Proposal (1047) to South American Classification Committee

Revise Turdus assimilis/T.

albicollis complex as consisting of four species: (A) treat daguae

as a separate species from T. assimilis, and (B) treat the phaeopygus

group as a separate species from T. albicollis

Note

from Remsen:

This

proposal was written for NACC to treat the T. assimilis-T. albicollis

complex as more than two species, with an emphasis on daguae because it

occurs in the NACC area. Note that we

dealt with this issue in 2021 – see SACC proposal 922. Oscar, Jacob, and I have modified this

slightly to include the option of also recognizing Turdus phaeopygus

as separate from our T. albicollis, despite this not being the main

thrust of the NACC proposal, in case we consider the information herein as

sufficient to treat the phaeopygus group as a separate species. If rejected, we could potentially reconsider

that in a separate, more detailed proposal that focuses strictly on phaeopygus. Currently, SACC treats daguae as a

subspecies of otherwise Middle American T. assimilis and phaeopygus

as a subspecies of South American T. albicollis.

Effect

on SACC:

Splitting T. daguae and T. phaeopygus from T. assimilis

would result in two additional species for the SACC area.

Description of the

problem:

The

assimilis/albicollis complex is found

throughout much of Middle and South America and comprises four main subspecies

groups. The assimilis group is found

in the highlands from northern Mexico in all mountainous regions south to

central Panama. The taxon daguae is

currently considered a subspecies of assimilis

and is found in the lower foothills of the Chocó biogeographic region, from

southwestern Ecuador north to eastern Darién. In the Amazon Basin and the

Guiana Shield, three subspecies represent the phaeopygus group of T.

albicollis. These reach as far north/west as the Sierra de Santa Marta and

as far south as northern Bolivia, Mato Grosso, and Pará. The nominate albicollis group is found in

southeastern Brazil, Argentina, and Uruguay, with an isolated population

(subspecies contemptus) in the Andes

of Bolivia, in close proximity to lowland phaeopygus.

Taxonomic history

The

taxonomic history was covered thoroughly in NACC proposal 2022-A-4 / SACC

proposal 922. Briefly, daguae was

described as a species in 1897 by Berlepsch, but of course in a different era

and different species concept. Peters (1964) considered all four groups to be

members of one species, T. albicollis.

Most authorities have considered daguae

as a subspecies of T. assimilis (of

Middle America) based on plumage similarity. A few recent authorities (e.g.,

HBW BirdLife) have considered daguae

as a subspecies of T. albicollis (of

South America) based on vocal similarity or more recently as a separate species

(Ridgely & Greenfield 2001).

In

early 2021, the Working Group Avian Checklists (WGAC) addressed the placement

of daguae and voted 6-0 to consider daguae as a species separate from both T. assimilis and T. albicollis. However, two WGAC committee members noted that they

wanted to hear from NACC and SACC and would reconsider their votes if those

committees disagreed with that conclusion. Later in 2021, Van Remsen submitted

a proposal to split daguae

concurrently to both NACC (proposal #2022-A-4) and SACC (proposal #922). Those

proposals both failed (respective votes: 4-7 and 4-4), with both committees

retaining daguae as a subspecies of T. assimilis. WGAC has not reconsidered

its vote since these NACC and SACC proposals.

The

SACC proposal is here: https://www.museum.lsu.edu/~Remsen/SACCprop922.htm

And

the NACC proposal (and comments) are here: https://americanornithology.org/about/committees/nacc/current-prior-proposals/2022-proposals/

The

WGAC proposal was based on the same information as what was contained in the

NACC and SACC proposals. We encourage the committee members to read the

NACC/SACC proposal, and especially the comments by committee members on both

proposals.

New information:

No

new information since 2021. We are here again addressing this issue in advance

of the publication of the WGAC checklist, to attempt to minimize discrepancies

between NACC and WGAC. Committee members in both NACC and SACC who voted

against changes to taxonomy raised two main issues: 1) genetic sampling was

insufficient, both spatially and in number of loci, and 2) no formal analysis

of vocalizations was conducted. Although both issues could use additional

research, we present additional clarification on both, that together clarify

some of the issues raised by committee members.

Regarding

genetic sampling, most data come from the mitochondrial tree presented by

Núñez-Zapata et al. (2016) and was included in NACC 2022-A-4 / SACC 922. That

tree showed a sister relationship but with a deep divergence between daguae and assimilis. All the samples of daguae

came from southern Ecuador, far from any potential contact zone, but note that

based on distribution we do not believe that these taxa come into contact. SACC

committee members also noted that there may be multiple species within T. albicollis, and that Núñez-Zapata et

al. (2016) sampled only the nominate subspecies group of southeastern Brazil,

Argentina, Uruguay, and Andean Bolivia. We checked this to be certain, as both

subspecies groups occur in Bolivia, and based on the sampling localities in

Núñez-Zapata et al. (2016), confirmed that both Bolivian samples were from

Andean localities, so represent contemptus

of the albicollis group. We can

confirm, therefore, that the Amazonian phaeopygus

group was not sampled here.

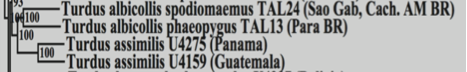

Another

paper (Batista et al. 2020) sampled ultraconserved elements (UCEs) across the

diversity of Turdus, including

multiple taxa in the assimilis/albicollis complex, but the previous

proposals noted that it, unfortunately, did not sample daguae. Batista et al. (2020) did sample UCEs from T. albicollis; however, both subspecies

included (phaeopygus and spodiolaemus) are part of the same

Amazonian subspecies group. UCE data indicated that T. albicollis and T.

assimilis are sister taxa but with a deep divergence. That UCE tree, from

their supplemental data, is shown below.

A

portion of supplemental Figure 2 from Batista et al. 2020, showing UCE-based

phylogenetic relationships in the albicollis/assimilis complex. The node separating albicollis from assimilis was estimated to be 3.16 Mya.

