Proposal (1000) to South

American Classification Committee

Treat Thamnophilus shumbae as

a separate species from T. bernardi

Note:: This is one of

several situations that the IOU Working Group on Avian Checklists has asked us

to review because published treatments of the species differ, and WGAC has to

pick one. BirdLife International (del

Hoyo & Collar 2014) now treat these two as separate species. I have no first-hand knowledge of this

situation, so my goal here is to lay out as many facts as possible that might

be of potential relevance just to get the discussion started.

Background: As

currently defined (e.g. Dickinson & Christidis 2014), Thamnophilus

(ex-Sakesphorus; see SACC 278) bernardi

consists of two subspecies that show a common pattern of taxon pairs (Tumbesian

+ Marañon):

• T. b.

bernardi Lesson, 1844: sw. Ecuador (Manabí) to nw. Peru (S to Ancash),

including crossing Andes into upper Marañon Valley in Cajamarca (Schulenberg et

al. 2007)

• T. b.

shumbae (Carriker, 1934): Marañon Valley

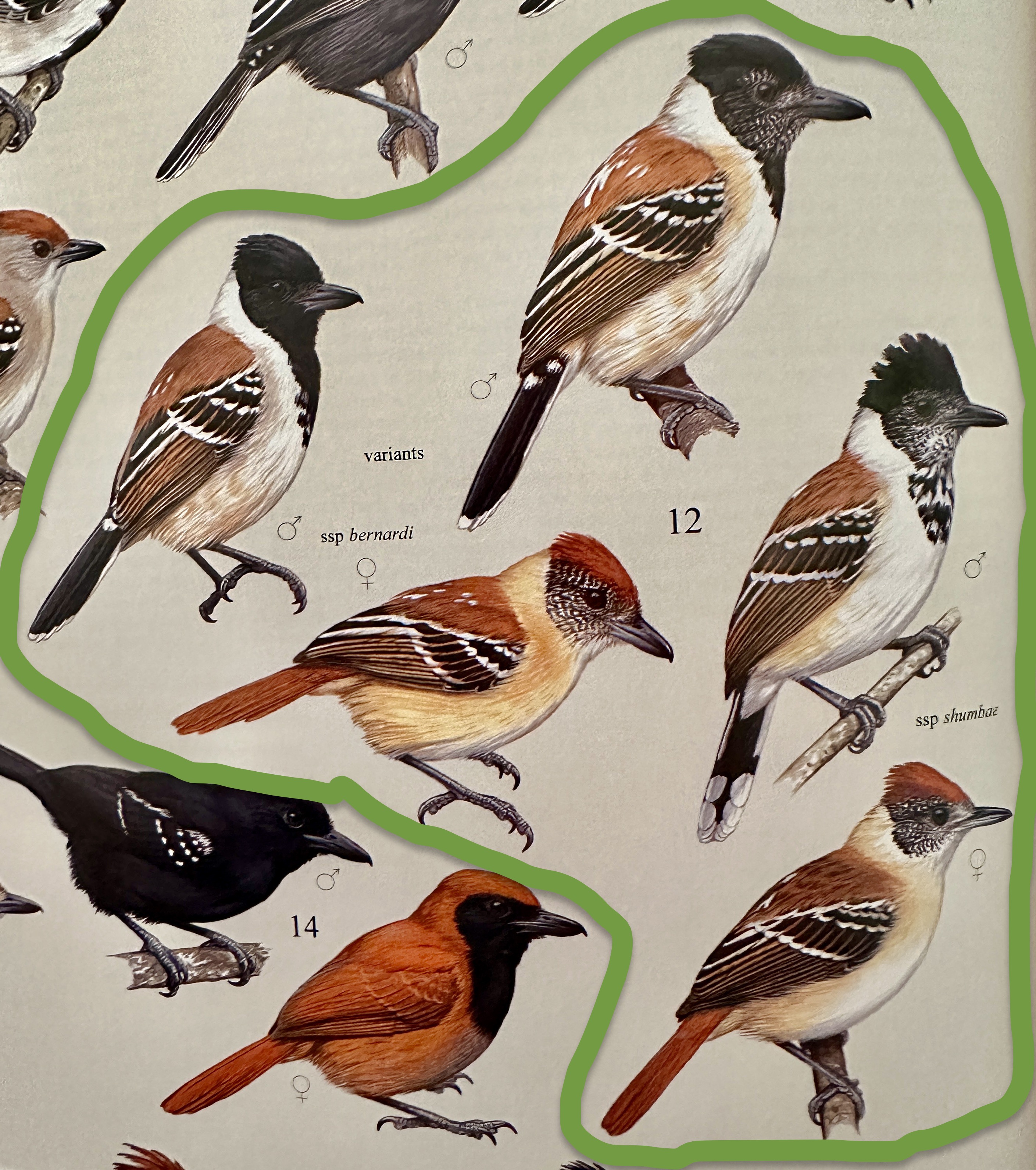

Here

is the terrific plate by Hilary Burn from Zimmer & Isler (2003), here

somewhat desecrated by my green line to show T. bernardi broadly defined. Two extremes of male plumage variation are

shown for bernardi. The female

shown for bernardi has a solid rufous crown, but Zimmer & Isler

noted that some have varying degrees of black in the crown – see also specimen

photos below.

Zimmer

& Isler synonymized two previously described subspecies under nominate bernardi

because their examination of specimens indicated that they were just points on

a cline: piurae Chapman, 1923 (type locality = “Piura”), and cajamarcae

(Hellmayr, 1917; type loc = Tembladera, Cajamarca, 1200 ft.”). The type locality for bernardi is near

the north end of its distribution: Guayaquil.

