Proposal

(792.2) to South American Classification Committee

Establish English names for Thamnistes species (3)

The two previous attempts to establish English names

have produced stalemates that seem intractable within our informal English

names subcommittee, and from comments below, it’s pretty clear that a 2/3

majority is not achievable. Therefore,

to avoid further delay in implementing this split, I am going to try something

new, something that is guaranteed to produce a majority vote for one of the

three options (if everyone asked to vote does so). I am expanding the voting considerably to

include a number of individuals who have shown an interest in SACC English

names through their contributions, either proposals or comments, on previous

English name proposals, and their votes will be tallied as the come in for the

three leading options.

Option 1: compound names:

Thamnistes anabatinus Northern Russet-Antshrike

Thamnistes rufescens Southern Russet Antshrike

Option 2: retaining the traditional parental name

for one of the daughters and coining a new one for one of the daughters:

Thamnistes anabatinus Russet Antshrike

Thamnistes rufescens Rufescent Antshrike

Option 3: new names for both daughters by

resurrecting an old one and coining a new one:

Thamnistes anabatinus Tawny Antshrike

Thamnistes rufescens Rufescent Antshrike

The pros and cons of each option are tediously

explicated in the two previous iterations – see below. I see no point in restating these, but if you

have something new to add, please do.

Note that Thamnistes anabatinus is really a

NACC bird, so in the end, I think they should have the say over that name.

Van Remsen, July 2020

Note from Remsen (Nov. 2020): the majority

of respondents favored Option 2, so I am going to consider Option 2 as the one

SACC will adopt.

SACC:

Hilty: Option 2

Jaramillo: Option 2

Remsen: Option 3

Schulenberg: Option 2

Stiles: Option 3

Stotz:

Whitney: Option 2

Zimmer: Option 3

Others:

Don Roberson: Option 1 (Despite my generalized dislike for

compound names, I vote for Option One, with hyphens. I generally prefer English names that are

short and memorable. The “Russet Antshrike” part is already memorable, but

learning two new names of similar colors will surely be confusing. I’m also

swayed by the potential split, and rather like Napo Russet-Antshrike as a

potential third name, as suggested by someone below.)

Rich Hoyer: Option 3 (Both getting new names and no clunky

hyphenated group names. The knowledge that there was once a Russet Antshrike

will be quaint trivia a few decades from now.”)

Dan Lane: Option 3 (My first choice of English names for the

two Thamnistes following the split would be:

T. anabatinus: Russet Antshrike

T. rufescens: Rufescent Antshrike

In agreement with the assessments of

others, the strongly unbalanced distributional areas and the fact that records

of T. anabatinus far outweigh those of T. rufescens combine to

make it clear that retaining the name "Russet" for the anabatinus

group is the best course of action for now, with the possibility that an

additional split may require another change in the future. In any event, I am

not a fan of "Northern and Southern Russet-Antshrikes" because I find

such names uninteresting, cumbersome, and most importantly, remove the species

from being found under "Antshrike" in the indices of reference works,

which is no small consideration!)

Craig Caldwell: Option 2 (“Gill and Donsker (IOC) and Clements/eBird

have used them since they recognized the split, and I'm all for the benefits to

my fellow amateurs of having all the major taxonomic schemes use the same

names.”)

Gary Rosenberg: Option 1 (“1) I agree with others who have argued

that there is just too much of an established history for the common name

“Russet” - even if it is not the best or most accurate in matching colors. 2) I

am not the biggest fan either of making common names long, hyphenated names,

but using “Northern” and “Southern” will be self-explanatory and easy for

birders to incorporate into their thinking when it comes to common names -

especially in this case where there are natural northern and southern

populations . Creating two new names will be unnecessarily confusing. I can

attest that birders on tours HATE when names are changed that make things more

confusing”.)

Peter Kaestner: Option 2 (“Keeps the original name for the species

that is overwhelmingly observed (thanks Josh) and the newly-coined name

reflects the Latin moniker. I agree with

Alvaro that we don’t need to blindly follow the rule of not maintaining the

original name for a daughter species.”)

