Proposal (978)

to South

American Classification Committee

Treat the two

subspecies of Parabuteo unicinctus as separate species

Background

and Current taxonomy

Parabuteo

unicinctus

currently consists of two subspecies, P. u. unicinctus (Bay-winged Hawk,

Temminck 1824) and P. u. harrisi (Harris’s Hawk, Audubon 1837). From 1837, these two were generally placed in

different genera (about 14 different genera) and, uncommonly, in the same genus

(Craxirex 1861-1866, Antenor 1875-1882). They were finally

stabilized in Parabuteo (1916 to

1922).

These subspecies differ by size, range, and plumage

variation. Unicinctus is distinguished from harrisi by having a dark

brown ventrum streaked or flecked with white or whitish, a smaller body and a

longer tail (Dwyer and Bednarz 2020).

Their

ranges are traditionally thought to be:

• P. u.

unicinctus is resident from ne. Colombia

and w. Venezuela south through e. Bolivia and central and ne. Brazil to

s.-central Chile and s. Argentina.

• P. u. harrisi is

resident from se. California, east to central Texas and south throughout n.

Mexico, then south along the Pacific slope from w.-central Mexico to El

Salvador and from Nicaragua to w. Colombia, w. Ecuador, and w. Peru.

New information

Clark and Seipke (2023) presented compelling new morphological

data, and they reviewed the behavioral and DNA data, all supporting the

elevation of these two subspecies to species status.

Morphological Data

Adult and

juvenile plumages differ between the two subspecies. For adult birds, these include throat markings, color

and markings on the undersides of the remiges, markings on the belly and

breast, markings on the leg feathers, and extent of white at the base and tips

of the rectrices.

In juvenile birds, consistent color differences occur in

underparts, undertail, upper back, upperwing coverts, and underwing

coverts. In addition, P. (u.) unicinctus

has delayed plumage maturation with four distinct age classes, and Clark and

Seipke (2023) provide the first detailed descriptions of Basic II and Basic

III, which are similar in body plumage to juvenile P. (u) harrisi.

See power point by Clark and Seipke.

Ecology

Harrisi individuals hunt and

breed cooperatively. Although some

examples of co-operative breeding have been noted in unicinctus, there

have been no examples noted of co-operative hunting.

DNA

Clark and Seipke (2023)

reviewed the limited DNA evidence. In a paper on Buteo phylogeny, Riesing

et al. (2003) used two mitochondrial markers (nd6 gene and pseudo-control region (ΨCR) and sequenced two unicinctus

specimens and one harrisi. Their

ML tree shows the two South American as sister to the harrisi specimen.

Raposo do Amaral et al.

(2009) sequenced mtDNA and the nuclear intron Fib5 for three Parabuteo

specimens, one from Texas and two from South America. As with the Riesing tree, the two South

American clustered together as sister taxa to harrisi.

A quick analysis of Parabuteo

cytb sequences (the three from Raposo and Lerner et al. harrisi sequence),

using Blast, resulted in two clades – the two harrisi as sister taxa to

the two unicinctus (pers. obv.).

Recommendation:

The new morphological

data and existing DNA and behavioral data support elevation of the two

subspecies and the redefinition of the ranges of the species as follows:

• P. unicinctus - resident in much of lowland tropical and

subtropical non-Amazonian South America, including west of the Andes in Chile,

Peru, Ecuador.

• P. harrisi - resident from se. California,

east to central Texas and south throughout n. Mexico, then south along the

Pacific slope from w.-central Mexico to Costa Rica.

Although the current

range of harrisi is described as occurring in northwest South America south

to northwestern Peru, new information about the Basic II and III plumages of unicinctus

suggests that these South American sightings were probably juvenile unicinctus,

because observers unaware of these plumages would be unable to distinguish them

from juvenile Harris’s Hawk. Clark and Seipke (2023) also noted that

researchers in Ecuador have not seen Harris’s there.

Current range maps and

eBird sightings for P. unicinctus show geographic separation of South

American populations from Central and North American, with a gap in

distribution in Panama. This is

consistent with an interpretation of the ranges of P. harrisi and P. unicinctus

being geographically separated.