Another taxon, baroni Hartert and Goodson, 1917 (TL = “Yonan

River, northeast of Trujillo”), was treated as a synonym of cajamarcae

by Cory & Hellmayr (1924) and Zimmer (1933), almost certainly because the

type locality of cajamarcae, Tembladera, is on the Yonán River, and cajamarcae

has priority (barely). Cory &

Hellmayr (1924) and Zimmer (1933) both recognized piurae and cajamarcae. Note that shumbae was described after

publication of Zimmer (1933), who had very few specimens from the Marañon

region.

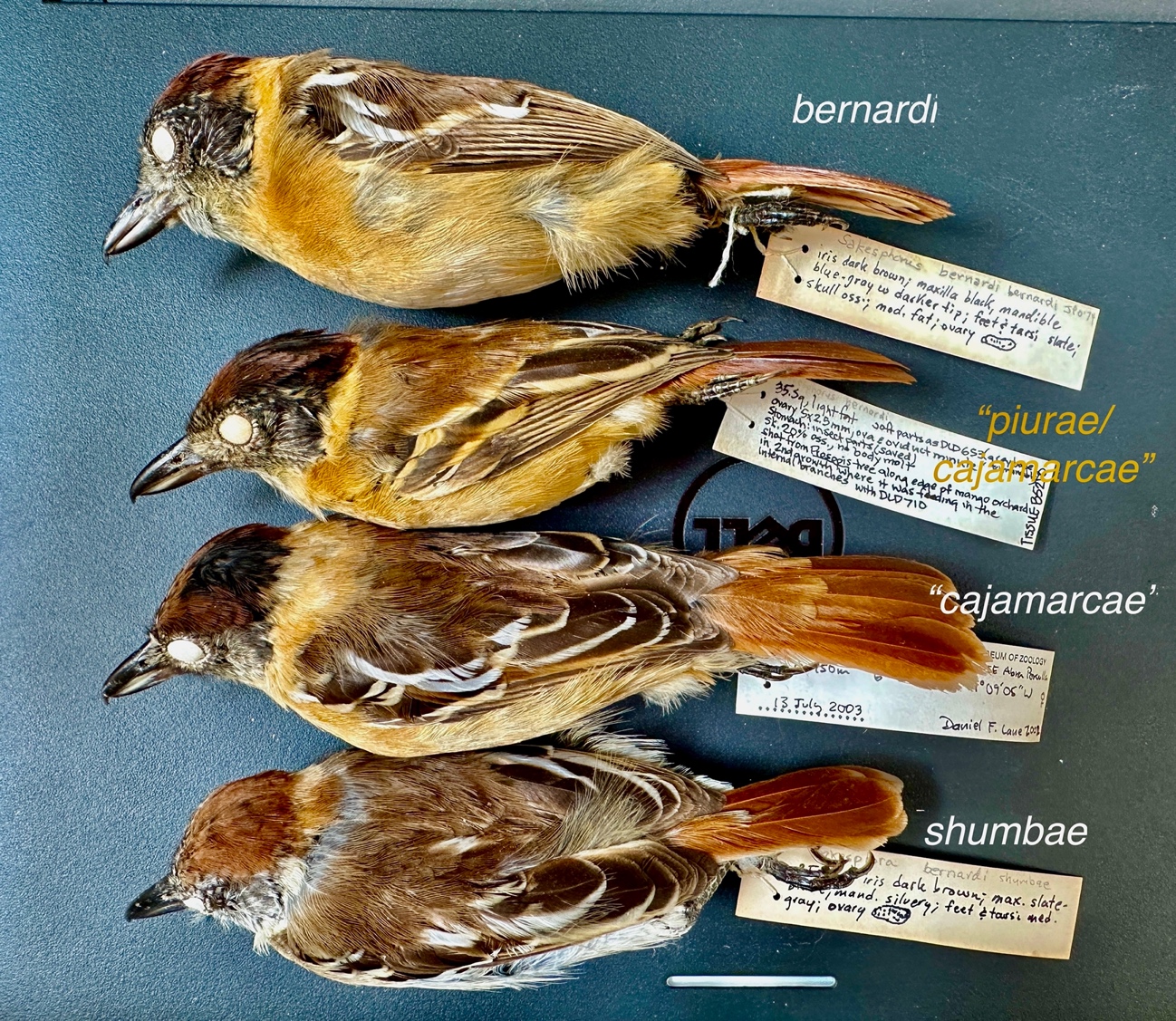

Here are a set of photographs of

specimens of males and females from LSUMNS:

Males (no bernardi

available)

Females

New information:

Schulenberg et al. (2007, Bird of

Peru) noted the song of shumbae differed from bernardi in being

“much faster with distinct introductory and terminal notes” but were evidently

reluctant to make any taxonomic recommendation.

Kevin Zimmer was evidently the first person to notice this (fide

Dan Lane), so I am looking forward to Kevin’s comments especially.

Del Hoyo & Collar (2016)

treated shumbae as a separate species (“Maranon Antshrike”) from bernardi

and other 4 subspecies. Del Hoyo &

Collar’s assessment using the Tobias et al. point scheme is as follows

(courtesy M. Iliff):

“Maranon:

https://birdsoftheworld.org/bow/historic/hbw/colant3/1.0/introduction

Hitherto treated as conspecific with T.

bernardi and placed in Sakesphorus (see T. bernardi), but

differs in its smaller size, notably shorter tail (effect size −3.3; score 2);

buff-tinged whitish vs pale tan-buff underparts in female (2); much reduced black

breast patch in male, so that malar and ear-coverts are black-speckled whitish

rather than black or blackish (2); darker, less rufous dorsal coloration in

male (1); and faster song, with greater pace (2) and shorter note length (2)

(1). Monotypic.”

The vocal differences are based on Boesman (2016), who quantified

substantial differences in pace and note length. Boesman wrote:

“We

can thus conclude that shumbae

has a loudsong which is delivered much faster (score 2-3) and which consists of

much shorter notes (score 2-3). If we include the somewhat faster songs of bernardi when singing in

duet, effect size drops somewhat. Nevertheless, difference still allows for a

score of 2+2 = 4.”