Steve Howell: Option 2 (“My choices

would be as follows, or the other way around (!) as there is no clear “winner”

here:

1. Russet

and Rufescent (if it looks like only 2 splits

will ever happen), and as done I think by IOC following the

recommendations in the Isler & Whitney paper. (But I really like Tawny,

it’s just a matter of “if not broken, don’t fix it” an adage of which Eisenmann

was utterly unfamiliar…) In cases with 2 allopatric non-migratory species, I

think keeping one name is OK (a la Red-eyed Vireos).

Thus, option 1a is also fine. Tawny

and Rufescent. BUT… if it looks like more

splits, Western, Eastern, Peruvian, or whatever could happen, then yes

to:

2. Northern

Russet Antshrike, Southern Russet Antshrike; remembering Russet Antshrike is

easier than new names (yes, new birders will never know the old names, but if

they are called “Northern” or whatever it will teach people there are related

species, since I doubt the present generation of eTards even looks at something

known as a genus”).

David Donsker: Option 2 (“For the reasons already stated by those who also favor this option”.)

Mort Isler: Option 2 (“for reasons that

others have stated, but I also agree with the reasoning for option 3, and it

was a tough choice. Option 1 is undesirable, particularly given evidence that

additional species splits may result from more information on the cis-Andean

populations”)

Mark Pearman: Option 2 (“… on the grounds of

maintaining the name Russet Antshrike for the well-known and endearing anabatinus, while I think

Rufescent is a reasonable name for rufescens reflecting the specific

name and plumage.”)

Marshall

Iliff: Option 2:

(I don't feel incredibly strongly about these, but I

would also vote for option 2:

Thamnistes

anabatinus Russet Antshrike

Thamnistes

rufescens Rufescent Antshrike

For

option 1, while I agree with what Gary writes, I think Northern Russet

Antshrike and Southern Russet Antshrike get pretty unwieldy.

In

many cases I would endorsed option 3, since you know I am a strong proponent of

new names for daughter species when a split occurs. I feel like I should lay

out my rationale and if my reasoning below makes sense and if SACC continues to

address English names, it may be worth considering if this might be an expanded

exception.

To

me it boils down to the probability that retention of a daughter name will

generate confusion and (in my world at eBird) resultant data entry error.

Giving

separate names for daughter taxa causes a bit of early confusion and then

birders, fields guides etc. adapt. Canyon and California Towhees were far

better than arbitrarily retaining Brown Towhee for one of the parents. This is

especially important when multiple taxa are split out, so retiring the names

Paltry Tyrannulet and Blue-crowned Motmot and reserving them for the entire

species complex is ideal. It has been great to see this philosophy increasingly

engrained in comments by SACC and NACC. It has been good also to see this

formally enshrined for NACC and (maybe?) SACC: https://www.museum.lsu.edu/~Remsen/SACCprop857.htm

However,

we all recognize that this need not be taken to a ridiculous extreme. When the

Andaman population of Barn Owl is split out as Andaman Masked-Owl Tyto deroepstorffi https://ebird.org/species/barowl5, we need not require that Barn Owl change its name.

Nor did recognition of Hispaniolan Crossbill really mean that White-winged

Crossbill needed a name change.

The

current SACC proposal gets at this -- https://www.museum.lsu.edu/~Remsen/SACCprop857.htm and states:

1.1.a.

Relative range size. In many cases, relative range size is an excellent proxy

for the differential effect of a name change. When one or more new daughter

species are essentially peripheral isolates or have similarly small ranges

compared to the other daughter species, then the parental name is often retained

for the widespread, familiar daughter species to maintain stability. For

example, the English name Red-winged Blackbird was retained for the widespread

species Agelaius phoeniceus when the Cuban subspecies A. phoeniceus assimilis

was elevated to species rank, and a novel English name (Red-shouldered

Blackbird) was adopted only for the daughter species A. assimilis.

1.1.b.

Differential usage. In some cases, a name is much more associated with one

daughter species regardless of relative range size. For example, the name

Clapper Rail has been consistently associated with birds of the eastern US and

Caribbean for over a century, whereas populations in South America and in the

western US and Mexico were known by various other names before being grouped

under the name Clapper Rail. In this case, despite the extensive range of the

South American daughter species (Rallus longirostris), the name Clapper Rail

was retained for eastern North American daughter species (R. crepitans) when

the species was split into three, with Mangrove Rail applied to the daughter in

South America and Ridgway's Rail to that in the southwestern US and adjacent

Mexico (R. obsoletus).

