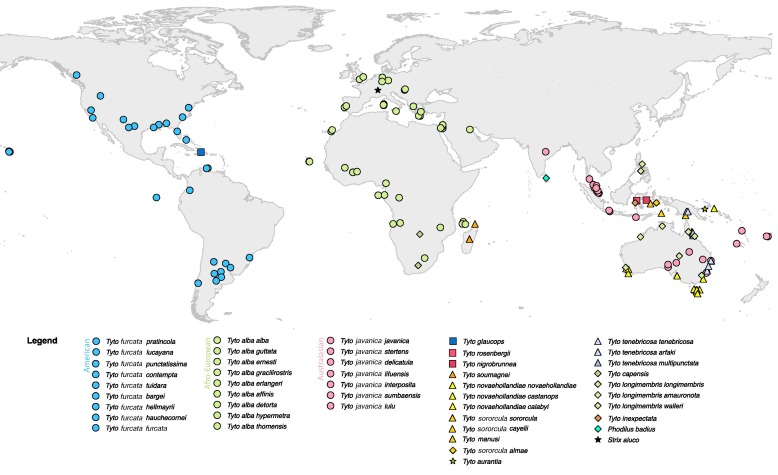

Sampling

map, haplotype network, and phylogeny from Uva et al. (2018):

Based

on the genetic data, the current circumscription of Tyto alba comprises

three major clades: alba, furcata, and javanica, with the former

two being sisters. Uva et al. (2018) advocated elevating both furcata

and javanica to species rank. Whether the alba and javanica

clades should be treated as species is outside our purview and perhaps should

await potential future contact (see Additional Considerations, below).

A

few issues arise. First, Tyto glaucops is embedded within the furcata

clade, being sister to punctatissima of the Galápagos, the two in turn

being sister to the rest of the furcata clade. However, Uva et al.

(2018) note that “given the poor node support (0.77 PP/66 BS) putative genetic

distinctiveness of Caribbean and Pacific populations needs further

confirmation” and we agree with that assessment. Regardless, the species status

of punctatissima should be left to SACC.

Another

issue is that two dark taxa of the Lesser Antilles, nigrescens and insularis,

were not sampled by Uva et al. (2018); these taxa have been considered as

subspecies of Tyto glaucops or as their own polytypic species (Suárez

and Olson 2020). Given the lack of genetic and vocal information on these taxa,

we think it best to leave them as subspecies of alba (or furcata

if this proposal is adopted) for now, pending further study. Also see

Additional Considerations, below, regarding anecdotal information on Barn Owl

calls heard on Grenada where insularis occurs.

A

recent paper on Barn Owls of the West Indies by Suárez and Olson (2020) was the

basis for NACC proposal 2022-B-6, which did not pass but focused on the species

status of glaucops, nigrescens, and insularis plus some extinct

forms. Suárez and Olson (2020) analyzed osteological data from extinct and

extant Caribbean Tyto. They elevated the taxon T. a. furcata

Temminck 1827 of Cuba, the Cayman Islands, and Jamaica to species rank, leaving

tuidara J. E. Gray 1827 as the name for the American mainland species.

However, their osteological comparisons were to alba of Europe rather

than to pratincola of the United States, so the question of species rank

for furcata s.s. is unresolved. With regard to the priority of furcata

for American Barn Owls over tuidara if split from alba, see

footnote establishing that furcata has priority. Also note that furcata

s.s. is considered a separate subspecies group by Clements (2023) based

on the paler white plumage, especially of the wings. If, in the future, furcata

s.s. is elevated to species rank, then the name for the remaining

American barn owls would be tuidara Gray 1827. We note that Uva et al.