As previously noted, I’m a big fan of Boesman’s notes as catalysts

to guide more thorough research, but he pumped out 457 of these in a short time

and just did not have the time to get them into the shape that would be

required for peer review. In this case,

the geographic distribution of the recordings would have been of interest. No attempt was made to employ directly the

Isler-Whitney scoring system for antbird songs in terms of whether the

different best fit the species or subspecies category.

Some sample recordings:

• bernardi from Guayas,

Ecuador, by John V. Moore: https://xeno-canto.org/258338

• bernardi from Lambayeque,

Peru, by Andrew Spencer: https://xeno-canto.org/45729

• shumbae

from Jaén, Cajamarca, ca. 30 km from type locality of shumbae, by

Fabrice Schmitt: https://xeno-canto.org/543063

• shumbae from Bagua Chica,

Amazonas: https://xeno-canto.org/45701

The differences between the two song types as described by

Schulenberg et al. and Boesman et al. are fairly obvious (to me).

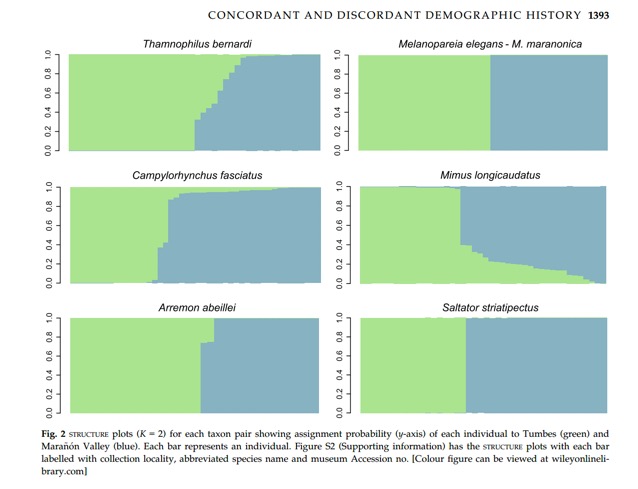

Oswald et al. (2017) included bernardi and shumbae

in their analysis of genetic divergence between Tumbesian and Marañon taxa in

six passerines. Using DNA sequencing and

SNPs, they found evidence for substantial gene flow from nominate bernardi

into Marañon shumbae. Although

this was the only one of their focal taxa known to be in direct contact, the

degree of gene flow was similar to or greater than that detected between

Tumbesian and Marañon subspecies of Mimus longicaudus and Campylorhynchus

fasciatus; in contrast, gene flow detected between one taxon pair (Melanopareia

elegans/M. maranonica) ranked as species was zero The other two subspecies

pairs showed zero (Saltator striatipectus peruvianus/S. m. immaculatus)

or negligible (Arremon a. abeillei/A. a. nigriceps) evidence of gene

flow (and those cases suggest a closer look is needed at their taxonomy.)