My

reason for being willing to retain Russet Antshrike for one daughter here is

that in terms of English usage, the distribution is highly asymmetrical -- so

it is sort of a hybrid of 1.1a and 1.1b above. I would argue that there is much

more engrained English usage in the multiple English language field guides

(Mexico, Central America, Costa Rica, Panama, Colombia, Ecuador) within the

range of Thamnistes anabatinus than

for Thamnistes rufescens (Peru,

Bolivia). I also would say that the English speakers who might use English

names in Peru and Bolivia--primarily tour participants and savvy independent

travelers--are more well-versed in how taxonomy and nomenclature are shuffling

around and also more likely to use the scientific name (which, of course, is

even worse, since retention of a parental name is required!). So in the end, I

see very little problem in retaining Russet for the northern birds in a zone

where English names are more widely used and in more contexts (at least

measured by number of field guides). To me this is akin to the split of Gray

Hawk and Gray-lined Hawk, except that the recognition of the southern taxon

here is one with an even more restricted southern range.

Within

eBird, we see lots of data quality errors when people are persistently confused

by the English names. If the southern T.

rufescens were to get the name

Russet Antshrike, we'd end up with a data quality disaster as dozens/hundreds

of people would search for Russet Antshrike in Mexico, Costa Rica, Panama etc.

and enter it, not knowing that it referred to a species found only in Peru and

Bolivia. So for me, if observers are unaware of the split but correctly

identify it in their field guide, they are vastly more highly likely to land on

the right name if we retain Russet. We can actually measure this: eBird has

7395 records of Russet https://ebird.org/species/rusant1 compared to only 116 of Rufescent https://ebird.org/species/rufant12. If we removed Spanish speakers or highly advanced

users, such as members of SACC, I expect this ratio would be even more biased.

In my mind, the name change for daughter taxa is most important when the

correct English name will result in lots of errors, which would have been the

case if Hispaniola Crossbill had instead used White-winged Crossbill. To

illustrate continuing real-world problems, it was a mistake (in my view) to

retain Common Snipe for one of the two taxa in the New World-Old World split of

Gallinago gallinago and also to retain Audubon's Shearwater for the tiny

Caribbean isolate that was left after Persian, Barolo, Boyd's, Galapagos,

Tropical, and Bannerman's all got split out and given new English names.

The

original proposal https://www.museum.lsu.edu/~Remsen/SACCprop792.htm also points out that T. anabatinus sensu

stricto has a larger distribution, roughly twice the latitudinal distribution,

and contains 6 of the 7 named taxa.

So

I vote option 2:

Thamnistes anabatinus Russet Antshrike

Thamnistes rufescens Rufescent Antshrike

_____________________________________________________________________

Proposal

(792.1) to South American Classification Committee

Establish English names for Thamnistes species (2)

To begin with, the genus

Thamnistes has long

been treated as monospecific, and the name Russet Antshrike has been in

continuous universal use for ca. 70 years. SACC’s policy of retaining the

original name only for the broadly circumscribed species and coining or resurrecting

different names for the newly spit daughter species sometimes causes problems,

as in this case: the name Russet Antshrike is just too well established to

sweep under the rug. So, the alternative here would be to use it as a

genus-level name for Thamnistes

(with or without a hyphen) and add appropriate modifiers to its

newly-split progeny. Hence, two alternatives are as follows:

1. Use geography; the distribution of the taxa is pretty nearly

linear, which facilitates this. The northernmost populations (from Mexico to NW

Colombia) could be called Northern Russet-Antshrike. Newly split

rufescens could be

called either Southern or Peruvian Russet-Antshrike (virtually its entire range

falls within Peru). So, the options I propose are:

a. Northern and Peruvian Russet-Antshrikes, or

b. Northern and Southern Russet-Antshrikes

These alternatives leave open the possibility for adding similar

names for aequatorialis

and gularis

should these also be split. For the former, I’d suggest Ecuadorian

– although it also occurs widely in Colombia, this ties in with the Latin name,

possibly an advantage; an alternative could be Napo Russet-Antshrike. For

gularis, Perijá Russet-Antshrike would fit its apparently restricted

distribution.