(2018) sampled one individual that they labeled as furcata s.s. (sample

number IPMB 20859), but no list of detailed sample localities is given in the

paper or supplementary data and there is no dot from Cuba, Jamaica, or the

Cayman Islands (the distribution of furcata) on their sampling map;

moreover, we do not recognize the museum acronym and were unable to find a

relevant record on VertNet or GBIF. Thus, it is unclear to us if true furcata

was sampled by Uva et al. (2018). Although it would be the nominate taxon of

the American clade, we think it extremely unlikely that it would be more

closely related to Old World taxa than to mainland North American taxa, so it

should not affect the separation of furcata clade from alba + javanica

clades. It may have implications for the taxonomy of other Caribbean Tyto,

however, if those are elevated to species rank in the future.

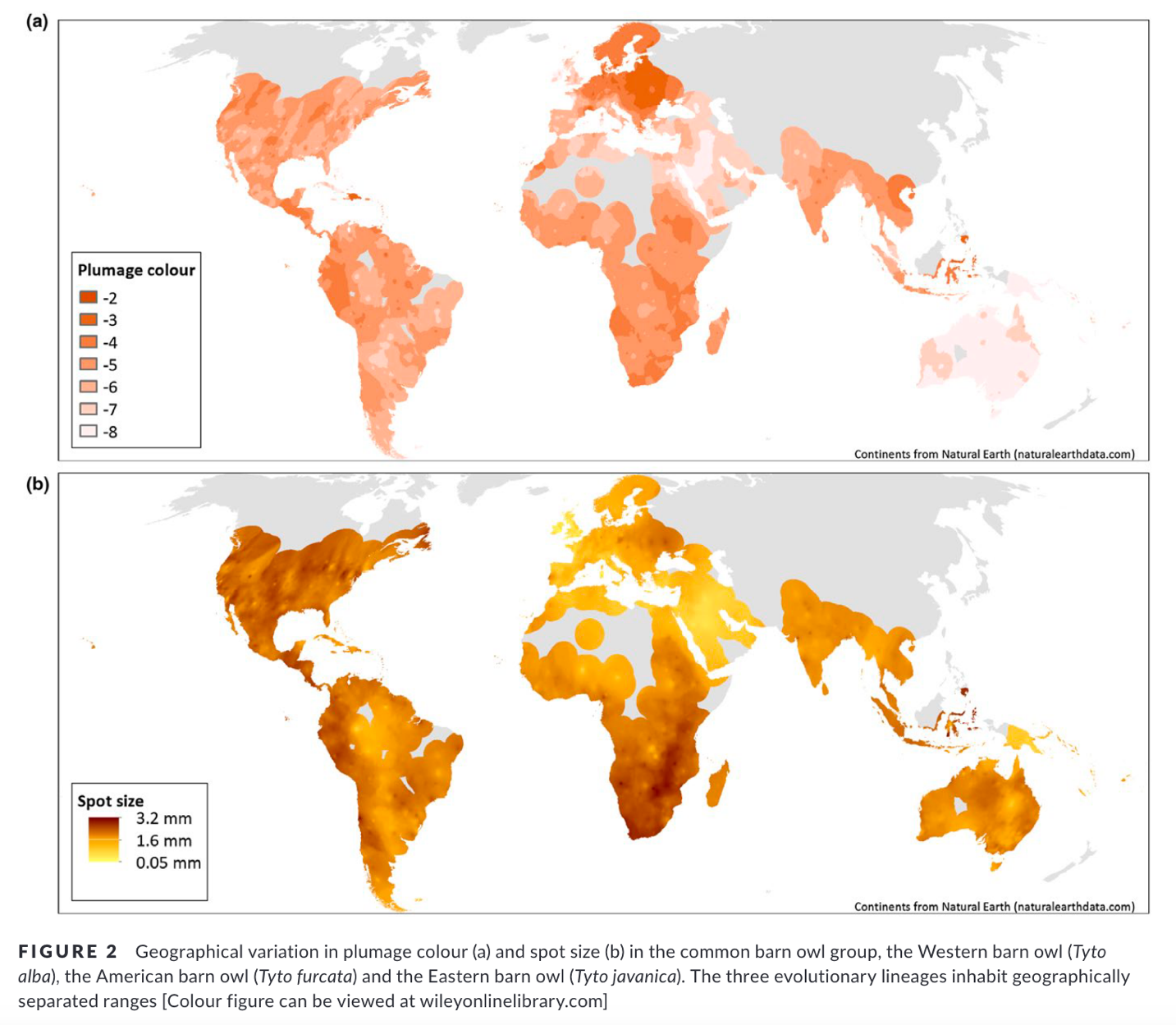

Plumage coloration:

Romano et al. (2019, Figure 2 reproduced here)

showed that plumage coloration appears closely tied to rainfall and

temperature. As can be seen in their maps, overall plumage coloration and spot

size are not drastically different between the three clades (furcata,

alba, and javanica).