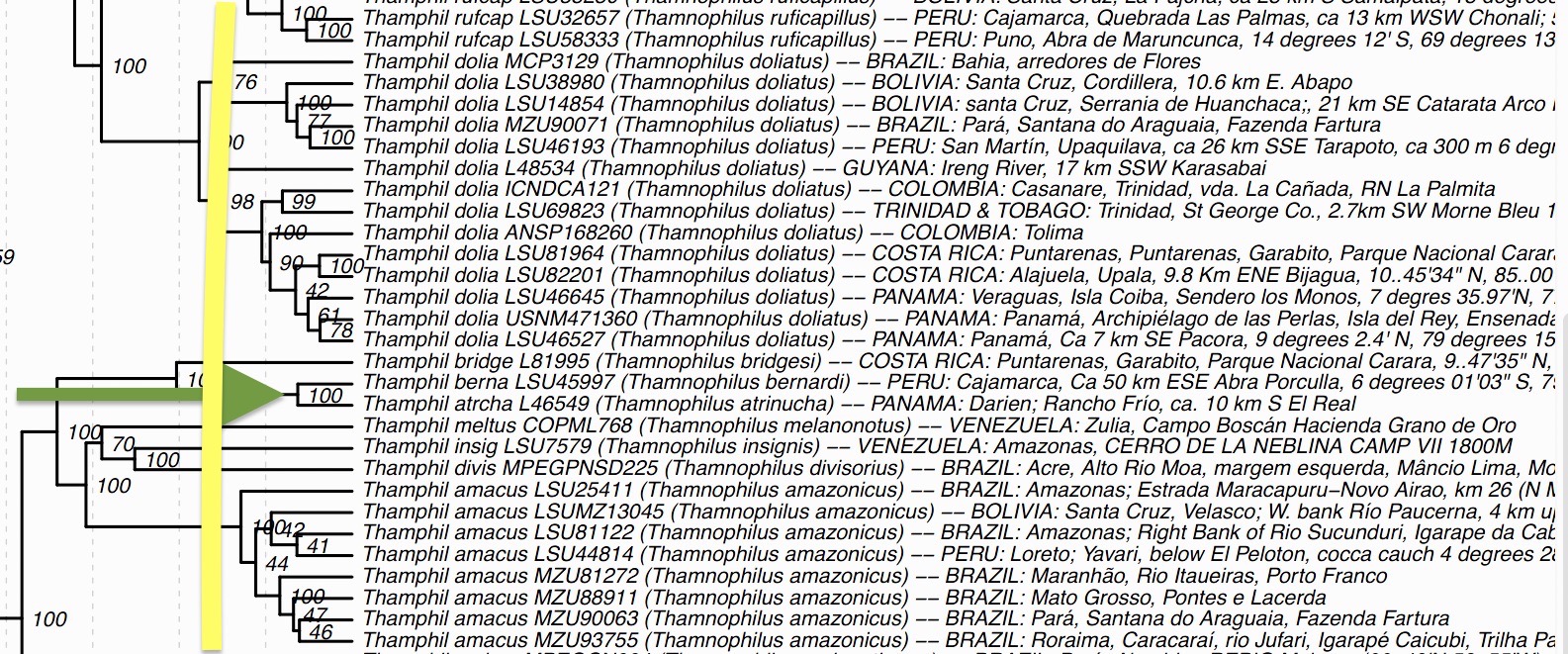

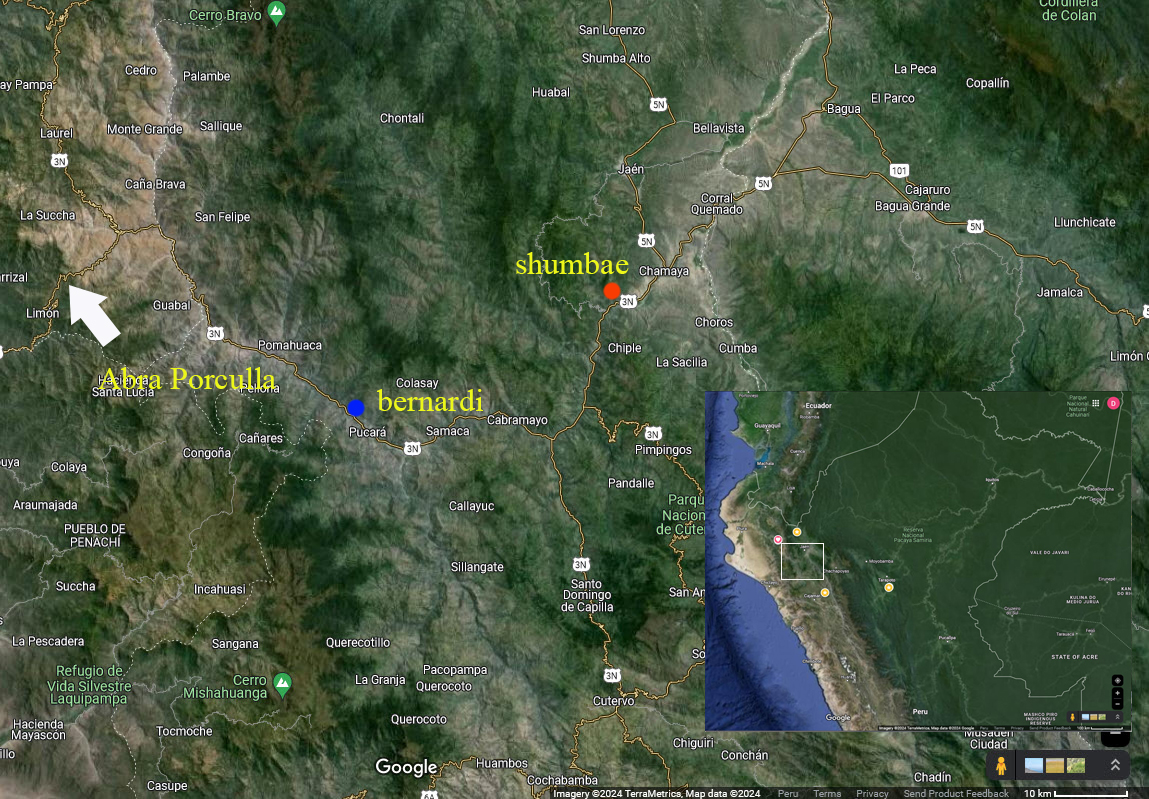

Harvey et al.(2020), with its

comprehensive taxon-sampling, included bernardi but not shumbae. The locality of their sample (ca. 50 km SE

Abra de Porculla; see voucher specimen by Dan Lane in specimen photographs)

places it in that part of the Marañon drainage within the range of bernardi,

in fact close to a putative contact zone.

Here is the relevant portion of the Harvey et al. tree. The green arrow points to Thamnophilus

bernardi and its sister species, a surprisingly closely related T.

atrinucha from Darién. The yellow

vertical line marks the depth in the tree of nodes at the species/subspecies

boundary according to current taxonomy.

Note that the branch lengths uniting bernardi and atrinucha

are actually shorter than those uniting almost any other traditional

subspecies. That’s a shocker. Boldly assuming that shumbae is more

closely related to bernardi than to atrinucha, then that branch

length would be even shorter. Although I

don’t think relative genetic distance data are useful in determining species

vs. subspecies rank, for those that do, note that shumbae would fall at

the extreme short end of branch lengths that unite subspecies.

Discussion

and recommendation:

All we really have to go on, in my opinion, is the difference between the

songs. I’m going to try to get an

antshrike song expert to take my vote on this.

If only there were some playback trials!

Obviously, it would be best if we could get a bird’s ear view of whether

the differences we can hear are sufficient to be a barrier to gene flow.

English

names: Del Hoyo and Collar (2016) used “Maranon

Antshrike” for shumbae and retained “Collared Antshrike” for bernardi. Because their ranges differ so much in size,

and because shumbae is more or less a peripheral isolate, retaining the

parental names is justified for bernardi. Marañon is not a good choice for shumbae

because Collared also occurs into the western Marañon drainage, in at least one

valley: the Río Chamaya (where the LSU sample is from). Also, we have a plethora of Marañon

Somethings. Do we really need yet

another one? I also foresee a problem

with birders naturally calling their first individuals as they enter the

Marañon drainage from the west “Marañon Antshrikes.” With these negatives, I think it’s worth a

separate proposal on English names.

Something like “Freckle-faced” would call attention to a conspicuous plumage

difference between the two and make people actually look at the bird. Dan Lane (pers. comm.) suggested Chinchipe Antshrike

or Pallid Antshrike. Jaen

Antshrike? Shumba Antshrike? Apparently, there is no current place called

Shumba but there is a Shumba Alto, a Shumba Baja, and a Cruz de Shumba all

north of Jaén. A local name might boost

conservation efforts in the region.

