Proposal (940) to South

American Classification Committee

Recognize Pseudocolaptes

johnsoni as a separate species from P. lawrencii

Pseudocolaptes johnsoni was

described as a new species by Lönnberg and Rendahl in 1922 based on a specimen

reportedly from Baeza, Ecuador (ca. 1800 m on the Eastern slopes of the Andes).

Subsequently, Zimmer (1936) found four specimens that matched perfectly

Lönnberg & Rendahl’s description of P. johnsoni but collected

on the Western slopes of the Andes. The match was so striking that Zimmer

(1936) not only concluded that johnsoni inhabits the western slopes but

also cast doubts about the provenance of the type specimen, as all other

specimens reported from that region are clearly boissonneautii. Zimmer

(1936) also made clear that the distinctive plumage of johnsoni cannot

be confused with the juvenal plumage of boissonneautii. Zimmer ended up

considering johnsoni as a subspecies of P. lawrencii

instead, but without providing any evidence other than presumed “closer

affinities”.

Based

on plumage differences and elevational preferences Robbins & Ridgely (1990)

suggested that johnsoni deserves species status, a treatment followed by

few lists (Ridgely & Tudor 1994, Ridgely & Greenfield 2001, del Hoyo

& Collar 2016). A previous SACC proposal based on this evidence was

rejected because of lack of additional evidence such as vocalizations: https://www.museum.lsu.edu/~Remsen/SACCprop28.htm

A

more recent proposal was based on results of playback experiments showing that

the song of johnsoni does not elicit any response in lawrencii

individuals, suggesting significant vocal differences potentially producing

premating isolation (Freeman & Montgomery 2017):

https://www.museum.lsu.edu/~Remsen/SACCprop754.htm

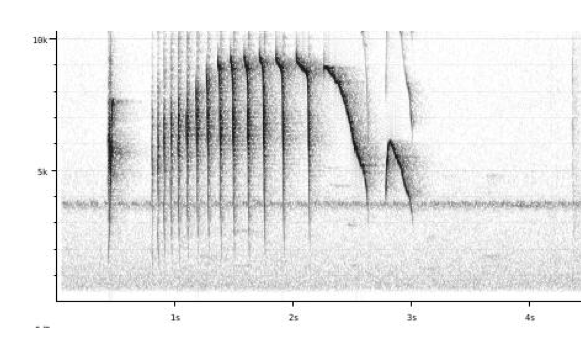

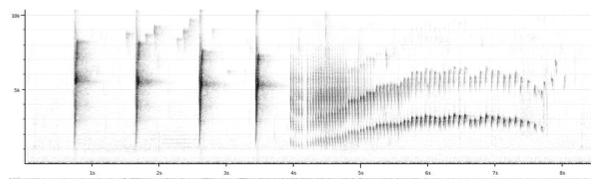

The

analyses of Spencer (2011) and Boesman (2016) show the differences in song

characteristics between johnsoni and lawrencii. If the samples

are representative of each taxon, they show well-marked differences:

“johnsoni: Song is a high-pitched rattled series

of notes slowing into stuttering and ending (always) with a characteristic

high-pitched down-slurred note.”

“lawrencii:

Song is a number of well-spaced staccato notes (always present unlike johnsoni)

followed by a trill, which usually first ascends in pitch and then slightly

descends while slowing down in pace.” (Boesman 2016)

New

Information:

Forcina

et al. (2021) revisited the issue of the species status of lawrencii by

reanalyzing DNA sequences from a previous study (Derryberry et al. 2011). They

claimed that researchers so far have “neglected” the DNA evidence that

indicates that johnsoni is a separate species. They found that the single

sample of johnsoni showed levels of divergence comparable to those

between lawrencii and boissonneautii. In other words, the three

lineages diverged nearly simultaneously about 2 million years ago (using

mitochondrial clocks; compare to ~ 4 Ma in Derryberry et al. 2011). The

analysis could not resolve whether johnsoni is closer to lawrencii

or to boissonneautii. They discuss all the evidence accumulated so far,

including morphology, vocalizations, and habitat, and conclude that johnsoni

should be elevated to species status.