Nevertheless, the plumage and size of several taxa within the Americas do

appear quite distinctive, e.g. punctatissima of

the Galápagos, bargei of Curaçao, and insularis/nigrescens of

the Lesser Antilles. Indeed, Ridgway (1914) separated these taxa and glaucops

from furcata s.s. and the remaining mainland American Barn Owl

taxa based on non-overlapping size, among other characters. Although not part

of this proposal, we would not be surprised if more detailed studies suggest

splitting more of these insular New World taxa. Interestingly, Ridgway (1914)

noted that bargei is similar to nominate alba of Europe in

coloration but is much smaller. We note that Uva et al. (2018) sampled bargei

and found it nested within the furcata clade.

Additional

considerations:

We currently consider Tyto

glaucops unambiguously a separate species from T. alba s.l. based on

sympatry on Hispaniola. Earlier authors, however, considered glaucops

conspecific with alba s.l. (e.g., Hartert 1929, Peters 1940). On

Hispaniola, T. alba either colonized sometime after 1930 or was

overlooked before that (Keith et al. 2003). The source population is thought

likely to have been pratincola from the mainland or Bahamas (Marti et

al. 2020). Species limits considered by earlier authors were based on the same

issues that we are dealing with currently, namely plumage and vocalization

differences (but now also genetic) among allopatric insular populations.

However, once colonization by alba s.l. occurred, it became clear that glaucops

and alba s.l. were distinct species, a treatment followed ever since.

We

listened to available recordings of glaucops (of which there are few,

see examples below) and were not struck by major differences from furcata,

which raises additional questions. If furcata and glaucops are

sympatric, how are these being maintained as separate species despite the lack

of described vocal differences? The screech call of glaucops seems a bit

longer and more descending compared to furcata, which is interesting. If

that is the case, then there are some minor vocal differences in the

screech. A similar kleak call to the furcata clade is uttered by glaucops

and could be taken as further evidence that this is a major character

separating all New World barn owls (broadly speaking) from Old World barn owls.

This, then, would be more evidence for splitting furcata. On the other

hand, if plumage differences are keeping glaucops and furcata

separate, how does that fit into our understanding of species limits in the

genus given that plumage seems to covary with all sorts of things not related

to species limits? Maybe the fast evolution of plumage in the genus allows for

occasional evolution of drastically different-looking species?

Here

is an example of the cackling kleak call by glaucops:

https://macaulaylibrary.org/asset/175146681

And

recordings of its screech:

https://macaulaylibrary.org/asset/163149861

https://macaulaylibrary.org/asset/180725

We

note in passing that Alvaro Jaramillo suggested that Barn Owls Grenada (insularis)

gave vocalizations “much more like Ashy-faced Owl than Barn Owl” (Norton et al.

2005, page 512). Jaramillo’s analysis is repeated by Wiley (2021, page 209),

who himself reviews the taxonomic history of Barn Owls in the eastern Greater

Antilles through the Lesser Antilles. Note that east and south of glaucops

on Hispaniola (and formerly Puerto Rico; Suárez and Olson 2020), Barn Owls

occur on Dominica (nigrescens) and then on St. Vincent, some islands in

the Grenadines, and south to Grenada (insularis), with no confirmed

records for intervening Martinique and St. Lucia (Wiley 2021). To our ears, the

calls of T. glaucops do not sound that different from the furcata

clade so opining about calls of insularis on Grenada might be difficult

without careful analysis. Some recordings of insularis sound similar to

vocalizations of mainland furcata (https://macaulaylibrary.org/asset/541151851) but

others do sound quite different and rather like some recordings of alba s.s.