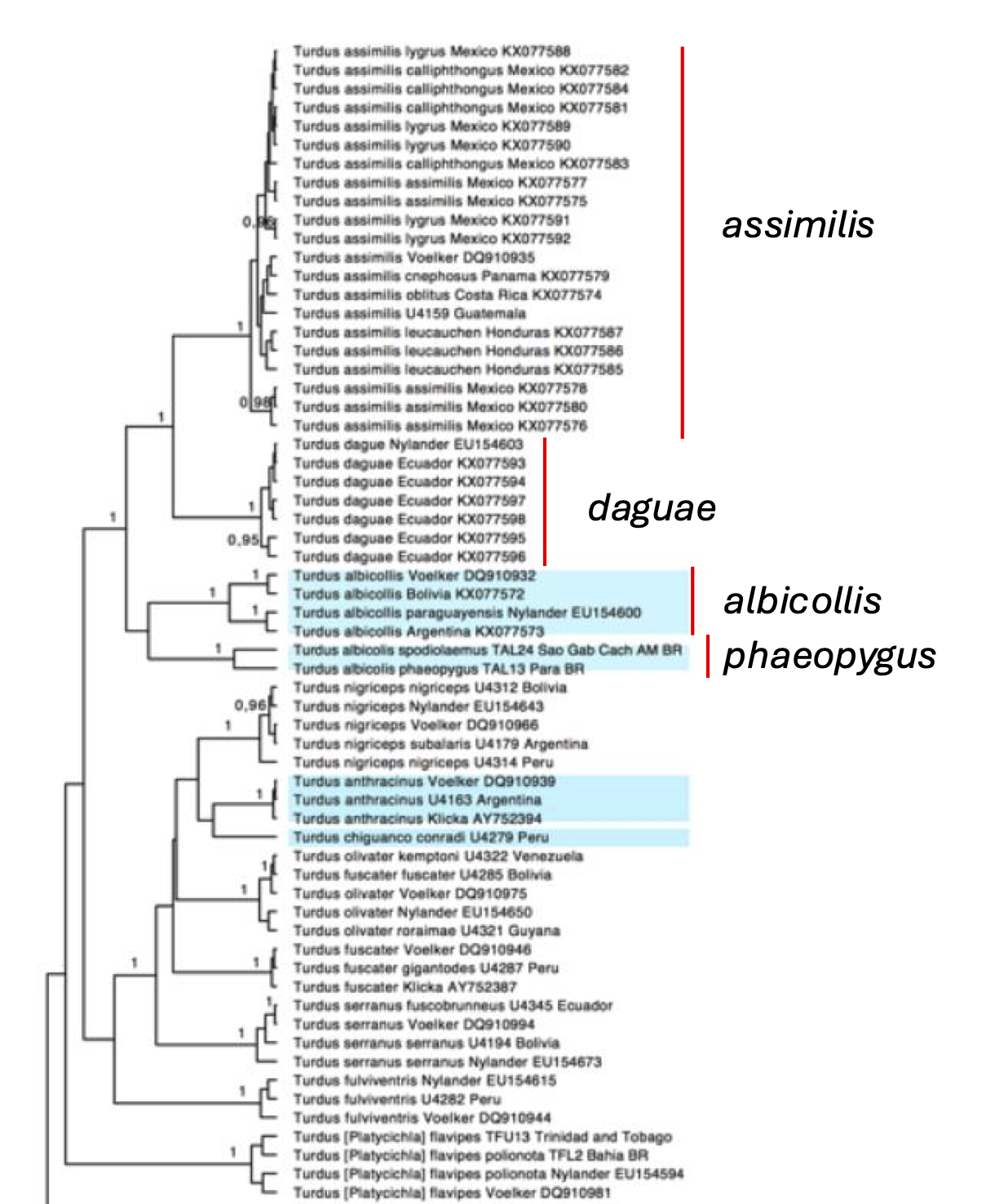

However,

the supplemental data from Batista et al. (2020) show that they did in fact

extract mitochondrial data from their UCE reads, and combined these with

existing mitochondrial DNA samples to estimate a phylogeny that does include

all four major clades in the complex. Although the standard mitochondrial gene

tree issues apply, they do point to deep divergences between all four groups

and resolve the taxon sampling issues raised previously.

A

portion of Figure S5 from Batista et al. (2020) showing the phylogenetic

relationships in the Turdus assimilis/albicollis complex based on the mitochondrial gene cytb. We have highlighted the subspecies

groups of interest here with red bars. The scale bar on this mtDNA phylogeny

figure is difficult to interpret, as the scale bars below 5 Mya are missing,

but by our estimate, the node separating albicollis

from assimilis is approximately 4 Mya

(so, just older than from the UCE data) and the node separating daguae and assimilis is approximately 2.5 Mya. Of note, the node separating phaeopygus/spodiolaemus and nominate albicollis

is approximately 3.5 Mya. The samples highlighted in blue are those determined

by the authors to represent particularly deep intra-specific splits. Note that

the node ages of the four major clades in the assimilis/albicollis

complex are comparable to or older

than other well-established species in the genus.

Phenotypic variation

In

addition to the plumage differences noted in earlier proposals, Vallely and

Dyer (2018) mentioned that daguae

also show a dusky bill tip lacking in assimilis,

which they illustrated as having a solid yellow bill. However, online photos

show considerable variation in dusky coloration on the bill in assimilis, which may be age- or

sex-related. However, the few available photos of daguae show a considerably darker bill, solidly dark in almost all

cases. Herzog et al. (2016) illustrated phaeopygus

as having a solidly dark bill, versus a yellow bill with a dark tip in contemptus of the albicollis group. Photos online show phaeopygus having either a dark bill or a yellow mandible

contrasting with a dark maxilla.

