Proposal (969) to South

American Classification Committee

Note from Remsen: This proposal is circulating concurrently at NACC; I

have made minor editorial changes in this version.

Revise the taxonomy of Amaurospiza seedeaters:

(a) treat Amaurospiza

relicta as a

separate species from A. concolor,

and (b) treat A. concolor and A. carrizalensis as conspecific

with A. moesta,

or (c) treat A. aequatorialis as a separate species from A.

concolor,

or (d) lump the five taxa as subspecies of A. moesta

Description of the

problem:

This

proposal seeks to revise the taxonomy of Amaurospiza

seedeaters and contribute to the efforts of the Working Group on Avian

Checklists (WGAC) in reconciling global checklists. The genus Amaurospiza, as currently recognized, is

comprised of five taxa of blue seedeaters that show minor differences in

plumage coloration and body measurements. Recognition of the five taxa as

species or subspecies, including the species to which a subspecies belongs, varies

among global avian checklists (Table 1). Howard & Moore and eBird/Clements

coincide in the three species they recognize (concolor, carrizalensis, moesta), HBW-BL recognizes two species (relicta, moesta), and IOC recognizes four species (concolor, aequatorialis, carrizalensis, moesta). Classification by the NACC and the SACC agrees with Howard

& Moore and eBird/Clements.

Table 1. Current taxonomy of Amaurospiza seedeaters in four global

avian checklists. Classification by the NACC and the SACC agrees with Howard

& Moore and eBird/Clements.

|

Taxa |

Howard & Moore + eBird/Clements |

HBW-BL |

IOC |

|

relicta (Griscom, 1934) |

A. concolor relicta |

A. relicta |

A. concolor relicta |

|

concolor Cabanis, 1861 |

A. concolor concolor |

A. moesta concolor |

A. concolor concolor |

|

aequatorialis Sharpe, 1888 |

A. concolor

aequatorialis |

A. moesta

aequatorialis |

A. aequatorialis |

|

carrizalensis Lentino &

Restall, 2003 |

A. carrizalensis |

A. moesta

carrizalensis |

A. carrizalensis |

|

moesta (Hartlaub, 1853) |

A. moesta |

A. moesta moesta |

A. moesta |

The

five taxa in the genus Amaurospiza

are allopatric and distributed from central Mexico to northeastern Argentina

(Table 2). Two of the three subspecies within A. concolor (relicta and concolor) occur in the area covered by

the NACC, from central Mexico to Panama. The third subspecies of A. concolor (aequatorialis), and the species A.

carrizalensis and A. moesta, are found in South America, and,

therefore, are under the jurisdiction of the SACC.

Table 2. Geographic distribution of Amaurospiza seedeaters.

|

Taxa |

Distribution |

NACC |

SACC |

|

relicta |

Mts. of s Mexico

(s Jalisco to Guerrero, Morelos and Oaxaca) |

A. concolor Blue

Seedeater |

|

|

concolor |

Mts. of s

Mexico (Chiapas) to Nicaragua, Costa Rica and Panama |

A. concolor Blue

Seedeater |

|

|

aequatorialis |

Mountains of

SW Colombia (Nariño) to n Peru (Cajamarca) |

|

A. concolor Blue

Seedeater |

|

carrizalensis |

N Venezuela

(lower Río Caroni in Bolívar) |

|

A. carrizalensis Carrizal

Seedeater |

|

moesta |

Locally from

se Paraguay to e Brazil and ne Argentina (Misiones) |

|

A. moesta Blackish-blue

Seedeater |

Background:

Amaurospiza seedeaters are

Neotropical resident species generally associated with bamboo thickets and

dense understory (Lopes et al. 2011). They feed on arthropods and bamboo seeds,

flowers, petioles, and buds (Areta et al. 2023); in Costa Rica they prefer

greener and healthier leaves (Figure 1, Pablo-Castillo 2018).

Figure 1. Male of Amaurospiza concolor feeding on bamboo leaves in Costa Rica

(Pablo-Castillo 2018).

The

taxa within the genus Amaurospiza

have a convoluted history. Here is a brief summary of the five Amaurospiza taxa:

concolor

The

genus Amaurospiza was described along

with the species A. concolor based on specimens from Costa

Rica (Cabanis 1861). Ridgway (1901) measured one Panamanian specimen from the

Salvin-Godman collection; he noted that the species was found in both Costa

Rica and Panama.

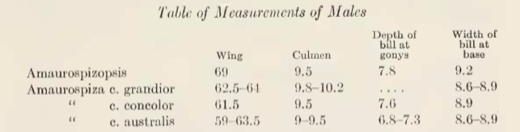

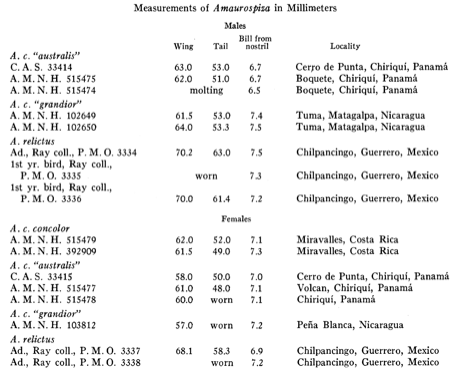

Griscom

(1934) recognized three subspecies within concolor:

concolor from northwestern Costa Rica

(Miravalles and Tenorio); and two additional subspecies that he proposed: grandior from the humid Caribbean forest

of eastern Nicaragua, and australis from

southwestern Costa Rica to western Panama. Griscom provided measurements of relicta (placed in Amaurospizopsis) and the three taxa within concolor (grandior, concolor, australis). He found overlap among most of the measurements with

the exception of the wing of Amaurospizopsis,

which was larger than in any of the concolor

taxa (Table 3).

Table 3. From Griscom (1934), morphometric

measurements of male Amaurospizopsis

and Amaurospiza seedeaters.

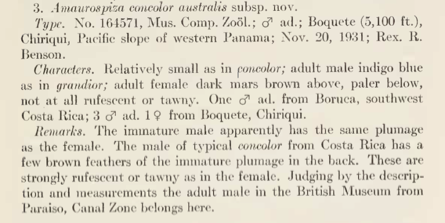

Hellmayr

(1938) noted that grandior was

indistinguishable in color from concolor,

and that only one of three specimens had a slightly longer bill, suggesting

that grandior was not maintainable as

a separate taxon. The australis group

has not been reassessed since the original description by Griscom (1934), from

which it appeared that the main difference between australis and concolor

was the plumage coloration of the immature male (Figure 2). The two taxa grandior and australis are not recognized by any of the four global checklists;

they are currently grouped within concolor

concolor (Ramos-Ordóñez et al. 2020).