2. Use color names. Thus, the northern group would become Tawny

Russet-Antshrike, rufescens

would become Rufescent Russet-Antshrike. This is clear enough,

although the juxtaposition of two different color names in the same English

names could well be a bit confusing. However, the situation becomes worse if

aequatorialis or

gularis also were

to be split. Here, the much-abhorred colorimetric hair-splitting would be

necessary in coining the required new names.

I therefore recommend alternative

1, and lean towards 1a with an eye to future contingencies.

Gary Stiles,

October 2018

Comments from Remsen: “NO on all. I don’t

like the compound names, and there are ways to avoid them, as in 790.0. Also, retention of the parental name “Russet”

for a daughter species is not justified, in my opinion. The northern taxon may be more familiar to

many, but rufescens has a large range, and thus we do not have, in my

opinion, sufficient asymmetry to justify retaining parental Russet in a

daughter name.”

Comments

from Schulenberg:

“NO. I don't like long compound names. And I don't

see anything wrong with Rufescent Antshrike for rufescens, and with retaining Russet Antshrike for anabatinus sensu stricto. The disparity

in the geographic ranges of the two is great enough that I'm not worried about

confusion after rufescens is carved

out - especially since, as noted previously, the form that is seen most often

anyway is the one that would retain the familiar name.”

Comments from Jaramillo: “NO. The proposal notes: ‘the name Russet Antshrike

is just too well established to sweep under the rug.’ I agree, so let’s keep

Russet Antshrike for anabatinus, and

create Rufescent Antshrike for rufescens.

Although it is great or a goal to avoid retaining a group name for one of the

daughter species, I don’t think it should be a rule. Sure, there is some

certain amount of confusion it causes. But on the other hand, we seem to deal

with it without much problem when dealing with scientific names. I mean Thamnistes

anabatinus means

something different before the split as opposed to after the split. Some of the

confusion will be temporary, but the benefit of keeping a well-established name

such as Russet Antshrike has great value. Avoiding a compound name also has

great value.”

Proposal

(792.0) to South American Classification Committee

Establish English names for Thamnistes species (1)

With passage of SACC proposal 758, we now recognize two

species of Thamnistes, based on Isler

and Whitney (2017). We haven’t

implemented the proposal because we need to establish English names for the two

newly delimited species.

Isler and Whitney (2017) recommended

retaining long-standing Russet Antshrike for T. anabatinus and Rufescent Antshrike for T. rufescens. The problem

with that is that our guidelines and those of NACC recommend new names for both

daughter species because retaining the parental name for one the daughters

creates obvious confusion as to what the shared daughter-parental name refers

to (in this case Russet Antshrike). This

is only a guideline, however, not a rule because in many such cases, one or

more of the daughters are peripheral isolates for which changing an established

name for the remainder of the widely occurring species creates unnecessary

instability. An extreme example within

the SACC area would be Vireo

gracilirostris, formerly considered a subspecies of Red-eyed Vireo. Rather than changing names to something like

“Common Red-eyed Vireo” and “Noronha Red-eyed Vireo”, the sensible pre-SACC

decision was to retain traditional Red-eyed for the widespread daughter and

call gracilirostris “Noronha

Vireo”. But what if the distributions

are not that asymmetric, as in the two Thamnistes?