Literature Cited

Clark, W. S. and S. H.

Seipke. 2023. Taxonomic status of Bay-winged Hawk Parabuteo (unicinctus)

unicinctus and Harris’s Hawk P. (u.) harrisi, with documentation of

delayed plumage maturation in Bay-winged Hawk. Bull BOC 143(2):142-152.

Dwyer, J. F. and J. C.

Bednarz. 2020. Harris's Hawk (Parabuteo unicinctus), version 1.0.

In Birds of the World (A. F. Poole, Editor). Cornell Lab of Ornithology,

Ithaca, NY, USA. https://doi.org/10.2173/bow.hrshaw.01

Lerner,

H. R. L., Kolaver. C. K. & Mindell. D. P. 2008. Molecular phylogenetics of

the buteonine bird of prey (Accipitridae). Auk 125: 304–315.

Raposo do

Amaral, F. R., Sheldon, F. H., Gamauf, A., Haring, E., Riesing, M., Silveira,

L. F. & Wajntal, A. 2009. Patterns and processes of diversification in a

widespread and ecologically diverse group, the buteonine hawks (Aves,

Accipitridae). Mol. Phylogenetics & Evol. 53: 703‒715.

Carole S.

Griffiths, July 2023

Comments

from Areta:

“YES. The differences in plumages of juvenile and

definitive harrisi and unicinctus are striking, and have indeed been long recognized.

Although not new to me, it is good to see the evidence for basic II and basic

III plumages of unicinctus being published and called to the attention of the

ornithological community. It is a pity that the wing molt of the specimens used

to substantiate the claims of basic II and III unicinctus is not shown in

the paper and not accurately described, and that the specimens examined in

museums have not been properly listed with their corresponding molt. The fact

that no basic II or III plumages are shown in flight in the paper itself is rather

confusing, as unaware readers may be drawn to think that birds can be properly

aged by looking at the body aspect: yet as described in the text, proper aging

is performed by looking at wing molt (something that Clark and Seipke have

championed for a long time, to be sure). I find it surprising that no attempt

was made to characterize the vocalizations of the two taxa; someone should

explore this. The limited genetic data do not provide strong support for

species status of unicinctus and harrisi, and are

compatible with different possible scenarios. However, I think that the data

collectively tip the scale to consider

unicinctus as a separate

species from harrisi, and the

burden of proof should be inverted. On a personal note, I lament that the

authors did not "find" that Pearman & Areta (Field Guide to the

Birds of Argentina and Southwest Atlantic, 2020) have also provided accurate

illustration of unicinctus (juvenile and adult). To conclude, I

vote YES to the split of unicinctus from harrisi, although I think

that a much stronger case could have been built to support this treatment.”

Comments from Stiles: “YES, in the sense that although

the data supplied by Clark & Seipke leave some notable holes, it definitely

shifts the burden of proof onto those who would maintain both groups as

subspecies under unicinctus.”

Comments

solicited from Therese Catanach: “The

fact there is some shallow population structure in a widespread species

(especially one that undergoes limited or no seasonal movement in much of its

range) is unsurprising. However, level

of genetic differentiation between the two currently recognized subspecies of Parabuteo

unicinctus is well within the range expected for intraspecific

variation. For example, 4 cyt b samples

from Parabuteo leucorrhous are also publicly available. Two of these samples, ANSP 180970 (tissue #

ANSP 660) and ANSP 186050 (tissue # ANSP 5082) are both from Ecuador and yet

exhibit similar levels of genetic differentiation (0.47% divergent) as those

observed between North (including a new cytb sequence generated by Catanach et

al. 2023) and South American populations of Harris’s Hawk (which range between

0.46 and 0.58% divergence). This level

of divergence is low when compared to other hawk species, for example a

sampling of Red-tailed Hawks show divergence as high as 1.7% when comparing

specimens collected in the United States.