Figure 2. Original description of Amaurospiza concolor australis by

Griscom (1934).

moesta

The

taxon moesta was described as Sporophila moesta with a type from

Brazil (Hartlaub, 1853). Orr and Ray (1945) noted that Hellmayr (1904) found S. moesta to be identical to Amaurospiza axillaris (Sharpe 1888).

From then on, axillaris and moesta were synonymized and have been

considered part of the genus Amaurospiza.

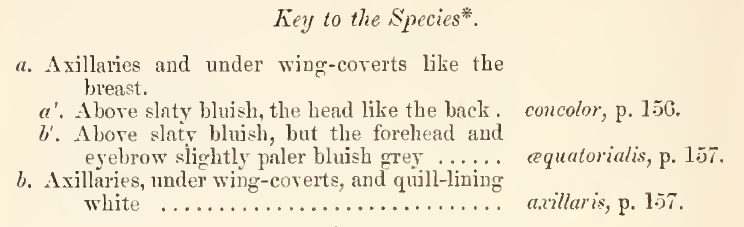

Sharpe, in a key to the Amaurospiza

species, distinguished this taxon by its white axillaries, underwing coverts,

and quill-lining (Figure 3) [see below, that Hellmayr´s assessment indicates that

the immature male type of aequatorialis

lacks white underwing coverts as indicated by Sharpe, but that an adult male

has white underwing coverts, setting aequatorialis

apart from concolor; also see Table 4 in Areta et al. 2023]. However,

Sharpe also noted that taxa within Amaurospiza

are very closely allied, making it impossible to distinguish them from

descriptions alone. The taxon moesta

is mainly found in the Atlantic Forest, although records in pre-Amazonian

wooded habitats are recently increasing (Rising et al. 2020).

![]()

Figure 3. Key to Amaurospiza species from Sharpe (1888).

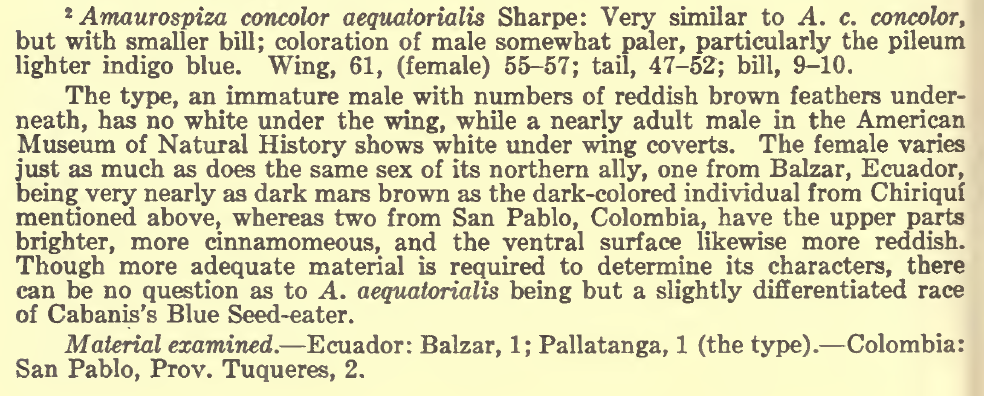

aequatorialis

Sharpe

(1888) described A. aequatorialis, a

species from the western foothills of the Andes of Ecuador, as a separate

species from concolor and moesta (under the name A. axillaris). This taxon is similar to concolor, but the forehead and eyebrows

are slightly paler bluish gray, and the bill is smaller. Hellmayr (1938)

treated aequatorialis as a subspecies

within concolor after examination of

four specimens, two from Ecuador and two from Colombia, and noted that aequatorialis was slightly smaller and

paler than concolor (Figure 4).

Figure 4. Note about Amaurospiza concolor aequatorialis by Hellmayr (1938).

AOU/AOS

considered aequatorialis as part of

the group A. c. concolor (AOU 1983;

AOU 1998). Although aequatorialis is

not mentioned explicitly in the checklist, the geographic distribution of A. c. concolor encompasses southwestern

Colombia and northwestern Ecuador. Recently, the taxon aequatorialis has also been recorded from northwestern Peru (Angulo

Pratolongo et al. 2012; Sánchez et al. 2012).

relicta

Griscom

(1934) described a new species within a new genus, Amaurospizopsis relictus, based on a specimen from Chilpancingo,

Guerrero, Mexico.

Hellmayr

(1938) suggested that relictus could

be a northern subspecies of concolor,

very similar in coloration, but with relictus

slightly larger with a deeper, stubbier bill.

Orr

and Ray (1945) compared Amaurospizopsis

and Amaurospiza, concluded that the

differences were not sufficient to warrant separate genera, and proposed that Amaurospizopsis be considered a synonym

of Amaurospiza. Griscom, in a letter

from 1944, concurred with Orr and Ray, mentioning that his views on avian

genera had changed since he proposed the genus Amaurospizopsis.

Orr

and Ray (1945) tentatively considered relictus

as a separate species, mainly due to the geographic hiatus between relictus and concolor, and the absence of intergradation in the specimens they

examined. They noted that in the length of the wing and the tail there is no

overlap between A. relictus and A. concolor, although the length of the

bill is the same for both species (Table 4). They reported that the color in

the adult male of relictus is grayer

and duller than the adult males of concolor.

Table 4. From Orr and Ray (1945), morphometric

measurements of Amaurospiza seedeaters.

Miller

et al. (1957) noted under A. concolor

relicta: “Measurements of relicta … essentially bridge the size

gap between this form and A. c. concolor

of Central America and the color differences appear to be of a magnitude

frequent in races.”

AOU/AOS

considers relicta as a group within A. concolor (AOU 1983; AOU 1998). The

sixth edition (AOU 1983) noted: “The two groups are sometimes

recognized as distinct species, A.

relicta (Griscom, 1934) [Slate-blue Seedeater] and A. concolor [Blue Seedeater]”. The seventh edition (AOU 1998) mentioned the

two groups without referring to the possible recognition of two distinct

species.

Some

authors treat relicta as a separate

species (Eisenmann 1955; Davis 1972; Howell and Webb 1995). The song of relicta is described as similar to concolor but slightly higher and faster

(Howell and Webb 1995). Lentino and Restall (2003), considering bill shape,

size, color, and song differences, suspected that relicta might represent a separate species from concolor.