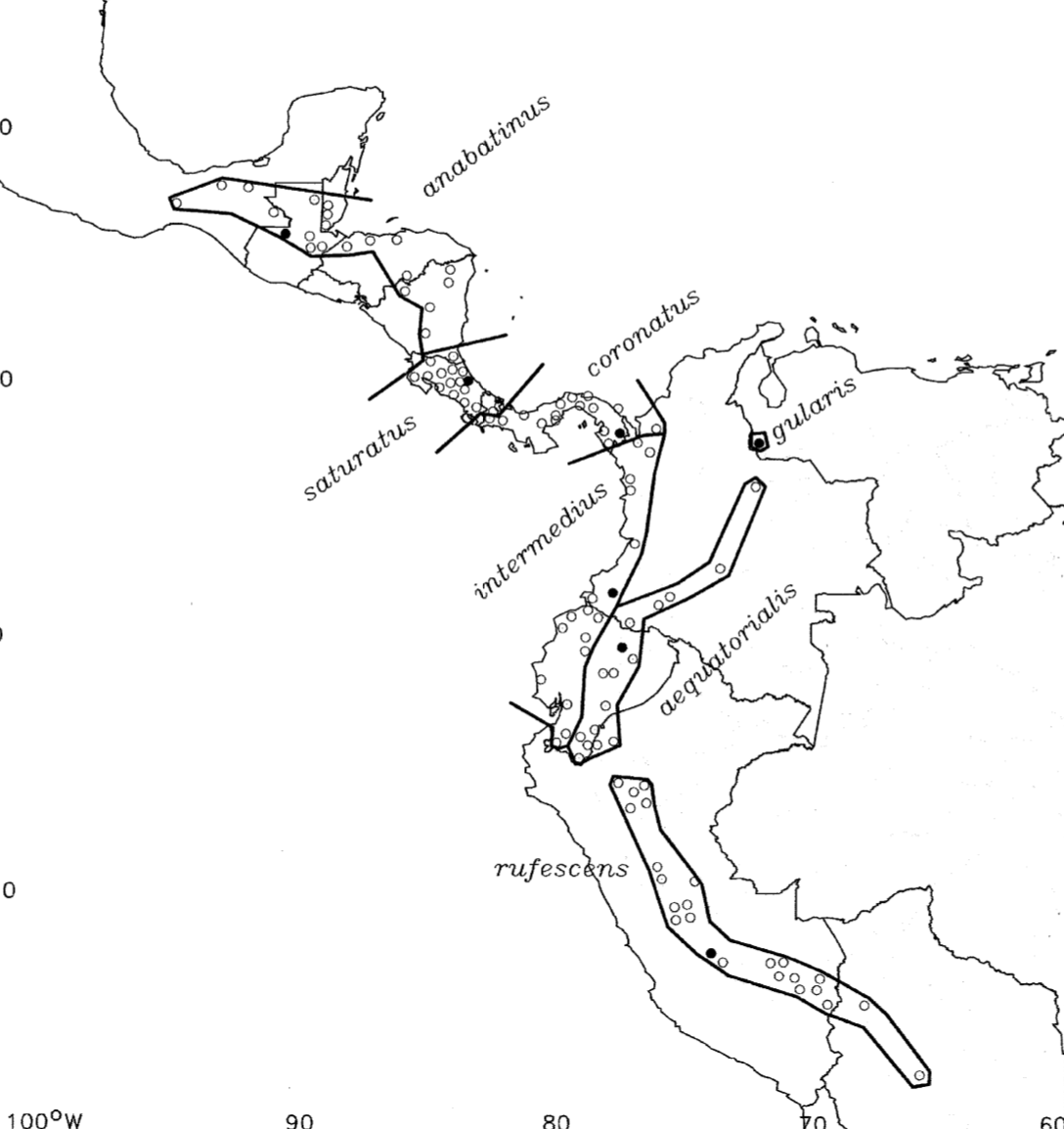

Below is the distribution map from

Isler and Whitney (2017):

As can

be seen, T. anabatinus sensu stricto

has a larger distribution, roughly twice the latitudinal distribution, and

contains 6 of the 7 named taxa. So, the

distributions are asymmetric but not highly so.

However, taxonomic asymmetry is such that retaining Russet for T. anabatinus would mean that the

English names would remain stable for 6 of 7 taxa. However, whether cis-Andean aequatorialis belongs with anabatinus or merits species rank on its

own is nuclear; from Isler and Whitney:

“The status of aequatorialis is less clear. Maintenance as a subspecies is recommended on the grounds

that although elevating aequatorialis to species status might result from the acquisition and analysis of

additional data, later elevation is preferable to elevating it now and then

finding that additional data demands reducing it back to subspecies status.”

Also,

gularis was not sampled; presumably

it is more closely related to adjacent aequatorialis

than anything else. Thus, if

additional data show that aequatorialis (plus

gularis?) merit species rank, then the

asymmetry among the species disappears.

If we decide to go with new names for

both daughters, one option is to generate compound names, e.g. Something

Russet-Antshrike and Rufescent Russet-Antshrike. Compound names are generally unpopular,

however.

A third possibility would be to provide

a new name for T. anabatinus sensu

stricto. In my comments in the

original proposal, I suggested “Tawny Antshrike” as a possibility. This is actually the English name used by

Ridgway (1911) for nominate anabatinus

(Mexico through Nicaragua) and thus was “the” name used in English literature

from Mexico and n. Central America from Ridgway’s time through at least 1955,

when Eisenmann selected “Russet Antshrike” (used by Ridgway for T. a. saturatus) as the name for the

species as a whole. I’m not sure why he

did this except that saturatus occurs

in w. Panama, his country of interest.