When comparing these p-distances to those calculated for sister species,

Parabuteo leucorrhous and Parabuteo unicinctus are over 6%

divergent. When looking across

Buteoninae as a whole (using the data from Catanach et al. 2023), the average

cytb divergence is 2.9% divergent between sister species. Only 6 sister species are lower than 1.4%

compared to the maximum of 0.58% exhibited within the Harris’s Hawk

samples. Of these sister species pairs,

the species status of most has fluctuated in the literature (e.g. Haliaeetus

sanfordi and H. leucogaster and several Old World Buzzard

taxa). In fact, only one, the Buteo

galapagoensis and swainsoni pair is only 0.18% divergent and has not

been widely questioned. However, these

two taxa are morphologically distinct enough that a sister relationship was not

suspected until sequencing data recovered this arrangement (Bollmer et al.

2006) making it a very different situation than the two morphologically similar

Harris’s Hawk subspecies.”

Bollmer,

JL, Kimball, RT, Whiteman, NK, Sarasola, JH, Parker, PG. 2005. Phylogeography

of the Galápagos hawk (Buteo galapagoensis): A recent arrival to the

Galápagos Islands. Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution. 39 (1): 237–247.

Catanach,

TA, Halley, MR, and Pirro, S. 2023. Enigmas no longer: using Ultraconserved

Elements to place several unusual hawk taxa and address the non-monophyly of

the genus Accipiter (Accipitriformes: Accipitridae). bioRxiv

2023.07.13.548898; doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.07.13.548898

Comments

from Zimmer:

“YES,

although I don’t consider it a slam-dunk.

I’m really not all that impressed by the meager genetic data, but the

sum of fairly obvious differences in both adult and juvenile plumages, the

differences in molt sequences and number of plumage cycles between the two, and

the ecological/behavioral differences, combined with the fact that the two were

not only historically treated as separate species, but also were often treated

as belonging to separate genera, makes me think that the burden of proof should

shift to those favoring maintaining the one-species treatment. I would second Nacho’s call for a vocal

analysis to strengthen the case – I suspect that vocalizations might prove

diagnostic.”

Comments from Lane: “YES. As others state, I think

the overall amount of evidence makes this split quite reasonable. I have long

noticed that North American and South American Parabuteo differ. Even

those on the Pacific coast of Peru didn't match North American birds, so I

never understood how they could be considered harrisi? The present study

explains all this satisfactorily to me.”

Comments from Del-Rio: “NO. Although the morphological

differences exist, I am afraid the molecular differences are not compelling

enough. I will keep my standard criteria here.”

Comments from Robbins: “NO. Clearly, genetic

data do not offer support for species recognition. Moreover, like Nacho, I have issues with how

the data were (or were not) presented. Likewise as Nacho pointed out, there should

have been an attempt to ascertain whether there are differences in

vocalizations. Whether differences in

juvenile plumage merit species recognition is an open question. I vote NO for species recognition until there

is a clearer and more detailed analyses of these two taxa.”

Comments from Brian Sullivan (voting for Remsen): “The

authors should be commended for bringing this interesting and vexing taxonomic

issue back into the light. In this case, there are clearly two taxa involved—I

completely agree! But how and where those taxa come into contact, whether they

interbreed, and what their respective ranges are, all require further study. I

don’t think the proposed distribution break in Panama is the simple and clean

delineation the authors suggest it to be—at least not based on the images I’ve

found below, which show Harris’s-like birds all the way south to Ecuador in

South America, and more mixed types in Lima down through Santiago. South of

there, based on a quick look at photos in ML, it seems like most are Bay-winged

types. Everything east of the Andes seems like Bay-winged types.

“Given that I only spent an hour perusing the Macaulay Library’s

collection of these taxa, it seems relatively easy to find exceptions to the

hard and fast rules outlined in the paper, such as:

“There are no valid

records of Harris’s Hawk in South America.”

https://macaulaylibrary.org/asset/217536651

https://macaulaylibrary.org/asset/427018861

https://macaulaylibrary.org/asset/481506641

https://macaulaylibrary.org/asset/116191271

https://macaulaylibrary.org/asset/328118561

“All adult harrisi have unmarked dark

undersides to the remiges”

https://macaulaylibrary.org/asset/121846531

“whereas all adult unicinctus have whitish primaries

with narrow dark bands and black tips on the outer ones, but many adult unicinctus

have whitish secondaries with narrow dark bands (Fig. 2a), though some have

darker secondaries with some narrow white bands”

“See the many examples above that would be unicinctus

based on this proposed split that have all-dark remiges like harrisi.