Vallely

and Dyer (2018) illustrated both gray and brown birds for T. assimilis and noted that these populations are known from

adjacent localities in Honduras. Collar et al. (2024) illustrated the

subspecies T. assimilis atrotinctus

of the Caribbean slope of Honduras and Nicaragua as being dark gray and mention

in the text that the subspecies leucauchen

is also dark gray. In our search of online photos and field guide references,

it appears that the brown populations are found in most of Mexico and extend south

on the Pacific slope to southern Guatemala. These are nominate assimilis and some related subspecies,

which are paler and more uniformly brown than other subspecies. Dark gray birds

are found on the Caribbean slope from the humid slope of southeastern Mexico,

south through Guatemala, Honduras, and Nicaragua, and again in the mountains of

most of Costa Rica except the far south (nicely illustrated in Howell &

Webb 1995). In the southern Pacific slope of Costa Rica and through its range

in Panama, there is another brown subspecies, cnephosus, but this one is more contrasting and paler below than

the northern nominate brown subspecies. Most of the above phenotypic

differences were also noted by Hellmayr (1934), but we note that from the

mtDNA, these are all genetically very similar.

Lastly,

a “small and dark” subspecies coibensis

is known from Isla Coiba, but its genetic affinities are unknown. In his

description of coibensis, Eisenmann

(1950) gave the diagnosis as “closest to daguae”,

especially in the underpart and bill color, and that it is different than cnephosus in that regard. Wetmore (1957)

did say that coibensis differs from daguae in being “larger, more olive

above and grayer below, with the unmarked white area on the foreneck less in

extent”, so some plumage differences exist. Wetmore (1957) also provided

morphometrics for coibensis, which

could be compared with other taxa. Eisenmann (1950) used this plumage

similarity as evidence that daguae

was conspecific with assimilis, with coibensis as the geographic

intermediate. However, he also combined all these taxa under an expanded albicollis. Ridgely & Gwynne (1989) started

that coibensis have a blackish bill

and are ruddier above than cnephosus,

and also that it is the most numerous forest bird on the island, quite

different in this regard from the mainland populations. However, we now know

that Isla Coiba has some very interesting biogeography; for example, the

endemic Coiba Spinetail is most closely related to South American taxa, so we

think it is more likely that something interesting is going on with coibensis, possibly a future candidate

for species status. If daguae is

split, we think coibensis should be

tentatively retained with assimilis for

now, given that it is vocally much like the assimilis

group (see below). Some photos of this taxon are here: https://macaulaylibrary.org/asset/615988098 and here https://macaulaylibrary.org/asset/451105661

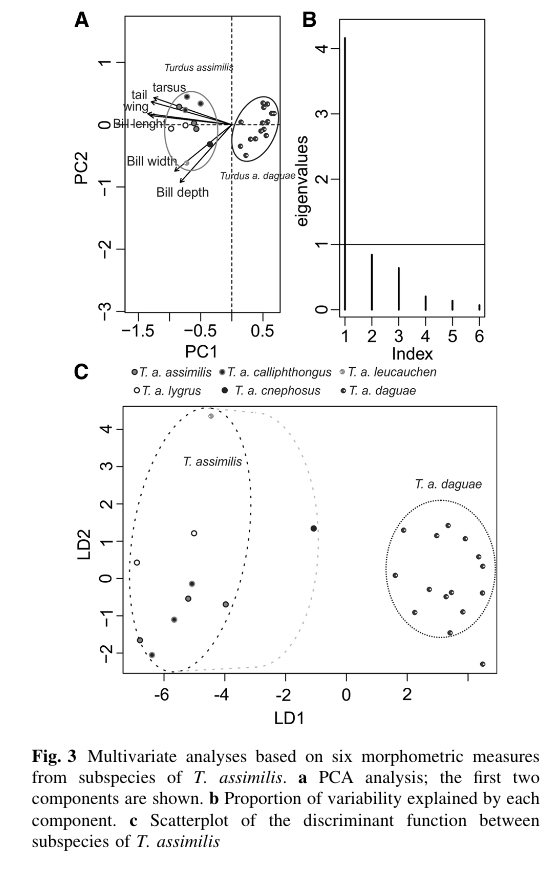

Regarding

morphometrics, Hellmayr (1934) noted that daguae

is notably smaller than other taxa. This was described in more detail in NACC

2022-A-4, but also illustrated nicely in the PCA plot from Núñez-Zapata et al.

(2016) shown below.

In

the T. albicollis complex, the main

phenotypic differences is a dark bill and gray flanks in members of the phaeopygus clade, and more yellow in the

bill and obvious rufous/cinnamon flanks in members of the albicollis clade. This pattern appears to hold even where the taxa

replace each other in Bolivia.

