Proposal (1038) to South American Classification Committee

Merge Milvago

and Phalcoboenus into Daptrius

Note: This proposal’s origin started with a query from Joel Cabezas Salazar

about why SACC maintained Milvago and Phalcoboenus when

Clements/eBird has merged them into Daptrius. I was aware of the Fuchs et al. papers (see

our SACC Note below) but was not aware that Clements/eBird had already

instituted this merger without the issue first being considered by SACC and

NACC. Now I have also learned that WGAC

also went ahead and merged these genera way back in 2022, and this was followed

by Clements/eBird. I now have access to

the WGAC deliberations, which have influenced some of the discussion below.

Effect on

SACC: This would

merge two long-recognized genera, Milvago Spix 1824 and Phalcoboenus

d’Orbigny 1834, into Daptrius Vieillot 1816.

Background: Generic boundaries in the

caracaras have always been fluid, with virtually every combination or mergers

among Caracara (formerly Polyborus), Ibycter, Daptrius,

Milvago, and Phalcoboenus.

For example, see our SACC notes 2 and 3b as well as 7b, copied below, as

well as the synonymies in Hellmayr and Conover (1949). However, to the best of my knowledge, Milvago

and Phalcoboenus have been maintained since at least Peters (1931) and Hellmayr

and Conover (1949) until the Clements merger.

Here are our

current SACC Notes:

7b.Vuilleumier

(1970) proposed that Milvago be merged into Polyborus (= Caracara),

but genetic data (e.g., Griffiths et al. 2004) indicate that they are not

particularly closely related. Fuchs et

al. (2012) found that Milvago itself

is not monophyletic, with chimachima

sister to Daptrius and chimango sister to Phalcoboenus; they recommended transfer of chimango to Phalcoboenus. This was followed Del Hoyo & Collar

(2014). SACC proposal did not pass to transfer Milvago chimango to Phalcoboenus.

Dickinson & Remsen (2013) transferred Milvago and Phalcoboenus to Daptrius. Fuchs et al. (2015) merged Milvago, Ibycter, and Phalcoboenus

into Daptrius without providing rationale.

SACC proposal badly needed.

7c. Amadon

& Brown (1968) proposed that the two species of Milvago be

considered superspecies; Vuilleumier (1970), however, pointed out that their

degree of sympatry negated this treatment; although he considered them closely

related, he also pointed out that they differed in morphology and likely also

in ecology. Fuchs et al. (2012) found

that they are not sister species – see Note 7b.

SACC proposal

561 dealt with

this issue in 2012. That proposal was to

move chimango to Phalcoboenus based on Fuchs (2012) was

unanimously defeated; see the comments therein, especially by Mark Pearman and

Sergio Seipke, concerning various phenotypic similarities and differences among

the species. The theme of the comments

suggested that a new genus for chimango was the best way to express

phylogenetic and phenotypic, but there being no such genus, SACC left Milvago

as a paraphyletic taxon. As one can see

from the comments, there was fair support for merging all into Daptrius

as a solution, but visceral opposition to also including Ibycter, as

done subsequently by Fuchs et al. (2015), but no further action was taken.

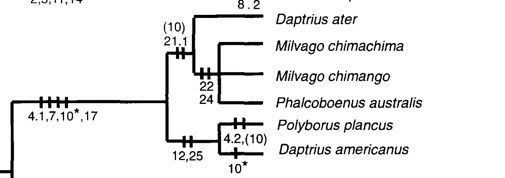

Previously, Griffiths’

(1994) analysis of syringeal morphology was consistent with Daptrius

(minus Ibycter americanus), Milvago, and Phalcoboenus

forming a clade:

Griffiths

(1999) then combined syringeal data with about 1000 bp of cytochrome b genetic

data to produce similar results, although M. chimango was missing from

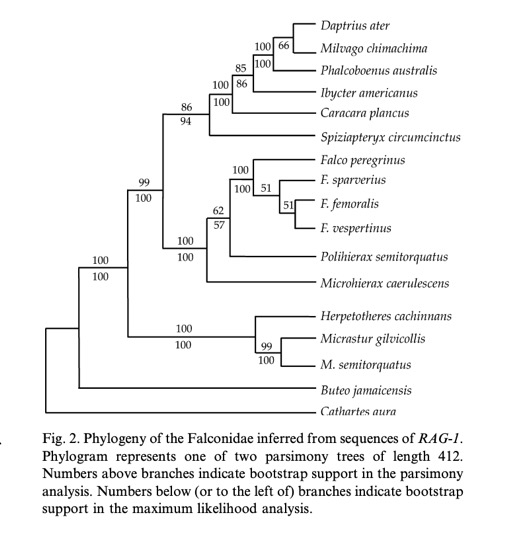

the genetic analysis. Griffiths et al.