(https://macaulaylibrary.org/asset/317964701).

Given

that the node separating glaucops/punctatissima from furcata

is 1.75 Ma (Uva et al. 2018), it seems to us a reasonable yardstick extension

to consider the much older splits of alba and javanica as

different species from furcata (javanica vs. alba/furcata

is 6.25 Ma, alba vs. furcata is 4.35 Ma). The alternative here is

that glaucops/punctatissima are a recent offshoot from furcata that

(unambiguously in glaucops) evolved reproductive isolation, while furcata

and alba have not. We think that this is unlikely given that glaucops

seems to have evolved reproductive isolation despite limited or no differences

in vocalizations, while the limited vocal data we have indicate very distinct

vocalizations between furcata and alba + javanica (primarily the

lack of a “kleak” call in the latter as well as existence of courtship

screech in at least alba ssp. group in alba clade). We also note

that the node uniting glaucops and punctatissima has lower

support (0.77 posterior probability/66% bootstrap) than most other nodes in

that part of the tree, so the furcata clade may not be paraphyletic with

broader genomic sampling. The node separating glaucops and punctatissima

is 0.44 Ma. Uva et al. (2018) did not provide confidence intervals on these

node date estimates.

There

is also limited evidence that at least furcata and javanica are

reproductively isolated. Populations from each of those clades were introduced

onto Lord Howe Island to control rats: T. a. delicatula from the

Australian mainland in 1923, and T. a. pratincola from the San Diego Zoo

in 1927 (Hindwood 1940). Birds from these two taxa were not known to

interbreed, and this was taken as evidence that the two should not be

considered the same species (Bruce 1999). The only Barn Owl specimens collected

from Lord Howe are of the Australian population, and no Barn Owls are known to

have persisted past the mid 1980s (McAllan et al. 2004). It is presumed the

American birds died out soon after introduction. This contact between the javanica

and furcata clades could suggest that assortative mating was taking

place, but the period of sympatry was brief compared to the longer period of

sympatry between pratincola and T. glaucops on Hispaniola. We do

note that javanica is the more distant clade in the phylogeny and does

not provide direct evidence of species rank for the alba clade versus

the furcata clade. However, it does suggest that multiple species exist

within the cosmopolitan Barn Owl.

Finally, the International

Ornithologists’ Union Working Group on Avian Checklists (WGAC) has recently

split Barn Owl into three species, elevating the javanica and alba clades

in addition to furcata. Although recognizing two Old World species is

outside our purview, support for this is based on morphological differences (Dick Schodde fide

T. Chesser) and genetic evidence showing that the javanica and alba

clades are not sisters (Uva at al. 2018). It is important to note, however,

that Barn Owls have expanded east across much of Iran starting in the 1990s

(Osaei et al. 2007). Prior to this, when the species was rare in Iran,

specimens were ascribed to T. a. erlangeri of the alba

clade (Vaurie 1965). The easternmost record in Iran (subspecies unknown) is at

Bam, Kerman Province (Osaei et al. 2007), which is 900 kilometers (560 miles)

west of the western limit of T. a. stertens of the javanica

clade on the Indus Plain, eastern Pakistan. Thus, future contact between javanica

and alba is possible, and further research would help to elucidate

whether reproductive isolating mechanisms such as vocalizations exist to

maintain species-level differences. Nevertheless, we think it is worth

separately considering elevating javanica to species rank to align with

this global checklist.

Recommendation:

We

recommend splitting Tyto alba (Scopoli, 1769)

into at least two species to recognize the vocal and genetic distinctiveness of

New World taxa as American Barn Owl, Tyto furcata

(Temminck, 1827). If the javanica and alba clades are considered conspecific, then Common

Barn Owl is typically used for the Old World taxa.

English names: American Barn Owl is in wide usage

by authorities that split furcata from alba, and we recommend

that it be adopted. American Barn Owl was used by Ridgway (1914) for pratincola.