Vocal variation

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

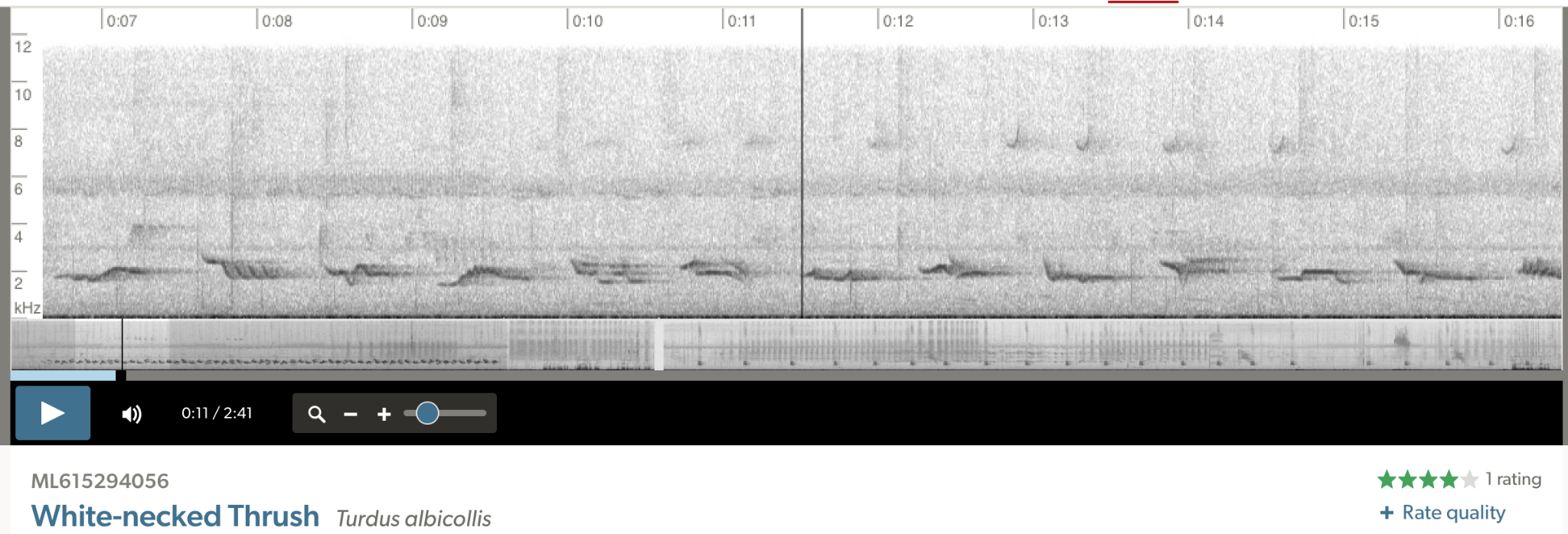

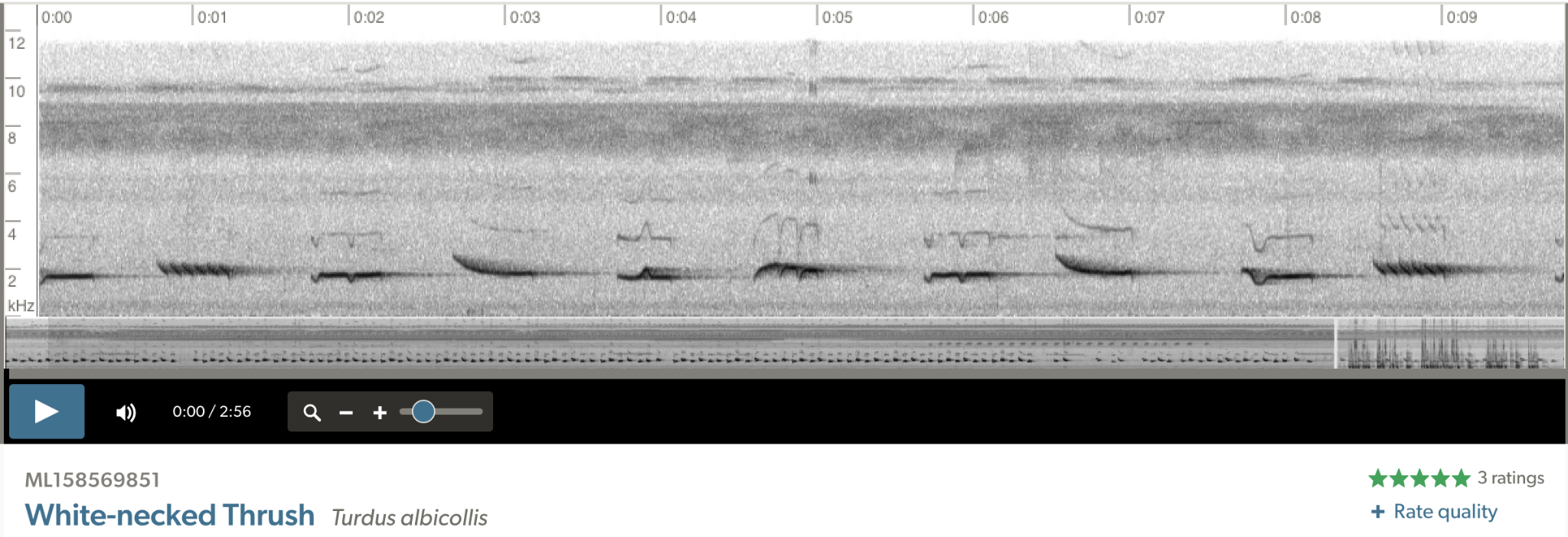

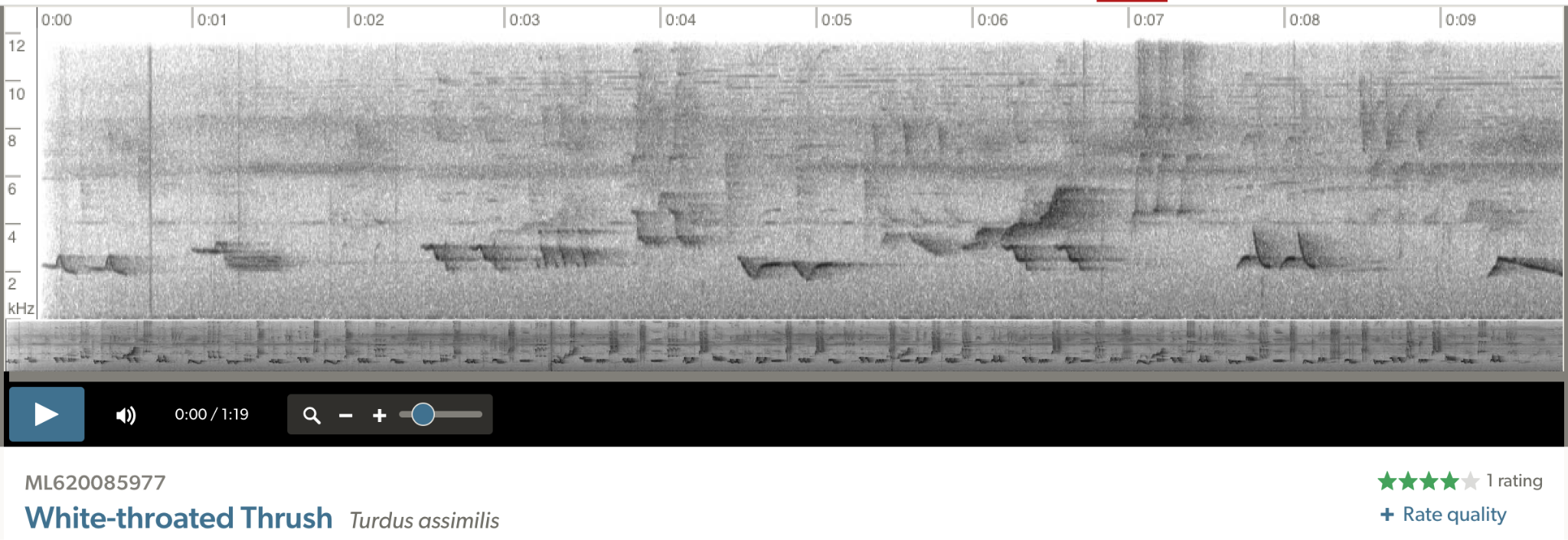

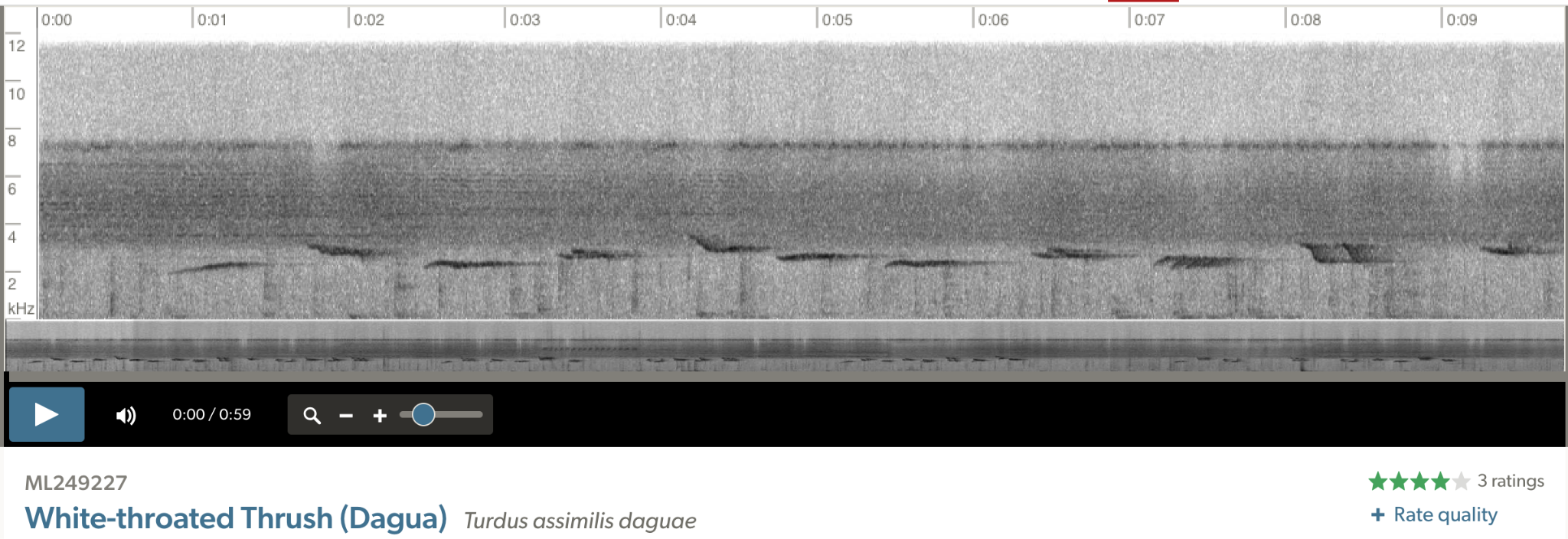

Comparisons

of song from the four major groups in the T.

assimilis / T. albicollis

complex. Top to bottom: 1) phaeopygus group,

2) nominate albicollis, 3) nominate assimilis, 4) daguae. Note the similar form and structure of daguae to T. albicollis.

Note that daguae seems to lack the

doubling of notes and the notes are more level.

To

our knowledge, the only quantitative analysis of vocal variation within the T. assimilis / T. albicollis / T. daguae complex comes from Boesman (2016), which

is worth reading: https://birdsoftheworld.org/bow/ornith-notes/JN100305

Below

are links to exemplar songs that highlight the differences mentioned by Boesman

(2016) and our comments on these differences. We note that Nacho Areta made

some excellent comments on the SACC proposal that support the distinct song of daguae. We agree that daguae sounds much more like Amazonian phaeopygus than like assimilis. Ridgely & Greenfield

(2001) had the following to say about the song of daguae: “Song a long-continued musical caroling with somewhat

monotonous effect similar to White-necked Thrush’s but pace a little faster

(very different from White-throated Thrush)”.

A

great example of most vocalizations in assimilis,

showing especially the distinctive song: https://macaulaylibrary.org/asset/72851

Here