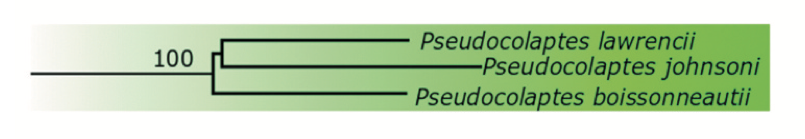

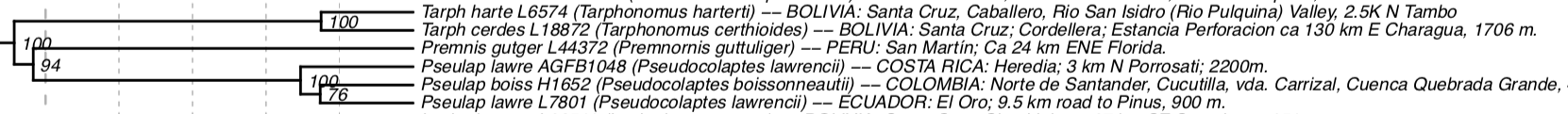

Maximum

likelihood analysis (Forcina et al. 2021 fig 1)

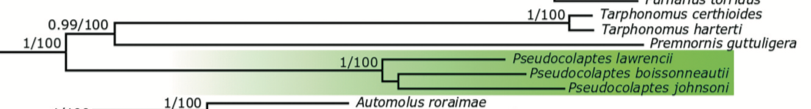

Bayesian

analysis (Forcina et al. 2021 fig 1)

Discussion:

The

data needed for evaluating the species status of johnsoni has

accumulated slowly over decades, a little at a time, mostly due to the rarity

of the species. But all pieces of evidence suggest that johnsoni is a

distinctive species. It is clearly diagnosable by plumage; it is not a cryptic

species by any means. I don’t understand why Forcina et al. claim that this is

a case of “cryptic diversity.”

Photographs

of the type specimen in the Stockholm museum are now publicly available here:

And

the photographs confirm the original description and, in my opinion, the match

between the type specimen and the AMNH series of 4 birds from W Ecuador.

Photographs

available online of live birds may be a bit confusing because of the artificial

variation in color produced by different light conditions and digital

adjustments, and the presence of birds in juvenal plumage, but here are what I

consider good representatives of adult johnsoni (very similar the AMNH

specimens):

https://macaulaylibrary.org/asset/178142751?_gl=1*1pz6d24*_ga*NjE4NTUxOTA5LjE2NDQ5NzU5MDk.*_ga_QR4NVXZ8BM*MTY0NzQwNzI3NC4yNS4xLjE2NDc0MDczMjkuNQ..#_ga=2.131747151.1345091137.1647401651-618551909.1644975909

https://macaulaylibrary.org/asset/41029281?_gl=1*30cct8*_ga*NjE4NTUxOTA5LjE2NDQ5NzU5MDk.*_ga_QR4NVXZ8BM*MTY0NzQ1Mjg5NS4yNi4xLjE2NDc0NTMwMTQuNDQ.#_ga=2.201353681.1345091137.1647401651-618551909.1644975909

In

both the holotype and the photos, note the deep rufous tones on back and flanks

(versus brown in the other two taxa), no light streaks on the mantle (vs. streaked

in boissonneautii), whitish “cheeks” (vs. buffy in lawrencii),

dark lower throat (not forming a gular band that is continuous with the light

cheeks like in the other two taxa), inconspicuous superciliary stripe (versus

thin but well-demarcated stripe in the other two taxa), blackish breast with

white rhomboid spots and rest of the belly rufous (versus predominating buffy

spots that coalesce to form a light-colored central belly in the other two

taxa).

The

song is clearly distinctive and not recognized by lawrencii in playback

experiments (Freeman & Montgomery 2017). For both plumage and

vocalizations, a more detailed analysis of geographic variation across the

Colombian Andes would have been desirable but I think that the evidence is

compelling.

Finally,

the genetic evidence adds a bit of additional information. But contrary to what

the title in Forcina et al. suggests, it doesn’t “untangle” anything. Genetic

data for just three individuals do not tell much about species limits. A random

sample of three individuals from a single large and old population can produce

a tree similar to the one found by Forcina et al. The species delimitation

algorithm based on the Poisson Tree Processes (PTP) used by Forcina et al. is

basically a mathematical formalization of a genetic divergence

threshold/yardstick criterion, in itself a rather weak species delimitation

criterion. The method classifies the nodes of the tree into speciation events

and coalescent (intraspecific) events based on levels of divergence. It thus

formalizes the observation that the three Pseudocolaptes are rather

divergent.