HBW-BL

split A. relicta from A. concolor based on the following

rationale:

“[relicta]

commonly treated as conspecific with A.

concolor; differs (in this analysis rictal bristles and nostrils accorded

equivalence of plumage characters) by its slate-blue vs. dark blue plumage in

male (2); longer rictal bristles (Griscom 1934) (allow 1); operculate nostrils

(Griscom 1934) (allow 1); shorter, deeper bill (allow 1); longer wing and tail

(mean of 3 male tails 57.7 mm vs mean of 5 males 50.8; allow 2); “slightly

higher and faster” song (Howell and Webb 1995) (at least 1).”

carrizalensis

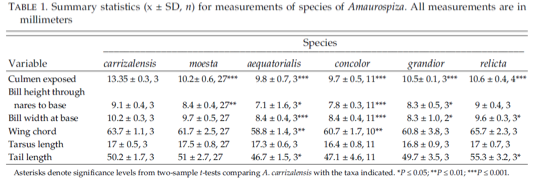

The

taxon carrizalensis was described by

Lentino and Restall (2003) based on specimens collected on the river island

Carrizal in eastern Venezuela. The authors measured their specimen series and

specimens from the other taxa within the genus (Table 5). They found that carrizalensis has the longest bill and

most pointed wing of all the taxa within Amaurospiza.

Lentino and Restall diagnosed carrizalensis

as “separable from other members of the genus by the density of coloration and

black flammulations on the breast, overall size, wing formula, volume and shape

of the bill, and general measurements”. Lentino and Restall suggested that carrizalensis should be considered a

separate species, which was accepted by the SACC due to the large range

disjunction and morphological differences from concolor and moesta

(Proposal 74, https://www.museum.lsu.edu/~Remsen/SACCprop74.htm). Subsequently, the

English name Carrizal Seedeater was adopted by the SACC (Proposal 92, https://www.museum.lsu.edu/~Remsen/SACCprop92.htm).

Table 5. From Lentino and Restall (2003),

morphometric measurements of Amaurospiza seedeaters.

Additional

notes that involve more than one of the five taxa

Hellmayr

(1938) recognized three species: Amaurospizopsis

relictus, Amaurospiza concolor

(including grandior, concolor, aequatorialis), and Amaurospiza

moesta.

Orr

and Ray (1945) proposed that two races of Amaurospiza

concolor should be recognized: concolor

from Central America and aequatorialis

from northern South America. They added that further collecting efforts may

show relictus as a large, pale,

northern race of concolor.

Monroe

(1968) noted that, in Honduras, concolor

is a rare resident of the Caribbean lowlands, where it inhabits open rain

forests, forest edges, and second growth. Monroe examined a series of relicta and concluded that the Honduran

exemplars of concolor are not

conspecific with Mexican relicta.

Honduran concolor and relicta differ in morphology and

habitat, given that relicta inhabits

mountain ranges. However, the currently known elevational range of concolor in Central America is 600-2500

m (Howell and Webb 1995), which includes elevations similar to those inhabited

by relicta.

Paynter

(1970) recognized two species: Amaurospiza

concolor (relicta, concolor, aequatorialis) and A. moesta.

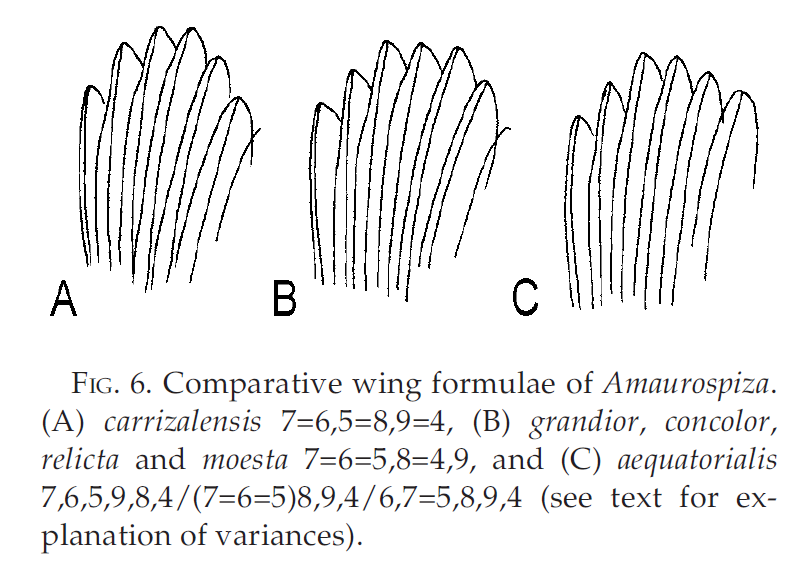

Lentino

and Restall (2003) suggested that based on wing formula, plumage and

morphological differences, and geographic distribution, aequatorialis could be a distinct species from concolor (Figure 5).

Notes

from HBW-BL: “plumage and mensural

differences are all minor, with the possible exception of the larger bill of carrizalensis;

moreover, new records from Brazil as far N as Maranhão suggest that populations

of Amaurospiza may generally be more widespread and less disjunct

than range maps indicate, as seems often the case with bamboo specialists.“

Figure 5. Comparative wing formulae of Amaurospiza as described by Lentino and

Restall (2003).

Howell

and Dyer (2022) commented on the similarity in morphology and voice of the taxa

within the genus Amaurospiza.

However, they noted that relicta is a

distinctive taxon, endemic to Mexico, and that it has been considered a

separate species. They also considered concolor

and aequatorialis to be conspecific.

New information:

Genetics

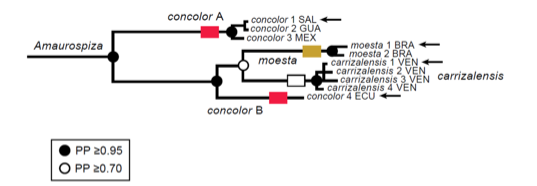

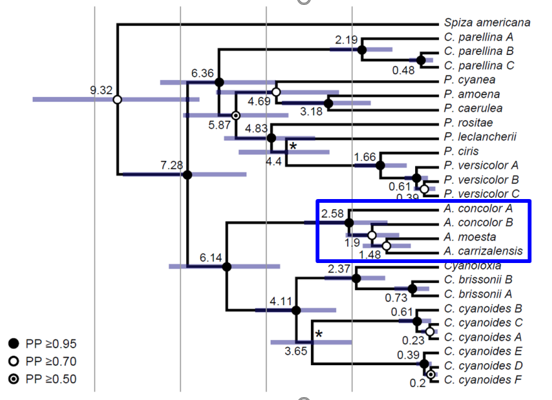

Bryson

et al. (2014) studied the diversification of the “blue cardinals” across the

New World. They generated multilocus sequence data from one mitochondrial gene

(ND2) and three nuclear introns (ACO1, MYC, FGB-I5) and estimated

time-calibrated species trees. The authors included four Amaurospiza taxa, all except for relicta. The mtDNA phylogeny recovered two main clades: a first

clade consisting of concolor (concolor) from southern Mexico and

Central America, and a second clade formed by the South American subspecies of concolor (aequatorialis), moesta,

and carrizalensis (Figure 6).

Therefore, Amaurospiza concolor was

not recovered as a monophyletic taxon, although only one sample from concolor aequatorialis was included, and

as noted before, concolor relicta was

not included. Support for the node uniting moesta

and carrizalensis was a middling PP

≥0.70, whereas support for all others was ≥0.95.