Further discussion postponed until if/when the current proposal.

References (see SACC Bibliography

for standard references)

Boesman, P. 2016. Notes

on the vocalizations of the Collared Antshrike (Sakesphorus bernardi). HBW Alive Ornithological Note 54: In Handbook

of the Birds of the World Alive. Lynx

Edicions.

OSWALD, J. A., I.

OVERCAST, W. M. MAUCK III, M. J. ANDERSEN, AND B. T. SMITH. 2017.

Isolation with asymmetric gene flow during the nonsynchronous divergence

of dry forest birds. Molecular Ecology 26: 1386–1400.

Van Remsen, June 2024

_____________________________________________________________________________________________

Vote tracking chart:

https://www.museum.lsu.edu/~Remsen/SACCPropChart968-1043.htm

Comments

from Lane:

“I'd be interested to hear what Kevin has to say, as I had heard that he and

the Islers had investigated the shumbae/bernardi situation nearly

20 years ago and the distinctiveness of the two was disappointingly less

obvious than they had hoped (or so I was led to believe), and so the project

didn't progress further. My gut feeling is: given that both taxon groups are

found on the same side of the Porculla Pass (I have localities for the two that

are about 28 km apart, see map, straight-line-distance, along the Chamaya River

with no obvious biogeographic barriers between them, other than perhaps a

constriction of the valley walls along one stretch), and the distinctive female

plumage and voice, they probably would react to one another as different

species. But that's just a hunch and I've not been able either to document actual overlap or do much

playback experimenting. But if Kevin can elaborate on what he and the Islers

were able to ascertain of the two forms, that would help me decide how to vote

on this split.”

Comments

from Stiles:

“A tentative NO for recognizing T.

shumbae, but if information on different vocalizations can be

substantiated, this would tip the balance to a YES for me.”

Comments

from Jaramillo:

“NO – but a more substantial vocal analysis would be nice to have. It may tip

things the other direction into convincing all a split is the way forward….

Maybe?

Comments

from Jessica Oswald (voting for Remsen): “NO, based on the

evidence presented herein.

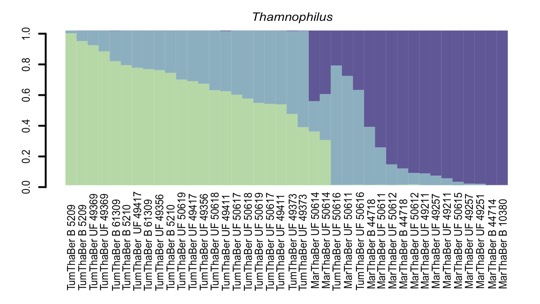

“Oswald et al. (2017) found that the best fitting demographic

model across all focal species was isolation with asymmetric migration from

Tumbes into the Maranon Valley. Estimates of divergence between

Thamnophilus bernardi subspecies

was during the Pleistocene (which could be as recent as ~12,000 years ago).

STRUCTURE recovered K=3 as the best K value (number of clusters/populations

represented in their dataset) for T.

bernardi. “The poorer fit of Thamnophilus [bernardi]

and Campylorhynchus [fasciatus] to a two-population (Tumbes – Maranon Valley)

model may be due to the shallow divergence of these taxon pairs, potentially

gene flow from an unsampled population in Tumbes, or genetic drift (Falush et

al. 2016).” Indeed, the geographic sampling of Oswald et al. (2017) of

T. bernardi

is restricted to a few sites in Peru so additional data from

Ecuador would be potentially informative.

“Further, I’m curious if there are any plumage or song differences

in individuals in Ecuador (coastal individuals or near Loja) as compared to

Peruvian birds.

“Playback data would be fantastic from across this species range.”

Comments from Areta: “I vote NO to the

recognition of T. shumbae. In our

WGAC exercise I have followed Harvey et al. in their interpretation that the

specimen sampled pertained to shumbae (and

this is what their supplementary table indicates), thus it was a surprise to

see that the specimen actually pertains to bernardi.

This does not change the interpretations substantially, as it is clear that a

study comparing shumbae, bernardi and atrinucha is needed. Oswald et al (2017) indicated that their

STRUCTURE analyses found K=3 to be the best. This is not shown in the main

STRUCTURE figure in the paper, but rather in the Figure S3:

“Incidentally,

here is where a map would have been very useful to understand how geography and

genetics map together.

“The vocalizations sound indeed quite different, as

described in Schulenberg et al (2007), and Dan´s recordings of birds only 28km

apart provide a very suggestive piece of evidence. I see merit in the

hypothesis of shumbae

being a different species, but I cannot discard that the current subspecific

status is inadequate. This is the type of case in which a focus study can help

clear any doubts. It makes me uneasy to split taxa without a more clear

understanding of what seems to be, superficially, a good split, and the data on

asymmetric gene flow in Oswald et al. (2017) indicates that the situation is

not as clear-cut as it may seem in principle.”

Comments from Gustavo Bravo (voting for Elisa

Bonaccorso): “NO. As in the case of

S. canadensis (SACC 999), when you look at the

extremes of the range, there seems to be diagnosable phenotypic differences to

potentially elevate population to species status. However, as you move closer

to contact zones, things get messy and clinal variation associated with environmental

variation seems to be the case. What is missing is solid data. In T. shumbae’s

case, we at least have Jess’s genomic data, which seems to support my

interpretation.”