In contrast, “Tawny” applied to the nominate subspecies, to the larger

part of the composite species range, and to a greater proportion of the plumage

area. To me, just looking at the

specimens photos (proposal 758) “tawny” seems at

least as appropriate if not better than “russet” for the species. Further, “Tawny” is especially appropriate as

a foil to “Rufescent”, which is distinctly “redder” overall.

Here is a photo of all our specimens,

“Tawny” on left (except for aequatorialis),

“Rufescent” on right:

Therefore, I propose “Tawny Antshrike”

for T. anabatinus. It avoids the problem of having a daughter

species carry the parental name, avoids a compound name, is arguably more

appropriate than Russet, and as a bonus revives a good name that was in use for

40 years and should have been the name chosen for the species if Eisenmann had

not had a Panama bias. A YES vote would

be for Tawny and Rufescent as the names for the two daughter species. A NO would be for something else, presumably

Russet and Rufescent, the choice of many of you in the informal discussions in

proposal 758.

Be sure to see others’ comments on

English names in proposal 758, especially Bret’s (in

defense of Russet) and Gary’s.

References:

EISENMANN, E. 1955. The

species of Middle American birds. Transactions Linnean Society New York 7: 1–128.

ISLER, M. L., and B. M.

WHITNEY. 2017. Species limits in the genus Thamnistes

(Aves: Passeriformes: Thamnophilidae): an evaluation based on vocalizations.

Zootaxa 4291 (1): 192–200.

RIDGWAY, R. 1911. The birds of North and Middle

America. Bulletin U.S. National Museum,

no. 50, pt. 5.

Van Remsen, June 2018

Comments

from Stiles:

“NO. For this

proposal, I suspect that "Tawny Antshrike" may upset too many apple

carts. Russet Antshrike has been in

continuous use since the 1950s in everything from technical literature to bird

guides to birders' notes from Mexico to Argentina. Although I rather like Tawny, I think that

Russet just has too much momentum to change. Given that the spit of rufescens from anabatinus

will be implemented by relatively few countries, I'd prefer to leave the rest

as Russet Antshrikes.”

Comments from Steve Hilty:

“Herewith some comments on the naming process, with Thamnistes as an example. What follows may strike some as lacking

innovation, but names should be easy to recall. Coining a unique new name for

every new taxon split and obsessively avoiding compound names does not produce

a set of names that are easy to recall and it is counterproductive. The

following sets out my argument.

“Yes, I agree (with Bret in SACC 758). “Why in the world would you want

to change a long established name like Russet Antshrike?” I also concur (with

Gary) that it is unnecessary to adhere to restrictive rules regarding changing

English names each time a taxonomic change occurs, especially when there are so

many parent-daughter splits that need attention. The SACC process of choosing English

names is somewhat cumbersome and often not particularly helpful to the few of

us involved with SACC who actually use English names on a regular basis.

“Here is one of the problems. I personally cannot retain fifteen or

twenty thousand (or more) unique and

often new English names in my head—and there will be more on the way every

week for the foreseeable future and beyond. I can, however, retain some small

fraction of that number and use them effectively with birding clients. In this

regard it helps considerably if, after a split or multiple splits occur, the

“mother” name is retained and simply modified with a relatively predictable

modifier such as Eastern, Western, Northern and so forth. This might or might

not involve a hyphen.

“So, is anybody actually doing this? Beyond the world of SACC, it may be

instructive to see what others on the planet are doing. All of you likely

already know that Lynx Edicions is embarking on an ambitious project to produce

compact bird guides for many or most countries around the world—and you can be

sure that sooner, rather than later, most South American countries will be

included. Lynx is highly efficient and excels at compiling and disseminating

vast amounts of information electronically and via hard copy, and they do it

quickly and accurately. They incorporate new genetic findings into their

taxonomy as it appears, but supporting genetic data tends to appear in fits and

starts and often glacially slow—and will certainly continue well beyond the

lifetimes of all of us at SACC and Lynx. Clearly Lynx clearly is not going to

wait that long.

