Proposal (644) to South American Classification Committee

Revise

the classification of the Phoenicopteridae

The flamingos are a well-defined and

small family without major controversies in taxonomy. One open question had

been whether to afford species status to American Flamingo Phoenicopterus ruber versus Old World roseus, the SACC voted to accept species status for ruber in proposal 274.

Two other open questions have been (1)

whether the genus Phoenicoparrus

should be retained, and (2) the proper linear sequence in this small family. Phoenicoparrus is defined by a “deep

keeled” bill structure quite different from Phoenicopterus

and a lack of a hind toe, among other features. The importance of these

features in designating a separate genus has been questioned, although

seemingly no one has questioned the sister relationship between jamesi and andinus. Sibley & Monroe

(1990) merged Phoenicoparrus into Phoenicopterus based on small genetic

distances among all flamingos as measured by DNA-DNA hybridization (Sibley

& Ahlquist 1989).

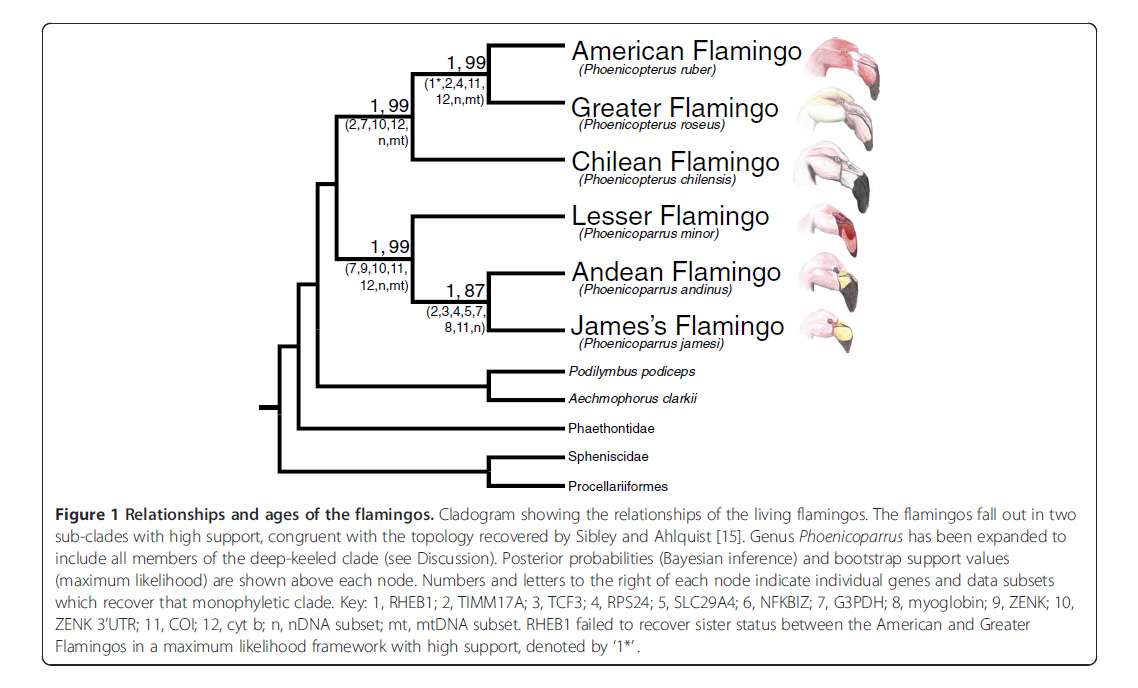

New information: Torres

et al. 2014 (http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2148/14/36)

sampled all of the extant flamingo species, including both ruber and roseus. Data

for 12 nuclear loci, and 2 mitochondrial loci were extracted for analysis. They

generated a robust phylogeny with high level of bootstrap support. They also found

that the division between American and Greater flamingoes is relatively old, as

old as between James’s and Andean, so they are well differentiated, supporting

the SACC decision to separate American Flamingo as a species.

Phoenicoparrus: They found

a deep separation between the deep-keeled and shallow keeled-flamingos,

supporting the division of the family into at least two genera. Although

outside of our region of interest, they decided to merge the Lesser Flamingo (P. minor) into Phoenicoparrus rather than retaining three genera in the family.

Proposal

A. Merge Phoenicoparrus into Phoenicopterus

As noted above, Sibley and Monroe

(1990) merged these two genera based on a short genetic distance between them,

and presumably also because the overall morphology of the two groups is very

similar other than differences in bill structure and presence/absence of the

hallux.