The

recovered topology doesn’t help much either. A strongly supported sister

relationship between johnsoni and boissonneautii would have

clearly made the case for separating johnsoni from lawrencii, but

there were conflicting topologies across methods, and clade support was nil. In

sum, the genetic data is consistent with the species status of johnsoni,

but the evidence is rather weak.

In

any case, I think that plumage, songs, and genes together provide sufficient

evidence suggesting that johnsoni deserves species-level status and

there is not a hint of evidence that suggest that johnsoni is conspecific

with lawrencii or with boissonneautii.

Recommendation:

I

recommend the treatment of johnsoni as a separate species.

Boesman, P. 2016. Notes on the

vocalizations of Buffy Tuftedcheek (Pseudocolaptes lawrencii). HBW Alive

Ornithological Note 87. In: Handbook of the Birds of the World Alive. Lynx Edicions, Barcelona.

Del Hoyo, J., & N. J. Collar 2016. Illustrated

checklist of the birds of the world, Volume 2: Passerines. Lynx Edicions,

Barcelona, Spain, & BirdLife International, Cambridge, UK.

Forcina, G., P.

Boesman, & M. J. Jowers 2021. Cryptic diversity in a Neotropical avian

species complex untangled by neglected genetic evidence. Studies on Neotropical

Fauna and Environment: 1-8. https://doi.org/10.1080/01650521.2021.1915674

Freeman, B. G., G. A.

Montgomery. 2017. Using song playback experiments to measure species

recognition between geographically isolated populations: a comparison with

acoustic trait analyses. Auk. 134(4):857–870.

Lönnberg, E., & H.

Rendahl 1922 A contribution to the ornithology of Ecuador. Arkiv för Zoologi

14(25): 1-87.

Ridgely, R. S. & P.

J. Greenfield. 2001. The birds of Ecuador. Vol. I. Status, distribution, and

taxonomy. Cornell University Press, Ithaca, New York.

Ridgely, R. S. & G.

Tudor. 1994. The bird of South America. Vol. II. The suboscine passerines.

University of Texas Press, Austin, Texas.

Robbins, M. B., &

Ridgely, R. S. 1990. The avifauna of an upper tropical cloud forest in

southwestern Ecuador. Proc. Acad. Nat. Sci. Philadelphia 142: 59-71.

Spencer, A. 2011.

Variation in tuftedcheek vocalizations. https://www.xeno-canto.org/article/99

Zimmer, J. 1936.

Studies of Peruvian birds, no. 21. Notes on the genera Pseudocolaptes, Hyloctistes,

Hylocryptus, Thripadectes, and Xenops. American Museum

Novitates 862: 1-25.

Santiago Claramunt,

March 2022

Note from Remsen on English names:

After internal discussion with SACC members, it seems best to stick with Pacific

Tuftedcheek, despite the marine connotation, because this is the name used at

the onset of the suggestions to treat this as a separate species, and because

several other bird species in the region are also referred to as Pacific

Something, with the understanding that this refers to the Pacific side of the

Andes. Therefore, we think that no

formal proposal is needed.

_______________________________________________________________________________________

Comments

from Robbins:

“YES for recognizing Pseudocolaptes johnsoni

as a species. As we pointed out in our

1990 paper, we suspected that johnsoni deserved species status based on

plumage and elevational differences. In

the original SACC proposal, I voted against recognizing it as a species because

of the lack of vocal data. However,

given that Spencer (2011) and Boesman (2016) have established vocal

differences, I now vote to elevate it to species status. As pointed out by Santiago, I consider the

genetic data equivocal.”

Comments from Stiles: “YES. As noted by Santiago,

genetics, distributions, plumage, and vocalizations all support recognition of johnsoni

as a species (the genetic evidence is weakest, but nothing suggests that johnsoni

is NOT a distinct species).”

Comments from Areta: “YES. Vocal and plumage data

support the split. The playback experiments also support this, even when these

lack rigor. Genetic data is conflicting, but show a relative deep divergence

between lawrencii, boissonneautii and johnsoni. Harvey et al. (2020) recovered a sister relationship

(with low support) of boissonneautii

and johnsoni with lawrencii sister to them:”

Comments from Lane: “YES. Between the distinctive

vocalizations and the likelihood that P. lawrencii and P. johnsoni

are not sisters, it seems the only reasonable move to separate the two at the

species level.”