“To this end Lynx utilizes a numerical taxonomy system, often maligned,

but in the end reaching conclusions not much different, and far more quickly

than others including SACC. What they don’t do is adhere to the almost

untenable goal of attempting to coin a new

unique English name for every split.

Whether one quibbles with numerical taxonomy or not, names need to be invented

on a timely basis with the goal of being

useful. Eugene Eisenmann faced this when he help Meyer de Schauensee

standardize South American bird names for the latter’s Red book (1966) and Blue

book (1970). Prior to that point names were all over the map. But Eisenmann

fell into the trap of trying to make as many names as possible descriptive by

using colors. It seems like a good idea—until you actually had to use these

confusing names—and now with hundreds of new taxa needing names every year it

is only getting more confusing. e.g. Rufous-fronted, Rufous-crowned, Rufous

naped, Rufous-cheeked, . . . and then start over with gray, or buff, or tawny,

or ochre or some other obscure color. We end up with 50 shades of gray (no pun

intended) on all kinds of birds, some related, some not, or 50 shades of rufous

and so on. And SACC is doing this all over again—Russet versus Rufescent versus

Tawny antshrike?

“I checked the species account on Lynx’s HBW Alive website for Russet

Antshrike. It is already split, although not exactly as SACC is doing. In fact,

when SACC splits out the aequatorialis group,

as they surely will in due time, SACC will have three species of Russet

Antshrikes (anabatinus, aequatorialis and rufescens),

whereas HBW has, at present at least, only two (anabatinus and aequatorialis),

in both cases based largely on numerical taxonomy. But—the key difference is in

the names. HBW simply names them Western Russet Antshrike (anabatinus) and Eastern Russet Antshrike (aequatorialis). If southern rufescens

gets split out (and I’m betting HBW will pick that up soon enough), then it

may well become, logically enough, Southern Russet Antshrike. It is all quick,

simple and very easy to remember. SACC could simply call rufescens the Southern Russet Antshrike. Leave the other name

alone. Then, if later on SACC splits out aequatorialis,

just add Western and Eastern to the

cis- and trans- forms and you’re done. No committee meetings necessary.

“Now, I also scanned through some of HBW Alive’s species accounts and

they have done this same thing over and over with new splits. Nearly always retaining the “mother” name and just

adding a modifier—most often a compass direction (Eastern, Western, Northern,

Southern, Central), occasionally a geographical region (Amazonian, Guianan,

Andean, Sierra Nevada, Rio Negro, Napo, Choco), country name (Costa Rican,

Colombian), a size difference (Greater, Lesser) and so on, but only very

infrequently a new color (Cerise, Violet, or something attention-getting). Yes,

the name might be a little longer. But why do we really care if the name is a

little longer? We should care more about if it is easily modified in the future

(no need for more round-table discussions), minimally confusing and especially

if it is easy to recall.

“For those of use that actually use English names in our professions

(that leaves out most SACC members), HBW’s naming system (if that is what it

is) greatly simplifies the process of recalling names—in other words if you can

remember the “mother” name you will also have a good idea of how six or eight

splits of that “mother” species filter out. SACC did this with the

warbling-antbird group and it worked well. SACC should employ this simplified

system more often. It is much easier to organize and recall the hundreds and

hundreds of names (soon to be thousands I fear) and the little bits of

taxonomic flotsam in the system if they are somehow connected, but also there

is another important reason why SACC should move in this direction and it

involves working at an international level with the goal of a single unified

English language name system.

“Lynx Edicions method of dealing with new names for birds is heavily

biased toward using a relatively small number of categories mentioned above

(especially compass directions) but the system makes recalling names easy. And,

like it or now, they are about to flood the planet with high quality bird

identification guides using their

illustrations and their names. In fact, they are already well on their way

with the completion of their remarkable handbook series, more recent checklist,

web sites and other works in process. SACC is producing, at great labor, a

unique and laudable, peer-reviewed system of taxonomy for South American birds,

but the burden of trying to coin new and

unique English names, by throwing away perfectly usable “mother” names every

time there is a taxonomic split is slow and cumbersome and counterproductive

for users of these names. In the end, SACC’s English names may not see much

daylight if major publishers of bird books don’t use them.”