Figure 6. Relevant part of Figure 2 of Bryson

et al. (2014), mitochondrial ND2 Bayesian phylogeny.

The

multilocus phylogeny from Bryson et al. (2014) included a smaller sample size,

one individual per Amaurospiza taxa: concolor A (concolor), concolor B (aequatorialis), moesta, and carrizalensis.

However, the authors noted that it was not possible to obtain any nuclear data

for concolor B (aequatorialis), and this individual was represented only by mtDNA.

The divergence between Central American concolor

and South American aequatorialis, moesta, and carrizalensis was supported by a PP ≥0.95 (Figure 7). The nodes

within the South American clade had lower support (PP ≥0.70). Branch lengths in

Amaurospiza were comparable to

intraspecific divergence in Cyanocompsa

parellina and C. cyanoides,

although branch length between P. ciris

and P. versicolor was shorter, and

the branch length between Cyanoloxia and

“Cyanocompsa” brissonii was

comparable to Amaurospiza.

Genetic

evidence, based solely on mitochondrial DNA, suggests that concolor is more distantly related to aequatorialis than the latter is to carrizalensis and moesta;

therefore, the authors suggested that the geographically and genetically

distinctive aequatorialis be elevated

to species status (Bryson et al. 2014).

Figure 7. Multilocus *BEAST phylogeny from

Bryson et al. (2014).

The IOC list split aequatorialis

based on Bryson et al. (2014)

The SACC

assessed the split of aequatorialis

in 2016, analyzing the new phylogenetic information from Bryson et al. The

split was rejected mainly because vocal data were not published (Proposal 728, https://www.museum.lsu.edu/~Remsen/SACCprop728.htm).

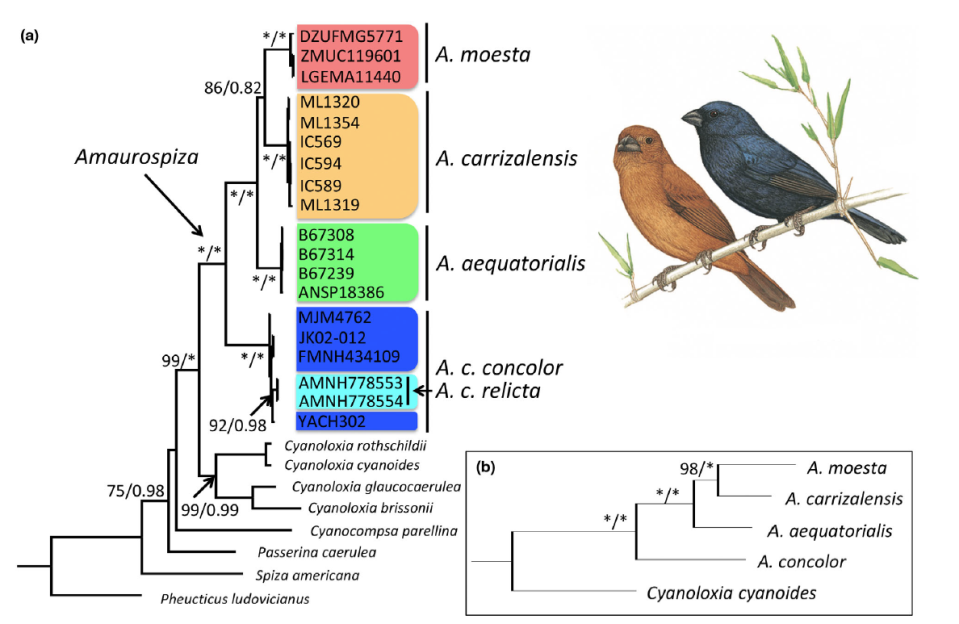

Areta

et al. (2023) developed the first phylogenetic analysis that included multiple

samples from each of the five taxa within the genus Amaurospiza. The mitochondrial gene ND2 was sequenced for all 19

ingroup samples, and three nuclear introns (ACO1, FGB5, MB) for a subset of

samples (one sample per taxon, with the exception of relicta). ND2 and multilocus phylogenetic analyses confirmed the

monophyly of the genus Amaurospiza,

recovered A. moesta and A. carrizalensis as sister species, and

supported the relationship of aequatorialis

as sister to the moesta-carrizalensis clade, thus confirming the

paraphyly of A. concolor (Figure 8).

ND2 haplotypes of relicta were

recovered as monophyletic, either within a polytomy of concolor haplotypes in the ND2 gene tree or as sister to concolor in the BEAST tree. The

relationship of concolor + relicta (ND2) or concolor (multilocus) was recovered as sister to all the other

taxa.

Additionally,

Areta et al. (2023) estimated mean ND2 pairwise distances, showing that the

distances between concolor and aequatorialis were greater (8.3%) than

those between moesta and carrizalensis (5.7%). The two relicta samples diverged on average by

1.0% from nominate concolor.

Importantly, the authors uncovered low levels of intraspecific genetic

differentiation between geographically distant populations, which contrasts

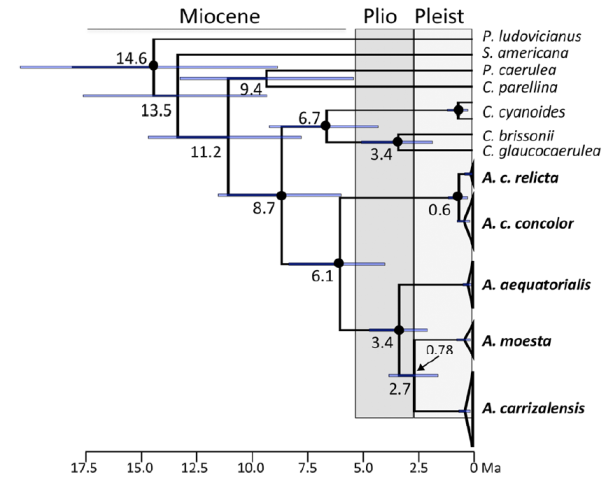

with the deep divergences between allopatric species. Divergence times

estimated from ND2 suggest that the Central and South American groups diverged

6.1 Ma, that populations of relicta

diverged from concolor about 1

million years ago, and that the differentiation of South American lineages

started about 3.4 Ma (Figure 9).

Figure 8. Phylogenetic hypothesis of

relationships within the genus Amaurospiza

from Areta et al. (2023). (a) mtDNA and (b) multilocus datasets. Numbers on

nodes represent maximum likelihood bootstrap (* 100%) / Bayesian posterior

probabilities (* 1.0).

Figure 9. Bayesian phylogenetic reconstruction

of Amaurospiza based on ND2 data from

Areta et al. (2023).