Proposal

B. Modify linear sequence of species

Our current linear sequence is:

PHOENICOPTERIDAE (FLAMINGOS)

Phoenicopterus ruber American Flamingo

Phoenicopterus

chilensis Chilean Flamingo

Phoenicoparrus andinus Andean Flamingo

Phoenicoparrus jamesi James's Flamingo

This needs only 1 minor tweak to

conform to our rules for sequencing. Because Chilean Flamingo is an earlier

offshoot in Phoenicopterus, it should

precede American. So the tweak would be:

PHOENICOPTERIDAE (FLAMINGOS)

Phoenicopterus

chilensis Chilean Flamingo

Phoenicopterus ruber American Flamingo

Phoenicoparrus andinus Andean Flamingo

Phoenicoparrus jamesi James's Flamingo

Recommendations:

A-

Merge Phoenicoparrus into Phoenicopterus

– I recommend a NO.

B-

Tweak the linear sequence of flamingos

to conform to the convention of least-diverse branch first. I recommend a YES.

Literature Cited

TORRES, C. R.,

L. M. OGAWAL,

M. A.F. GILLINGHAM, B. FERRARI and M. VAN TUINEN 2014. A multi-locus inference

of the evolutionary diversification of extant flamingos (Phoenicopteridae). BMC

Evolutionary Biology 2014, 14:36

SIBLEY, C. G., AND J. E. AHLQUIST. 1990. Phylogeny and classification of birds.

Yale University Press, New Haven, Connecticut.

SIBLEY, C. G., AND B. L. MONROE,

JR. 1990. Distribution and taxonomy of

birds of the World. Yale University Press, New Haven, Connecticut.

Alvaro Jaramillo, September 2014

________________________________________________________________________________________________________

Comments

from Stiles: “A. NO, in

part; the only thing I question is including minor in Phoenicoparrus

but as that is extralimital for us, we need not worry about it!”

Comments

from Remsen: “A. YES, emphatically! The paper estimates the divergence between Phoenicopterus and Phoenicoparrus as follows: “The deep- and shallow-keeled clades

diverged in either the Pliocene or earliest Pleistocene (1.7-3.9 mya).” This is

very recent for separation of genera.

For example, in the Furnariidae, the first groups that we (or anyone

previously by traditional criteria) consider as genera are at least 4 million

years old, and most are in the 8-18 mya range.

Further, I don’t know these birds very well, but at least superficially

they appear to be a single, conservative morphotype differing primarily in bill

structure (due to feeding differences).

There is no character MORE PLASTIC in morphology than bill shape – it

has long been dismissed as a character on which to base genera. Just look at Anas, Aythya, Calidris, etc., in waterbirds (much less

something like Hemignathus, which is

a young group).” B. YES. Trivial but necessary tweak to fit the

phylogeny.”

Comments

from Pacheco: “A. YES.

I agree with Van’s arguments. There are two groups, but the level of divergence

and morphological differences are not suitable for treatment in two genera. B.

YES.”

Comments

from Zimmer: “Part (A):

YES. Van’s points regarding both the estimated

time of divergence between Phoenicopterus

and Phoenicoparrus (very recent for

generic separation) and the evolutionary plasticity of bill morphology are well

taken. Part (B): YES on the necessary

phylogenetic housekeeping.”

New comments

from Stiles: A.

YES. First, after reading your comments on

the flamingo proposal, I am willing to vote against recognizing Phoenicoparrus - I hadn't caught the recency of the split,

which does indeed indicate to me that the evolution of the more specialized feeding

apparatus of the Phoenicoparrus types probably involved selection for

divergence in feeding methods vs. Phoenicopterus

types, probably due to sympatry - reflecting selection to reduce competition

and facilitate coexistence in a very special, probably limited habitat, saline

lagoons.”

Comments from Cadena: “A. NO. If we were

to start classifying these birds from scratch, then I would likely agree with

Van in that they should all probably be included in a single genus. However,

there is a tradition in recognizing two separate genera in our baseline list

and the two-genus treatment is perfectly consistent with the phylogeny, so

there is no need to change. I also agree with Van in that genera should be more

than simply clades (i.e., they should have a long history of divergence from

other clades and have meaningful phenotypic/ecological differences), but I

think stability trumps all this: we should only change when strictly necessary.

Regarding bills being highly plastic, yes, but here there is no indication that

phenotypic similarity does not reflect homology because as far as I understand

the case, the (admittedly minor) phenotypic differentiation is consistent with

the phylogeny.

B. YES.”

Comments

from Areta: “A-NO. I

agree with Van in that the bill is an extremely plastic feature, as has been

shown repeatedly. However, in this case bill-shape and presence/absence of

hallux are coincident with degree of genetic differentiation, indicating that

there is some important and consistent differentiation between Phoenicopterus and Phoenicoparrus. The fact that bills are plastic does not

necessarily mean that in all instances the differences have to do with

plasticity only. In terms of information contents, I think it is more

informative to keep two genera than to merge everything into a single one. I am

not convinced that an absolute genetic yardstick can be used to split genera,

although I appreciate deeper splits supporting generic-level taxa. Instead,

some measure of evolutionary change seems more appropriate to make the

subjective judgment of generic species limits. Alternatively, analyses of

heterogeneity can be performed to find units that may later be named genera.”