“All adult unicinctus have a broad darker

subterminal band on the secondaries”

https://macaulaylibrary.org/asset/559744391

https://macaulaylibrary.org/asset/559744351

“We found no specimens

or photographs exhibiting characters of both taxa.”

“See example from Lima above.

“For now, I vote ‘NO’ on this proposed split, as I believe further

study is warranted. It could be that two species are involved, but more

information about how they interact, especially north and west of the Andes,

seems essential.”

Comments from Claramunt: “NO. I

don’t see compelling evidence for this split. The new data on juvenile plumages

by Clark & Seipke is very interesting and important; they found that the

juvenile plumage of birds from South America is different from that of birds in

Central and North America. But what is lacking for resolving this problem is a

detailed individual-level analysis of the geographic variation of the relevant

traits. That analysis would clarify whether there are two species or just a

single species that exhibits geographic variation. Framing this problem as an

issue of counting differences between two well separated taxa can be

misleading.”

“The main problem is that birds from the Pacific side of Colombia,

Ecuador, and Peru, have been considered to be harrisi, not nominate unicinctus. Clark & Seipke try to

minimize this issue by implying a “mistake” in the recent literature:

‘Some authorities (e.g., Dickinson & Remsen 2013, Clements et al.

2022) have mistakenly listed Harris’s Hawk for north-west South America.’

“In reality, most previous avian taxonomist have assigned these

populations to harrisi based on the examination of specimens that

showed uniformly dark underparts like harrisi (e.g. Hellmayr and Conover 1949, also citing

Chapman, Blake 1977). Those harrisi-like

individuals found from Colombia to Peru can be seen also in the photos posted

by Brian Sullivan.

“Therefore, birds from the Pacific side of South America seem to

show a mix of harrisi and unicinctus characteristics, exactly what would be expected

for a widespread species that has been exchanging traits via gene flow.”

Comments from Jaramillo: “NO. There does

seem to be something here that requires further work to adequately describe the

situation. Are there two, or are there three populations? The latter has not

been evaluated, but it is likely. That third Pacific population, what is it? An

intermediate, or a different population altogether, a subspecies of harrisi?

What I can say is that this species is a common hawk of Chile’s central zone,

yet in the last decade or two it has become more common in the far north, where

it is assumed that the Peruvian population moved south. To my eye, those

northern birds do not look like the true unicinctus of the south. I have

not understood exactly how they look different, but the tendency is to look harrisi

like.

“Also, it is worth noting that there are multiple gaps in the

distribution of this species, not just the one in Panama. There is an isolated

group in Colombia/Venezuela. Then we have the Pacific group that stretches from

S Ecuador to (now) northernmost Chile. But it has been and still is largely

isolated from the unicinctus of the southern cone. That gap is

narrowing. To my untrained eye, the birds in Colombia/Venezuela are harrisi.

The map shown in the powerpoint is also not correct: there is no connection of unicinctus

to the Colombia/Venezuela population via the area east of the Andes -- there

are no Parabuteo there. The fact that we have intermediate looking

birds, at least 4 isolated populations, and lots of questions means there is

more work needed.”

Additional comments from Lane: “One thing that may be confounding the issue is the

presence of escaped uncinatus in coastal Peru thanks to escaped

falconers’ birds and efforts to use hawks as pest control in agricultural areas

along the coast (this per the attached paper and

pers. comm. from Fernando Angulo). This may be changing the dynamics of which

taxon is present at least in coastal Peru. So this bit of information may be

something that clouded the distributions of the two taxa along the Pacific

coast of Peru, and perhaps elsewhere. Whether the two forms interbreed or not

would be worthy of study. Perhaps the votes on this proposal should be

postponed until such a study is run?”

Additional comments from Stiles: “Given the

multiple problems with the data of Clark & Siepke and Brian and Alvaro's

comments in particular showing various points of ambiguity, I agree that more

detailed information, largely requiring more field studies, would be needed to

fully understand this interesting problem, so I will change my vote to NO.”