Comments from Zimmer: “YES. Of all of the many unfinished projects that

time conflicts have relegated to my backburner over the years, this one is one

of my bigger regrets. I made the first

audio recordings of shumbae on my first visit to the Marañon Valley back

in 2002 (I think). Finding it and

recording it was actually high on my radar, because Mort Isler and I were hard

at work on the antbird chapter for HBW Volume 8, and shumbae represented

something of a mystery, because there were no audio recordings of it in the

Islers’ extensive antbird vocal archives, and because the subspecies was

described (if I’m remembering correctly) from a female specimen, so we weren’t

even entirely sure about the parameters of male plumage characters. On this initial trip, I was actually scouting

out an itinerary for a fairly comprehensive Northern Peru tour, which had me

spending a lot of time in the Tumbes Region to the northwest, where other

recognized subspecies of S. bernardi were quite common. Accordingly, by the time I reached the

Marañon Valley, I had already seen, videotaped, and tape-recorded a number of bernardi. While searching for shumbae, I

periodically trolled with recordings of nominate bernardi I had just

made in the preceding week, and was frustrated to get zero response. Eventually, I stumbled across a spontaneously

singing/calling male shumbae and recorded it. With the bird in sight, I tried playback of

nominate bernardi songs and male-female duets (both of which I had

broadcast all over the area off-and-on over the preceding couple of hours),

neither of which elicited any detectable response from the male shumbae. After giving it a rest for a couple of

minutes, during which the bird continued to forage quietly, I then played back

the bird’s own spontaneously given vocalizations that I had recorded several

minutes earlier. This elicited an

immediate response, as the male approached me, raising and lowering its crest,

and resuming calling, before starting to sing.

I immediately began taping the song, and before long, a female appeared

and joined the male in singing and calling.

I was blown away by how much faster the song was compared to all of the

nominate bernardi that I had been hearing and recording for days. Over the next few days, and again, when I

returned in 2003, I made efforts to locate and tape record as many shumbae

as possible, and each time I found a new territory, I made a point of

performing similar playback trials, presenting the birds first with playback of

songs, calls and duets of nominate bernardi, followed by a break, and

then presenting them with songs, calls & duets of shumbae. In each instance, there was a complete

absence of response to playback of bernardi vocalizations, followed by a

strong and immediate response to playback of shumbae vocalizations. In the process of my investigations, one of

the things I was curious about, was establishing whether or not there was a

contact zone between bernardi and shumbae, so I worked my way

from the valley floor back upslope toward Abra Porculla, surveying for antshrikes

of either taxon as I went. I ended up

finding several more pairs of each, always assortatively mated, no sign of

intermediate phenotypes (in voice or plumage), and no actual contact zone. I conducted reciprocal playback experiments

with all of the bernardi that I found, presenting them with songs &

duets of shumbae, followed by a break, and then, songs and duets of bernardi. The results were similar – no bernardi

ever responded to songs/duets of shumbae, but did respond strongly to

songs of other bernardi. I did

find territories of bernardi and shumbae that were separated from

one another by as little as 30-35 road km, with no obvious barrier to dispersal

(e.g. large river, steep canyon, major habitat-shift other than gradually

increasing aridity the lower downslope you went toward the Marañon Valley floor). It seemed to me that the two taxa were

essentially parapatrically distributed in this area, and that they were

behaving as would be expected from two distinct species under the BSC.

“Needless to say, I was pretty

pumped about this, and so was Mort Isler when I returned home from the first

trip and told him about it. We

immediately got to work on it, and Mort began a thorough vocal analysis comparing

of all of my shumbae recordings, with what was already a pretty

extensive set of archived bernardi recordings from throughout its range.

“Somewhere during this process (I

can’t remember if it was after my first trip or after my second, the following

year.), Dan Lane returned from a Peru trip, wherein he had independently found

and recorded shumbae for the first time.

Dan also recognized the distinctiveness of shumbae, and contacted

Mort, who told him we were already actively working on it. My recollection is that Dan contributed

additional recordings and data, and, at Mort’s request, made detailed

descriptions of specimens of shumbae from the LSUMNS collection, and it

was our intention to add Dan as a coauthor on the paper.

“For the vocal analysis, Mort

divided the overall sample of S. bernardi (sensu lato) recordings into 5

clusters, 4 of which corresponded to the named subspecies at that time (bernardi,

piurae, cajamarcae, and shumbae) along with a 5th cluster

of recordings that fell midway between the type localities of piurae and

cajamarcae, and which Mort labeled as piurae/cajamarcae for

convenience, with no taxonomic implications.

This provided a basis for examining the possibility of clinality in

vocalizations. Mort analyzed recordings

of 105 individuals from 32 different localities. Although all vocalizations were examined

spectrographically (e.g. for note shape differences), only loudsongs were

measured. Whenever possible, Mort

measured 3 songs per individual. He

obtained 63 measures and ratios reflecting 12 vocal characters, including the

number of notes; duration, pace (notes per second), change in pace, note shape,

change in note shape, note length, change in note length, interval (space)

length, change in interval length, frequencies of note peaks, and change of

note peak frequencies.

“Recording measurements were

analyzed in three steps. First, loudsong

measurements for males and females were compared within each population. Second, data for both sexes were aggregated

by population, and characteristics of loudsongs of the five populations were

compared. Third, data for shumbae

were compared to an aggregate of the remaining populations. Spectrographic examination allowed us to

identify 6 basic types of vocalizations:

loudsongs, softsongs, bark, bark-roll, growl, and caw (caws were highly

variable in length and pitch). Except

for loudsongs, no diagnostic differences could be distinguished between

populations for any of these types of vocalizations, although it should be

noted that the inventory of calls was very small for some populations. The remainder of the analysis, and all

measurements, was confined to loudsongs.

‘The first step, a comparison of

male & female loudsongs within each population, found no diagnostic sexual

differences, although our sample contained no recordings of female loudsongs

for cajamarcae, and only 2 for nominate bernardi. Consequently, male and female recordings were

combined for the remainder of the analysis.

“In the second step, the combined

date for both sexes were compared for the five populations. Diagnostic differences were found between shumbae

and the remaining 4 populations in pace and change of pace (degree of

acceleration), with the acceleration in shumbae songs being most

pronounced in the second half of the song.

There were no diagnostic vocal characters distinguishing any of the

other 4 populations from one another.