(2004) analysis of RAG-1 sequences produced a different but weakly supported

typology but still found the three genera to form a strongly supported clade

(but M. chimango still missing):

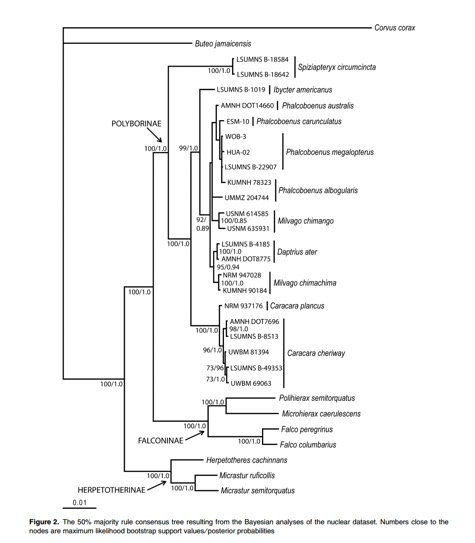

Fuchs et al.

(2012) were the first to include M. chimango (thanks to two USNM

samples), and both mtDNA and nDNA gene trees showed that chimango was

sister to D. ater with reasonably strong support, e.g.:

I don’t see

any reason to dispute their findings; they even have more than 1 individual of

the critical taxa.

Discussion:

Concerning

the surprise that Milvago is not monophyletic, I suspect that part of

the reason for their traditional treatment as congeners is that base color of

the juvenal plumage of chimachima is dark brown, much like the plumage

of adult chimachima, to the point that confusion in the field is evidently

possible. Somehow, I had it my head,

perhaps from over-interpretation of what I had read, that this might even be a

case of neotenic plumage retention. However,

I now consider that unlikely: the plumage patterns of the two superficially

similar plumages differ in many ways, as can be seen in the photographs from

Macaulay below, and as mentioned in our Bolivia guide (Herzog et al. 2016):

Look

at the differences in ventral and dorsal patterning, as well as differences in

the facial area, especially with respect to how much the eye stands out. Below are severely cropped head shots of

adults from photos in Macaulay: chimachima on left (from Risaralda by David

Monroy Rengifo), chimango on right (from Santa Fe by Horacio Luna); one

can interpret the similarities as subjective evidence for placement in same

genus, or the differences as subjective evidence for placement in different

genera). By the way, the iris color

difference holds up in all the photos I examined:

So,

in my opinion, the finding that chimango and chimachima are not

sisters is not that surprising. One

could also make an ex-post-facto case that a chimango + Phalcoboenus

relationship makes more sense biogeographically (temperate zone), as does a chimachima

+ Daptrius ater relationship (tropical rivers); we (Herzog et al.

2016 Bolivia guide) noted that the latter’s primary calls are fairly similar.

Therefore,

I see no better option for now than transferring chimachima to Daptrius. Note also the relative short branch lengths

in the tree (subsequently used by Fuchs et al. 2015 to merge all taxa into Daptrius. So, Milvago chimachima would become Daptrius

chimachima). This would retain Milvago

chimango in a monotypic genus, solving the problem of non-monophyly of Milvago

as well as not messing with traditional Phalcoboenus. However, the type species of Milvago

is chimachima, and therefore unavailable for chimango, and

therefore chimango must be transferred to Phalcoboenus or have a

new genus named for it. In the absence

of the latter, we have no choice but to include chimango in Phalcoboenus

or merge all into Daptrius.

Fuchs et al.

(2015) used the data in Fuchs et al. (2012) to merge Milvago and Phalcoboenus

as well as Ibycter into Daptrius.

WGAC retained distinctive Ibycter but did merge the other two

into Daptrius. Certainly from the

tree in Fuchs et al. (2012), one can see the rationale for merging Milvago

and Phalcoboenus into Daptrius: note the short branch lengths and

the slightly suboptimal support for the node that divides them into two groups.

I can see

reasons for not wanting to further expand Daptrius. Note the phenotypic and ecological

differences noted between Phalcoboenus and the rest as expressed

qualitatively in SACC 561, in which a merger was rejected.

As I see it

there are only three alternatives:

(1) Maintain

status quo by retaining Milvago as a non-monophyletic taxon and hope

that someday someone will describe a new genus for chimachima. This would mean a NO vote on the

proposal. I personally view this as

unsatisfactory for obvious reasons.

(2) Transfer chimachima

to Daptrius and chimango to Phalcoboenus. This would retain Phalcoboenus but

“contaminate” that group by inclusion of chimachima. This would also mean a NO vote on the

proposal, and result in a new proposal, 1039x.

(3). Transfer

Milvago and Phalcoboenus to Daptrius. This will generate a negative reaction from

many who know these birds (but so would option 2). I regard it as the least unpalatable of the

options. It acknowledges that many

genera, including raptors, include distinctive groups within them, including for

example Falco. Therefore, I

somewhat reluctantly recommend a YES on #3.

Lit Cit (see SACC Bibliography for the rest):

FUCHS, J., J. A. JOHNSON, AND D. P. MINDELL. 2012.