Because of the possibility of paraphyly with glaucops and various other

taxa embedded within javanica, we think that “Barn Owl” should not be

hyphenated unless there is interest in renaming glaucops to “Ashy-faced

Barn-Owl”. “American” in this context refers to the two continents on which

this species occurs.

If the javanica and alba

clades are retained as conspecific, then Common Barn Owl is typically used for

the Old World taxa. However, the IOC (Gill et al. 2024) recognizes javanica

and alba as Eastern Barn Owl and Western Barn Owl, respectively.

Clements (2023) uses Eastern Barn Owl, Eurasian Barn Owl, and American Barn Owl

for the subspecies groups. These English names are not ideal and potentially

misleading (e.g. “Eurasian” occurs in Africa, and “Eastern” and “Western” could

be confused with eastern and western North America). Therefore, consideration

or solicitation of alternative names for the Old World taxa is merited.

Acknowledgments

and Footnotes:

David

Donsker helped research publication dates for relevant taxa. Alan Peterson’s

Zoonomen.net website provided notes and insights on the publication dates of

original descriptions.

* tuidara (J. E. Gray, 1827): This name was published at

earliest 1 December 1827. Gill et al. (2024), among others, use 1828, whereas

Bruce (1999) and Peters (1940), for example, use 1829. The name Tuidara Owl

of John Edward Gray appeared in part 14 of Griffith’s Animal Kingdom, and this

part was published 1 December 1827 (see table here).

Temminck’s “Strix furcata”

was published 30 June 1827 in livraison 73, plate 432 of the “Nouveau

recueil de planches coloriées” (see table here

and would therefore have priority regardless of the confusing dates ascribed to

tuidara. The date of 1827 was

used for tuidara

by Suárez and Olson (2020), presumably based Cowan (1969). We use it here for

the same reason.

* glaucops

(Kaup, 1852): We found conflicting dates for this publication. The fourth

edition of Howard and Moore checklist (Dickinson and Remsen 2013), Bruce

(1999), and AOU (1998) use 1853. Gill et al. (2024), Peters (1940), and older

publications use 1852. Note that Murray Bruce later agreed 1852 is the correct

date (see notes here).

Literature

cited:

Alibadian M., N.

Alaei-Kakhki, O. Mirshamsi, V. Nijman, and A. Roulin. (2016). Phylogeny,

biogeography, and diversification of barn owls (Aves: Strigiformes). Biological

Journal of the Linnean Society 119, 904–918.

American Ornithologists' Union. (1983). Check-list of

North American birds. 6th ed. Am. Ornithol. Union, Washington, D.C.

American Ornithologists' Union. (1998). Check-list of North American birds. 7th edition. Washington, D.C.: American Ornithologists' Union.

Bruce, M.D. (1999).

Family Tytonidae (Barn-owls. In Handbook of the Birds of the World, Vol. 5),

pp. 34–75 (J. del Hoyo, A. Elliott, and J. Sargatal, Editors). Lynx Editions,

Barcelona.

Bunn, D. S. (1977).

[Letters] The voice of the Barn Owl. British Birds 70(4):171.

Clements,

J. F., P. C. Rasmussen, T. S. Schulenberg, M. J. Iliff, T. A. Fredericks, J. A.

Gerbracht, D. Lepage, A. Spencer, S. M. Billerman,

B. L. Sullivan, and C. L. Wood. (2023). The eBird/Clements checklist of Birds

of the World: v2023.

Cowan, C.F. (1969).

Notes on Griffith's Animal Kingdom of Cuvier (1824-1835). Journal of the

Society for the Bibliography of Natural History 5:137–140.

Gill, F., D. Donsker, and P. Rasmussen (Eds). (2024). IOC

World Bird List (v 14.1). doi 10.14344/IOC.ML.14.1

Hartert,

E. (1929). On various forms of the genus Tyto.

Novitates Zoologicae 35:93–104.