Comments from Jaramillo: “NO. Although I hate long compound names, I do think that in this

case, the name "Russet Antshrike" should survive in some form.

Interestingly, the part that pops out from your specimen photos are the pale

bellies vs rufous bellies. But Pale-bellied Russet Antshrike may be too much

for some to swallow.

“Also, regarding Steve

Hilty's thoughts on recollection of names, I get it, it can be a bear to

remember new names. But then again, not insurmountable. But I would look longer

term. The only people who will have to recollect what is what are those in the

field today. The younger birders will just know the new name and have no idea

that it was called something else before. So, names that are just good,

descriptive, memorable, or what have you are best. Using northern or southern,

also assumes you know the entire avifauna and realize there is one to your

north or south that is related.”

Comments

from Stotz:

“YES. I think Tawny is a good, solid

name for the northern species. I prefer

it to a compound name version or keeping Russet for the northern birds. Part of this comes from the fact that I know Thamnistes from the fringe of Amazonia,

so Russet Antshrike is associated with those birds rather than the Central

American birds.”

Additional

comment from Remsen:

“Like Doug, “Russet Antshrike” has always referred to rufescens, and I for many years I was only barely aware that the

species also occurred as a pale-bellied ‘deviant’ form in Middle America. So, just as with “Slaty Thrush”, primary

association depends on one’s background.”

Comments

from Josh Beck:

“I think the argument for stability

should receive more weight in this case. My personal impression is that Russet

Antshrike (sensu lato) is far more commonly observed in Middle America and west

of the Andes than east of the Andes, so I took a quick look at raw data output

from eBird for the broader T anabatinus.

eBird has a bit over 6000 records of the species. There are no records of gularis, 128 records for rufescens, 247 records for aequatorialis, and 5841 records for the

trans-Andean forms (anabatinus

following this split). I can also count 15+ currently widely used field guides

that use the common name Russet Antshrike from Mexico to Ecuador. I also

personally don't see Tawny Antshrike as a particularly better or more memorable

name, just different, but will avoid the 50 shades of gray argument again.

Essentially, there are far more birders and national/regional guides that use

Russet Antshrike to refer to trans-Andean birds than cis-Andean and as a result

I am much in favor of one of the two options that retains Russet Antshrike as

an English name: A) keeping Russet Antshrike for anabatinus and giving rufescens

a unique name (Rufescent or other), or B) using compound names (Western

or Northern vs Southern Russet-Antshrike) if it is viewed as likely that there

will be further splits in the future.”

Comments from Zimmer:

“NO. I’m

really on the fence on this one. I would

start by saying that I think Josh Beck’s analysis is spot-on in that the name “Russet

Antshrike” is far more familiar and more often in use (in literature, eBird,

trip lists, etc.) with respect to the trans-Andean populations, particularly

from Middle America, so, it would be more painful to lose that name as applied

to those populations. However, as Van

points out, the modifier “Russet” is not especially descriptive of the anabatinus group, and his suggestion of

“Tawny” and “Rufescent” is actually more appropriate, even though I generally

have an aversion to hair-splitting color-based names for similar species in the

same genus/family. Although “Tawny” and

“Rufescent” are more descriptive, and attractively short and simple, the

downside is that adoption of those names puts us in a box if either aequatorialis or gularis (or both) get elevated to species-level at some point,

because coming up with English names for 1-2 additional taxa would put us back

into hair-splitting subtle color differences again. The same can be said for what would happen if

we retain “Russet” for 6 of the 7 taxa and coin “Rufescent” for rufescens, only to find out later that

we need one or more new English names for aequatorialis/gularis. For this reason, I think that using a

hyphenated group name of

“Russet-Antshrike” is the best way to go, because: A) it retains the history of “Russet

Antshrike”; B) it’s more informative; and C) it’s more flexible in allowing for

future splits without getting into confusing, color-based names. I realize that these longer, hyphenated names

are unpalatable to some of us, but in this case, I would join with Steve and

Bret in saying that I think it is the best of an imperfect bunch of choices.”

Additional comments from Remsen in

response to Hilty’s comments:

“Good points, Steve, but the landscape has changed with the partnership of

Cornell Lab of Ornithology (and thus Clements) with HBW/Lynx, so whether that

also means that Lynx publications with follow BLI names is uncertain,

especially those not yet published. Tom,

what do you know?”