is a good song from daguae: https://xeno-canto.org/275527 which certainly sounds

higher pitched than the rest to us and very different from assimilis. A few more examples here: https://xeno-canto.org/species/Turdus-daguae?view=3 and here:

Good

song example from phaeopygus group: https://macaulaylibrary.org/asset/158569851

Good

song example from nominate albicollis

group: https://macaulaylibrary.org/asset/615294056

The

one available song recording of coibensis

sounds typical of assimilis: https://macaulaylibrary.org/asset/69480131

Boesman

(2016) looked only at songs (which are, of course, critical), but there appear

also to be considerable differences in the calls. There are at least three main

call types in this clade: one whistled and longer, a short rough “churt” note,

and an odd chattering call.

The

whistled call note is clear and rising-falling in assimilis: https://macaulaylibrary.org/asset/231691361

But

has a rising emphasis at the end in daguae:

https://macaulaylibrary.org/asset/288967681

But

some assimilis may approach this: https://macaulaylibrary.org/asset/72851

Including

coibensis: https://macaulaylibrary.org/asset/69480121

This

call is much lower-pitched in Amazonian albicollis

(calls after 3:15 mark): https://macaulaylibrary.org/asset/188608

And

to be thorough, here is that call from nominate albicollis, which is also short and low-pitched: https://macaulaylibrary.org/asset/466693731

In

a cursory search, the short “churt” call sounds fairly similar across taxa, but

more work should be done here.