Higgins,

P., Ed. (1999). Handbook of Australian, New Zealand and Antarctic Birds. Volume

4. Parrots to Dollarbird. Oxford University Press, Melbourne, Australia.

Hindwood,

K. A. The birds of Lord Howe Island. Emu 40:1–86.

Keith, A. R., J. W. Wiley, S. C. Latta and J. A. Ottenwalder. (2003). The

Birds of Hispaniola: Haiti and the Dominican Republic. British Ornithologists’

Union Check-list No. 21. The Natural History Museum, Tring.

König,

C., F. Weick, and J.-H. Becking (1999). Owls. A Guide to the Owls of the World.

Pica Press, Robertsbridge, UK.

Marti, C. D. (1992). Barn Owl. In The Birds of North America, No. 1 (A. Poole, P. Stettenheim, and F. Gill, Eds.). The Academy of Natural Sciences, Philadelphia; The American Ornithologists' Union, Washington D.C. https://doi.org/10.2173/tbna.1.p

Marti, C. D., A. F.

Poole, L. R. Bevier, M.D. Bruce, D. A. Christie, G. M. Kirwan, and J. S. Marks

(2020). Barn Owl (Tyto alba), version 1.0. In

Birds of the World (S. M. Billerman, Editor). Cornell Lab of Ornithology,

Ithaca, NY, USA. https://doi.org/10.2173/bow.brnowl.01

McAllan,

I. A. W., B. R. Curtis, I. Hutton, and R. M. Cooper. (2004). The birds of the

Lord Howe Island group: a review of records. Australian Field Ornithology 21

(Supplement) 1–82.

Norton,

R. L., A. White, and A. Dobson. (2005). The Spring Migration: West Indies &

Bermuda Region. North American Birds

59(3):511–513.

Osaei, A., A.

Khaleghizadeh, and M. E. Sehhatisabet. (2007). Range extension of the Barn Owl Tyto

alba in Iran. Podoces 2(2):106–112.

Peters, J. L. (1940).

Check-list of the birds of the world. Volume IV. Harvard University Press,

Cambridge, Mass.

Ridgway, R. (1914).

Birds of North and Middle America. Bulletin of the United States National

Museum 50, part VI.

Robb,

M. & The Sound Approach. (2015). Undiscovered owls, A Sound Approach guide.

The Sound Approach. (web version available here:

https://soundapproach.co.uk/undiscovered-owls-web-book/)

Romano, A., R. Séchaud, A. H. Hirzel, and A. Roulin. (2019). Climate‐driven convergent evolution of plumage colour in a cosmopolitan bird. Global Ecology and Biogeography 28:496–507.

Suárez, W., and S. L.

Olson. (2020). Systematics and distribution of the living and fossil small barn

owls of the West Indies (Aves: Strigiformes). Zootaxa 4830:544–564.

https://doi.org/10.11646/zootaxa.4830.3.4

Uva V., M. Päckert, A.

Cibois, L. Fumagalli, and A. Roulin. (2018). Comprehensive molecular phylogeny

of barn owls and relatives (Family: Tytonidae), and their six major Pleistocene

radiations. Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 125 (2018):127–137. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ympev.2018.03.013

Weidensaul, S. (2015).

Peterson Reference Guide to Owls of North America and the Caribbean. Houghton

Mifflin Harcourt, Boston.

Wiley,

J. W. (2021). The Birds of St Vincent, the Grenadines and Grenada. British

Ornithologists’

Club Checklist Series, volume 27.

Vaurie, C. 1965. The birds of the Palearctic fauna: a systematic

reference non-Passeriformes. H. F. & G. Whitherby, London.

Vyn, G. (2006). Voices of North American owls. 2 CD’s and booklet. Ithaca.

Louis Bevier, Carla

Cicero, Jon L. Dunn, Rosa Alicia Jiménez, and Oscar Johnson

February 2024

Comments

from Jaramillo:

“YES to this proposal. I have been listening to and recording

a few Barn Owls over my house recently, and had the same general thought. How

could we have missed that the clicking call is the important vocalization in

reproductively related display, not the screech. I have been listening to a

pair over my house that sometimes displays overhead and actually seem to have

an aerial "dance" of sorts where they cartwheel over each other,

although it is hard to see as it is pretty dark even with the town lights. But

the birds are clicking at each other, and sometimes one of them screeches, but

the clicking call is the key.