Vocalizations

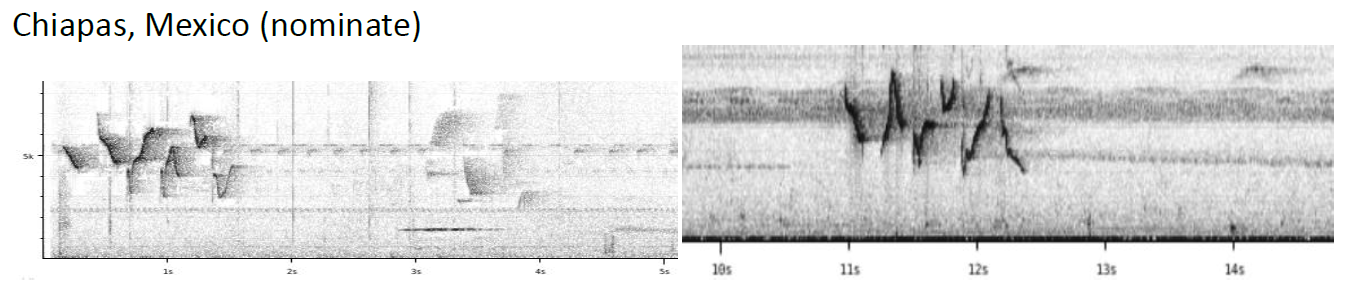

Boesman

(2016), using songs available in Xeno Canto (XC), analyzed and compared the

voices of concolor (including concolor and aequatorialis), moesta,

and carrizalensis. The taxon relicta was not included; there are no

songs available in XC or the Macaulay Library (only calls in XC). Boesman

concluded that the “song of all three species is very similar, given the range

of variation within each species”. He added:

“All basic sound parameters have a

largely overlapping range (min. frequency, max. frequency, number of notes,

note length, phrase length,...). Note shapes are also quite similar, with many

about identical between species.

“Other features that may allow differentiation such as e.g.

at start or end of a song phrase could not be found.

“It is probably impossible

to assign any recording with a reasonable level of confidence to any species. A

multivariate statistical analysis may allow to separate song of the different

taxa (once more recordings become available), but in any case differences will

be small, and will not lead to scores higher than e.g. 1 + 1 applying Tobias

criteria.”

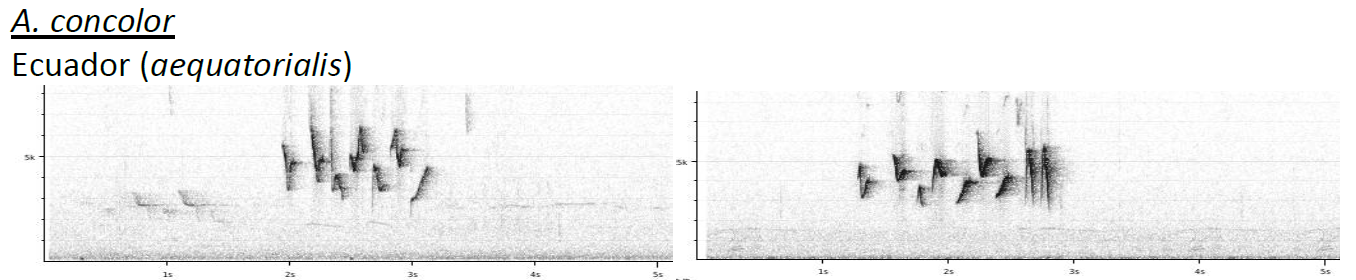

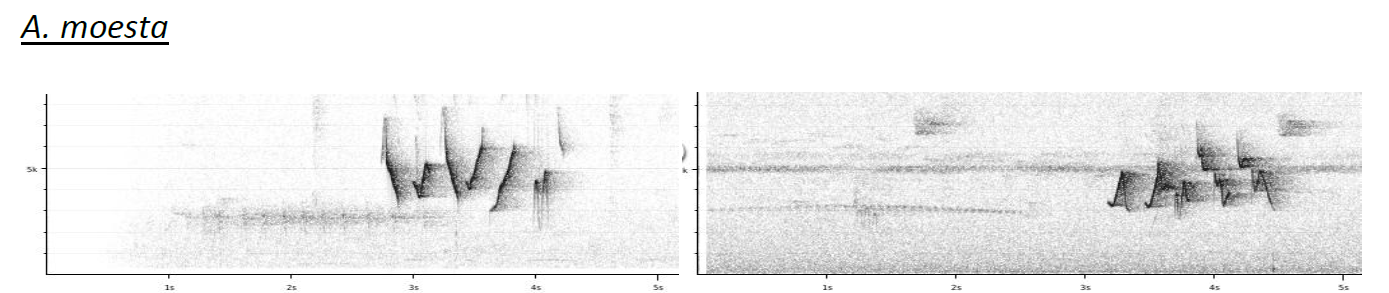

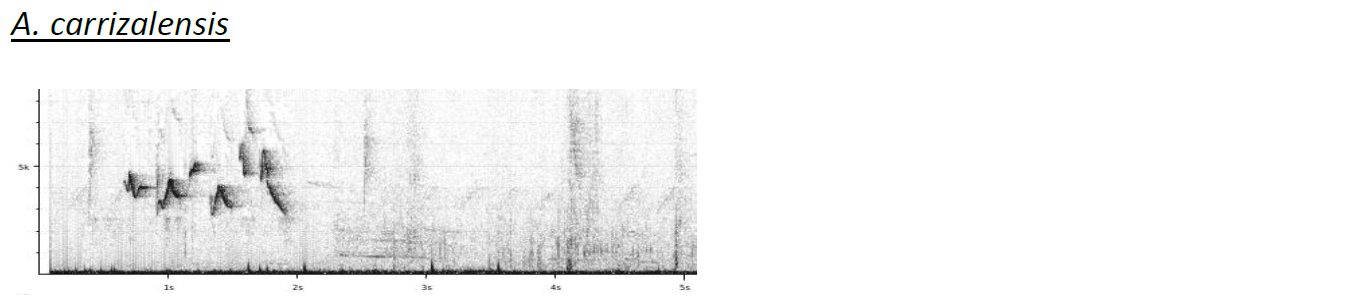

Sample of the sonograms included by

Boesman (2016):

Notes from HBW-BL: “while relicta is here separated

as a full species, the other taxa appear to be very weakly differentiated:

available acoustic evidence reveals identical songs (Boesman 2016).”

Areta

et al. (2023) performed a quantitative vocal analysis that included the five

taxa within the genus Amaurospiza.