The

Amazonian taxa most commonly give the odd chattering repeated call, which is

uncommon or rare in other taxa. A good example from phaeopygus is here: https://macaulaylibrary.org/asset/245273

Here

is that call in assimilis: https://macaulaylibrary.org/asset/591450671, which sounds much

clearer and whistled than in phaeopygus,

mirroring the differences in the whistled call.

This

is the only example we can find for daguae:

https://xeno-canto.org/64330, which sounds very

different than assimilis and more

like phaeopygus, but with one

recording, it’s hard to be certain that this is a reliable difference.

The

call of coibensis is described as “a

guttural call like birds of the western highlands” and a “complaining chur-r-r or pru-rr-r” (Wetmore et al. 1984).

Distribution:

Turdus assimilis has a broad

elevational distribution, occurring in mid-elevations and low elevations from

northern Mexico through central Panama. This species is found in many foothill

localities in Costa Rica and Panama, being more widespread in the Pacific

lowlands than in the Atlantic lowlands. Farther south in this distribution, it

is found primarily at middle elevations but occasionally wanders to the

lowlands. In central Panama, it is found in the isolated hilly regions of Valle

de Antón, Altos de Campana, and Cerro Hoya (all west of the Canal zone). A few

eBird records from the Canal Zone and Cerro Azul represent the assimilis group based on photos. Ridgely

& Gwynne (1989) note that the birds in the Canal zone are wanderers from

elsewhere, with numbers peaking in November-January, and also mention that

“E.S. Morton found it to almost completely disappear from Cerro Campana during

the dry season”. So, it seems that small numbers of the foothill birds from

west of the Canal zone disperse eastward, including likely the Cerro Azul

records, and that Altos de Campana is the easternmost breeding population.

The

Pacific slope of the Darién is the northernmost extent of daguae. Wetmore et al. (1984) cite specimens from Cerros Pirre and

Tacarcuna, where they considered daguae

to be fairly common. They also mention a specimen from Cerro Sapo in the

coastal Serranía del Baudó. Ridgely & Gwynne (1989) also assign both the

Pirre and Tacarcuna birds to daguae.

In eBird, all records in the Darién south of the Chucunaque River appear to be daguae, including records in the

foothills of the Serranía de Pirre; records in the Cerro Tacarcuna lack photos.

Of interest are eBird records on the Cerro Chucantí in western Darién. Just as

we were wrapping up this proposal we noticed that a “Turdus assimilis” was marked as a background species in a recording

from this site, and it sounds to us like a typical daguae, thus extending the distribution of this taxon slightly

westward: https://xeno-canto.org/2974. Thus, it appears that

assimilis and daguae are spatially isolated by intervening lowlands in central

Panama (specifically, the lowlands around the Río Chepo),with assimilis extending as far south and

east as Cerro Azul, where they occur around 800 m, and daguae extending as far north and west as Cerro Chucantí, where

most records are > 700 m (with one record at 100 m without any

documentation). The highlands of central and southern Panama are connected by

the Serranía de San Blas, but we are not aware of records of either assimilis or daguae from this region; notably, this mountain range has a high

elevation of ~748 m, lower than the elevations of both assimilis and daguae on

the most adjacent mountains to the “gap” between these taxa and perhaps not

suitable for populations of either taxa. Thus, we find no evidence for sympatry

within the complex. .

Regarding

coibensis, Wetmore et al. (1984) cite

specimen records from some of the islands between Coiba and the mainland,

namely Isla Brincanco and Isla Rancheria, so it seems that this subspecies

approaches the mainland. However, this taxon is found down to sea level, even

in mangrove swamps, unlike foothill cnephosus

(Wetmore et al. 1984)

Possibly

of relevance, the eBird science map has different abundance patterns for the

two taxa, with daguae being uncommon

and assimilis being common. However,

there are few occurrence records for daguae,

which may impact the reliability of this difference. However, Ridgely &

Gwynne (1989) do state that daguae is

uncommon, while cnephosus is fairly

common.

In

the T. albicollis complex, most

members of the phaeopygus clade are

widely separated from those of the albicollis

clade by the cerrado of Brazil and Bolivia. However, contemptus of the albicollis

clade is found on the east slope of the Andes from southern Puno (Peru) through

most of Bolivia into extreme northern Argentina (eBird records, Birds of the

World, Herzog et al. 2016). In southern Peru and northern Bolivia, it is

parapatric (elevational replacement) with members of the lowland phaeopygus group. From the mitochondrial

phylogeny (Batista et al. 2020), the split between these two clades (albicollis and phaeopygus) is about 3.5 Mya.

Effect on SACC area:

Splitting

T. daguae from T. assimilis would result in no additional species for the SACC

area, as assimilis is extralimital.

Splitting T. phaeopygus from T. albicollis would result in one

additional species for the SACC area.

Recommendation:

Based

on differences in Cytb,

morphometrics, voice, and plumage, we posit that the T. assimilis/T. albicollis complex

as a whole comprises either one broad-ranging taxa with very

well-differentiated subspecies or four species-level taxa: T. assimilis in the north, T.

daguae in the Chocó, T. phaeopygus

in the Amazon, and T. albicollis in

southern South America. Given concordant differences in genetics, plumage, and

(in some cases) song for each of the groups, we recommend a YES vote on

elevating both daguae and phaeopygus to species rank.

Regarding

names, we suggest that the committee members read the previous NACC proposal

and comments on both the NACC and SACC proposals. Clements/eBird lists daguae as White-throated Thrush (Dagua),

and Dagua Thrush is used by Ridgely & Greenfield (2001). Hilty & Brown

(1986) also state that daguae has

been considered a separate species by others, under the name Dagua Thrush. So,

there is historical usage of this name. The name is based on the collecting

locality, the Rio Dagua, which is a fairly small river, but the name is

memorable and unique, and there is plenty of precedence for using the

collecting locality for the species name (e.g., Altamira Oriole, Tennessee

Warbler), although those names are often criticized for not being particularly

useful. Choco Thrush is a logical choice, given that it is endemic to this

biogeographic region. There are, however, plenty of other birds with the

“Choco” name, and two other Turdus

are endemic or near-endemic to the Chocó region (T. obsoletus and T.

maculirostris). However, of these three species, the range of daguae most closely matches that of the

bioregion. We therefore lean towards Dagua Thrush. This name should be

considered in consultation with NACC.