“Regarding Ashy-faced, Lesser Antillean and Galapagos birds. The

possible genetic relationship between Galapagos and Antillean birds is not

surprising to me. This pattern happens over and over again in multiple taxa.

There is a Galapagos-Caribbean connection that has not been studied. Galapagos

mockers are sister to Bahama Mockingbird, Galapagos finches are sister to the

mainly Caribbean closed nest tanager radiation (the "quits"), even

the flamingo is a connection. I worked with a Cuban spider expert who mentioned

that Cuban spiders had some relatives in Galapagos. The fact that this has not

been looked at more closely is interesting to me. I assume that there are some

islands that are gone that connected the two before the Panama land bridge

closed. In any case, I bet that in the future there is a confirmation of an

Antillean/Galapagos Barn Owl clade.”

Comments from Robbins: “YES. What an in-depth proposal!

Kudos to Bevier et al. for the extensive perspective on this. Their proposal along with Alvaro's comments

about the clicking call seem to underscore the importance of that vocalization:

present in New World and apparently absent in Old World taxa. That coupled with

the genetic data support recognizing New World furcata as a separate

species from Old World alba. I vote yes in support of this split.”

Comment from Andrew Spencer: “Pieplow

(2017) does mention the voc (which he calls "chitter") and does say

it can be given by pairs in courtship.”

Comments

from Niels Krabbe (voting for Elisa Bonaccorso): “YES. Back in the

late 1960s I banded a brood of three Barn Owl chicks and had the luck to have

all three recovered. One had flown 10 km SW, another 150 km N, and the third

over 100 km E. Even though adult Barn Owls can be among the most resident birds

and spend their entire life inside a single barn, young birds have a great

capacity for dispersal, so I was fine with its worldwide distribution. As much

as I hate to see another cosmopolitan go (there seems to be only Peregrine

left), I see from the extensive, primarily mitochondrial comparisons by Uva et

al. (2018) that the division of the Common Barn Owl group into three major

clades is well-supported. The absence of the "kleak-kleak" sound in

both alba and javanica clades and its presumed importance in mate

attraction, as mentioned above, indeed supports species rank for the furcata

clade. I was a bit surprised to find that several Xeno-Canto recordings of

screeches by furcata were of perched birds, but far the most were in

flight. Personally, I have only heard the short perennial screech, and only

from flying birds. I was flabbergasted, when I first experienced a bird flying

back and forth while giving the “kleak-kleak” call, which I had never heard in

Europe.

“The proposal is elaborate and thorough, and I

can find nothing to add. As stated, it is puzzling, that two Tyto

species with quite similar vocalizations are both widespread on Hispaniola

without interbreeding, and, also as stated, it would be interesting to know if

the dark forms nigrescens and insularis (Lesser Antilles), belong

with glaucops or furcata, but this is all outside the scope of

SACC. As also discussed above, the mitochondrial similarity between glaucops

and the Galapagos punctatissima has low support and needs to be

substantiated by in-depth studies.

“I vote YES for ranking American Barn Owl as a

species Tyto furcata.”

Comments

from Areta:

“YES. I was already convinced in https://www.museum.lsu.edu/~Remsen/SACCprop908.htm

that there was overwhelming evidence for this split, and some

unanswered questions on other Tyto. It is not

that the "kleak-kleak" went unnoticed to Neotropical

ornithologists, but it is the lack of it in the Old World that we (or I at

least) were not aware of. Nice proposal, very thorough and clear.”

Comments

from Stiles:

“YES. Genetics and morphology found previously to support this split, but a

thorough study of all available recordings now clearly demonstrates an

important difference in vocalizations that tips the burden of proof onto those

who favor maintaining the single-species status quo.”