They showed that vocalizations are quite conserved in the group, but that they

also provide taxonomically useful information. The authors found consistent

differences between the Central and the South American clades: the number of

inflections/second exhibited a stepped pattern, with concolor and relicta on

the lower end and carrizalensis, aequatorialis, and moesta on the upper end; the South American taxa averaged more

inflections per note than concolor

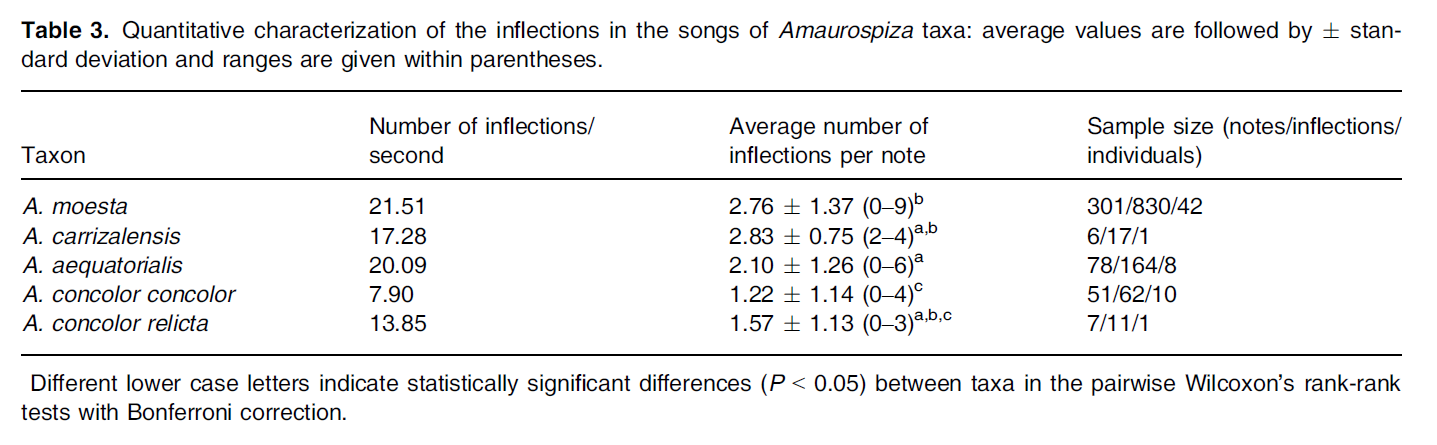

and relicta (Table 6). A linear

discriminant analysis using nine acoustic variables correctly assigned all 62

songs to the correct taxon (but note that there were single recordings for relicta [most similar to nominate concolor] and carrizalensis [most similar to moesta].

The first linear discriminant consisted mainly of maximum frequency, peak

frequency average of all notes per song, and song duration on the first three

notes; this first linear discriminant separated the South American taxa from

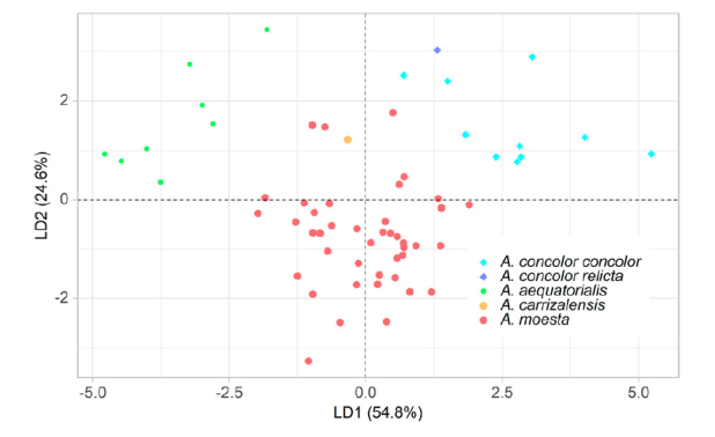

the Central American taxa (Figure 10).

Table 6. From Areta et al. (2023), quantitative

characterization of the inflections in the songs of Amaurospiza seedeaters.

Figure 10. Linear discriminant analysis of

songs of Amaurospiza seedeaters from

Areta et al. (2023). Note the distinctive cluster of aequatorialis, and the placement of the single recordings of relicta (close to nominate concolor) and carrizalensis (close to moesta).

Recommendation:

Species

limits in Amaurospiza seedeaters are

a complex issue mainly due to their morphological similarity and allopatric

distributions. Each of the five Amaurospiza

taxa is considered a subspecies in at least one of the four global avian

checklists, and each has also been considered a separate species at some point

in history. Total evidence should be considered to reconcile the taxonomy of

these seedeaters. They all are allopatric with no evidence of intergradation,

show morphological differences, have similar but distinctive songs, and are

phylogenetically closely related. The recent integrative study by Areta et al.

(2023), which analyzed phylogenetic data, vocalizations, morphology, and

plumage, suggested that four species should be recognized within the genus Amaurospiza: A. concolor (relicta + concolor), A. aequatorialis, A.

carrizalensis, and A. moesta.

We

present four separate subproposals to revise the taxonomy of Amaurospiza seedeaters:

(a)

Split Amaurospiza

relicta from Blue Seedeater A.

concolor.

(b)

Lump two

subspecies of A. concolor (concolor

+ aequatorialis) and A. carrizalensis with A. moesta.

(c)

Split A.

aequatorialis from A. concolor.

(d)

Lump the five taxa (relicta, concolor, aequatorialis, carrizalensis, moesta) as

subspecies of Amaurospiza moesta.

Approval

of subproposals (a) and (b) would reconcile NACC (and SACC) with HBW-BL.

Approval of subproposal (c) would reconcile NACC (and SACC) with IOC and

follows the recommendation by Areta et al. (2023). Approval of (a) and (c)

would result in five species; conversely, approval of subproposal (d) would

lump the five taxa in a single species, A.

moesta.

We

recommend the following votes:

(a)

NO, different lines of evidence (genetics,

plumage, morphology, and vocalization) suggest that relicta should not be given species status but considered a

subspecies of A. concolor. However,

Areta et al. 2023 recommend more rigorous studies on the taxonomic status of relicta.

(b)

NO, neither Bryson et al. (2014) nor Areta et

al. (2023) provided phylogenetic support for this lump. HBW-BL considers concolor, aequatorialis, carrizalensis,

and moesta as subspecies within A. moesta, leaving A. relicta as a separate species. However, the two large clades (relicta, concolor / aequatorialis,

carrizalensis, moesta) supported by phylogenetic data do not correspond with that

classification.

(c)

YES, all evidence support aequatorialis as a separate species from A. concolor, aequatorialis

is more closely related to carrizalensis

and moesta than to concolor, and also differs from the

latter in having white underwing coverts (at least in adult males) and in song.

Considering aequatorialis as a

separate species requires a change in the geographic distribution of A. concolor to include only the area

from Mexico to Panama (eliminating Colombia and Ecuador).

(d)

NO, phenotypic and genotypic data do not

support the lump of the five taxa within a single species.

English names:

Similarly

to taxonomic treatment for Amaurospiza

seedeaters, there is no consensus in English names among global avian

checklists (Table 7).