Comments from Pacheco: “YES. Accumulated evidence

including genetics, morphology, vocalizations, and habitat support the

recommendation of this proposal.”

Comments from Bonaccorso: “YES. All the evidence points

towards species status. There are distinctive plumage differences between P.

lawrencii, P. johnsoni, and P. boissonneautii (still, this

level of plumage differences alone does not grant more than subspecies status

in other groups). The difference in song is clear, and the genetic

differentiation (although from just one specimen per species) is deep. Even if

we cannot know the sequence of splits between all three species, which seem to

have happened very fast in evolutionary time, the available evidence points to

three lineages that have been evolving independently from each other for about

2-4 million years. Also, I know that allopatry is frequently used against

granting species status, but I love seeing a clear geographic break between P.

lawrencii and P. johnsoni.”

Comments from Remsen: “YES, barely. I think burden-of-proof is now on treating

them all as conspecific, but not entirely because of the reasons in the

proposal. Although all the relatively

new evidence points towards recognition of johnsoni as a species, my

rationale derives from the phylogenetic hypothesis in Harvey et al. (2020), as

shown in Nacho’s comments above.

Assuming that additional taxon-sampling would not affect the topology

(see further comments below) and assuming that the weakly supported sister

relationship of johnsoni and boissonneautii has a fair chance of being correct, then treatment of johnsoni as a subspecies of lawrencii would be incorrect,

and treatment of it as a subspecies of boissonneautii is also incorrect because these two taxa are close to being

elevationally parapatric in the Western Andes without any physical barriers

between them --- those two have to be treated as separate species. Add the fragmentary vocal data to this, and

in my opinion, johnsoni has to be

treated as a species until shown otherwise.

“However, the negative wording and implications in the Forcina et

al. paper merit a critical response here lest those who don’t know the details

take them at face value. First, the

title of the paper is an in-your-face, unjustified swipe at Derryberry et al.

(2011). The title proclaims that we ‘neglected genetic

evidence’, and that Forcina et al. have come to the rescue to “untangle it”. Their abstract also proclaims:

‘We

assemble already available mitochondrial and nuclear DNA sequences to assess

their taxonomy and to provide appointed committees with specific proof [italics

inserted by me] to ascertain the number of Pseudocolaptes species.’

“Where to start?

First, Derryberry et al.’s paper was a conceptual paper in which any

taxonomic comments would have been inappropriate and edited out by reviewers,

and so this paper is not to blame for “neglecting” the issue of johnsoni. Even so, there would have been good reasons

to “neglect” the genetic data. They were

based on an analysis of 6 neutral loci of only 3 individuals, including only

1 of the 8 subspecies of P. boissonneautii. Further, the unsampled

nominate subspecies would have to be included in any analysis to anchor any

taxonomic conclusion; nominate boissonneautii is also the taxon geographically closest to the range of johnsoni, and thus its absence is an additional reason to be

cautious about the interpretation of the existing results. It would have been just as unwise for SACC or

NACC to have reached any resolution on species rank for johnsoni on such weak data

as it would have been for Derryberry et al. to have commented on it. No amount of ex-post-facto reanalysis by

Forcina et al. of DNA sequences from those three samples (the only new data

presented in Forcina et al.) will fix that crippling problem. Rather than “untangling” the “neglected”

data, their oversimplification of the problem is a potential setback. As for “proof”, the only thing they “proved”

is that they don’t understand the problems of using genetic data in a complex

system, e.g. highly polytypic P. boissonneautii is not a panmictic gene pool or that failure to include the nominate

subspecies in an analysis prevents any firm taxonomic conclusions.

“Forcina et al.’s Abstract stated:

‘However, even when multiple lines of

evidence lean toward lumping or splitting of species, some taxonomic committees

refuse to acknowledge their validity until convincing genetic evidence is produced

and integrated with other sources of data.’