Comments from Bill Clark and S.

Seipke:

“Note that there were three committee members who positively for

this split. Two of the three committee members who yoted yes mentioned the

differences in immature plumages. However, none of the six committee members

who voted no of one mentions this major difference between these taxa: the

difference in the number of immature plumages. No other of the 320+ species

diurnal raptors differs in the number of immature plumages between or among

subspecies. Surely this has a genetic basis and should be a factor in the

taxonomic decision.

“Specific comments:

“Sullivan found some photos of Bay-winged Hawks from the west of

the Andes that have uniformly dark remiges. What he did not find were any

photos of juvenile harrisi from this region. No photos exist in the Macaulay library

from Colombia to Peru that are of juvenile harrisi. All in this photo collection and museum

specimens from this region are of juvenile and Basic II & III are unicinctus. There may well be a subspecies of unicinctus

from there in which the adults have dark remiges. However, the birds west of

the Andes are not harrisi, as there are no juveniles of that taxa there,

only juveniles and Basic II & III unicinctus.

“Claramunt states that the birds from west of the Andes are harrisi,

but there are no photos or specimens of juvenile harrisi from this

region. Only adults with dark undersides of their remiges. He mentioned the

lack of individual-level analysis of the geographic variation in the paper. He

is mistaken in that every juvenile specimen or photo from South America fits

the characters of juvenile unicinctus and, likewise, every juvenile

specimen and photo from Central America north fits the characters of harrisi,

and there is no overlap in these characters.

“Jaramillo offers little in taxonomic insight other than there may

be a separate taxon west of the Andes.

“Catanach and Del-Rio think that the level of genetic differences

is too low for species, but the genetic analyses done to date are few and

shallow. Again, why did they not discuss how two subspecies can have a

differing number of immature plumages?

“Robbins questions the differences in juvenile plumage of the two

taxa, when it has been clearly shown in Clark & Seipke (2023) that they

differ greatly. The reason we did not use vocalizations is discussed below

under Areta.

“Areta (a positive vote) Mentions that Clark & Seipke (2023)

do not show Basic II and Basic II unicinctus in flight; they do however,

refer to URLs in the paper pointing to flying immature unicinctus that

show this primary molt of both ages of immatures.

“Areta suggests that vocalizations should be compared. We did

listen to some and felt that they were too similar to use for differences.

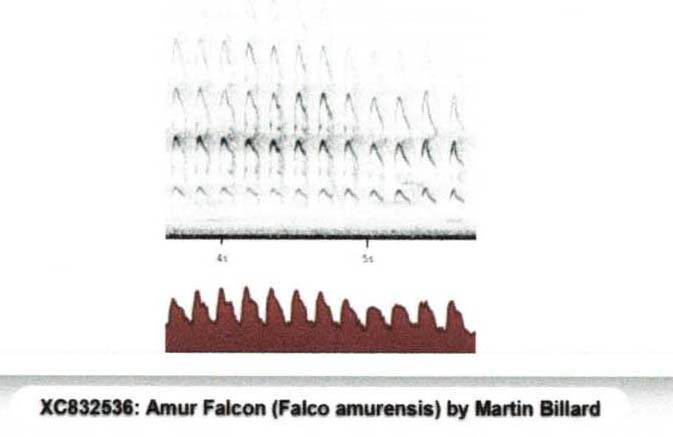

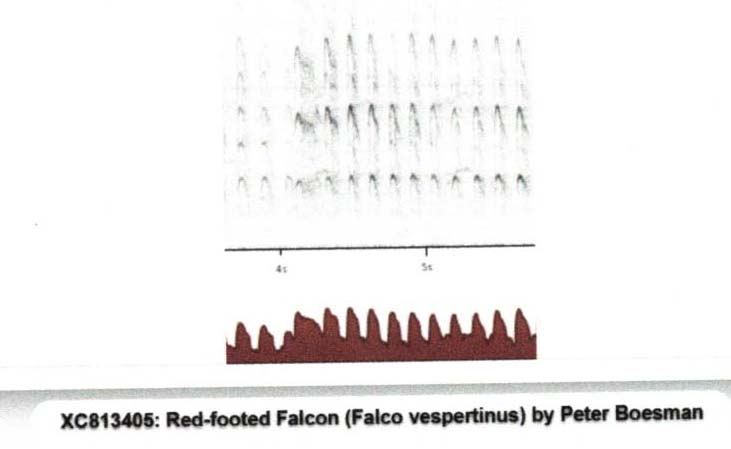

Sister species can have the same call. For Example:

• Amur Falcon

https://xeno-canto.org/species/Falco-amurensis

• Red-footed Falcon

https://xeno-canto.org/species/Falco-vespertinus

“Their calls sound the same. See also the attached sonograms

below.

“In summary, we feel that the consideration of this proposed split

by some committee members was shallow and did not take into account the great

differences in annual plumage sequences between these taxa, as well as the

great differences in plumages, especially juveniles.

“David Mindell, noted raptor taxonomist, supports our arguments

above.”

Comments from Fernando Angulo:

“I have

a couple of comments regarding the proposal and the PowerPoint presentation.

“1.

Lima’s Parabuteo unicinctus is a population formed from escaped birds

that were used by falconers, including me. We got our birds at that time, from

local trade. I am referring to years 1990 approximately, until more or less

2000 (This stopped when there were available birds from captive breeding). I myself

have contributed with at least one escaped bird. Birds that were acquired on those

days were from unknown origin (sellers told us “From the north”, referring to

Piura or Tumbes, but we have no certainty of that). So, the Lima population is

formed from unknown subspecies of Parabuteo unicinctus, basically, from

birds of unknown origin.

“2.

Distribution in coastal Peru, as far as I know, has to be taken carefully. The Lima

population is from escaped birds, which are expanding north, west, and east

from the Lima city. Also, there is a native population (you can check Koepcke’s

Aves de Lima book, where she mentions “rarely seen on the coast and Andean

slopes”). Other coastal populations can be safely regarded as wild, such as in

the dry forest of Tumbes, Piura, and Lambayeque, for example. Here, part of the

problem is that with growing agriculture activities on what was desert on the

Peruvian coast, “bird control” using trained Parabuteo unicinctus has increased

a lot, especially in Lima, Ica, La Libertad, Lambayeque, and lower Piura. This

means that any Parabuteo unicinctus found on any of the coastal cities

has to be carefully evaluated, because there is a great chance of being escaped

from trained birds.

“3.

Trained birds currently come from breeding centers that are using Parabuteo

unicinctus captured or obtained from the Lima population, or not. The Lima Parabuteo

unicinctus population originated from birds of unknown origin, and the

captive breeding centers uses birds from unknown origin (it can be from injured

birds from Lima population x a wild bird confiscated from illegal trade, or any

of the imaginable possibilities), so the Parabuteo unicinctus used for

bird control, i.e. the ones likely to be found on coastal cities, can’t be

regarded as typical looking wild birds.

“4.

A problem I see, is that several pics from Peru on the Clark & Seipke power-point

are taken by Lee Jones. Lee was a veterinarian working at El Huayco some 5 or

more years ago. We cannot eliminate the possibility that the pics he took

belong to Lima Parabuteo unicinctus (not wild birds) that are simply,

from unknown/uncertain origin or identity. So, those pics can’t be used to

separate these two spp into sp. (slides 8 and 21). On slide 21, you can notice

infrastructure of El Huayco in the background.

“5. On the other hand, I can see

plenty of birds from Peru that look more closely to what they call harrisi,

and are supposed to be as south as Panama, according to their ppt. https://ebird.org/checklist/S93955615 https://ebird.org/checklist/S79099153, from Lima, Piura, and I guess a

thorough search will find more.”

Additional

comments by Claramunt:

[in response to Clark’s points]: "My point is

that there seems to be a discrepancy between adult plumages and juvenile plumages

in SA birds E of the Andes: the adult plumage matches harrisi, the

juvenile plumage matches unicinctus. Which one is correct? We don't

know. We can't just assume that the juvenile plumage is correct in indicating

affinities here. Maybe both are "correct" and these birds share

traits and genes with both North American and eastern S American birds."