Table

7. English names currently used for Amaurospiza

seedeaters in four global avian checklists.

|

|

Howard & Moore |

eBird/Clements |

HBW-BL |

IOC |

|

relicta |

Blue

Seedeater |

Blue

Seedeater (Slate-blue) |

Slate-blue

Seedeater |

Cabanis's Seedeater |

|

concolor |

Blue

Seedeater |

Blue

Seedeater (Blue) |

Blue

Seedeater |

Cabanis's Seedeater |

|

aequatorialis |

Blue

Seedeater |

Blue

Seedeater (Equatorial) |

Blue

Seedeater |

Ecuadorian Seedeater |

|

carrizalensis |

Carrizal

Seedeater |

Carrizal

Seedeater |

Blue

Seedeater |

Carrizal

Seedeater |

|

moesta |

Blackish-blue

Seedeater |

Blackish-blue

Seedeater |

Blue

Seedeater |

Blackish-blue

Seedeater |

The

NACC proposal reads as follows: “Therefore, according to passing subproposals,

please consider the following:

“•

If (a) passes and relicta is

separated, Slate-blue Seedeater could be used.

“•

If (b) passes and concolor (concolor + aequatorialis), carrizalensis,

and moesta are merged, the name Blue

Seedeater could continue to be used or a new name could be proposed.

“•

If (c) passes and aequatorialis is

separated, Areta et al. (2023) suggested the English name Ecuadorian Seedeater

because most of its range occurs in Ecuador, whereas the previously proposed

name, Equatorial Seedeater, could suggest a lowland distribution rather than

the montane range that the species occupies. If you vote YES on (c), please

vote either for Ecuadorian Seedeater or Equatorial Seedeater.

“•

If (d) passes and the five taxa become subspecies within A. moesta, a new English name should be proposed.

“•

If (a) and/or (c) pass, the name Blue Seedeater could continue to be used for concolor or a new name could be

proposed.

[Note

from Remsen to SACC voters: no need to vote now, but preliminary opinions

welcomed, A separate proposal that includes all the members of our English

names subgroup is a better way to go once we have voted on species limits.]

Literature cited:

Angulo Pratolongo, F.,

J. N. M. Flanagan, W. P. Vellinga, and N. Durand. (2012). Notes on the birds of

Laquipampa Wildlife Refuge, Lambayeque, Peru. Bulletin of the British

Ornithologists’ Club 132(3):162–174.

American

Ornithologists' Union. (1983). Check-list of North American birds. 6th edition.

American

Ornithologists' Union. (1998). Check-list of North American birds. 7th edition.

Areta, J. I., Benítez

Saldívar, M. J., Lentino, M., Miranda, J., Ferreira, M., Klicka, J., &

Pérez‐Emán, J. (2023?)

Phylogenetic relationships and systematics of the bamboo‐specialist

Amaurospiza blue‐seedeaters.

Ibis (in press).

Boesman, P. (2016).

Notes on the vocalizations of Blackish-blue Seedeater (Amaurospiza moesta). HBW

Alive Ornithological Note 388. In: Handbook of the Birds of the World Alive.

Lynx Edicions, Barcelona. https://doi.org/10.2173/bow-on.100388

Bryson Jr, R. W.,

Chaves, J., Smith, B. T., Miller, M. J., Winker, K., Pérez‐Emán,

J. L., & Klicka, J. (2014). Diversification across the New World within the

‘blue’ cardinalids (Aves: Cardinalidae). Journal of Biogeography, 41(3),

587-599.

Cabanis, J. 1861. Uebersicht der im Berliner Museum befindlichen Vögel von Costa Rica, Vom

Herausgeber. Journal für Ornithologie 9: 1-11.

Davis, L. I. (1972). A

Field Guide to the Birds of Mexico and Central America. University of Texas

Press, Austin.

Eisenmann, E. (1955).

The Species of Middle American Birds. Transactions of the Linnaean Society,

Volume VII, New York.

Griscom, L. (1934). The

ornithology of Guerrero, Mexico. Bull. Mus. Comp. Zool. 75: 367–422.

Hellmayr, C.E. 1938.

Catalogue of birds of the Americas. Part XI. Field Museum of Natural History

Zoological Series, volume 13, part 11.

Howell, S. N. G., and

S. Webb (1995). A Guide to the Birds of Mexico and Northern Central America.

Oxford University Press, New York, NY, USA.

Lentino, M. and

Restall, R. (2003). A new species of Amaurospiza blue seedeater from

Venezuela. Auk 12115(3): 6115115–61156.

Lopes, L. E., De Pinho,

J. B., & Benfica, C. E. R. (2011). Seasonal distribution and range of the

Blackish-blue Seedeater (Amaurospiza moesta): a bamboo-associated bird.

The Wilson Journal of Ornithology, 123(4), 797-802.

Miller, A.H., H.

Friedmann, L. Griscom, and R.T. Moore. 1957. Distributional check-list of the

birds of Mexico. Part 2. Pacific Coast Avifauna number 33.

Monroe, B. L., Jr.

(1968). A Distributional Survey of the Birds of Honduras. Ornithological

Monographs 7. American Ornithologists’ Union, Washington, DC, USA. 458 pp.

Orr, R.T., and M.S.

Ray. 1945. Critical comments on seed-eaters of the genus Amaurospiza.

Condor 47: 225-228.

Pablo-Castillo, J.

(2018). Nuevos aportes a la ecología e historia natural del semillero

azulado (Amaurospiza concolor, Cardinalidae) en Costa Rica. Comité

editorial.

Paynter, R. A., Jr.,

Ed. (1970). Checklist of Birds of the World, vol. 13. Museum of Comparative

Zoology, Harvard University Cambridge, Massachusetts.

Ramos-Ordoñez, M. F.,

C. I. Rodríguez-Flores, C. A. Soberanes-González, M. d. C. Arizmendi, A.

Jaramillo, and T. S. Schulenberg (2020). Blue Seedeater (Amaurospiza

concolor), version 1.0. In Birds of the World (T. S. Schulenberg, Editor).

Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, NY, USA. https://doi.org/10.2173/bow.blusee1.01

Ridgway, R. 1901. The

birds of North and Middle America. Part I. United States National Museum

Bulletin 50.

Rising, J. D., A.

Jaramillo, G. M. Kirwan, and E. de Juana (2020). Blackish-blue Seedeater (Amaurospiza

moesta), version 1.0. In Birds of the World (S. M. Billerman, B. K. Keeney,

P. G. Rodewald, and T. S. Schulenberg, Editors). Cornell Lab of Ornithology,

Ithaca, NY, USA. https://doi.org/10.2173/bow.blbsee3.01

Sánchez, C., J. R.

Saucier, P. M. Benham, D. F. Lane, R. E. Gibbons, T. Valqui, S. A. Figueroa, C.