Molecular systematics of the caracaras and allies (Falconidae:

Polyborinae) inferred from mitochondrial and nuclear sequence data. Ibis 154: 520–532.

FUCHS, J., J.

A. JOHNSON, AND D. P. MINDELL.

2015. Rapid diversification of

falcons (Aves: Falconidae) due to expansion of open habitats in the Late

Miocene. Molecular Phylogenetics and

Evolution 82: 166–182.

GRIFFITHS, C. S. 1994. Monophyly of the Falconiformes based on syringeal

morphology. Auk 111: 787–805.

GRIFFITHS, C. S. 1999. Phylogeny of the Falconidae inferred from

molecular and morphological data. Auk 116: 116–130.

GRIFFITHS, C. S., G. F. BARROWCLOUGH, J. G. GROTH, AND L. MERTZ. 2004.

Phylogeny of the Falconidae (Aves): a comparison of the efficacy of

morphological, mitochondrial, and nuclear data. Molecular Phylogenetics and

Evolution 32: 101–109.

Van Remsen, December

2024

___________________________________________________________________________________________________

Vote tracking chart: https://www.museum.lsu.edu/~Remsen/SACCPropChart968-1043.htm

Comments

from Robbins:

“YES (option 3). I understand why some

might not want to merge Milvago and Phalcoboenus into Daptrius,

but I think the proposal’s explanation of why this is the best option is sound.

Thus, I vote for option 3.”

Comments

from Lane:

“NO. I vote for 2. I really dislike the idea of collapsing everything into Daptrius,

as I just don’t see the whole group fitting well into a single genus. I would

prefer putting chimachima into Daptrius (both are “warm-country,”

lowland river-edge spp) and chimango into Phalcoboenus (all are

“cold country” spp, and chimachima is basically a neotenic Phalcoboenus

in plumage). I know chimachima only from a few observations, so I don’t

have a strong a feel for the beast in life but given that it is the most

northerly lowlander in the “Phalcoboenus clade,” I can accept its

smaller, more delicate structure as still representing that group as per

Bergmann's Rule.”

Comments

from Zimmer:

“NO. To borrow Van’s phrasing, I am going to have to

vote for the “least unpalatable of the options”, which, for me, is Option 2,

following Dan’s reasoning, and, with the hope that someone will come along and

erect a monotypic genus for chimango, so that we can then restore the

cohesiveness of Phalcoboenus.”

Comments from Areta: “NO. Here we are again on

this... If we only had already described that new genus for chimango, I would go for it. I often

regret that the explosion of phylogenetic information has not been accompanied

by equally detailed phenotypic studies (of course: it takes more time to

understand the birds than to produce phylogenetic trees) and taxonomic works

(of course: high-impact journals mostly do not care about this). This is one of

such cases. This, in the context of a global movement to have fewer genera at

the expense of smaller neat groupings, has resulted in an all-encompassing Daptrius that is not very useful for

communication. The fact that all species in the clade at stake are recently

diverged adds another layer of complexity. I would love to have one genus for americanus (Ibycter), one for ater (Daptrius),

one for chimachima (Milvago), one for chimango

(undescribed), and one for the Andean-Patagonian caracaras (Phalcoboenus). This 5-genera treatment

is not in the proposal, and, given the recent generic-lumping move, I doubt

that it will gain much traction, unless thoroughly justified.

“I

do not like it when the pressure to change generic limits because of new

phylogenetic information leads to rapid assessments. Sometimes the

taxonomic-nomenclatural matters need time to be sorted, and creating ephemeral

new combinations strictly on phylogenetic data should not be recommended. But

we are here, in this century in which waiting does not seem like an option.

Meanwhile, the literature will be filled with Daptriuses until someone contests

the broad Daptrius. Thus, given all

this, and also voting for the least unpalatable of the currently available

options in the proposals, I vote for option B: Daptrius ater and Daptrius

chimachima, and Phalcoboenus chimango

+ the four traditional Phalcoboenus

(and of course, retaining Ibycter

americanus). Meanwhile, I´ll try to get to describe a new genus for our

beloved chimango or tiuque.”

Comments

from Niels Krabbe (voting for Del-Rio): “NO. After reading the earlier comments, I

vote yes for option 2 (transfer chimachima to Daptrius and chimango

to Phalcoboenus) and await Nacho's description of a new genus for chimango

and a following new proposal.”

Comments

from Fabio Raposo (voting for Bonaccorso): “NO. I vote for option 2, and I agree

with Dan Lane's points regarding ecological segregation. It is important to

note the short length of some branches, and genomic-era datasets may help us

understand the stability and strength of the relationship between M.

chimango and the Phalcoboenus clade.”

Comments

from Stiles:

“Option 2 (‘least unpalatable’): preserves the integrity of Phalcoboenus

and is most easily changed when a new generic name for chimango is

finally proposed.”

Comments

from Claramunt:

“NO. I would support instead the dismantling of Milvago by transferring chimachima

to Daptrius and chimango to Phalcoboenus.”