“In the final step, data from shumbae

were compared to the combined values for all of the (aggregated) remaining 4

populations. Again, loudsong differences

between shumbae and the aggregated populations were found to differ

diagnostically in both pace and acceleration of pace.”

“Because no vocal characters were

found to distinguish loudsongs of populations described as nominate bernardi,

piurae, and cajamarcae, and because our examination of specimens

revealed that alleged plumage distinctions between the named subspecies were

inconsistent, and showed evidence of clinality, we ended up merging cajamarcae

and piurae with nominate bernardi, in our HBW chapter (2003),

wherein we recognized only two subspecies, bernardi and shumbae. On the other hand, our vocal analysis

revealed that loudsongs of shumbae were distinguished from the remaining

populations by two independent vocal characters. Although fewer in number than typically found

in syntopic pairs of closely related thamnophilid species (Isler et al 1998),

the two independent diagnostic vocal characters, combined with the finding of

parapatry, strongly indicated to us, that shumbae and bernardi

should be considered specifically distinct.

“We then asked Robb Brumfield to analyze tissue samples of bernardi

and shumbae (I don’t remember if this was a bird that Dan collected – he

could probably fill that part in.), to see if molecular distance coincided with

the vocal differences. In piecing

together old email threads, I see one from Robb to Mort, dated 6/24/2004 that

said “The two Sakesphorus bernardi bernardi and S. b.

shumbae are divergent by only 0.6%.

That’s pretty minimal for species.”

That was followed 2 days later, by an email from Mort to me, in which

Mort relayed to me the following: “I

talked to Robb after I spoke with you yesterday. He is quite open to the possibility that

molecular distances found under current procedures might not correspond to

species level differences under the BSC, and he agrees that the paper should go

ahead.”

“I remember that we were a little

discouraged that the molecular data were not strongly supportive of our

taxonomic conclusions, but also thinking that perhaps the divergence was just

really recent in evolutionary terms, and the fact that the two forms seemed to

be existing in parapatry, with no phenotypic signs of intermediacy in plumage

or vocalizations, meant that they were behaving as distinct biological

species. And, while it was true that the

vocal analysis only revealed 2 independent, diagnostic vocal characters (as

opposed to the 3-character yardstick of Isler et al, 1998), the ranges of those

two characters were not only non-overlapping between shumbae and bernardi,

but mean values were not even close statistically.

“Somehow, although it was our

intent to proceed with the paper and make the case for separate species status

for shumbae, we lost momentum.

Mort was concurrently involved in a big paper that was nearing

completion, and I got consumed with work related stuff. I think I was also hoping to make another

trip back to northern Peru to try to further investigate the contact zone

before we submitted the paper, and when that trip didn’t come off, we

completely lost all momentum, and we were both absorbed in a series of other

projects that always seemed to take precedence.

Now, so many of the details seem like ancient history, and it would take

some effort to recreate everything.

“It should be kept in mind that

although we did not identify any diagnostic differences in calls between shumbae

and the other four populations of bernardi, that sample sizes of calls

were limited, and inspection of calls was limited to visual inspection of

spectrograms, without any measurements being made. There are also other groups of closely

related thamnophilid antbirds which are known to differ in their loudsongs, but

which do not differ appreciably in their calls.

Although we identified only two diagnosable vocal characters, the extent

of the differences in those two characters were striking, and the potential

significance of them as isolating mechanisms is reinforced by my series of

reciprocal playback trials. Also, I

think it bears pointing out that our vocal analysis did not find any diagnostic

differences in vocal characters over the much broader range of bernardi,

and then, over the space of < 30 km, with no intervening geographic barrier,

bernardi is replaced by a taxon that differs in morphometrics, plumage,

and at least 2 vocal characters.

Regardless of what the genetics are suggesting, to me, that’s a pretty

strong case for treating these two taxa as separate species.”

Comments from Remsen: “I now recommend

a YES because Kevin’s comments above actually fill in the blanks perfectly in

the information gaps I identified in the proposal. I am especially impressed by the first-hand

account of the playback trials, and I am highly influenced by the documented

abrupt turnover from bernardi to shumbae. Parapatry without evidence of gene flow is

THE strongest evidence one can get for species rank in non-sympatric taxa. As for genetic distances … well, as you can

anticipate, I don’t put much stock in them – they measure time-since-separation

divergence at neutral loci, which is correlated broadly with speciation, but

the correlation is so weak that I never think it should be used as primary

evidence except at its extremes. If one

could measure just the “genetic distance” between the gene complexes that

control song in this case, I suspect that the degree of divergence at those

loci would be substantial, comparatively speaking. These taxa may not have been separated for

very long but obviously long enough for songs to diverge to the point of not

recognizing each other as conspecifics.

“The only reason I can see now, in

my opinion, for rejecting the proposal is that the critical information is not

published in a journal. I can see that

side of the argument, also.”

Additional comments from Bravo: “I read Kevin’s vote –

some bits of which I already knew – and I think it is very telling. However, I

stick to my NO vote.

“It is still necessary to see all those data in published form and

explicitly test for clinal variation. I spent the Summer of 2017 following shumbae

around in the core of its range and the Summer of 2019 following bernardi

in Tumbes. As I said, those two extremes are decisively different vocally

(loudsongs), morphometrically, and in plumage. Still, I would like to see how

those traits vary across the entire range of the species, particularly given

the low genetic divergence and the strong signal of admixed individuals

presented by Oswald et al. (2017). What I think is missing from Kevin’s

described vocal analyses is an explicit test of gradual variation across space.”

Comments

from Lane:

“YES. Wow, well Kevin really delivered there! I should add my own addendum to

his tale. He and I overlapped at the start of a tour he ran in 2002, in which

Kevin kindly allowed me to join him and his group on a day trip to Lomas de

Lachay. During that day out, he told me about his discovery of the different

voices of the two T. bernardi, and that he had found coastal type birds

east of Abra Porculla, which was what inspired me to try to collect some when I

returned to the area in 2003, and I successfully got one female (which,

apparently, is the one that was used in the Harvey et al tree, but was

erroneously identified as shumbae). I had collected a series of T. b.

shumbae in Sept 2002, with recordings, and those tissues should be

available at LSU.