J. Schmitt, C. Sánchez, B. K. Schmidt, C. M. Milensky, A. García Bravo, and D.

García Olaechea. (2012). New and noteworthy records from northwestern Peru, Department

of Tumbes. Boletín de la Unión de Ornitólogos del Perú 7(2): 18–36.

Sharpe, R.B. 1888.

Catalogue of the birds in the British Museum. Volume XII. British Museum

(Natural History), London.

Rosa Alicia Jiménez, Terry Chesser and Juan I. Areta,

February 2023

Comments from Remsen: “Yes to the proposal’s recommendations, i.e. YES to “(c)” and NO to

a-b-d. But only because this seems to be

the best overall taxonomy given the collection of weak data we have and the

lack of stability in treatment of these taxa in various classifications. The proposal does a terrific job of

assembling every bit of published information on the group, but even combining

all this information, I see big problems.

The voices may be separable in DFA space, are those differences really

significant? DFA on the geographic

dialects of a related species, Passerina cyanea, would likely be able to

discriminate them as well. I lean more

towards Boesman’s qualitative impression that the songs are very similar,

remarkably so in my opinion given the great distances involved from one end of

this group to the other and the gaps in distribution. Playback trials would seem to be a necessary

step The genetic data are of interest, of course, but are weak in terms of

sampling of genes (mostly ND2), taxa, N, and geographic sampling with

populations. That’s not the authors’

fault – these are mostly hard-to-find, rare-to-uncommon birds – the studies did

the best they could with the material available. The minor differences in bill size, body

size, wing formulas, and coloration are all matched by intraspecific variation

in these characters in broadly distributed polytypic species of other

passerines and in themselves seem only to confirm that the taxa are

phenotypically diagnosable and thus worthy of at least subspecies rank under

the BSC. Nonetheless, some of these

differences are roughly comparable to phenotypic differences in related taxa we

rank as species, specifically Cyanoloxia cyanoides/C. rothschildii,

for which we have better data.”

Comments from Areta: “YES to C,

given the closer relationship of

aequatorialis to South

American taxa evidenced in both mitochondrial and nuclear markers, the plumage

differences, and the vocal distinctions.

NO to A, B and D. The songs of

Amaurospiza are rather

conserved, but not identical among taxa (note that there is just one recording

for carrizalensis

and one for relicta, that in

our analyses were more similar to their closest relatives). However, note that

relicta is

apparently very recently diverged from nominate

concolor (mtDNA only),

suggesting that for the time being and until there is more data, the current

evidence supports retaining it as a ssp. of

concolor. I don´t see any evidence supporting the merger of any other

taxon with moesta.”

Comments from Robbins: “Kudos to the authors of this

proposal for pulling all the information together in a digestible format. With

some hesitation, I vote YES to subproposal C, for recognizing aequatorialis

as a species, and NO to the other subproposals.

“As Van pointed out, there are issues with saying anything

meaningful about vocalizations beyond that they are very similar. Similarly,

plumage and morphometrics don’t offer much insight into this taxonomically

difficult complex. As we increasingly see, phylogenetics based solely on a

single mitochondrial gene can be misleading, but given the rather large mean

pairwise distances between aequatorialis and concolor, in

comparison to related taxa, leads me to put more weight on that factor than any

other. Hence, my vote to recognize aequatorialis as a species.”

Comments from Stiles: “The genetic data favor at least the

split of Mesoamerican concolor from South American aequatorialis,

carrizalensis and moesta and the vocal data clearly separate aequatorialis

from moesta; the separation of carrizalensis from moesta

is less clear, but given that SACC recognized it, I’ll tentatively continue to

do so as well. So, (b) NO, (c) YES, (d) NO.”

Comments from Lane: A) NO, B)

NO, C) YES, D) NO. This result seems best to reflect the molecular and voice

data presented in the proposal. These taxa are all quite rare and difficult to

document in my limited experience, so it will be a challenge to try to augment

the dataset here to see if it will change the results. I do think “Ecuadorian

Seedeater” would be an appropriate name for

A. aequatorialis. Luckily, dealing with

relicta is not our

burden to bear.”

Comments from Bonaccorso:

“969a. NO.

The data from Areta et al (2023) do not show much of a genetic difference between

A. c. concolor and A. c. relicta. Given that “The song of relicta

is described as similar to concolor but slightly higher and faster

(Howell and Webb 1995),” I don’t see much of a strong argument to split them.

Minor bill shape, size, and color differences may be just as those expected

among subspecies.

“969b. NO.

I don´t see how lumping A. moesta and A. carrizalensis makes

sense; they show almost the same amount of genetic differentiation seen between

A. moesta + A. carrizalensis and A. aequatorialis. Because

morphological differences are overlapping and song data for carrizalensis

in the LD1 is so scant, we need to go with the phylogenetic data.

“969c. YES.

Clearly, A. aequatorialis and A. concolor are not monophyletic.

So, splitting A. aequatorialis from A. concolor is the sensible

option.

“969d. NO.

For the reasons stated in the proposal (phenotypic and genotypic data do not

support the lump of the five taxa).”

Comments

from Claramunt: “YES to (c) treat A.

aequatorialis as a

separate species from A.

concolor. This is the

important piece of evidence provided by the molecular phylogeny, as pointed out

in the previous proposal 728: A. aequatorialis is not sister to concolor but to the other South American clade, and is

genetically and phenotypically (maybe in subtle ways) differentiated from all.”

“NO to

a,b,d. No evidence supports these changes.”

Comments

from Zimmer:

“Revise the taxonomy of Amaurospiza seedeaters. This is, as several others have already

pointed out, a tough one, given that sample sizes for genetic material and

vocal material are very limited, and, in general, this entire group is pretty

poorly known. But here goes…

A)

“NO.

Range disjunctions, non-overlapping morphometric characters, and

possible subtle distinctions in vocalizations all point to continued

recognition of relicta as a distinct subspecies of concolor, but

lacking genetic data corroborating greater divergence and a better sampled,

quantitative vocal analysis, I don’t think there’s enough here to support a

split.

B)

“NO

to lumping concolor + aequatorialis and carrizalensis into

moesta. This runs counter to the

genetic data, my impression of vocal differences, and ecological and

biogeographic considerations.

C)

“YES

to splitting aequatorialis from concolor, based on genetic data

(demonstrating paraphyly of concolor if aequatorialis is

included, and, the sister relationship of aequatorialis to the moesta-carrizalensis

clade), differences in underwing covert color in adult males (seemingly an

important signaling mechanism, based on how conspicuous the white underwing

“flash” is in the field for those “seedeaters” that have it), apparent

differences (no matter how subtle) in vocalizations, and biogeographic and

ecological considerations.

D)

“NO. Morphological/vocal data, genetic data, and

ecological distinctions fail to provide support for lumping the five taxa, in

my opinion.”