For

T. phaeopygus and T. albicollis, Clements/eBird uses

Gray-flanked for phaeopygus and

Rufous-flanked for albicollis, which

are acceptable and available names. Other options could include retaining

White-necked for albicollis and

adopting a new name for phaeopygus,

but it is not clear what other names might apply to that bird. Amazonian Thrush

is an option, as the species is widespread in the Amazon Basin, but it is one

of many Amazonian Turdus species. We

encourage SACC members to discuss potential names for these taxa.

Please

vote on the following:

A. Elevate daguae

to species rank. We recommend a YES

vote.

B. Elevate phaeopygus

to species rank. We recommend a YES

vote.

Literature Cited:

Batista, R., Olsson,

U., Andermann T., Aleixo A., Ribas C.C. and Antonelli, A. 2020. Phylogenomics

and biogeography of the world's thrushes (Aves, Turdus): new evidence for a more parsimonious evolutionary history.

Proc. R. Soc. B. 28720192400 http://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2019.2400

Boesman, P. 2016. Notes

on the vocalizations of White-throated Thrush (Turdus albicollis). HBW Alive Ornithological Note 305. In: Handbook

of the Birds of the World Alive. Lynx Edicions, Barcelona. (retrieved from

https://birdsoftheworld.org/bow/ornith-notes/JN100305).

Collar, N., J. del

Hoyo, J. S. Marks, and G. M. Kirwan (2024). White-throated Thrush (Turdus assimilis), version 1.1. In Birds of

the World (S. M. Billerman, B. K. Keeney, P. G. Rodewald, and T. S.

Schulenberg, Editors). Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, NY, USA.

https://doi.org/10.2173/bow.whtrob1.01.1

Eisenmann, E. 1950.

Some notes on Panamá birds collected by J. H. Batty. The Auk 67(3):364-367.

Hellmayr, C. E. 1934.

Catalogue of birds of the Americas, part XI. Field Museum of Natural History

Zoological Series Vol. XIII. Chicago, USA.

Herzog, S.K., Terrill,

S.T., Jahn, A.E., Remsen, Jr., J.V., Maillard Z., O., García-Solíz, V.H.,

MacLeod, R., Maccormick, A., and Vidoz, J.Q. 2016. Birds of Bolivia Field

Guide. Asocación Armonía, Santa Cruz de la Sierra, Bolivia.

Hilty, S.L., and Brown,

W.L. 1986. A guide to the birds of Colombia. Princeton University Press.

Howell, S.N.G., and

Webb, S.W. 1995. A guide to the birds of Mexico and northern Central America.

Oxford University Press.

Núñez-Zapata, J.,

Townsend Peterson, A. and Navarro-Sigüenza, A.G. 2016. Pleistocene

diversification and speciation of White-throated Thrush (Turdus assimilis; Aves: Turdidae). Journal of Ornithology

157:1073–1085. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10336-016-1350-6

Peters, J. L. 1964.

Check-list of birds of the world. Vol. X. (E. Mayr & R. A. Paynter, Eds.).

Museum of Comparative Zoology. Cambridge, Mass.

Ridgely, R.S., &

Greenfield, P. J. 2001. The birds of Ecuador. Cornell University Press.

Ridgely, R.S., &

Gwynne, Jr., J. A. 1989. A guide to the birds of Panama, with Costa Rica,

Nicaragua, and Honduras. Princeton University Press.

Vallely, A. C. and D.

Dyer. 2018. Birds of Central America. Princeton University Press.

Wetmore, A. 1957. The

birds of Isla Coiba, Panamá. Smithsonian Miscellaneous Collections, publication

4295.

Wetmore, A., Pasquier,

R. F., and Olson, S.L. 1984. The Birds of the Republic of Panamá. Part

4.-Passeriformes: Hirundinidae (Swallows) to Fringillidae (Finches).

Smithsonian Miscellaneous Collections, v. 150.

Oscar Johnson, and

Jacob C. Cooper, May 2025

Note on English names from Remsen: For daguae, if

the proposal passes I suggest we go ahead and use Dagua Thrush (see discussion

and rationale above). This is the name

already in use in several places, even going back to Hellmayr (1934) as the

name for the subspecies; thus, it is broadly acceptable, and so in the

interests of stability I see no point in trying to find a “better” name at this

point through a separate proposal. If

anyone objects to this, speak out. NACC

has already endorsed Dagua Thrush (although it is extralimital to NACC area.

For phaeopygus,

we will need a separate English name proposal, which could involve creating new

names for both daughter species. Note

the discussion above for potential names for phaeopygus and let those

incubate.

Voting Chart: https://www.museum.lsu.edu/~Remsen/SACCPropChart1044+.htm

Comments from

Bonaccorso:

“A. YES. It’s a shame there is no nuclear evidence

available, but the deep mtDNA divergence between T. daguae and T.

assimilis, along with what appear to be significant differences in song,

supports the case for treating them as separate species. I wouldn’t place too

much emphasis on the morphometric data alone, but when considered alongside the

mitochondrial genetic and vocal differentiation, it does provide stronger

support for the decision to separate these two taxa. The plumage differences

are subtle, but that is also true for the other species within the group.

“B. YES. In this case,

both mitochondrial data and UCEs (albeit with only one sample from each form)

support the separation of these two taxa. The songs also sound very different

to me—though I acknowledge that I am not an expert in bioacoustics.”

Comments from Stiles: “YES to A and B: I

consider that Elisa’s arguments sum up nicely the evidence.”

Comments from Naka:

“A) YES. I think the

evidence for splitting daguae based on phenotypical, vocal, and genetic

data are very compelling. I am happy with Dagua Thrush as the English name.

“B) YES. I like this

split, which is well supported by morphological and molecular data. I suspect

that new studies may suggest the need of further subdivisions in these two

clades, but I think it is an advancement to recognize the Amazonian and Eastern

forms as different species. As for the English names, I have nothing against Gray-flanked

for the phaeopygus group and Rufous-flanked for the albicollis group,

as suggested in the proposal.”