“This attack on SACC and NACC requires a direct response. Contrary to Forcina et al.’s (2021)

hyperbolic claim to have restored sanity to taxonomy with resounding evidence, the

data are borderline. The plumage

differences, for example, tell us only that they are diagnosable taxa, not

necessarily species under the BSC. Many

subspecies that are more distinctive in plumage than these three taxa intergrade

at contact zones and thus show that plumage differences themselves are seldom

isolating mechanism. As for the

vocalizations, the N is small, the playbacks are not a controlled experiment,

and variation within boissonneautii and lawrencii

was noted by Spencer (2011) as adding some complexity to interpretations of

inter-taxon vocal differences:

“With such a small sample

size it's not possible for me to tell if this is a systematic difference or

just individual variation, but with what I can see it appears that populations

of Streaked Tuftedcheek vary as much vocally as Buffy do. The break appears to

be somewhere in Colombia, as at least some of the recordings from Colombia are

of the lower pitched song types, and songs I have heard in Ecuador and Peru

have also been of this type.”

“As for “refuse to acknowledge”, this reflects a misunderstanding

of the process by which those committees operate. To make a change in the classification

requires a proposal, which then has to be approved by a 2/3 majority. SACC rejected an earlier proposal before the

online summaries of vocal information by Spencer and Boesman. The “johnsoni problem” has been on our

publicly available list of proposals to be done for at

least a decade. As noted above, the

genetic data of Derryberry et al. and Forcina et al. is far from “proof” of

species rank for johnsoni, yet I pressured Santiago to write up a SACC

proposal. Does this constitute being

labeled as “refuse to acknowledge”?

“Forcina

et al. also stated:

“Derryberry

and coauthors did produce genetic data from an individual of the contentious P.

johnsoni but did not use such information in their phylogeny nor for any

comparative analyses. In spite of the overt differences in phenotypes, the SACC

(South American Classification Committee) along with the NACC (North American

Classification and Nomenclature Committee) of the AOS (American Ornithological

Society) and, as a consequence, the eBird and Clements checklists still treat P.

johnsoni and P. lawrencii as conspecifics.”

“First,

the taxon johnsoni has been treated as a subspecies of lawrencii for a century or so, including by Dickinson (2003), which is clearly

indicated as the starting point for the first SACC classification. And as Forcina et al.

noted later in their paper, a previous SACC proposal in 2003 rejected treatment

of johnsoni as a species because it was largely based

on anecdotal information. Second, “overt

differences in phenotype” are not sufficient grounds for treatment as a

separate species under any BSC-based classification, so the relevance of that

point is uncertain. Further, although

lacking modern analyses (see caveats in Remsen 2003 HBW Furnariidae account),

the 8 subspecies of P. boissonneautii also purportedly

have “overt phenotypic differences” among them --- otherwise, they would not be

treated as subspecies.

“Forcina

et al. then stated:

‘In

this study, we assemble available genetic data as a completion of multiple

lines of evidence to provide taxonomic committees with all the tools needed for

making a sound decision about the number and identity of Pseudocolaptes species,

thus eliminating the confusion arising from conflicting taxonomic treatments

and assisting future conservation actions.’

“This

over-confidence is unwarranted. The data

are still weak, with gaping holes and small N.

My vote on this is a tenuous YES only because continued inclusion of johnsoni

as a subspecies of lawrencii cannot be justified by the data in Harvey

et al. (2020), which was itself “neglected” by Forcina

et al. (published online in July 2021).

Also, I have confidence in the experience of Spencer and Boseman in

evaluating species-level vocal differences, although I worry that until all 8

subspecies of boissonneautii are included in vocal comparisons, we may

be premature in assessing vocal variation as well.

“Finally, Forcina et al. put SACC, NACC, and

Derryberry et al. on the defensive because their non-recognition of johnsoni as a species is implied

to be an obstacle to conservation.

However, the Chocó region has been recognized as a region of high

endemism for over a century (since Frank Chapman’s monographs) and as a

biodiversity hotspot since the term was invented decades ago. Whether johnsoni is recognized as a species does not affect those conclusions, much

less act as some pivot point, and any conservation measures that affect this

region will also affect johnsoni. Finally, in a seminal analysis

of Neotropical regions of endemism (Cracraft 1985 paper in the “Eisenmann” AOU Monograph volume), subspecies as well as

species were used to define those regions of endemism, as was done also in

Chapman’s monographs; thus, the taxonomic rank does not prevent johnsoni from being included

in analyses of endemism, nor does the current SACC-NACC treatment prevent

conservation measures from treating johnsoni as a species given that BirdLife International has treated it as a

species since 2016.”

Comments

from Jaramillo:

“YES – the vocal data help here.”