“Anyway,

given the work Kevin has done in playback experiments, the fact that we both

were able to document the two taxa along the same river valley within ~35 road

km of one another without evidence of interbreeding, and the fact that the

coastal (nominate) group of T. bernardi shows no clinal or other shift

in song characters over a huge region, I think the evidence is strong, if

unpublished, in support of species status for T. shumbae. YES.”

Additional

comments from Areta:

“NO. The genetic data is suggesting that something

complex can be happening here, and like Gustavo, I would like to see a proper

paper analyzing this. If there is a mismatch between genomics and phenotype,

then it also should be explained. I am impressed by the amount of work that

Kevin has done, and taking a formal look at the vocal and plumage data in

association to genetics should clarify what´s happening here. Sometime ago I

tried to lure Peruvian students into this complex, but apparently failed to

create enough enthusiasm. This proposal is now making the case very appealing

for further study.”

Additional comments from Robbins: “Reading all those great

comments/data by Kevin leaves little doubt that shumbae should be

considered a species. So, I change my vote to YES.”

Comments from Claramunt: “NO. Kevin’s observations are

very suggestive of reproductive isolation, but the genetic data suggest free

gene flow between the two taxa. Evidently there is a lot of geographic

variation in bernardi

(plumage and voice) that needs to be analyzed and in general, we

need more published information to make an informed decision.”

Additional

comments from Stiles:

“YES. Although the data are clearly not

all there yet, I think that the detailed field experience of Kevin,

especially including the playback experiments, may have tipped the balance

toward considering shumbae a distinct species – so, a tentative YES

here.”

Comments from Rafael Lima: “I was recently reviewing the results of

Oswald et al. (2016) and Boesman (2016) for a paper on antbird speciation, and

I wanted to share some thoughts in the interest of understanding the rationale

behind the votes in favor of splitting Thamnophilus bernardi.

“The song differences between bernardi and shumbae are

indeed impressive, greater than those between several closely related syntopic

antbird species. Most importantly, the fact that they strongly discriminate

each other's songs suggests that these differences could generate strong

premating isolation. However, the genetic evidence suggests substantial gene

flow between them.

“This case initially reminded me of the situation with Hypocnemis

and Willisornis, where vocally distinct antbirds hybridize despite

marked vocal differences (Pulido-Santacruz et al. 2018, Proc. B. 285: 20172081;

Cronemberger et al. 2020, Evolution 74: 2512-2525). I wondered whether

postzygotic isolation might be at play, as seen in those genera. But this seems

not to be the case with bernardi and shumbae. For instance,

consider samples FLMNH 50616 and LSUMZ B-44718 in Fig. S2 of Oswald et al.

(2016). Both exhibit noticeably admixed genotypes. According to Supporting

Information Table S1 of Oswald et al. (2016), sample FLMNH 50616 is from

"Coto de Caza El Angolo, Los Pilares, 4.5 km SE Fernandez (-4.22,

-80.84)" and sample LSUMZ B-44718 is from "Las Juntas, junction of

rios Tabacomas and Chinchipe (-5.62, -78.53)." These two locations are 300

km apart. It therefore appears that genetic admixture is taking place over 300

km between bernardi and shumbae.

At k = 3, admixture seems even more extensive (see Fig. S3). Unlike Hypocnemis

and Willisornis species, which form very narrow and strongly bimodal

hybrid zones, bernardi and shumbae appear to form a wide zone of

genetic intergradation.

“One possible interpretation is that assortative mating between bernardi

and shumbae may be strong but incomplete. Recent theoretical work

indicates that assortative mating effectively maintains species boundaries only

when it results in essentially complete premating isolation (Irwin 2020, Am.

Nat. 195: 150-167). If assortative mating is strong but incomplete, it may not

generate strong overall reproductive isolation unless accompanied by postmating

isolating barriers. It is plausible that bernardi and shumbae

exhibit strong but incomplete assortative mating based on vocalizations and

weak or nonexistent postmating barriers, resulting in weak overall reproductive

isolation.

“My interpretation is that bernardi and shumbae are

experiencing extensive gene flow *despite* marked vocal differences and strong

behavioral song discrimination. Since overall reproductive isolation is what

determines species limits, the currently available evidence suggests a single

species. I am curious to understand the rationales behind the "YES"

votes, given the evidence of extensive gene flow.”

Response from Remsen: My

response to Rafael is that not all gene flow is alike. The evidence for extensive gene flow in this

case comes from SNP data, i.e., differences in which a single nucleotide in a

DNA sequence is replaced by another.

Whether these have any relevance to the bird’s biology and whether these

are influenced directly by natural section is not known. As known for a long time (e.g. in Brumfield Manacus

papers), presumably neutral genetic differences (e.g. mtDNA sequence

differences) are much more labile in terms of gene flow, whereas phenotypic

characters likely under strong selection, e.g. things important to reproductive

isolation such as song and plumage, do not necessarily show the same pattern

and may show abrupt shifts from one taxon to the other. My interpretation of both the vocal and

plumage data in this system is that there is an abrupt shift, which suggests

assortative mating at contact, albeit incomplete.”

Comments from Bonaccorso: “My vote

on this one was given to Gustavo and I agree with him that without a formal

clinal analysis, Kevin’s ideas remain hypotheses that need to be tested.

Therefore, I support his NO vote.”

Comments from Jaramillo: “YES. I

am a big fan of playback experiments to ask the birds what they think. Even a

small number of experiments on suboscines can do the trick. The most

informative result is that the vocalization is ignored, while same taxon

vocalizations are not ignored. Yes, it would be great to have this published,

but enough is out there and with these additional comments I am more

comfortable with a YES vote at this point.”