Comments from Rafael D.

Lima (guest voter):

“YES to A and B. While additional data are certainly needed to definitively

establish species limits within this complex, I believe the most appropriate

taxonomic treatment at present is to recognize these four groups as separate

species, given the pieces of evidence described in the proposal. It is worth

noting that the distributions of the albicollis and phaeopygus groups

may not be as allopatric as depicted in HBW/BOW or described in the proposal.

Numerous photographic records from central Brazil suggest potential contact in

that region (see https://www.wikiaves.com.br/mapaRegistros_sabia-coleira), mirroring patterns

seen in other Amazonian vs. Eastern taxa pairs (e.g., Camptostoma obsoletum

obsoletum/C. o. napaeum, Thraupis episcopus/T. sayaca,

Leistes militaris/L. superciliaris). Additionally, some authors

have proposed that T. a. contemptus may represent a hybrid population

between albicollis and phaeopygus, based on its intermediate

plumage (McCarty's 2006 Handbook of Avian Hybrids of the World, p. 238). This

seems plausible, and future sampling in all these putative contact zones will

be crucial for clarifying the species boundaries in this group.”

Comments

from Areta:

“A. Yes to T. daguae.

I was convinced of this split in the previous proposal for the reasons given in

my previous vote and continue to be persuaded after reading this proposal.

“B. I am hesitating on

this one. The deep split, plumage differences, and presumed parapatry

between contemptus (a rather grayish

or brownish-flanked western taxon of the albicollis

group) and spodiolaemus are

indicative of speciation. However, I am underwhelmed by the vocal differences,

the vocalizations are similar and clearly indicate that phaeopygus and spodiolaemus

are part of the same clade as albicollis,

at least based on their songs. What about calls? It also worries me what to do

with phaeopygoides. This taxon would

belong to the phaeopygus group based

on plumage (and geography?) but is missing vocal assessment (listen to

https://macaulaylibrary.org/asset/69474 and

https://macaulaylibrary.org/asset/177172 for example, clearly part of the albicollis/phaeopygus clade) and genetic

samples, and it would occur to the north ("northeastern Colombia to

northern Venezuela, and Trinidad and Tobago"), therefore widely separated

from the albicollis group. Because it

is largely montane, it would not fit comfortably with the "lowland

Amazonian" concept of phaeopygus

put forward in the proposal. Note also that phaeopygus

occurs across the Guianan region.”

Comments from Claramunt: “YES to both A and B. These are

clearly four well differentiated taxa. There seem to be no evidence of

reproductive compatibility or hybrids that suggest they a single species.”

Comments from Robbins: “YES, to both A & B, as all

data sets, genetic, plumage, and voice support recognition of daguae and

phaeopygus as species.”

Comments

from Remsen:

“A. YES. My previous

reservations on this split are now satisfied by additional vocal and genetic

data.

“B. NO. It is tempting

to vote yes on this one, for the reasons outlined in the proposal and also in

many of the comments, and I think the phaeopygus group will be shown

conclusively to be a good species eventually.

The data are indeed consistent with species rank for the most part,

although the plumage differences have no bearing on species rank because

different subspecies also have to have diagnostic plumage differences. The vocal data are weak and are screaming for

a forma analysis of songs and calls. The genetic results are based on a single

sample each of phaeopygus and spodiolaemus. As Nacho pointed out, phaeopygoides was not sampled vocally or

genetically. Andean contemptus also needs to be included in

these analyses; Nuñez et al. had samples, so why were these not also included

in Batista et al.? The presumed cases of parapatry could use a more through

analysis, especially because they would be indisputable evidence for species

rank if thoroughly documented. The

proposal did a great job of trying to patch the holes in the data to propose a

coherent taxonomy, but there are just too many holes, in my opinion, to make a

major change to the status quo. What’s

the rush? Let’s make sure we have it

right.”

Comments

from Zimmer:

“A) “YES. The case for splitting daguae from assimilis,

based upon genetic data (deep mtDNA divergence); song differences, which,

although not quantified in any comprehensive analysis, are qualitatively

obvious to the human ear, and visually distinct in spectrograms; and phenotypic

differences in plumage and morphometrics; are compelling.

“B) “YES. Van makes some good points regarding the weak

points in the data sets, and I agree with Nacho that the song differences

between phaeopygus and albicollis are underwhelming. However, the distinctive chattering call that

is common in phaeopygus is not something that I hear from Atlantic

Forest albicollis, which, in my experience, give the repeated short call

(e.g. https://macaulaylibrary.org/asset/466693731), both as spontaneous

calls, and, in response to playback.

That, combined with the mtDNA & UCE data supporting deep divergence

between all 4 clades (assimilis-group, daguae, phaeopygus-group,

and albicollis-group); obvious and consistent plumage and bare parts

differences; and the presumed parapatry between contemptus and spodiolaemus,

as well as the possible parapatry in central Brazil alluded to by Rafael Lima,

are enough to sway me. Obviously, more

data are needed, particularly from potential contact zones, to fully resolve

species-limits in the whole assimilis-albicollis complex, and I would

especially like to see the status of contemptus and phaeopygoides

clarified (as well as that of coibensis, even though it is outside of

our purview). Like Luciano, I suspect

that additional research will not only confirm the current proposed splits but

will also support further splits within the complex. But for now, I think the proposed splits

better reflect the relationships based on the evidence in front of us.”

Comments from Lane: “A) YES. B) YES. I understand the reservations of Van and Nacho, but

to me, the voices of the two taxa I know best (spodiolaemus and contemptus) are so different from one another, that they are clearly not

conspecific in my mind. More eastern albicollis is perhaps a bit closer to the Amazonian group’s voice, but the calls,

as Kevin mentions, still distinguish it from them easily. Overall, between

size, plumage, and voice, the southeastern T.

albicollis (including contemptus) and the Amazonian phaeopygus (including spodiolaemus and phaeopygoides) are plenty distinct and if daguae is to be recognized, I think the evidence available requires these to

be as well.”